The Long Restoration of Byrasandra lake in Bengaluru

First published on

June 21, 2023

By Priyanka Das

On A Mission

It was a monsoon evening in 2016. We were in the final year of our Bachelor’s degree and, like most other days, we were discussing Green Army (GA) activities after class. GA is a student conservation group at Christ University in Bengaluru, that was founded by Dr P. U. Antony in 2001. To celebrate World Wetlands Day in 2017, we had already organised a national conference on wetlands. We were busy planning the event when the dire condition of the lakes in Bengaluru and the lack of any conservation action on our behalf struck us. Being the enthusiastic young hearts that we were, we decided to restore a lake; that we did not have a single clue about the process did not faze us. Within an hour, after a dive into the internet, we knew that the lake we wanted to restore was Byrasandra.

The next morning my peers Arpitha, Ritobroto, Minoti, and I could not wait to break our new idea to Dr. Antony, our zoology professor. After listening to our over-ambitious project, he didn’t discourage us, but neither did he indulge us. All his years of practical experience told him that the goal his optimistic students had envisioned would not be a cake walk. On the other hand, our spirit was invincible, owing to our inexperience and an almost complete absence of images of the real world.

As Green Army first saw the lake in 2016. Courtesy Priyanka Das.

Our primary motivation for choosing Byrasandra lake was its proximity to our campus – just two kilometres walking distance, which made it convenient for us to visit after classes. We were out in the evening to find our mission lake the same day that we broke our idea to Dr. Antony. Making our way through narrow lanes of a slum in the 3rd Block of East Jayanagar, we arrived at our lake, which was then just a depression with a small pool of water where kids were catching tank cleaner fish Hypostomus plecostomus. The lake bed was around 15 acres, the depth at the centre was around three metres, and its outlet was blocked by solid waste. Layers of garbage were deposited on the periphery of the lake and there was a continuous influx of sewage from the adjoining slum, along with open defecation, in the main body. Beside the main lake body, there was a non-functional immersion tank and a eutrophied water body connected by a blocked inlet. One side of the lake had a few trees, and the only plants one could see were castor Ricinus communis and Congress grass Parthenium hysterophorus. The presence of anti-social elements was hard to overlook as well. We stood facing the lake, absolutely overwhelmed by the condition of Byrasandra. It will be a lie to say that we did not shudder thinking about the massive task that awaited us, but it did not demotivate us from our resolution to restore the lake.

Seeking Support

The abysmal condition of Byrasandra was representative of the lake system in Bengaluru, whose citizens tend to remember them only when a certain Bellandur lake catches fire or the flooding city becomes a matter of inconvenience. With no perennial river in the vicinity, Bengaluru has historically expanded with the creation of water bodies. These manmade lakes were interconnected and monsoon fed, where the overflow from one lake flowed into another downstream. Unfortunately, when the city started pumping water from Cauvery river, the lakes lost their importance and their number dwindled to make way for the haphazard growth of India’s Silicon Valley. Today, the terms ‘kere’ and ‘sandra’, which mean lake in Kannada, are irrelevant suffixes in the names of places, and the remaining lakes are on ventilator support.

The lake after occasional showers. Courtesy Green Army.

Artificial islands being constructed on the lake. Courtesy Green Army.

When we began our restoration journey, the book Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future by Dr. Harini Nagendra from Azim Premji University had already been published, and some of us had read it. As regular visitors of the Kaikondrahalli lake to watch birds, we were aware about Dr. Nagendra’s efforts in restoring the water body with public participation. Hence, we knew for sure that we had to seek help from Dr. Nagendra. Very soon, on another rain-washed morning, we found ourselves visiting her, and were greeted by that ever-so-warm smile. It was because she generously held our inexperienced, unskilled and uninformed hands that we knew which path to traverse on, despite its arduous nature. We are also immensely grateful to Dr. T. V. Ramachandra from Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, for his initial guidance.

Whose Lake is it Anyway?

Although there were newspaper articles about the two-decade-long legal battle fought by Venkat Subba Rao to prevent encroachment of the lake, the first hurdle before us was to unearth the convoluted history of the lake and find the authority to which the lake belonged. What followed was an unending series of disappointments – email exchanges, being refused and granted appointments, and visiting government offices. On the brighter side, by then our juniors had joined us, and it wasn’t just the four of us racing between final year research projects and the restoration resolution. Our treasure hunt continued until one day, we finally got hold of the key to look through yellowed, dusty documents in a forgotten cupboard of an administrative building to our hearts’ content. Meanwhile, our determination convinced Antony Sir, so much so that he opted to be officially appointed as the Warden of the Byrasandra Lake.

In 1985, the Karnataka government had formed an expert committee under N. Lakshman Rao to maintain a desirable environment of lakes in Bengaluru. After the study was completed in 1988, the government issued a notification that all unused tank beds should be handed over to the Horticulture/Forest Department. For Byrasandra, the Committee decided to partly maintain the water sheet and requested the Forest Department to check the feasibility of developing a tree park on the lake's shore, for which 10 Ha. was allotted. Between 1992 and 1998, the then BCC (Bangalore City Corporation) filled part of the lake bed with debris to make way for slums shifted from NIMHANS. For the same, the residents of the RBI Colony in Jayanagar 3rd block filed a PIL in High Court (HC), and got an order prohibiting lake-filling and further encroachment on the lake bed. A long trial ensued after this, which lasted till 2004, on various issues between the residents, writ petitioners and the then BMP (Bengaluru Mahanagar Palike). Finally, in 2004, BMP budgeted Rs. 120 lakh to develop the lake, which however did not translate into action.

To make things worse, in 2005, the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) notified a public auction of Byrasandra. The lake was offered as collateral security to Indian Overseas Bank (IOB) for credit facilities availed by One Sierra Developers (One Sierra defaulted on a loan taken from IOB’s Jayanagar Branch, for which the lake was used as collateral. This was illegal, but the bank proceeded to collect it as its dues.). Residents and RBIEA (Reserve Bank of India Employees Association) filed a PIL in HC to grant a stay of the proceedings before DRT. Initially, the HC did not order a stay, but in a notice declared that the lake was sold for Rs. 7.6 crore in a public auction. When the residents approached the HC once again, a stay was issued. Next, an objection was filed by the then BMP with the IOB, which was dismissed, and a criminal complaint was filed by the Deputy Commissioner for Forests (Bangalore Urban). After a long haul, in 2011, it was the citizenry’s triumph when the HC disapproved the auction by DRT and handed Byrasandra lake over to BBMP (Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagar Palike). Since then, the lake is under the BBMP’s jurisdiction, but Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) is in charge of its development. IOB filed a Special Leave Petition in Supreme Court, but it was fortunately dismissed.

The Restoration Effort

Followed by a Guddali Puja for lake rejuvenation in 2013, the BBMP councillor of ward number 153 started work on the lake. They worked on fence installation and repairing, cleared the overgrown vegetation on the lake bed and demarcated three parts in the lake. Byrasandra is a part of the Puttenahalli Lake series within the Koramangala-Challaghatta Valley. The inflow sewage was redirected towards Agara- Bellandur bed further downstream, leaving the survival of the lake to the mercy of monsoon showers and occasional rains. Earlier, the inflow brought in water from a catchment area encompassing NIMHANS region, Gulbarga colony and Tilaknagar, among others. In 2014, Venkat Subba Rao received the Namma Bengaluru Award for his unparalleled efforts to save the lake. Rao was instrumental in providing valuable guidance to us at various stages as well.

From the initial days of our involvement in 2016, we began associating and interacting with various government bodies, local authorities and residents living on the periphery of the lake. The BBMP councillor Gangambika Mallikarjun welcomed the collaboration and technical assistance with open arms. Since then, Green Army’s main role has been mediating, mobilising and monitoring. We started by conducting a series of socio-economic and ecological surveys to gather a comprehensive understanding of the lake and people’s reliance on it. To bring forth the spirit of urban commons, one of the first major activities organised by GA was a clean-up drive in March 2017. This involved the local residents, BBMP workers and NGOs, among others. To take the spirit further, two tree plantation drives of native species were organised as well.

As the lake was solely rain fed, water couldn’t be retained throughout the year, interrupting the proper functioning of the ecosystem. In Bengaluru, sewage and stormwater drains are the same and all the lakes are interconnected, so starting the functioning of the inflow and outflow with the installation of sewage treatment plants (STPs) or bio-remediators was of immediate importance. We received valuable inputs from S. Somashekhar, Chief Engineer of Lakes, BBMP for this, and approached Biome Solutions. The scientific team at Biome helped us with testing the possibility of phytoremediation but as it failed, STPs were looked into. On reaching out to the BDA, they shared detailed information on different STP designs and costs involved. Initially, the local councillor had shown willingness to incorporate the design but later BBMP refused to work on this seriously until the action came through a proper company. After this, the then GA members, went back to Biome. Despite a lot of back and forth, unfortunately, the Biome team decided not to take up long-term work on the lake with GA because they weren't confident that the future batches of our college would take it forward.

By the end of 2018, restoration activity at the lake had been absent for almost a year. However, in 2019, at an estimated cost of four crores, BDA finished their restoration work, which involved strengthening of bunds, silt removal, laying of pipes and drains for sewage water and construction of stormwater drains. A complaint was lodged by the residents and activists that since the inflow was started in the absence of an STP, the lake had transformed into an unhygienic mosquito breeding ground. Following this, the lake development charge was transferred from BDA to BBMP. The local councillor assumed responsibility for the further restoration work involving construction of an STP at a budget of two crores. But not much difference was observed in the lake. With the COVID-19 pandemic, volunteers could no longer engage with lake restoration post 2020. Some students visited the lake in 2021, and found the lake in an abominable condition, with only a small puddle of water and artificial islands being constructed on the lake bed.

A New Morning

The year 2022 turned out to be a pleasant surprise for GA volunteers, both old and new. Water levels had risen, greenery was flourishing and the birds flocked there indicated good functioning of the ecosystem. These observations were not transient, as students made frequent visits, and the seemingly healthy functioning of the lake sustained their smiles. After the BBMP resumed lake development charges, the STP was installed, from which the treated water is directed to the smaller wetland before entering the main lake body. The smaller wetland has been modified into a reed bed system for the water to undergo further bioremediation. The idol immersion tank does not exist any longer – it has been filled up and transformed into an ornamental plant garden. A wall has been erected on the side of the lake that shared a boundary with the slum. A huge number of people visit the lake now, to walk or jog on the completely concretised path around the lake, and excited children congregate in the children’s park, which is under construction. Regular clean-up of garbage and periodic weeding takes place. There are lights and strict security guards who do not allow even GA volunteers to enter beyond the stipulated time period.

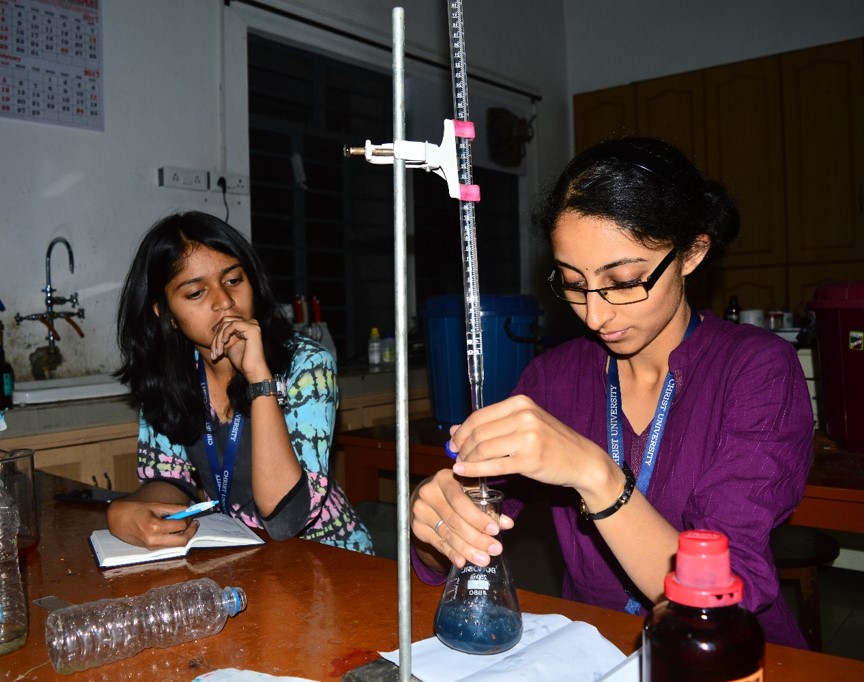

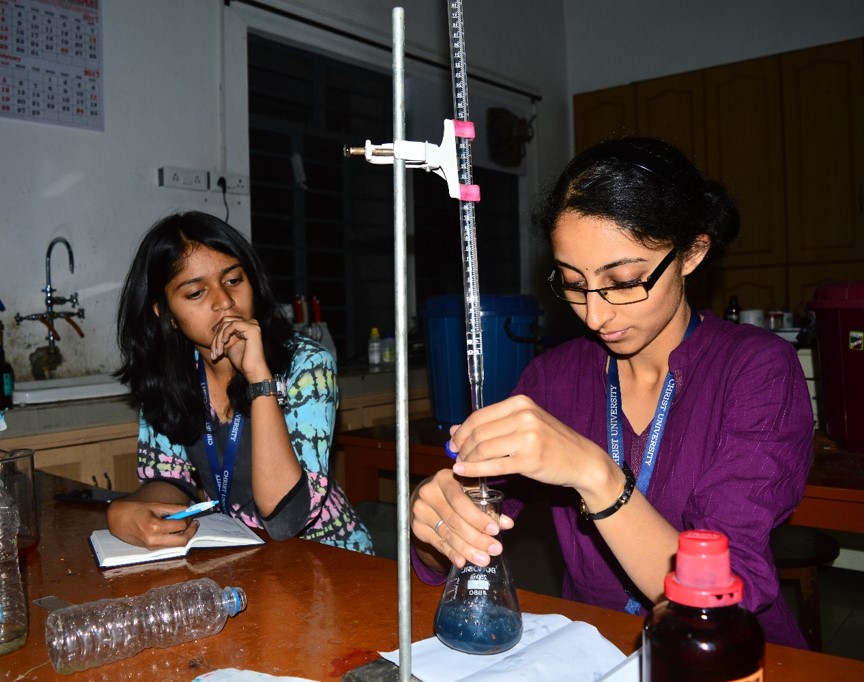

Testing Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) as part of the initial socio-ecological survey. Courtesy Priyanka Das.

Phytoremediation system in the lake at present. Courtesy Priyanka Das.

Restoration of the Byrasandra lake tells a multi-layered story. It speaks volumes about what residents can do when they care about their environment. The relentless spirit of the citizens of the RBI colony to protect and preserve Byrasandra lake deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as the people’s movement to save Mollem in Goa or the Dongria Kondh’s struggle against Vedanta’s bauxite mine in Niyamgiri. Local authorities, who are often thought to be powerless, can indeed make and break bridges, when genuine willingness is their strongest pillar. The BBMP councillor showed how resources can be honestly used to bring stark changes in no time.

Last but not the least, it is a story of GA – seven batches of young students driven by a belief in environmental conservation and their enabling mentor, Dr. P. U. Antony. For GA, it is both a battle lost and won. On one side, the healthy water table, return of flora and fauna, starting of inflow and outflow with an STP and bioremediation system in place, and the reclamation of an urban common space makes us brim with happiness. On the other hand, the exclusion of fishermen, the plantation of non-native plant species, the filling of the immersion tank, an ornamental garden in place of a medicinal one, and concretisation of the walking path which prevents water seepage makes us ponder about our inabilities. It was probably due to the lack of involvement during the global pandemic, maybe battles are always about some compromise, or maybe the granite benches that will last beyond our time will continue to remind visitors about GA’s involvement. However, the new GA volunteers will engage with the local authorities again to rewrite some of the disappointments, besides their continuous monitoring activities. Nonetheless, if and when you visit the Byrasandra lake in the heart of Bengaluru today, remember it is not just another lake, but a place that has efforts etched in its banks, and echoes the emotions of innumerable individuals.