South Sentinel - An Andaman Journey

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 22

No. 12,

December 2002

Text and photographs by Pankaj Seksharia

Encounters with a turtle

A strong breeze was blowing in off the sea. Harry and I were fast asleep on the large blue tarpaulin sheet that we weighted down on the beach every night.

It was our fifth day on the island and we were exhausted. Suddenly I felt a tug, like the weights had shifted and the wind was pulling at the tarp under us. I turned to look at Harry, but he was fast asleep. Everything seemed to be in place and I shut my weary eyes again. This time the tarp jerked even harder under me. A touch annoyed, I turned to investigate… and nearly jumped out of ‘bed’. At arm’s length from me, right on top of the tarp, was a huge, female green sea turtle Chelonia mydas, trying desperately to make her way across the tarp that was stuck in her flippers.

I nudged Harry awake and together we quietly moved behind the turtle and gently pulled the tarp out from under her. She then moved a few metres ahead and settled down to dig her nest close to where the other members of our team were still fast asleep. Assured that all was well, we moved our tarp to an adjacent spot and were asleep in no time at all.

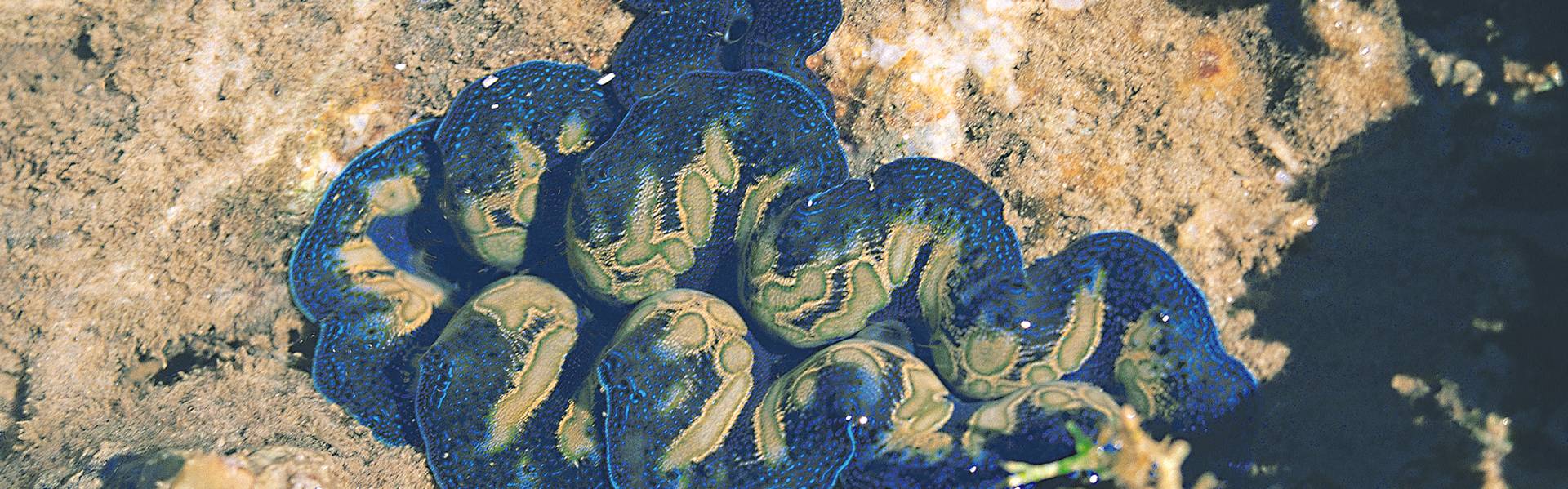

A brilliantly-coloured giant clam provides some idea of the fabled marine diversity of the Andaman Sea.

It was not until the next morning, when we informed them of the drama of the night before, that the others discovered what had happened. Such was the silence and efficiency of the turtle that were it not for us, they might never have known that a green sea turtle had dug her nest only a few feet from where they slept.

It is nearly three years now since that February night on South Sentinel Island, but I still recall my encounter with one of earth’s most ancient life forms vividly. Some of my South Sentinel experiences I recorded in my diary, some I recorded as photographs and many remain as scattered memories. It is a mosaic of these upon which I base this account of a fragile paradise that continues to cry out for protection.

A bird’s eye view of South Sentinel and this ‘sea level’ image together display the island’s three different habitat types: offshore reefs, a fertile inter-tidal zone and dense island rainforests.

The journey to South Sentinel…

We had left for South Sentinel early that morning from Wandoor, near Port Blair. A cool gentle breeze caressed our faces. It was misty and we could just about see another fishing boat on the horizon. The sea was calm and flat, almost glass-like. Looking over, I could actually see the bottom of the ocean bed. Patches of coral flashed by and colourful reef fish swam to and fro. A lone dolphin came swimming up to us. No amount of dolphin watching on television matches the experience of having one dive and swim right next to you. In a fishing boat, you are so close to the dolphin that you can almost reach out and touch it!

The graceful animal surfaced, dived, went to the right and surfaced again. The morning sunlight created abstract, dancing white patterns on its dark body. The cetacean must have stayed with us no more than a few minutes, but the memory of this beautiful creature of the oceans will stay with me forever.

A bird’s eye view of South Sentinel and this ‘sea level’ image together display the island’s three different habitat types: offshore reefs, a fertile inter-tidal zone and dense island rainforests.

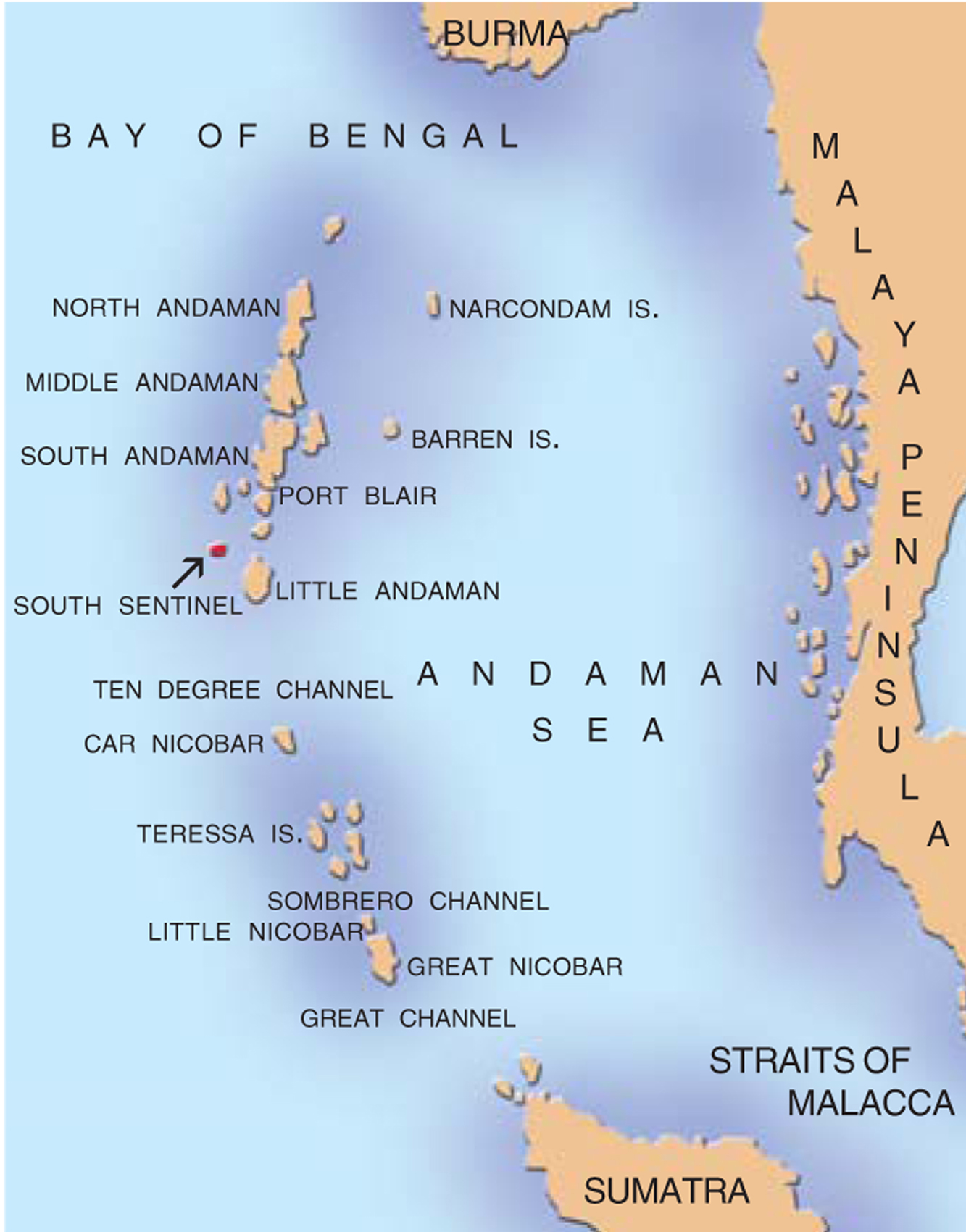

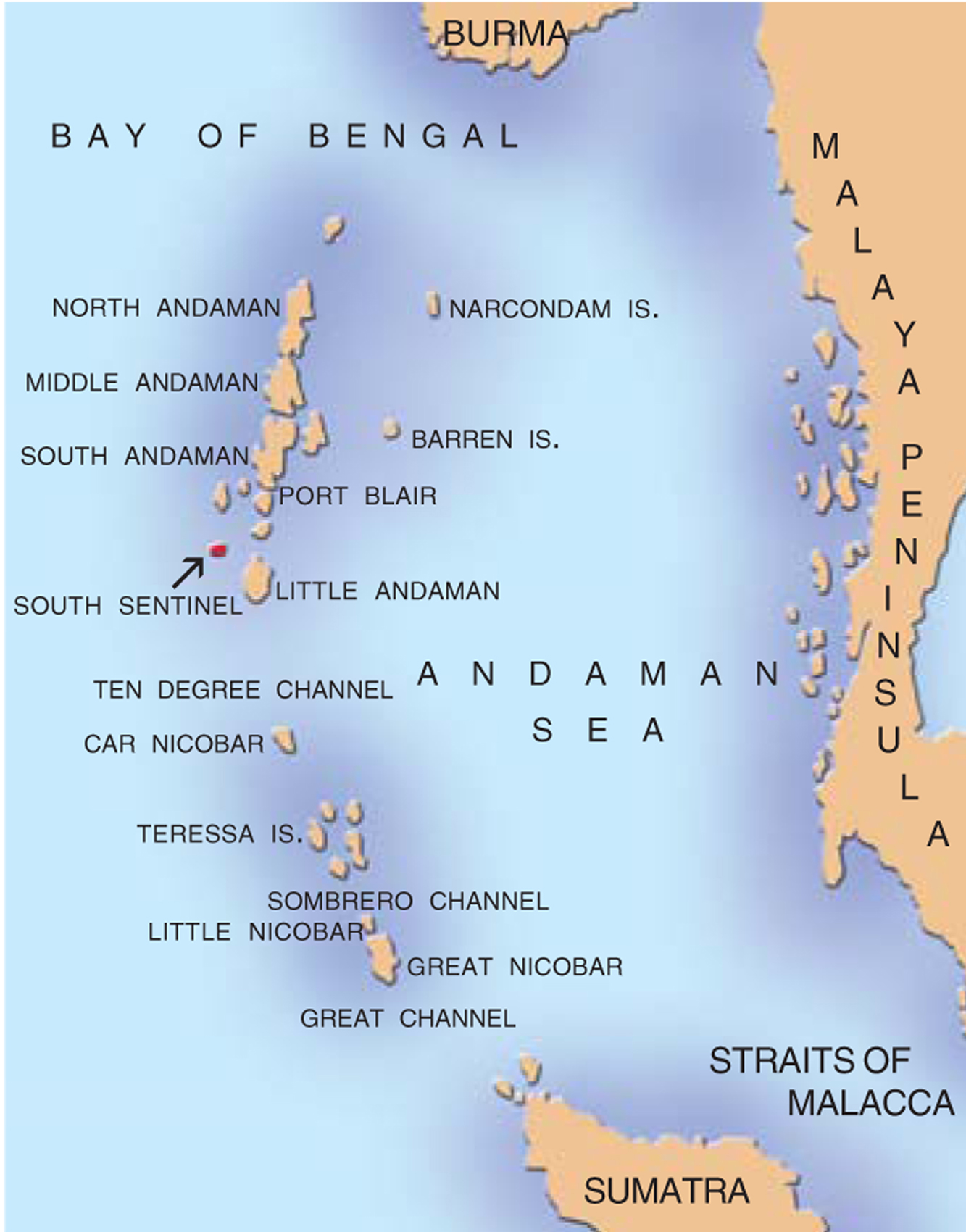

South Sentinel Island

I could hardly believe I was here, on this small (1.61 sq. km.), uninhabited island in the Andaman archipelago in the Bay of Bengal. Just over a six-hour boat ride from Port Blair, I was as close to paradise as I could ever hope to be.

I saw that Davies and Altevogt were right when they were quoted as saying in the Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands: “It’s a flat coral island, where lagoons mark about half the length of the shore, the rest being rocky or sandy. A magnificent sandy beach extends along its northwest coast and the rest of the island is canopied by dense forest trees, lianas and brambles. Forest types include Andamans Tropical Evergreen (approx. 0.75 sq. km.), Littoral Forest (approx. 0.5 sq. km.) and Mangrove Forest or Tidal Swamp Forest (approx. 0.36 sq. km.)”.

There is no fresh water on South Sentinel, so we had to be careful with our stocks. Declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1977, the island is home to some of the most amazing creatures on the planet. Green sea turtles, the beautiful and fragile endemic Andaman day gecko Phelsuma andamanese, the huge yet vulnerable giant robber crabs Birgus latro, the Pied Imperial Pigeon Ducula bicolor nesting in the tree-tops and moray eels and clams, secure amidst a network of coral reefs that surround the island.

The Andamans’ forests are being logged to produce timber and plywood. The resultant erosion is choking mangroves and coral reefs.

A distinguished crew

The very first morning that broke on South Sentinel saw me venture into the rainforest with Uncle Paw, Harry, Rom, Janaki and Alphonse. Uncle Paw is an old member of the Karen community that originally came from Burma, when the British shipped them to the Andamans way back in 1925. Harry Andrews is associated with the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Environment Team (ANET) and conducts crocodile surveys in the island’s mangrove forests. Romulus Whitaker has been visiting and studying the Andaman and Nicobar islands for over two decades. Janaki Lenin is a professional film maker and Alphonse Roy, a wildlife cameraman.

I was in distinguished company and we were here to provide an eye-witness status account of the island’s natural history. We hoped that this would serve as an archival record and possibly as a barrier to those who might seek to harm the island’s ecology in the future. Without baseline data, it is difficult to prove any wrongdoing.

A substantial part of the island, we observed, was covered with littoral forest, with sea mohwa Manilkara littoralis being the dominant tree species. The forest floor was a mosaic of rich black humus and white coral dust, sprinkled with sharp coral pieces. One could easily get cut and just walking on this coral island was an adventure. Fallen trees were strewn everywhere in a tangle of trunks, branches, twigs and leaves. There was dense undergrowth throughout and we had to duck, jump, bend and sway continuously as we walked across the wild island. Uncle Paw, of course, walked barefoot and unconcerned. He was the fastest and most agile of us all. Harry would keep peeping under and into hollow logs, hoping to find a monitor lizard.

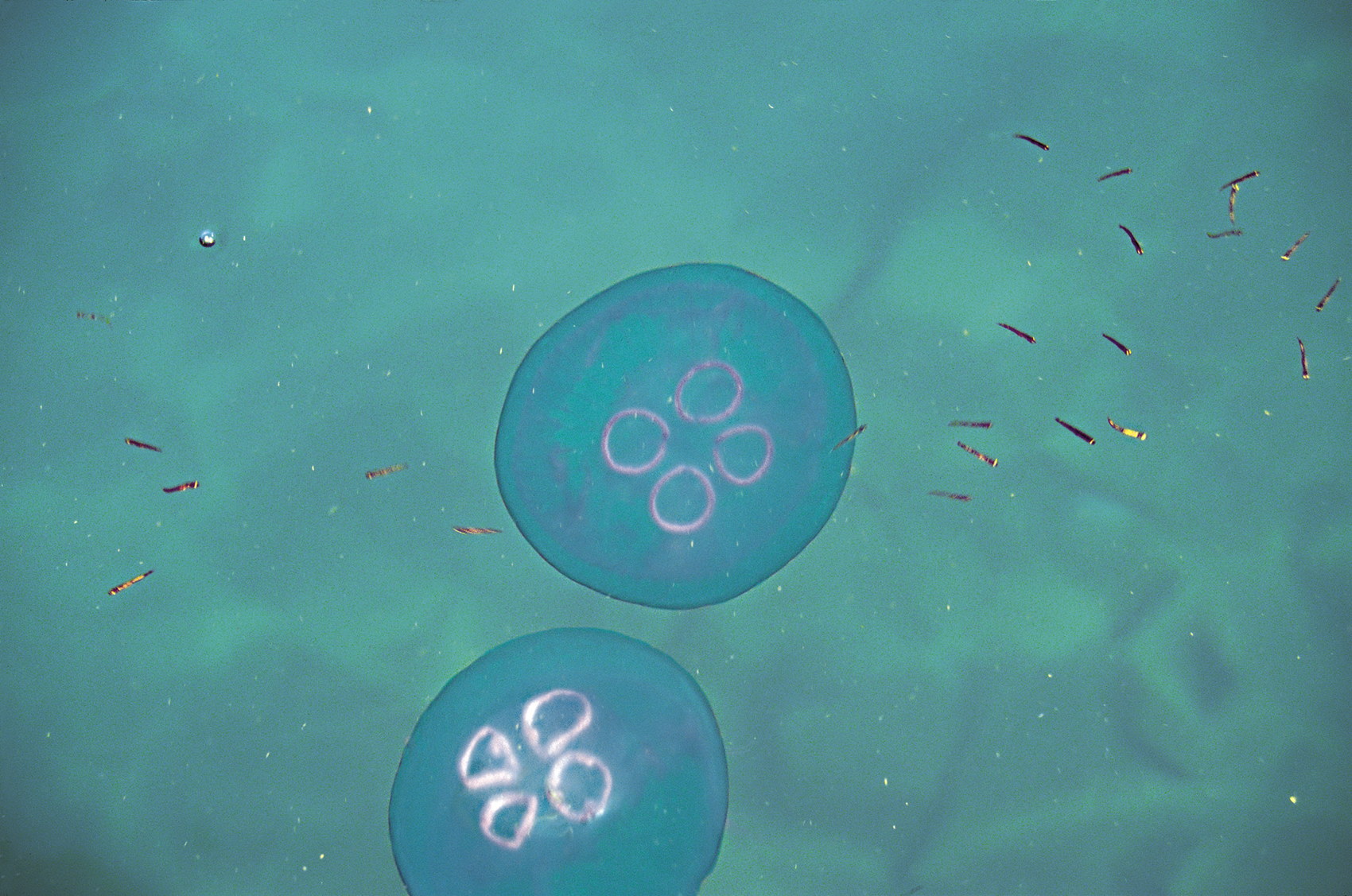

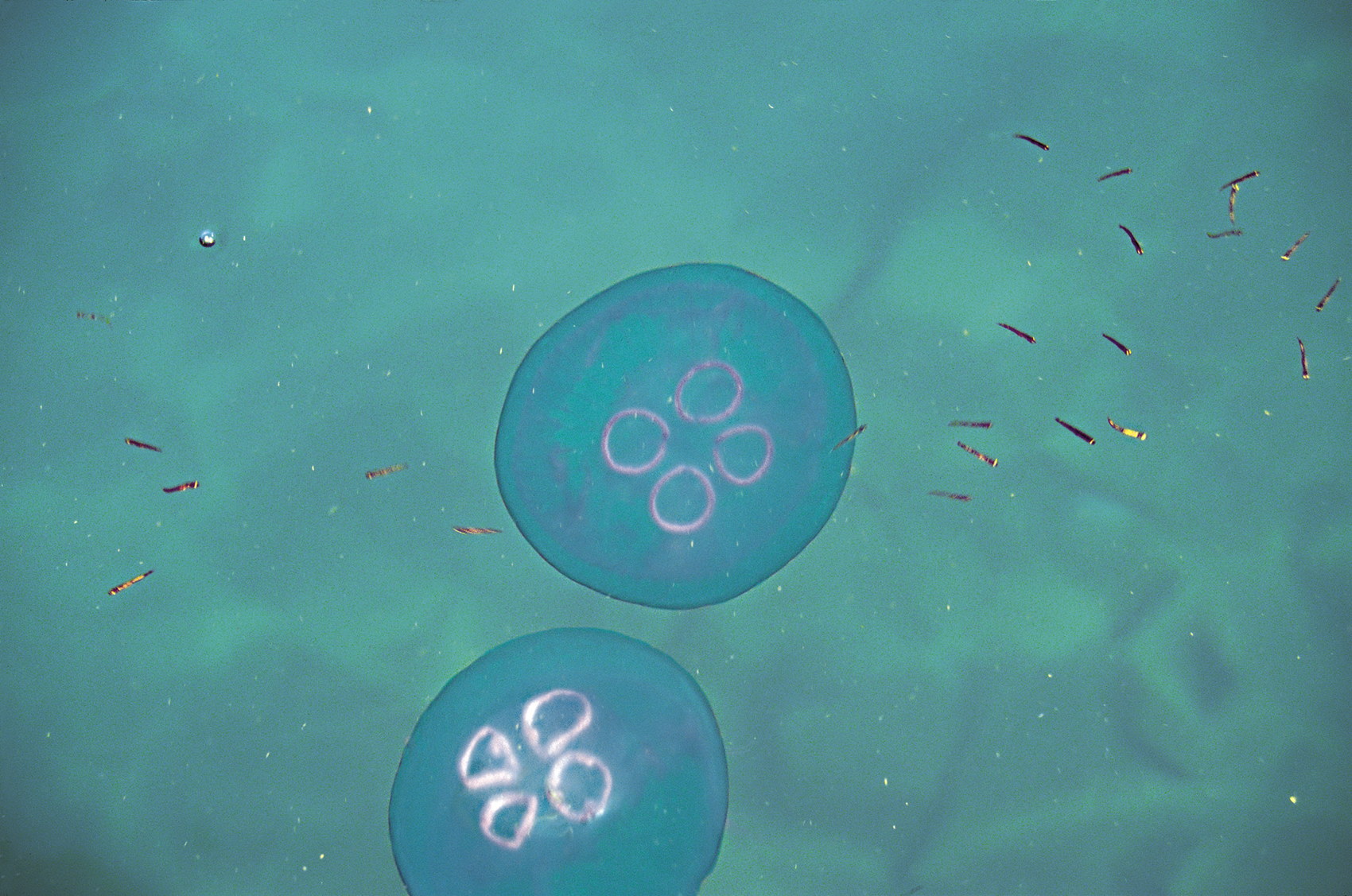

Jellyfish in the coastal waters off South Sentinel represent a vital link in the marine food chain of these relatively pristine tropical islands.

What we saw a lot of, however, was crabs. Too many to count – land crabs, hermit crabs Coenobita sp. and the biggest of them all – the giant robber crabs that virtually ruled the island. With their huge, powerful claws, they are known to easily rip open coconuts to get to the fruit inside. Relatives of the hermit, they have evolved to be so large that they can find no shell large enough in which to take refuge. When threatened, they wave their menacing claws and instinctively withdraw into the dark hollows in the buttresses and roots of the rainforest trees, from where it is well nigh impossible to extricate them.

As we walked through the forest, the sweet calls of birds filled the forest air, beautiful dappled light danced in clearings, creating a mosaic of light and shadow. Here and there, marshy depressions, wet and sinky, gave the area a prehistoric feel. We felt like intruders in an ancient world. Fascinated, we would stop frequently to photograph crabs or just savour the ambience. Uncle Paw, meanwhile, would sit on a fallen trunk with an amused look on his face – seemingly unconcerned, though deeply interested in what we were doing – a bottle of water in his hand and a bidi dangling from his lips.

A green sea turtle returns to the sea after laying its eggs along one of South Sentinel’s undisturbed beaches.

Money matters

After an eventful day, I slept a dreamless sleep and awoke the next morning to exquisite surrounds. Rummaging through my waist pouch I found writing pens, a matchbox, rubber bands, visiting cards, notepads, a Swiss army knife, spectacles, voter identity card, wrist-watch, the key to a lock I didn’t have and money… lots of it, considering that I had no way to spend it on Sentinel. I had jettisoned my driver’s license and address books at Port Blair, but I held on to my voter’s identity card in case a Coast Guard patrol wanted me to prove my bonafides.

But money? Why would I have brought money to this isolated haven? I asked myself. Its amazing the kind of security certain things give us. Money falls in that category. I was simply unable to leave it behind, though it was probably completely useless in a place like this!

But there was the proverbial little twist to this tale. A day after we landed on the island, Harry asked Rom if he was carrying money. ‘Money! Here?’ Everybody jumped. Why do you need money here was the question on all our faces. “For high sea trade,” said Harry seriously. “If we see a fishing boat go by, I want to buy some fish.” He wasn’t kidding. Money, obviously has its uses everywhere!

Giant robber crabs, protected by their sheer size, have virtually taken over this tiny Indian Ocean paradise.

A view from above

At one end of the island is a tall iron lighthouse, soaring above the rainforest. Its solar powered light starts blinking with the coming of dusk. I clambered to the top of the tower and marvelled at the awesome panorama: the green carpet of the forest canopy, rimmed by white strips of sand and engulfed in the unending blues of the Andaman Sea. It was a typical White-bellied Sea Eagle’s eye view of the world, and it was impressive. A lone pair of these magnificent birds had established their dominion over the island and its surrounding waters. In our entire stay on the island, we did not see a third White-bellied Sea Eagle and this seemed as good an indication as any of the territorial range of a pair of sea eagles.

Fragile heritage: The Jarawas lived in perfect harmony with their environment for centuries, but face extinction after meeting the modern world whose ‘do-gooders’ have shattered their tranquillity.

More about sea turtles

I loved the tower, but sadly I was only able to scan the island from this perch twice. From here, our camp looked like a little toy set-up. I could see numerous turtle tracks cutting across the entire length of the beach, one no doubt left by the nesting female I had seen the previous night. I spent many hours every night walking the beach, hoping to see green sea turtles as they came out to nest. I was lucky. I managed to see three to four turtles haul themselves up the beach under the cover of darkness every night, laboriously dig their nest, lay their eggs and return to sea. Why did we not see any other turtle species nest here? According to Harry, olive Ridleys Lepidochelys olivacea need much wider stretches of sand and the massive leatherbacks Dermochelya coriacea avoid the rocky or reefy patches that abound at South Sentinel.

Sea turtles are among the most magnificent creatures imaginable. Globally threatened, they are killed for meat and their shells. Their eggs are consumed as food and because they are mistakenly believed to have aphrodisiacal properties. Dredgers often kill turtles and they are regularly run over by leisure boats, poisoned by pollution, strangled by trash and drowned by nets and fishing lines. The beaches on which they nest (like many in the A&N islands) are mined for sand, destroying them forever. All this is in addition to the many natural threats turtles must face in their battle to survive. It is estimated that less than one per cent of the eggs laid by turtles survive to adulthood, and these slim odds are being made slimmer by humans.

A hermit crab feeding on a dead green sea turtle hatchling washed up on the shore.

Anybody who has seen turtles, either swimming in the sea or nesting on the beach, will agree that they are one of nature’s loveliest creatures. I remember feeling humbled and grateful one night for the privilege of watching one of those ‘Greens’ go about her job of nesting in the dark silence of the South Sentinel night. I feel more than a little guilty about my inability to prevent their massacre at the hands of Homo sapiens.

MAP NOT TO SCALE

The rhythm of the tides

South Sentinel is an amazing island in more ways than one. Bang in the middle is the small, shallow marsh that I mentioned earlier. The first time we saw it, it was full of water, and there were a large number of giant robber crabs all over the place. Only hours later, however, the edges were drying up and there was just a remnant puddle in the middle. Following the logical scheme of things, I expected to find a dry marsh bed on my next visit. To my utter surprise, I saw that it was more flooded than ever. There was no stream emptying into the marsh and not a drop of rain had fallen since we had been on the island! Baffled and fascinated, I eventually worked it out. The level of water in this marsh in the middle of this island was dependant on the rise and fall of the sea tide! The porous nature of the coral island permitted the sea water to rise, filling the marsh and subsequently draining it when the tide fell!

South Sentinel is just a speck in the beautiful and fragile Andaman and Nicobar archipelago. The islands, on the whole, are still in good shape, but things are changing fast. A population explosion is taking place. Not because of mass births, but because of large-scale migration from the mainland by official (misguided) policy that is straining the islands’ carrying capacity. What is more, virgin, evergreen forests are being rapidly logged to produce timber and plywood. The resultant erosion is choking mangroves and coral reefs. And the oceans are getting more polluted every day. The islands’ original inhabitants, tribes like the Onge and Jarawa, have been virtually wiped out because of the destruction of their habitat and exposure to alien diseases… the list is depressingly long.

The image may look aesthetic, but it represents the dark side of an Andaman tragedy. This fire was lit by settlers to clear forests in Wandoor, 25 km. from Port Blair. Mainlanders are officially encouraged to migrate to the islands.

For now however, I have my blinkers on, looking only at South Sentinel. Thanks to its remoteness, it is still as inaccessible and pristine as one could hope for. Life still flourishes here in all its untainted glory; green sea turtles still crawl out of the ocean to lay their eggs as they have for millions of years; White-bellied Sea Eagles still soar majestically over the green canopy; and the marsh in the middle of the island still follows the rhythm of the tides. Nature is in command here, and all seems well with the world!

The Andaman Trunk Road at the point where it enters the Jarawa Reserve. The road has destabilised the ecological security of the Jarawas, exposed them to alien diseases and encouraged illegal logging.

Andaman Trunk Road: A Road to Despair

The Andaman Trunk Road at the point where it enters the Jarawa Reserve. The road has destabilised the ecological security of the Jarawas, exposed them to alien diseases and encouraged illegal logging.

Andaman Trunk Road: A Road to Despair

The Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) connects Port Blair in South Andaman to Diglipur in the North, covering a distance of roughly 340 km. This road is responsible for the destruction of large tracts of virgin evergreen forests and has had severe adverse impact on the original inhabitants of the forests, the Jarawa tribe. Construction of the road started in 1971 and from the very beginning, the Jarawas had opposed it because they feared its impact on their way of life. The protests against the road from environmentalists, anthropologists and the Jarawas themselves were ignored, and the situation escalated into violence, with attacks and counter-attacks on both sides.

The work has been completed but there are now plans to double-lane the road, which has cut through the heart of the Jarawa tribe’s forest home. It has also facilitated the movement of settlers from mainland India into these forests and surrounding areas, increasing manifold the possibility of interaction and conflict between settlers and the Jarawas. It is also one of the main causes for a devastating measles epidemic that recently affected the Jarawa community, resulting in several deaths.

Huge amounts of money (over 15 crores) and timber are used annually to maintain the road. The Society for Andaman & Nicobar Ecology (SANE) estimates this consumes a minimum of 12,000 cu.m. of timber from the evergreen forests. Compare this with the 80,000 cu.m. of timber that is officially logged from these islands annually and one gets a sense of the destruction being caused by the ATR. The ATR is a perfect example of shortsighted planning, as it is not even the best way to travel in the Andamans. The traditional inhabitants of these islands have always used the sea route. When all the towns in the Andamans are located on the coast, it makes no sense to cut through the heart of the forest.