S.P. Shahi - (1917-1986)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 31

No. 2,

February 2011

By Bittu Sahgal

An unlikely wildlifer, the late S.P. Shahi retired as the Chief Wildlife Warden of Bihar and was one of the architects of the great wildlife resurrection of the 1970s and 1980s when most of the parks and sanctuaries we see today were selected, notified and nursed back to health. A ‘wolf man’, he evolved to become one of Project Tiger’s most holistic thinkers. He was an ardent wildlife photographer and one of Bihar’s best known wildlife defenders. His book Backs to the Wall – A Saga of Wildlife in Bihar, published in 1977, remains one of the most comprehensive archival records of the vanishing wildlife of Bihar.

Standing on the balcony of our sea-facing home in Mumbai, soon after he retired as the Chief Wildlife Warden of Bihar, S.P. Shahi said to me: “There are sharks swimming out there… they are the wolves of the sea. I wish I could study them also. They too are being persecuted by us, just like the wolves."

It was the measure of the man that his personal horizon was wide and distant enough to encompass all living creatures, not just the tigers, leopards and wolves he had come to be associated with after a lifetime spent in the Indian jungle.

A product of his time, Shahi was trained by the British who then considered trees to be worth no more than the amount their timber fetched. And wild animals, he was taught, had no greater value than their pelts, ivory, horns, or the ‘sport they offered to hunters. When narrating stories of his earlier life to me, of trees felled and tigers shot, his eyes would mist over: “I wish someone had introduced me to the joys of the camera earlier."

Photo Courtesy:P.K. Sen

I miss S.P. Shahi and his childlike enthusiasm for wildlife and his intense curiosity that kept him on an eternal hunt for answers to questions such as the power balance between tigers, dholes and wolves, or predator-prey relationships involving frogs, fish and mosquito larvae (came up after Sanctuary published an article on frogs).

After a stint at the Indian Forest College in Dehradun between 1940 and 1942, S.P. Shahi found himself attached to the Bihar Forest Service where he went about the business of ‘silviculture forestry with vigour, fully convinced that sambar, chital and wild pigs were mere pests that destroyed the commercial nurseries that officers like him set up. Over lunch one day, I recall him saying: “I actually believed that since herbivores ate sal seeds the trees would die out! We were totally brainwashed into believing that man-made plantations were better than natural forests."

P.K. Sen, former Director of Project Tiger, who knew Shahi well, says: “S.P. Shahis work in Palamau and his meticulous documentation of its wildlife was a very key reason that this forest was chosen as one of the first nine to be declared as tiger reserves in 1973. Few people realise that as far back as 1968 he had all shooting blocks in the state of Bihar cancelled, two years before the Government of India took this step in 1970. What triggered this determination was the remorse he felt when he himself shot a tigress and was haunted by the senselessness of the act."

Not surprisingly, after realisation struck, he was like a man possessed. Having given up the gun for the camera he began to spend extraordinary amounts of time in the wilds of his beloved Bihar, often spending night after night in make-shift hides, waiting for a chance to photograph a wolf or tiger. He also rededicated his life to the proposition that new, young forest officers should not be contaminated by faulty learning that placed nature at a discount. Towards this end he published articles, scientific papers and proceeded to give lecture after lecture in an effort to wean future decision makers away from the ecological quick sands of the past.

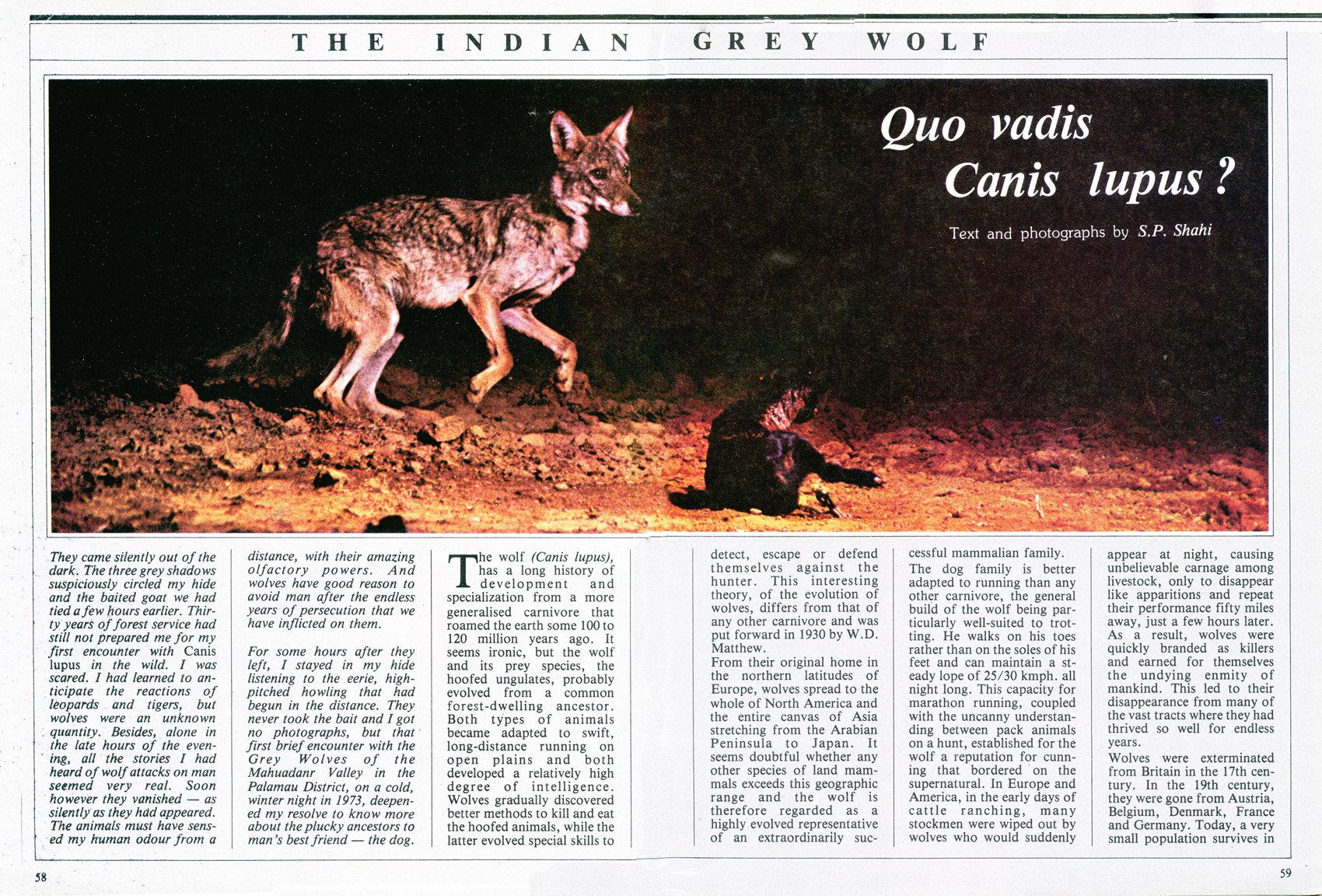

This opening double spread image was printed in the 1982 issue of Sanctuary Asia. S.P. Shahi, meticulous to a fault, spent two weeks working with the Editor on the article.

Photo:S.P. Shahi

At first it seemed that the efforts of individuals such as S.P. Shahi, Kailash Sankhala, S. Deb Roy, Fateh Singh Rathore and other pioneers would be of no avail. The “cut the trees for revenue" psyche of the Indian Forest Service seemed just too strong and the resistance from them to stop timber operations was tremendous. But persistence paid off. The cessation of timber and other commercial operations and enhanced protection restored peace to the jungle… and tigers began to flourish.

About S.P. Shahi, P.K Sen says with admiration that can scarcely be concealed: “Of the very few Indian stalwarts, I would rate him as one of the five top most wildlife experts of his time. Even years after his retirement and despite failing health, I have seen him rise at three a.m and work until seven p.m., equipped with little other than a packed lunch and his trusty camera."

His love for wildlife photography is what first drew him to Sanctuary. In time, he took to using the magazine to communicate the rationale of ecological thinking - leave nature to itself and it will fix the problems that man has caused - to forest officials, policy makers and the general public.

Hunters en route to the top of the Dalma hill to worship the Dalma deity. Such traditional hunts have been stopped.

Photo:S.P. Shahi

Of course, by the time I met S.P. Shahi, he was already a “name". His work on wolves was being quoted far and wide and almost for the first time in India Canis lupus was placed on a pedestal instead of being written off as ‘vermin. Life was slower then, in the 1980s, and he and I actually sat together for two weeks researching, discussing and editing his detailed field observations on wolves to finalise an article titled Quo vadis, Canis lupus? for the January-March 1982 issue of Sanctuary. In it he wrote:

They came silently out of the dark. The three grey shadows suspiciously circled my hide and the baited goat we had tied a few hours earlier. Thirty years of forest service had still not prepared me for my first encounter with Canis lupus in the wild. I was scared. I had learned to anticipate the reactions of leopards and tigers, but wolves were an unknown quantity. Besides, alone in the late hours of the evening, all the stories I had heard of wolf attacks on man seemed very real. Soon however they vanished - as silently as they had appeared. The animals must have sensed my human odour from a distance, with their amazing olfactory powers. And wolves have good reason to avoid man after the endless years of persecution that we have inflicted on them.

For some hours after they left, I stayed in my hide listening to the eerie, high-pitched howling that had begun in the distance. They never took the bait and I got no photographs, but that first brief encounter with the grey wolves of the Mahuadanr Valley in the Palamau District, on a cold, winter night in 1973, deepened my resolve to know more about the plucky ancestors to mans best friend - the dog.

The author's rough sketch of his hide and bait set up to photograph a tiger.

Photo:S.P. Shahi

I find myself reading such old writings more and more these days and wonder if they will ever make them like S.P. Shahi again?