Tragopans and Tribals: A Naga Transformation?

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 25

No. 10,

October 2005

by Ashish Kothari and Neema Pathak

Nestled within one of the most beautiful mountain landscapes in Kohima district, is a settlement of Angami tribals. This region was till recently subject to intense hunting pressure. In the mid-1990s, a local resident, Tsilie Sakhrie and a forest officer by the name of T. Angami (originally from the village), came up with the idea of protecting some forests that still contained significant wildlife. In particular, they hoped to protect the threatened Blyth’s Tragopan Tragopan blythii.

After a series of consultations within the complex social structure of the village, the Village Council in 1998 declared 20 sq. km. of forest and grassland as the Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary. Rules were formulated to ban hunting here and across Khonoma’s 135 sq. km. area and to stop all resource use in the sanctuary area. The idea was to use the buffer area for community needs. A Trust was set up and over the past few years, with help from Equations, an NGO, and others, a tourism master plan was written to earn income without causing ecological damage. This also resulted in a village clean up that ushered in better sanitation and hygiene. A proposal is now being mooted to extend the sanctuary area and discussions are being held with neighbouring villages to protect the entire Dzukou Valley (banner image above). This would conserve 200 sq. km. of a very unique habitat, along with several endemic and threatened species.

Village after village, such as Kikruma, has begun to demarcate no-hunting and no-deforestation zones indicating that local people are willing to demonstrate their will to protect nature. Photo: Ashish Kothari.

In 2004, the Chakhasang Public Organisation (CPO) comprising 80 villages in the Phek district of Nagaland, resolved to prevent indiscriminate forest fires and to ban hunting seasonally in their respective areas. Prior to this, 23 Chakhasang tribal villages had declared part of their lands as strictly protected for wildlife. In the nearby Kohima district, many Angami and Rengma tribal villages (such as Khonoma, Tuophema and Sendenui) instituted similar prohibitions. In Chishiling village in the Zonheboto district, residents banned hunting in a designated forest area in 1995, and stopped all use of explosives in the Tizu river to reverse fish declines. In the same district, the Ghosu Bird Reserve was among the first Community Protected Areas to be declared.

These are but a few examples of a quiet and remarkable revolution taking place in this usually forgotten corner of India. Most of us believe that in the northeast everything that flies, walks, or crawls is hunted. This reputation is not entirely undeserved. Nagas (and their neighbours) will readily agree that with the introduction of firearms, hunting has been indiscriminate and widespread. Many species of hornbills, primates, cats, among others, have been driven to local extinction or near-extinction by hunting combined with habitat destruction.

In this context, community conservation initiatives in Nagaland are of tremendous significance since 88 per cent of Nagaland’s forests belong to communities or individuals, rather than the government as in other parts of mainland India.

Luzophuhu was the first village in the Phek district to initiate conservation measures when young villagers chose to conserve a five square kilometre forested patch to protect a key water source. Photo: Ashish Kothari.

Village Wildlife Sanctuaries

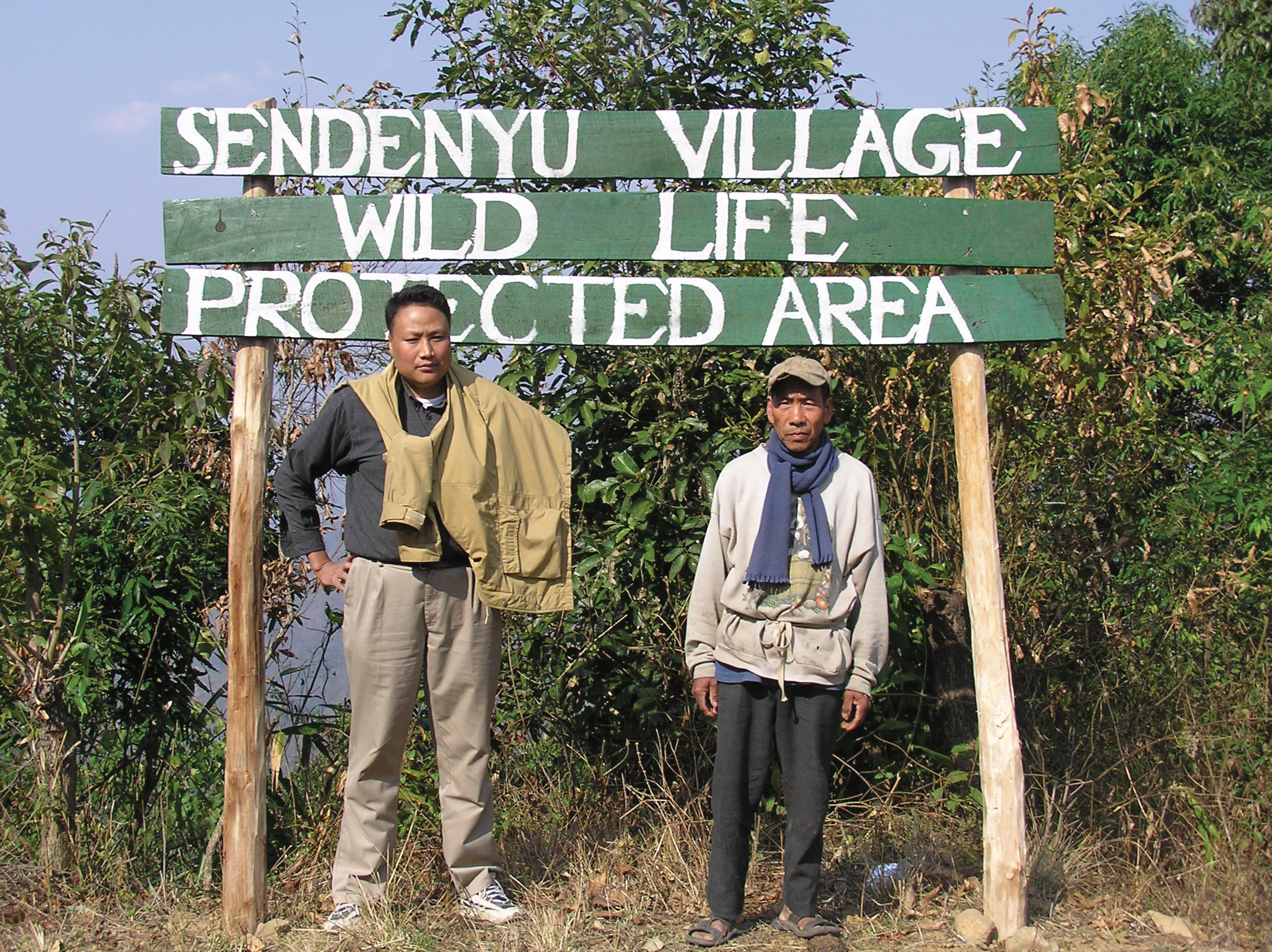

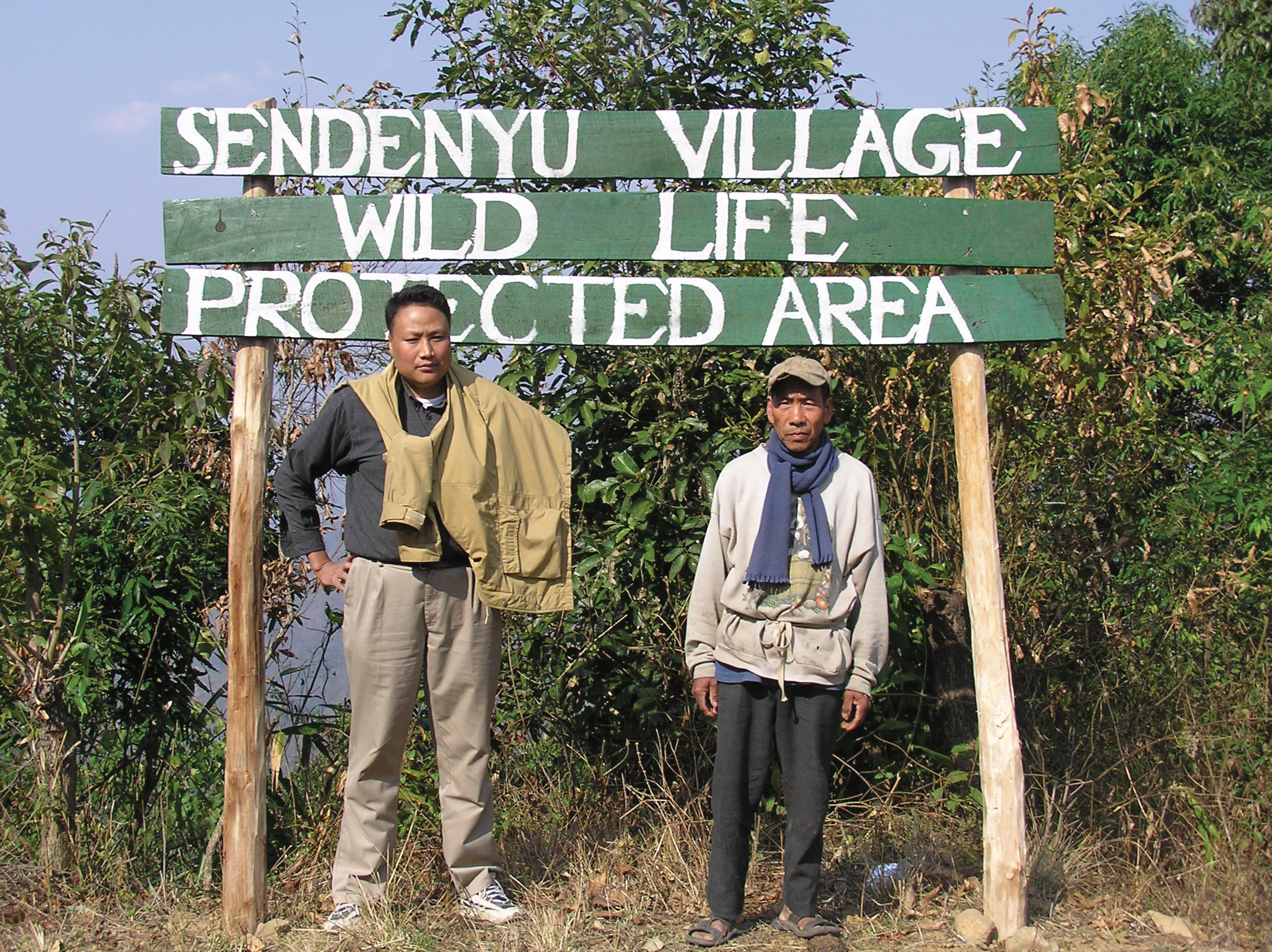

As we moved beyond Khonoma, we heard still more fascinating stories. In Sendenui village, every family owns a gun and the village prides itself on its hunting prowess. Some young villagers, however, having returned from studies outside the state, initiated discussions with their elders to leave some inviolate spaces for animals to breed. The elders wholeheartedly supported the idea. Homa Seb, one of the Gaon Buras told us he had vivid memories of large flocks of hornbills and that the elders pined for the days when monkeys and other animals could be easily seen.

The village council decided to set aside an area for wildlife and began to negotiate boundaries with individual land owners. G. Thong, a young government officer in Kohima who had initiated the protection move explained: “Convincing the land owners was not easy, but if people were not happy, conservation would have no support in the village.” Help was therefore sought from the Forest Department and 30 LPG connections were handed over to those whose land was ‘taken over’. It was also decided that they would be the primary beneficiaries of any other government schemes in the future.

Compensation was also paid by villagers to the church to move its cattle shed outside the designated sanctuary. The village issued its own ‘wildlife protection act’, with rules and regulations for the management of the sanctuary. The authority for this was drawn from the state’s unique Village Council Act. The villagers estimate the Protected Area to be 10 sq. km.

Luzophuhu, a Chakhasang tribal settlement, was the first village in Phek district to initiate explicit conservation measures. In 1983, the Luzophuhu Students’ Union (LSU) decided to conserve a five square kilometre forested patch above the village to protect a key water source. The area had been subjected to jhum (shifting) cultivation and only if all land owners agreed would the initiative be possible. Hunting was allowed, as also firewood collection, and the occasional cutting of trees. In 1990, the LSU resolved to declare another patch of forest below the main village, between the settlement and paddy fields, as a wildlife reserve. Here too, individuals were persuaded to donate their lands. Hunting was strictly prohibited in 250 ha.

Phek village has now declared its own wildlife reserve adjacent to Luzophuhu’s forests to form a contiguous habitat (though Phek’s protection is not quite as strong). Luzophuhu also declared a two-kilometre stretch of river below the village as a no-fishing zone.

An old hunter’s house in Luzophuhu. Traditionally, renowned hunters display their trophies with pride in their homes. Photo: Ashish Kothari.

A Growing Movement

Everywhere we travelled through dense forests, we heard of more such community conservation initiatives. Kikruma village is regenerating and protecting 70 ha. of land. Several villages around Runguzu protect the famous Zanibu range that extends across thousands of hectares of forest. Six villages led by Chizami village are reviving traditional protection over a few hundred hectares and all along the road from Kohima to Phek, we saw signs put up by village youth associations, warning that the area was under strict protection. Wildlife expert Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhary, who has travelled extensively in the area, says that these signages serve to deter outsiders as well. Villages have different punishments for violations, ranging from simple fines to complex retributions. In Sendenui, for instance, killing sambar, invites a relatively higher fine as the village believes the deer is more seriously threatened.

Every initiative has its own management model, rules and regulations. Some are declared on community-owned lands, others on lands donated by individuals, and still others on lands purchased by the village council. The conservation movement is spreading fast in Nagaland. An indication of this is a CPO resolution, spearheaded by CPO leader Pusazo Luruoto, to extend it to the whole of the Chakhasang tribe.

Unfortunately, there is no systematic study of fauna at any of these sites, and virtually no information on smaller animals or rare, endemic, and threatened plants. However, there is a high likelihood that a number of endemic and threatened species are being conserved. Community protected forests in Phek district may harbour some of India’s last populations of the Grey Peacock Pheasant, Mrs. Hume’s Pheasant and Blyth’s Tragopan. Khonoma, Zanibu and Chizami have been identified as Important Bird Areas (IBAs). Serow, Asiatic black bear and clouded leopard are other important species still found here. Leopards are reported from most places. Ecologist Firoz Ahmed of Aaranyak reports the presence of at least 25 amphibian species in Khonoma (15 of which were already known to the villagers), and of the Dark-rumped Swift (threatened) in Luzophuhu and Khonoma. In the absence of any extensive surveys, the floral diversity can best be gauged by the presence of around 40 species of orchids in Khonoma alone.

Absolutely no human use is allowed in the 20 sq. km. Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary. Only some regulated uses are allowed in the surrounding buffer area. A proposal is now being mooted to extend the sanctuary area, which will bring protection to several endemic and threatened species. Photo: Ashish Kothari.

The Movement Needs Help

It would be foolhardy to extrapolate from the above that wildlife is now safe in Nagaland. Even in many of the above examples, levels of protection vary. There remain major problems of inter-tribe and intra-village conflicts, corruption amongst political leaders, impact of contact with the outside world and its markets and the uncertainties caused by insurgency.

A major road-block is lack of support from government agencies. In mid-2005, the state’s wildlife authorities visited Khonoma and asked the Village Council to hand over the Tragopan Sanctuary area to the Forest Department in return for some funding! The Council rejected the offer.

Fortunately, there are more sensitive officials within the state government willing to work out more meaningful and long-term conservation strategies with the villagers.

During a workshop in February 2005, organised by the state government, the Centre for Democracy and Tribal Studies, and Kalpavriksh, the need to support such community initiatives was discussed. This would involve helping them assess the precise area under conservation and undertake an inventory of the flora and fauna. Other help required includes mapping, uniting various village initiatives, orienting village youth, and eventually coming up with a state conservation policy and plan after district and tribe-level consultations. Given its past history, what Nagaland is witnessing is nothing short of revolutionary. For village after village to declare no-hunting and no-deforestation zones, and for the local people to show that they want to and can sustain nature conservation actions, are no mean feats. With a little recognition and sensitive support, the Nagas could demonstrate that wildlife has a future, in the hands of those who live closest to it.

Community Reserves: Would They Work In Nagaland?

The Nagaland government is reportedly considering declaring some of the conservation initiatives by villages as ‘Community Reserves’, under Section 36C of the

Wildlife Protection Act, 2002. Will this help consolidate the initiatives?

We think not, at least not in the present avatar of Community Reserves (CRs). One of the biggest problems is that the Act specifies one uniform structure for all CRs, consisting of five villagers nominated by the panchayat/gram sabha and a forest officer. There are a wide range of institutions that manage conservation initiatives in Nagaland, from the Trust in Khonoma to the Reserve Committee in Sendenyu to the village youth associations of Phek district. Requiring all these to be converted to the structure laid down in the Act would destabilise the community effort. The requirement of including one forest official on the CR committee is a difficult proposition with the understaffed forest department, and given experiences such as what happened at Khonoma. More initiatives will be required to forge a greater working relationship between the forest department and the communities. The provision that land use in a CR cannot be changed without the permission of the Chief Wildlife Warden will also be a sticking point. Why would communities want to surrender their control over land use, when they already have a strong village council, which works as a monitoring body? Many Nagas realise and value the uniqueness of their land and culture and this is why they ask “Can’t we think of a Naga way of conservation? Why borrow models from outside?”