The Story of India’s Cheetahs

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 10,

October 2023

With improved technology and a much greater appetite among the young for books to remind them of the wonderful biosphere in which they live, it is heartening to see how many new, high-quality publications are emerging from within India. Here are books that Sanctuary believes should be in every public library and in the homes of all those whose hearts beat to nature’s drum.

The Story of India’s Cheetahs

By Divyabhanusinh

Published by The Marg Foundation

Hardcover, 322 pages, ₹ 2800

The cheetah has recaptured our attention in the past year, when India undertook the ambitious project of introducing the species! The outcome of the project notwithstanding, I was definitely curious about the life (and disappearance) of the feline in India. And Divyabhanusinh’s book could not have come at a more opportune moment. The book travels through time as the author unveils the life of the cheetah in India from 2300 BCE, as portrayed in jagged prehistoric paintings in cave shelters, to travelling on carts for hunting expeditions, and to being reduced to skins as the result of shikar.

About 30 years ago, in 1995, Divyabhanusinh, a conservationist who has championed disappearing wild species, authored The End of a Trail: The Cheetah in India, an exhaustive book about the species in the country. The Story of India’s Cheetahs is a revision and update of the text of his first work, to include the cheetah introduction programme. Divyabhanusinh, a close associate of Sanctuary Asia, has been the President of WWF-India, and a member of different national and international bodies for wildlife, such as the IUCN’s Cat Specialist Group. He was also a part of the Cheetah Task Force when it was constituted by then Environment Minister, Jairam Ramesh, when the reintroduction of the cheetah was discussed in 2009.

The book delves deep into the life of cheetahs in different geographies, cultures, languages and texts across different periods in India. This is a book for wildlife as well as history buffs.

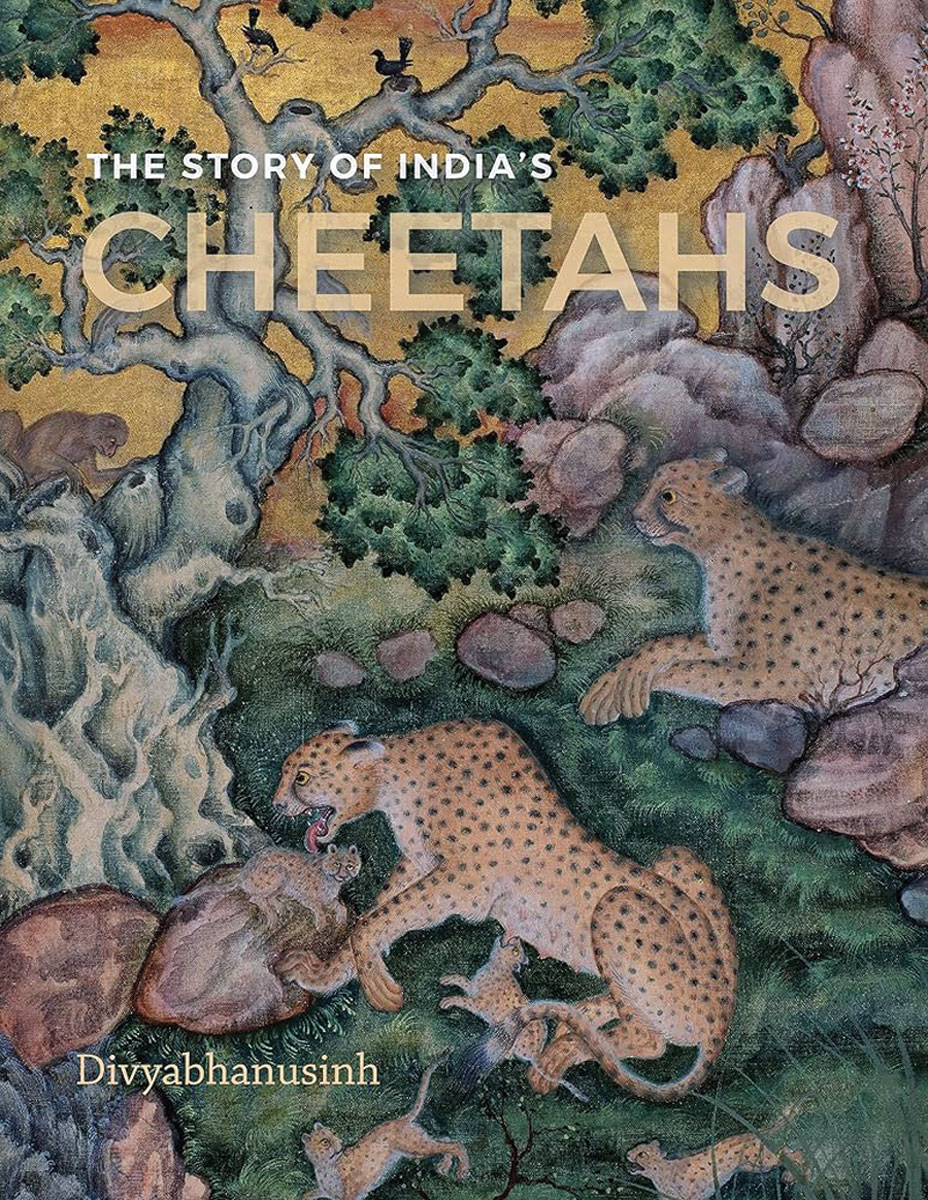

Along with the text, the book is studded with plates of cheetahs represented in fine art miniatures painted during the reign of the Mughals. A particularly impressive recreation in the book is one of a painting dating back to 1570, attributed to Indian miniature painter BasÄwan. This depicts a cheetah family, with two adult felines and four cubs, in a rocky landscape under a towering tree. This is said to be the earliest record of the cheetah in the wild in India. The Mughal Emperor Akbar is known to have kept 1,000 cheetahs in his stable, and is believed to have possessed as many as 9,000 over the five decades of his rule.

The section on British rule in India is the proverbial smoking gun, detailing the lengths to which they went to enjoy a ‘pastime’ they could not find at home. The author also notes the explosion in documentation of the cheetahs, from numerous accounts of shikar to art and naturalists’ observations. Several cheetahs were also shipped to Britain. Additionally, the author painstakingly records the last few sightings of the cheetah in India. And when was the very last of these wild cats spotted in our country? Read the book to find out!

The extensive records of shikar help understand the historical range of the cheetah, its prey, its hunting style, its interactions with humans and other animals. The Mughal practice of trapping and training cheetahs for hunts has generated a wealth of information on the cat. An entire chapter is dedicated to such manuals, which also include illustrations, highlighting the relationship between people and cheetahs. The author ruefully points out that modern Indian zoos seem to have learnt nothing from the old management traditions.

The author dismisses other theories about the cheetah, including the one that all cheetahs in India were brought from Africa, with documentation from across the centuries.

After presenting historical evidence in relation to humans, the author leaps into the biology of the cheetah and its lineage. Employing genome analysis, studies of skulls and skins, and other techniques, he highlights how closely related different cheetahs are to establish whether African cheetahs could/should be introduced in India.

In the last chapter, the author discusses the rationale and prospect of introducing cheetahs in India. Since the 1950s, when the administration realised that the cheetah was in danger, discussions on initially preserving and then, by the 1970s, introducing cheetahs have been ongoing. The current programme of cheetah introduction moved forward in fits and starts from 2009, with many twists and turns in the form of court orders, and several stakeholders. The book goes on to explain just how it came to fruition, including the controversy surrounding it.

One overarching point made by the National Tiger Conservation Authority presented by the author is that the reintroduction/restoration of a flagship species (such as the cheetah) is an ecosystem restoration programme in much the same way as the protection of the one-horned rhino ensured the survival of Kaziranga’s grasslands, or the way the protection of the Asiatic lion helped protect the scrub grasslands of Gir.

Reviewed by Shatakshi Gawade.