Roadside Tigers in the United States

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 7,

July 2020

By Sarika Khanwilkar

The Tiger Truck Stop

Red letters flashed “live” on a sign above the gas station. Petrol fumes overwhelmed me as I stepped out of the car while the whirr of vehicles traveling east on a Louisiana highway hummed constantly in the background. I walked towards the metal fencing, knowing that a tiger might be inside, but hoping that nothing would be there.

The Tiger Truck Stop in Louisiana state, southern United States. Photo: Sarika Khanwilkar.

In an anticlimactic yet life-changing moment, I saw a live tiger as promised by the sign. I had seen tigers in zoos, and in the bamboo thickets and sal forests of central India’s tiger reserves, but I never imagined I would see a tiger at a gas station on the side of an American highway. Similar to previous tiger sightings, it was a moment I will never forget. But unlike previous sightings, this moment at the Tiger Truck Stop was filled with discomfort and bewilderment.

_1594382601.jpg)

Tony, the tiger at the Tiger Truck Stop. Photo: Sarika Khanwilkar.

After I discovered the Tiger Truck Stop, I learned that tigers, although endangered and disappearing from many of their wild habitats, were somehow persisting in metal cages. Ironically, after decades of global tiger conservation efforts, captivity in foreign lands was the one place where tiger populations were undoubtedly increasing.

Roadside zoos

There are an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 tigers in the United States of America (U.S.), more than double the number of tigers found in India. Estimates for the number of captive tigers are so large because there is no nationwide oversight of captive tigers. Most U.S. captive tigers are found in backyards as pets or in “roadside zoos” such as the Tiger Truck Stop.

Roadside zoos are privately owned commercial operations that exhibit and breed tigers for tourists, and equate saving tigers to breeding them. For example, on Tiger Truck Stop’s website, they boast that “more tiger cubs have been born at our truck stop than in any zoo in the US!” Yet, tiger breeding in authorised zoos, which are legitimate non-profit conservation organizations, is fundamentally different from tiger breeding at roadside zoos.

Zoos contribute money to protect tigers in wild places and produce scientific knowledge. Meanwhile, tigers in roadside zoos are bred entirely for tourism. Tigers in roadside zoos are generic tigers, meaning they are not of a particular subspecies. For example, a generic tiger might be a mix between a Bengal tiger found in India and a Siberian tiger found in Russia. In addition, tigers are commonly bred with lions to produce ligers or tigons, which are unnatural hybrid species. Furthermore, none of the profits from roadside zoos go towards tiger conservation efforts in the wild. Although I didn’t pay anything to see the tiger at the Tiger Truck Stop, additional on-site facilities such as the ‘24-hour Tiger Cafe’ and gift shop create revenue from visitors who are genuinely convinced that roadside tiger exhibits are good for wild tigers. By misrepresenting their work as conservation, roadside zoos displace money from legitimate tiger conservation efforts.

Roadside zoos are incentivised to continually breed tigers because a tiger between the ages of eight and 12 weeks old is legally permitted to interact with the public, and cub petting generates most of the revenue needed to stay operational. Legitimate zoos do not allow cub petting. Once tigers get too old for cub petting they are an enormous expense. At this age, a tiger may be sold to a private household, exhibited to the public behind a cage, or even killed. Many US states lack laws specific to the disposal of dead tigers and we do not know where these unwanted and unprofitable tigers go.

Cub petting allows tourists to get up close with young tigers. Photo: Steve Winter/National Geographic.

Captive tigers in the illegal trade

What happens to tigers when they die is important because of the high value of tiger parts, such as skin, bones, and claws, on the illegal wildlife market. Seizures of illegally traded tiger parts around the world have increased since 2002 and the demand for tiger parts drives poaching, which is one of the primary threats to the survival of wild tigers. Captive tigers from the US could be supplying parts to this burgeoning illegal market and driving demand. As recently as 2018, a man was sentenced to prison for selling and sending tiger skulls purchased in the US to Thailand.

Bittu Sahgal, the founder of Sanctuary Asia and Sanctuary Nature Foundation, explains that “captive-bred tigers in the US are mostly held in commercial operations and are not valuable to conservation. Tigers bred in the US that enter the illegal trade could be stimulating the poaching of wild tigers from India.” Indeed, captive tigers around the world provide parts to satisfy illegal demand and encourage poaching.

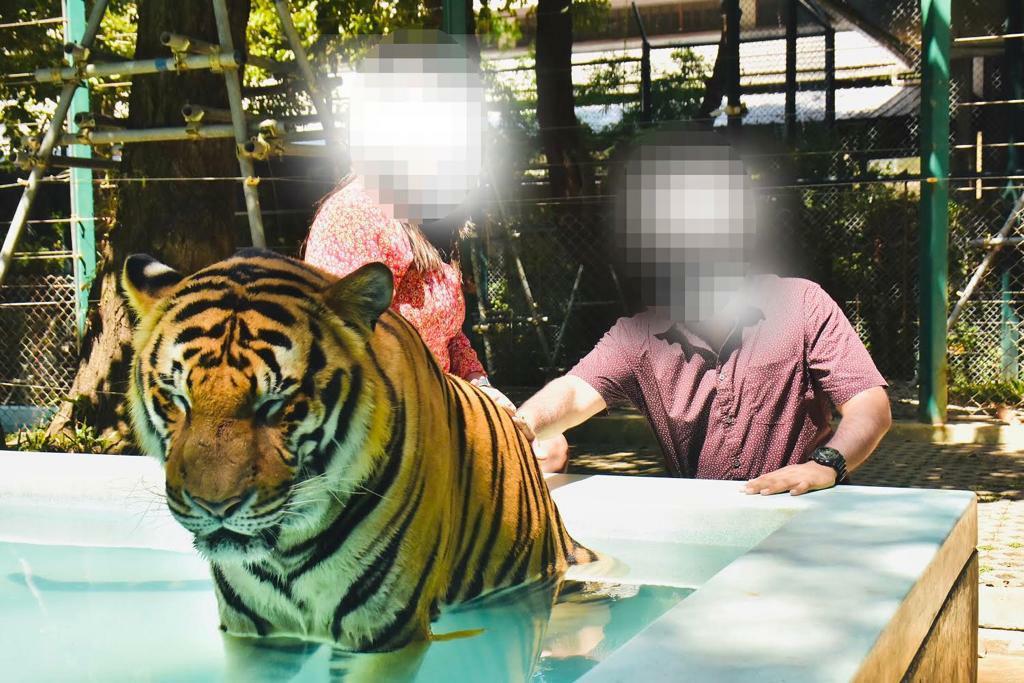

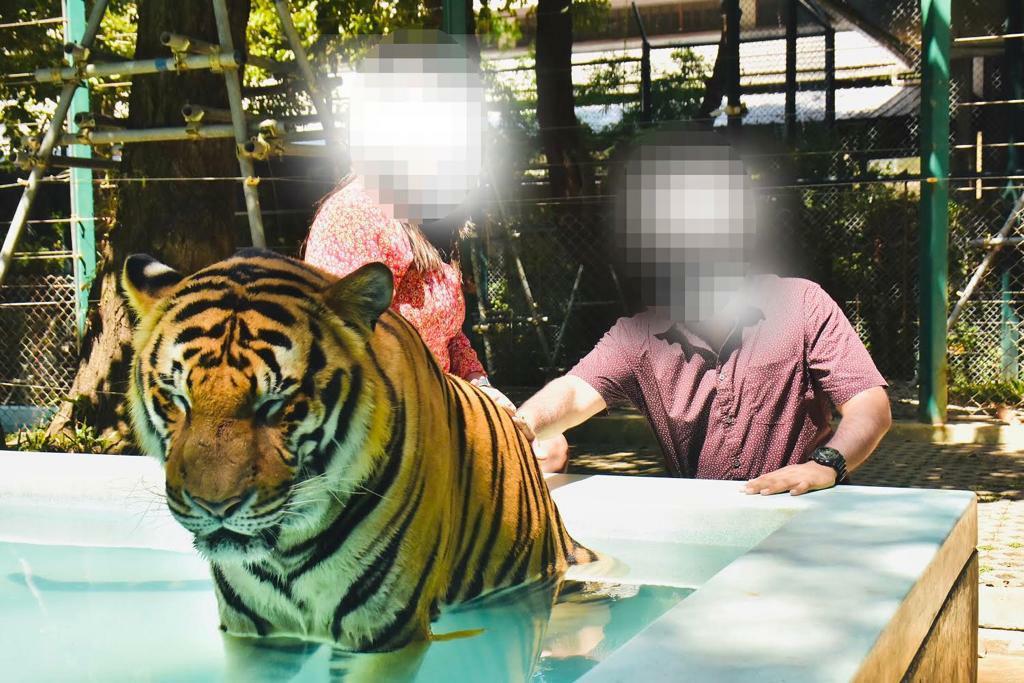

Tourists interacting with a captive tiger at a commercial operation in Thailand. Photo: Anonymous, used with permission.

Tourists interacting with a captive tiger at a commercial operation in Thailand. Photo: Anonymous, used with permission.

In addition to the U.S., tigers are held in commercial operations and intensively bred in farms in China, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and South Africa. Captive tigers in each of these countries are known to have supplied the illegal demand for tiger parts.

Petition against roadside zoos

Our time to move from awareness to action on the issue of tigers in captivity is now, because wild tigers, India’s national animal, do not have the luxury of time. The Big Cat Public Safety Act is a bill that will ban pet tiger ownership and cub petting in the US. If adopted as a law, it will essentially make it impossible for roadside zoos to operate. Putting an end to pet tigers and roadside zoos in the U.S. will create momentum for addressing captive tiger issues around the world.

Take action in support of the Big Cat Public Safety Act. Sign the petition, ‘Indians against the illegitimate breeding and ownership of tigers in the US,’ which I will present to lawmakers in Washington D.C. before the bill is voted on. For years, leaders in pushing the legislation forward were members of the Big Cat Sanctuary Alliance, including the International Fund for Animal Welfare and other U.S.-based animal sanctuaries. Until now, the voices of people from India were absent from discussions about captive tigers in the US. Bittu adds, “It is important that people from India show their support for the Big Cat Public Safety Act by signing this online petition." People from India have a right to be heard on issues related to commercial breeding of tigers.

Indians can take action to address the captive tiger problem in the US by signing the online petition. Photo: Designed by Sarika Khanwilkar.

Indians can take action to address the captive tiger problem in the US by signing the online petition. Photo: Designed by Sarika Khanwilkar.

Sign the petition today and join the campaign by sharing it on social media with #TigersInAmerica.

Sarika Khanwilkar is a Ph.D. researcher at Columbia University, Fulbright alumni, and founder of Wild Tiger, a US-based non-profit organisation. She has spent the last two years researching the relationship between captive tigers in the US, wild tigers, and the illegal trade in tiger parts.

_1594382601.jpg)