Time Travel Through Kashmir

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 12,

December 2020

Fossil-abundant Kashmir can help us to understand our planet’s last recorded mass extinction. But as Mahmood A. Shah writes, this will need the people of Kashmir and our government to recognise the immense worth of this fossil treasure and protect the sites currently being vandalised with impunity.

Trekking in South Kashmir, I took a moment to rest awhile and replenish the water lost through perspiration along the trek route I had taken. Looking around me, I spotted a rock that looked decidedly unusual. Walking up to it, I discovered to my utter delight that it was studded with fossils. Clearly too large to carry, I recorded its coordinates, took a few photographs and headed straight back to my office to check out what I had seen. It turned out they were coquina fossils, something unique that I could not find in our museum. It was a sedimentary rock studded with mollusc shells, trilobites, brachiopods, and all manner of invertebrates.

In 2015, when I was in charge of the Directorate of Tourism, a retired geologist, Abdul Majeed, walked in to meet me and said that just 15 km. from my office was a site of immeasurable geological significance, Guryal. It was probably the only site in the world where the Permian and Triassic (PT) boundary was clearly evident. On one side of the ravine, he informed me, were Permian fossils and on the other an abundance of Triassic fossils.

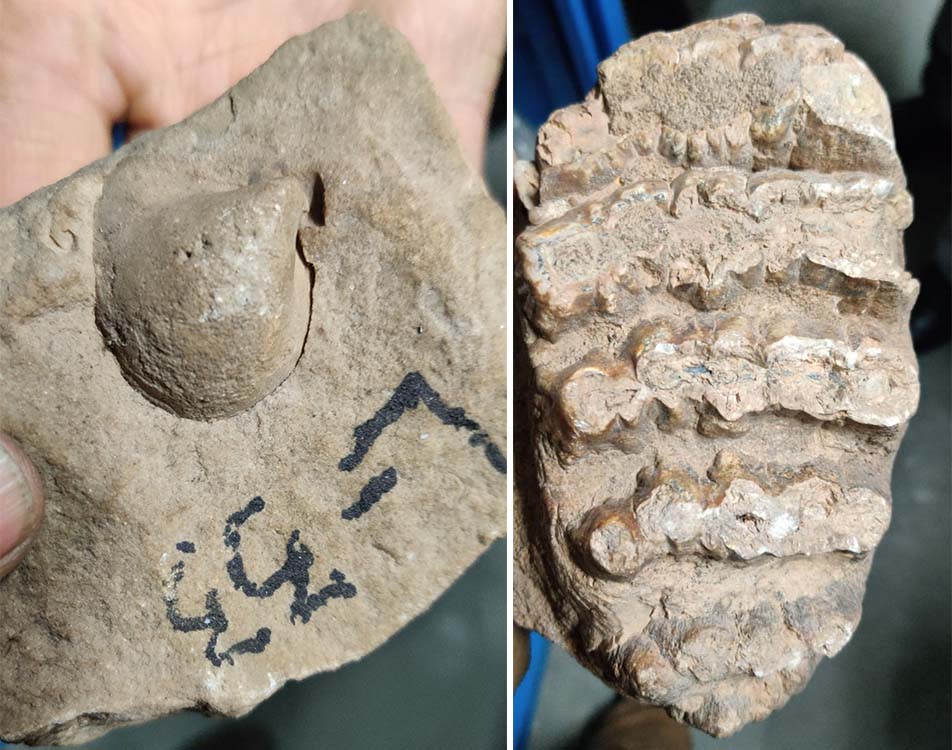

Fossils of gastropods, shelled invertebrate molluscs, are the commonest finds, with their shells naturally well-preserved. Photo courtesy: Mahmood A. Shah.

This was probably one site where evidence of planet Earth’s third mass extinction was visible, he said without emphasis. His words filled me with dramatic wonder. Back in 2016, I received a communication from the University of Kashmir to extend support to a group of geologists on a Kashmir tour. Driven by the idea of promoting geo-tourism, I delightedly accompanied the geologists and fully supported their survey. And what a rewarding experience!

I hadn’t forgotten about my meeting with Majeed. I drove to Guryal to learn about the PT divide. I was appalled. The site had been vandalised by illegal quarrying. I instantly initiated steps for its preservation and wrote a detailed proposal to the District Magistrate highlighting Guryal’s importance and the imperative of protecting it for research and for posterity.

The District Magistrate Farooq Ahmad Lone IAS, was a botanist, and immediately entrusted the site to the care of the Tourism Department to develop it as a fossil park… the first of its kind for Jammu and Kashmir. I threw myself into the mission and roped in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Kashmir and Shakeel Ramshoo from the Department of Earth Sciences in the University of Kashmir to guide my adventure. The preservation of Guryal soon began in full swing. I also connected with Riyaz Mir, a geologist with the Geological Survey of India (GSI) whose paper Developing Geological Heritage of Kashmir I pored over. He recounted how the GSI had operated a campus at Ashmuqam, a village en route to Pahalgam, where young geologists were stationed for a six-month orientation before being sent for another six months to gather field experience. In the campus, the GSI had even set up a Fossil Museum, but when we visited in 2018, we discovered that the museum was defunct and had been converted into a security establishment.

Nestled between the Pir Panjal mountain range and the Greater Himalaya, the fossil site Guryal and the larger Kashmir valley present an undulating vista of lakes and evergreen forests, together with their hidden geological treasures. Guryal is probably the only site in the world where the Permian and Triassic (PT) boundary is clearly evident. Photo courtesy: Mahmood A. Shah.

A Mammoth Discovery

My interest took me to the Shri Pratap Singh (SPS) Museum in Srinagar, J&K. Proposed in 1889 by Maharaja Pratap Singh and inaugurated in 1898, the museum houses a collection of over 80,000 objects from various regions in North India. The museum also boasts rare artefacts representing the rich heritage of J&K. Incredibly, I saw a mammoth Mammuthus primigenius skeleton here, but no one seemed to know how it came to be part of the museum collections. My curiosity aroused, I read up all I could and unearthed the fact that a German geologist by the name of Helmut de Terra had visited central Asia in 1927-28 as part of a German-Swiss expedition.

Travelling via the Himalaya to Tibet and Chinese Turkestan, he spent time in the Eastern Himalaya and later undertook several expeditions to Kashmir in India. He even produced a glaciological map of the Eastern Himalaya and advanced the theory that humans were established in Asia almost as early as in Africa. He was the one who discovered the first mammoth skeleton in Kashmir, according to Khalid Bashir, a retired Director Information and a noted writer. Maharaja Hari Singh actually used the skeleton as a coat-hanger!

While we are justifiably proud of the living heritage of Kashmir, we should also be cognisant of the immense value of its ‘non-living’ heritage, which includes the fossils I write about on these pages. Sadly, however, the SPS Museum has had more than its fair share of turbulence. There was utter neglect of this irreplaceable collection of over 80,000 artifacts ranging from a blend of Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic displays of culture, costumes and art, to instruments of war. The collections were moved to a new building in 2014, but a mere 30 per cent of the original artifacts are on display because the construction has not yet been completed. The mammoth skeleton, of course, is not yet on display in the new, yet-to-be-finished building.

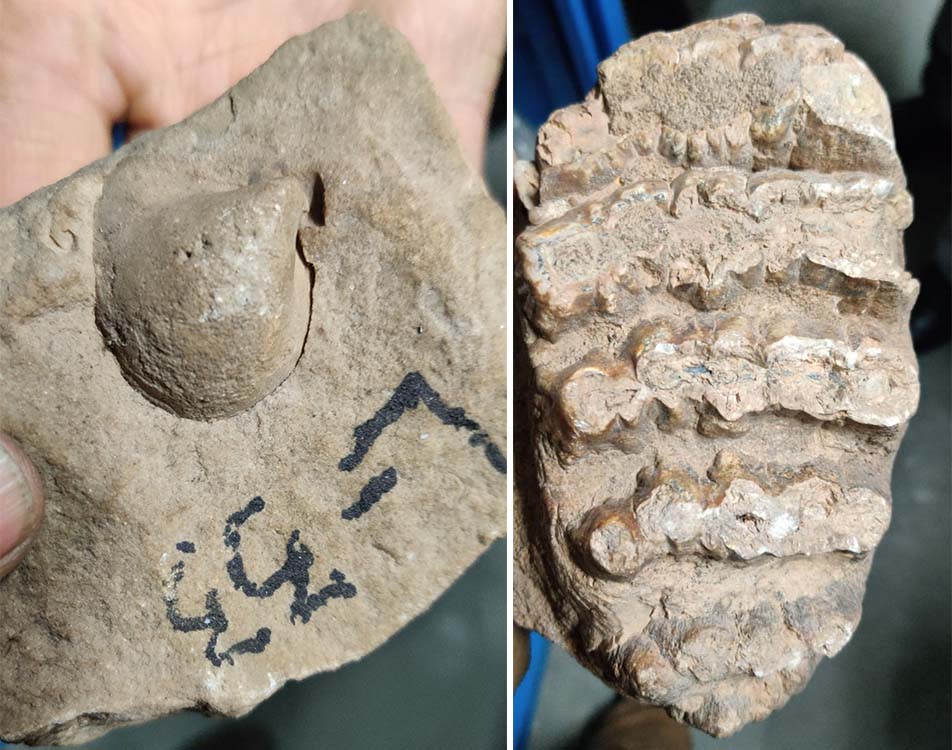

(Left) Bivalve fossils were formed when the sediment within which they were buried hardened into rock over millennia. They usually sport bowl-shaped shells that once encased their soft bodies. (Right) The fossilised molar of an ancient elephant displays a series of knobby ridges that ran along every tooth, similar to those of modern elephants. Photo courtesy: Mahmood A. Shah.

Interestingly, in 2001, news reports appeared regarding the discovery of yet another ‘mammoth’ skeleton close to the site Majeed Sahib had mentioned. Towards the end of the Pleistocene epoch, woolly mammoths were found in Western Europe, Northern Asia and the seaboard of North America. How, one wonders, did their tropical progenitors adapt to the cold north? All the elephants we see today, shared a long-extinct common ancestor (Gomphotherium) with the woolly mammoths. The discovery of the second mammoth skeleton discovery remained in the news cycle for quite a while and the skeleton was later transferred to the Wadia Museum of Natural History in the Jammu University.

Dr. G. M. Bhat, who headed Jammu University’s Baderwah campus, exhumed the remains of what we thought might be a mammoth, which eventually turned out to be a straight-tusked elephant. Dr. Bhat accompanied me to the discovery site. We had to wade through narrow lanes to enter a compound where we saw a Kerawa formation that had yielded the elephant skeleton when soil was excavated to construct the Banihal-Baramulla railway line. In situ preservation could and should have then been made, but that moment is gone and the site has been lost forever.

Fossil at Wadia museum. Excavations from the Gallander village in Pampur is believed to have unveiled one of the largest and earliest-known fossils of mammoths and evidence of ancient human civilisations. Photo courtesy: Mahmood A. Shah.

The Crash That Created Kashmir

Alferd Wagner, a German scientist, is credited with coining the theory of continental drift. He discovered fossil species on the shores of Greenland and Europe that were similar. This led him to postulate that Greenland and Europe must have been one land mass at some point of time. Similarly, Pangaea the supercontinent split up into Laurasia and Gondwana. And Gondwana later drifted into separate land masses and gave rise to Asia, Africa and Australia. Interestingly, it was an Austrian scientist, Eduard Suess, who named Gondwana (“forest of the Gonds”) after a region in Central India where some of the earliest known rocks and unique fossil assemblages were found.

Fascinated by the geology of Kashmir, I enlisted the help of geologist Riyaz Mir who first took me to a Gondwana fossil bed, that lay a few hundred metres behind the world-famous Mughal garden created by Saif Khan, the brother-in-law of Emperor Jehangir in 1633. Yet another Gondwana fossil bed exists near the Banihal tunnel. And we also have the fossil beds of Zewan, formed when Kashmir was still submerged under the Tethys Sea or the Neotethys, which was an ocean during much of the Mesozoic Era.

On either side of Guryal lie fossil beds that showcase an impressive diversity – ammonites, branchiopods, bivalves, gastropods, Rhacopteris and even fish fossils. As the drift of the Indian plate moved northward to crash into Europe the collision created the Himalaya. The rising land resulted in the water of the Tethys sea draining away, leading to all its land-stranded aquatic life perishing. Thus, the fossils we now see. The climate of Kashmir then was warm and conducive for tropical fauna including elephants, rhinos and even giraffes, whose fossil remains have been discovered in Kashmir.

It was the emergence of Pir Panjal Range roughly four million years ago that enclosed the Kashmir valley from all sides and made it a closed ecosystem. In this little cup of biodiversity, the European red deer Cervus elaphus is believed to have separated and evolved into a separate species, the hangul Cervus elaphus hanglu. All the tropical species unable to adapt to these massive changes, vanished, as did all the marine life.

Countless age-old Triassic wonders continue to be unearthed across the Kashmir valley, revealing evidence of the planet’s third mass extinction. This includes a fossil of a prehistoric fish (top left) and a rhacopteris fossil (above) extracted from Pahalgam town. Photo courtesy: Mahmood A. Shah.

Geological Tourism

Kashmir is without doubt one of the most attractive places for visitors to spend time contemplating the beauty and wonder of the world. This ‘Happy Valley’ may have passed through trials and tribulations, but those in the know have experienced the instinctual friendliness and hospitality of the smiling people of Kashmir. Apart from blue skies, and the biodiversity of verdant forests, crystal rivers and avian-stocked lakes, the fossil marvels around Ashmuqam and Phalgam, and Kokernag, and those in Kulgam, Shopian and Gulmarg (around Butapathri) can be effortlessly built into unforgettable itineraries that visitors would relish and learn from.

I am an inveterate trekker, photographer and chronicler of the mountains and their incredible wildlife. But I have to say, the worth and scale of the species we see today come into sharp focus when you consider their long passage through time.

It’s not as though the fossil wonders I extoll are not visible elsewhere. The entire Himalayan Range is studded with such reminders of time past. For instance, Himachal Pradesh’s Langza village is justifiably reputed to be India’s fossil hamlet. Located at an altitude of 4,450 m., some 418 km. from Shimla, it takes roughly 12 hours to reach the fascinating site. But the location is inaccessible for half the year because it is totally snowbound. Compare that to Kashmir, accessible round the year, and the penny drops. There are few places that compare with Kashmir, which should be on everyone’s bucket list.

Sitting at Guryal next to a fossil bed, approximately 250 million years old, I contemplated the upheavals the land before me had witnessed. By comparison, Homo sapiens has not even been around for the blink of an eye. Yet we have inexpertly created an epoch of our own, the Anthropocene, that threatens not just every other lifeform on Earth, but our own as well. My purpose of penning my thoughts down here is to share with the very huge Sanctuary Asia network the reality that we are now the agents of change responsible for the sixth great mass extinction that is staring us in the face. The clock in fact has already started ticking.

The International Geological Congress that was scheduled to be held in Delhi in November 2020 was expected to have formalised the idea of promoting Kashmir’s geological treasures. The COVID-19 pandemic put paid to that. We now expect it to be held in August 2021 and with Sanctuary and its longterm association with Kashmir, we hope to coalesce a large number of experts from different sectors – geology, botany, zoology, social sciences, history, culture and academics. And to draw the attention of the world to the new tourism potential of geological adventure as seen through the eyes of Kashmiri experts, young and old, and their association with some of the world’s finest geologists.

Mahmood A. Shah is a senior Kashmir Administrative Services officer and Former Director of Tourism, He is an inveterate trekker and geology buff.