The Call of the Cheetah

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 12,

December 2020

Only time will tell, suggests Abinaya Kalyanasundaram, whether the ambition of bringing cheetahs to India will end up being a fallacious pursuit of vanity in the guise of conservation, or a triumph that could potentially overshadow the success of Project Tiger!

Its reputation as the fastest mammal on land has long fascinated the world. It sprints at incredible speeds, its body light and graceful, swerving deftly after its prey. It is a phenomenal hunter. But it’s not known for its ferocity. On the contrary, the cheetah Acinonyx jubatus, is a relatively docile big cat, a trait that historically worked to its disadvantage... it was easier to domesticate. Ancient Egyptian royalty kept cheetahs as pets, capturing them from the wilds and using them to assist in hunts. In India, too, the Asiatic cheetah faced a similar fate. Thousands were trapped, tamed and trained in the Mughal era, to be used in a sport called coursing. They never bred well in captivity, and so were indiscriminately captured from the wild for decades. In the British colonial period, trophy hunting decimated the remaining populations, while their grassland habitats, labelled “wastelands”, were converted into agricultural land or planted with trees for commerce. In India, the cheetah was declared locally extinct in 1952, the only large mammal to suffer that fate after Independence. Fewer than 50 individuals of the subspecies Acinonyx jubatus venaticus survive in Iran.

A Decades Long Dream

India has been trying to reintroduce cheetahs for several decades. A proposal struck with Iran to exchange a few Asiatic cheetahs for Asiatic lions fell through after political complications arose. Talks of cloning ensued in the 2000s, but it was in 2009 that the idea of translocating African cheetahs to India took shape. Surveys and talks began in earnest, but in 2013, the Supreme Court (SC) stayed the project calling it “arbitrary and illegal”. The SC also highlighted the potential conflict with Asiatic lions Panthera leo persica, should the relocation go forward in the suggested site for both cats – the Kuno-Palpur Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh.

In January 2020, after an appeal filed by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), the SC issued an order for the project to go forward as a pilot test, after suitable study and habitat selection.

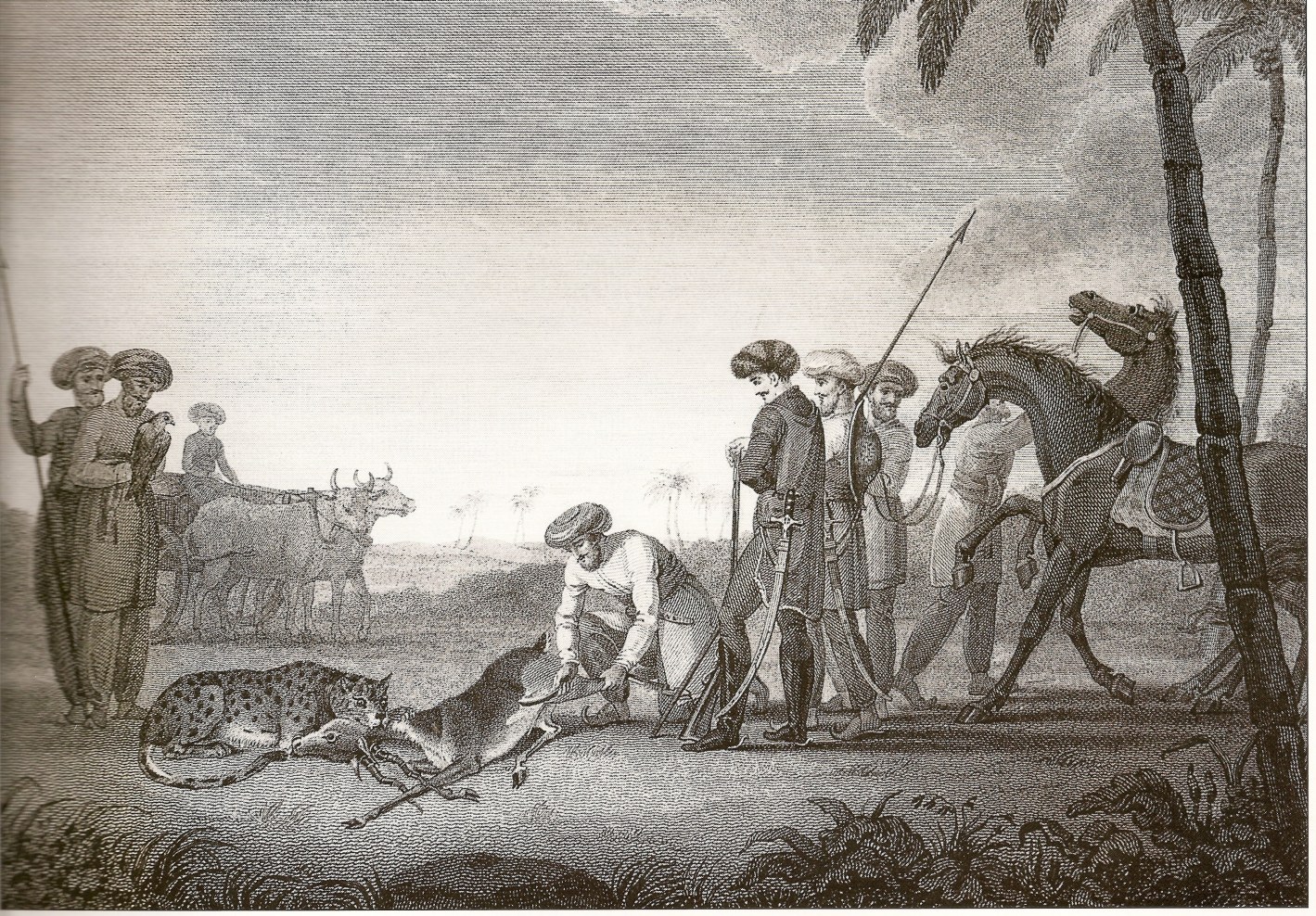

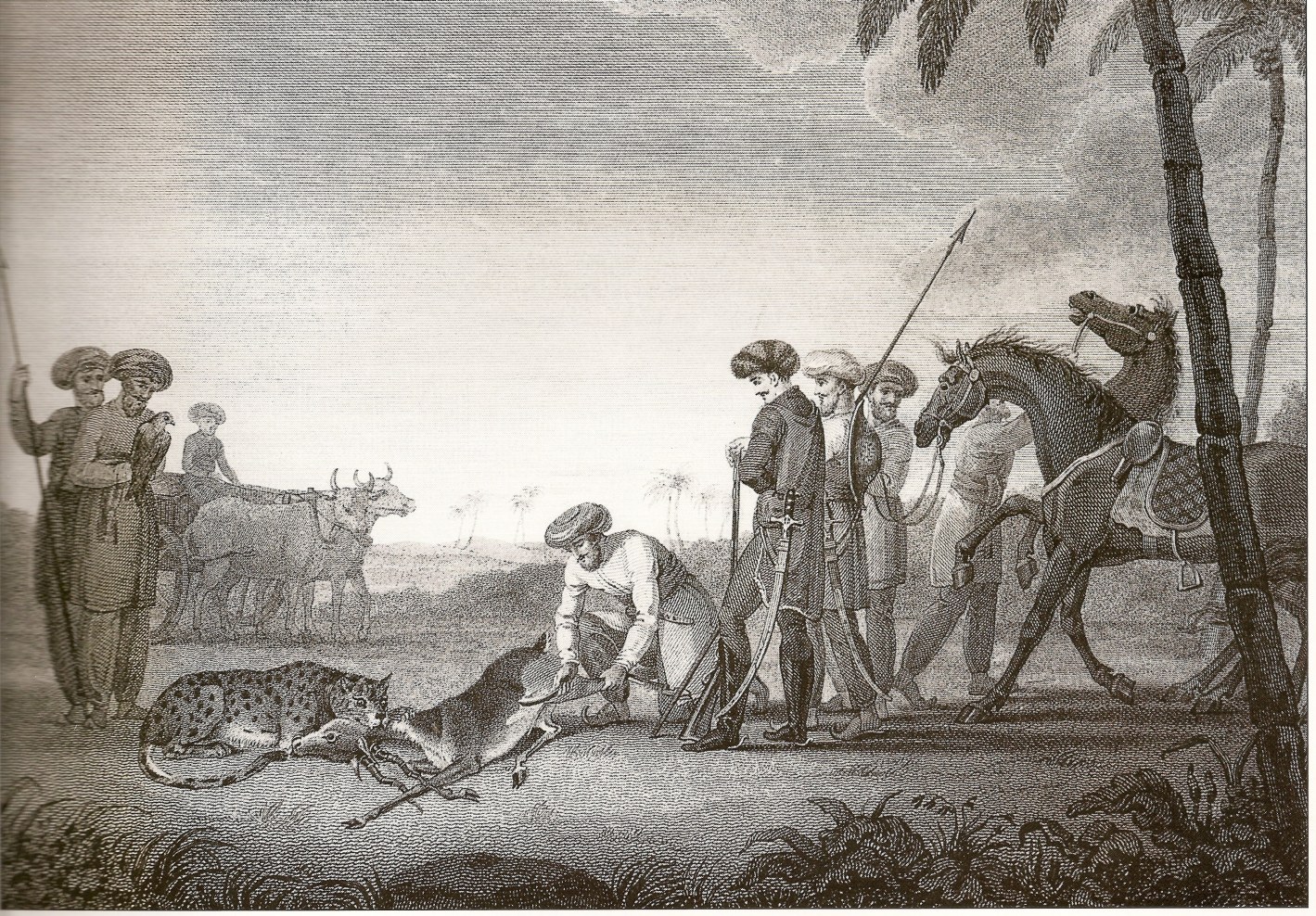

An artist’s depiction of the Mughal sport of coursing. The cheetah’s docility rendered it an easy target for indiscriminate capture and subsequent training for the sport. Photo: James Forbes, Oriental Memoirs, Vol. I, 1812/Public Domain.

Where the Grass Does not Grow

In the event, the proposal to translocate African cheetahs to India continues to be contentious. Dearth of suitable habitat and sufficient prey being the foremost contention.

Open arid or semiarid grasslands and scrublands, not forests, are best suited to the cheetah’s hunting style. Its long limbs, slender body, flexible spine and long rudder-like tail allow for high speed turns, making it a formidable pursuit-predator. It can accelerate to 112 kmph. (in under three seconds!), and open lands increase the chance of success. Cheetahs roam large distances. Groups of three or more males, usually siblings, form coalitions at around 18 months and may travel hundreds of kilometres in search of new territories that average roughly 80 sq. km.

Slender, nimble and sprightly, the cheetah is the lesser-celebrated king of the savannah. Might India’s disappearing grasslands provide it a successful homecoming? Photo: Aditya Dicky Singh.

If cheetahs are to be introduced, they thus need the promise of vast contiguous grasslands to sprint and hunt, and to procreate and disperse, creating viable populations.

A promise that India cannot deliver. Yet, at least.

Decades of exploitation have annihilated India’s grasslands, reducing them to degraded and disconnected islands. Vast swathes have come under the plough, converted to agricultural fields and livestock grazing grounds. Some fell victim to misguided afforestation schemes, irrigation projects, and, morerecently, solar panels and wind turbines. Less than one per centof India’s grasslands are effectively protected by law. Most have been demarcated as wastelands and are rapidly disappearing, together with the species that evolved to live in their fold -- the Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps faltering at the brink of extinction with just 150 alive in the wild, the endangered Lesser Florican Sypheotides indicus flutters in scattered pockets; populations of the blackbuck, chinkara and four-horned antelope, all important prey species for the cheetah, are dwindling. The Indian wolf and hyena are already victim to retaliatory killings... a fate that awaits any reintroduced cheetahs.

India has no policy in place to protect grasslands. A 2006 report submitted by a Task Force on Grasslands and Deserts, appointed by the Planning Commission, stated it best:

“Grasslands are not managed by the Forest Department whose interest lies mainly in trees, not by the Agriculture Department who are interested in agriculture crops, nor the veterinary department who are concerned with livestock, but not the grass on which the livestock is dependent. The grasslands are the most productive ecosystems in the subcontinent, but they belong to all, are controlled by none, and have no godfathers.”

The report went on to provide seven recommendations, including a National Grazing Policy for the sustainable use of grasslands and biodiversity conservation. Fifteen years later, there is no sign of any such policy.

Grasslands – the prime habitat of cheetahs – have been mismanaged almost to death in India, with only degraded patches surviving. Some experts suggest that grasslands and their wild denizens, would benefit from Project Cheetah, which aims to bring back the charismatic cat as the habitat’s ambassador. Photo: Kalyan Varma.

A Supreme Court-appointed committee – comprising former Director, Wildlife Trust of India Dr. M.K. Ranjitsinh, Director, Wildlife Institute of India, Dhananjai Mohan, and DIG, Wildlife, Ministry of Environment and Forests – are currently surveying potential cheetah relocation sites in three states, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, to study prey availability, habitat status, human-animal conflict potential and, most importantly, the contiguity of large grasslands.

The worry, of course is that even if the introduction is successful and a viable population is established, cheetahs will inevitably spill outside the designated area, into farmlands of communities on the fringe. They may not be a direct threat to human life, but they will predate on livestock. In Africa, where around 7,100 cheetahs live, 77 per cent are found outside Protected Areas, and conflict with livestock farmers is constant, warranting cost-intensive translocations to avoid retaliatory killings.

According to Dr. Laurie Marker, Founder of the Cheetah Conservation Fund, Namibia:

“Our research shows that cheetahs require huge areas for home ranges, of about 1,500 sq. km. This and their tendency to occur in low densities, requires that release sites should be part of a larger suitable landscape, or else metapopulation management becomes necessary.”

In a country where large predator-human conflict is already notoriously high, and resources notoriously low, cheetah introduction could aggravate tensions. According to conservation biologist Dr. Sanjay Gubbi:

“In most cases, the ex-gratia can take months, and falls short of the market price of killed livestock. Are we ready to address the problems of communities immediately, proactively, and with adequate compensation? Conservation demands we take preventive, not reactionary measures.”

_1606900350.jpg) Photo: Bobby Bradley

Photo: Bobby Bradley

The Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), Namibia, is supporting the Indian project committee in cheetah translocation and post-release management. Founder and Director, Dr. Laurie Marker, who visited India in 2010, and again in February 2020, believes that the process will be long and hard, but has potential to make another permanent habitat for the cheetah. “It is very important that enthusiastic and committed rangers and veterinarians be selected for the project. Through proper training, they will become India’s cheetah experts and be central to the success of the project. They will also work with farmers to mitigate conflict,” she says.

Dr. Marker has also drafted an action plan that outlines the logistical steps for cheetah reintroductions. “The animals will first be placed in a one to two hectare, fenced holding area for inspection, where they will be fitted with satellite collars that enable scientists to track their movements and monitor their health status. After a short stay, they will be released into a larger enclosure, to become familiar with their new environment, for two weeks to a month before being released into the sanctuary. Their movements will be monitored by research teams, and if an individual strays too far afield, it will have to be brought back into the sanctuary. The action plan also details instructions on feeding and care, and an assessment of breeding expectations.”

(Read the full interview with Dr.Laurie Marker)

Is the Risk Worthwhile?

Because India is home to other larger cats, the relatively featherweight cheetahs will face competition from leopard and tigers. Cheetahs tend to hunt during the day to avoid competition and kleptoparasitism. Yet 73 per cent of cheetah cub mortality in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania, was found to be a result of predation. A mere five per cent of cubs make it to adulthood. To this, one must add poaching.

To allow the cheetah half-a-chance, there are tall orders to be met: the chosen habitat must have adequate prey, be contiguous with nearby grasslands, enjoy a high degree of protection from poachers, face minimal predator competition and be welcomed by local communities whose livestock may be preyed upon.

Dr. Anish Andheria, President, Wildlife Conservation Trust, says:

“Several aspects need to be considered before the arrival of the animals – ideal cheetah habitats need to be surveyed; human footprint reduced within these areas by offering handsome voluntary relocation packages to communities; alternative grazing lands identified for communities that continue to live in and around these shortlisted sites. And the habitat needs to be revitalised; wild prey populations augmented if necessary; feral dog populations controlled to avoid direct conflict or transfer of unwanted diseases; awareness campaigns to prepare local communities to live alongside cheetahs; and finally, construction of a treatment centre for cheetahs for a soft release programme and to provide seamless care for injured cheetahs, if necessary.”

The Kuno-Palpur National Park in Madhya Pradesh, was identified for cheetah reintroduction, but has been opposed by many who suggest that human-animal conflict would be the undoing of the cat. Initially this forest was prepared for the translocation of the Asiatic lion from the Gir National Park in Gujarat. That proposition remains shelved and now with tigers moving into Kuno-Palpur from Ranthambhore, across the Chambal river, it seems unlikely that cheetahs will ever reach Kuno-Palpur either. Photo: Devavrat Pawar

The road ahead is long and the stakes high. But project proponents believe the monumental risk will be more than worthwhile, for one prime reason – bringing much-needed focus to grasslands and their conservation by using the cheetah as a charismatic ambassador; something that has not been achieved with existing grassland species.

Dr. M.K. Ranjitsinh, a key driving force behind Project Cheetah since the 70s, when he first proposed the idea to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi adds:“Symbols have special significance in India. For Project Tiger, the first nine reserves selected were not only on the basis of the prevalent tiger populations, but mainly to cover the diverse forest habitats of the tiger in the country and the number of critically endangered species which were to be saved therein under the aegis of the tiger. Likewise, bringing back the cheetah is not an end in itself, important though it is, but is also a means to an end: to save something more significant than the cheetah itself – the grasslands of India, the most productive ecosystems of all, along with their dependent species which are critically endangered.”

In Dr. Laurie Marker’s view: “In the effort to reintroduce the cheetah in India, we aim to re-establish its ecosystem function role in representative areas of its former range and contribute to the global effort of conserving the endangered cheetah and preserve its genetic diversity.”

This ambitious proposition does have potential, but there are a lot of ‘ifs’ involved. Success will only be possible if strong grassland policies are created and implemented, if science and conservation take precedence over political and bureaucratic agendas, and if the vigour, budgets and resources remain consistent throughout the coming years. If such a miracle were to materialise, clearly the attempt to bring the cheetah to India might well end up saving the Great Indian Bustard, the Indian wolf and the Lesser Florican together with their much-abused grassland homes.

Cheetah cubs face many threats in their first few months – predation by other big cats, or even jackals and large raptors, disease, and from the illegal pet trade. Less than five per cent survive to adulthood in the wild. Photo: Aditya Dicky Singh.

Genes At Play

Cheetah cubs face many threats in their first few months – predation by other big cats, or even jackals and large raptors, disease, and from the illegal pet trade. Less than five per cent survive to adulthood in the wild. Photo: Aditya Dicky Singh.

Genes At Play

Cheetahs faced two population bottlenecks in the past – first around 100,000 years ago due to rapid range expansion, and second about 10,000 to 12,000 years at the end of the last ice age. This drastically reduced their genetic diversity, and resulted in the physical homogeneity of the species’ current population, making them more susceptible to reduced breeding capacity and increased vulnerability to disease. This along with humancaused pressures puts the species at a great risk of extinction. It is listed as Vulnerable in the IUCN Red List.

There are currently four subspecies of cheetahs in the world – three in Africa and one in Asia. The Asian

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus and Southeast African

Acinonyx jubatus jubatus cheetah diverged approximately 72,000 years ago, according to a recent

study by the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI), and other parties. Asiatic and African subspecies do not exhibit significant morphological and physiological differences. Due to minimal genetic variation, African cheetahs can adapt quite easily to Indian climatic conditions. There have been reports of cheetahs being imported from Africa for the sport of coursing back in the 20

th century, after severe decline in Asiatic populations.

In fact, in his book

Exotic Aliens, renowned wildlife conservationist and author Valmik Thapar theorises that

the cheetah, and the Asiatic lion, were not native to the Indian subcontinent, but were brought in by royalty from Persia and Africa over centuries. He bases this theory on the fact that accounts of these animals strangely don’t appear in historical paintings or texts maintained by royal courts, unlike the well documented encounters with leopards and tigers.

Abinaya Kalyanasundaram is a writer, editor and photographer who loves creating narratives about the natural world. She is Assistant Editor at Sanctuary.

_1606900350.jpg)