Rewilding What Has Always Been Wild Sri Lankan Restoration Stories

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 10,

October 2023

Text, Images and Cartography by Ian Lockwood

I’m climbing up a weathered granite hillock that emerges from a riot of verdant, dry-evergreen jungle growth in a remote corner of Sri Lanka. My family is up ahead and I pause to take in the landscape and watch a Crested Serpent Eagle circling above us. Across pockets of forest and a few abandoned rice fields and salt estuaries, shimmers the Indian Ocean. Under a warm October sun, the sky is a deep blue with high, wispy clouds. A cacophony of dry zone bird songs emanates from the forest. Soon, the North East monsoon will bring its seasonal nourishment to this part of the island, but at the moment the landscape seems parched. Up ahead on the summit of this hillock are the crumbling remains of a 2,000 year-old Buddhist dagoba. Archaeological sites like these often include beautifully-carved figures of wild creatures – elephants, lions, and horses – reminding us of an age-old relationship between humans and wildlife. In fact, we are on the boundary of a large Protected Area – the Yala-Kumana complex – but there are no divisions or clear boundaries between the wilderness and anthropogenic landscapes. This is the situation in much of Sri Lanka, where wild and human landscapes intermingle and are difficult to demarcate. It’s a fine place to contemplate ideas of wilderness, rewilding, and restoration in the Sri Lankan context.

In an age of rapid human population growth, consumerism, resource exploitation and human-induced climate change, notions of wild or wilderness are timely. News of environmental degradation of marine and terrestrial ecosystems owing to out-of-control forest fires, Amazonian deforestation and plastic pollution can be overwhelming. The idea of rewilding is a relatively new concept and a timely, important strategy that seeks to address these challenges.

-1200_1696570346.jpg)

The World Heritage Site of Sinharaja in south-western Sri Lanka has been the site of several important ecological restoration efforts. The boundary, as seen in this image, is composed of a mix of small plots, tea cultivation, timber plantations and mixed forests.

Wild’ And Wilderness In Sri Lanka

The notion of ‘wild’ as something separate from our normal human landscapes is somewhat alien in Sri Lanka and the wider South Asian context. ‘Wild’ suggests a landscape or area free of Homo sapiens and all the inglorious impacts of our species. In response to human-dominated landscapes, major efforts are underway to rewild landscapes in Europe and other parts of the world. In an important article in Conservation Biology, the authors present a “continuum of wilderness” stretching from urban to wilderness. Rewilding, a step along the continuum, is “the science-based restoration of self-regulating ecosystems and to a transformation in human–nature relationships” (Soulé, 1995, and Carter et al., 2021).

Where Sri Lanka sits is not clear and its position on the continuum is complicated because of the degree that Sri Lanka’s ancient civilisations have been closely intertwined with natural systems and cycles. Some of the country’s most-visited protected wilderness areas were previously the sites of sophisticated ancient ‘hydrologic civilisations’. These early human communities were genius water engineers who learned to preserve torrential monsoon rains in tank systems that sustained them far into the long dry season. The Yala-Kumana complex hosted the Ruhuna civilisation, which was in existence as early as 2,000 BCE. Wilpattu National Park, home to some of the finest dry zone forest ecosystems and one of the first national parks in Sri Lanka, has ruins of some of the earliest human visitors to Sri Lanka. The Peak Wilderness Protected Area in the Central Highlands hosts an annual, crowded human pilgrimage season, and yet is renowned for its biodiversity. New discoveries of amphibians and ongoing studies of the movement of leopards in and out of the Peak Wilderness Protected Area make it one the most exciting places for conservation biologists.

CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT Saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus in Colombo’s Weli Park, an urban wetland that shows clear evidence of unintentional rewilding in the heart of Sri Lanka’s capital city. Seeds of Cullenia ceylanica, an endemic late successional lowland rainforest species that will only establish itself once restoration is well underway. Lyre-nosed lizard Lyriocephalus scutatus, a flamboyant Sri Lankan endemic that the author found in a degraded set-zone forest undergoing succession and restoration. Pinus caribaea plantation being overtaken by site-specific native species in the successful trial plot set up by Professor Nimal Gunatilleke and others on the north-west edge of Sinharaja. Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni at a day roost in recovering plantation/secondary forest outside of the Sinharaja core zone. Winged seed of Dipterocarpus zeylanicus, one of the late-successional species that is widely planted in restoration plots in the Sinharaja area. Leaf insect (most likely Phyllium bioculatum) found in restored and recovering semi-evergreen forest in the Dy Zone near Popham’s Arboretum.

Modern Crisis In The Land Of Serendipity

Regardless of its rich history of human-wildlife coexistence, there is little doubt that there is a crisis with humans and their wild neighbours in 21st Century Sri Lanka. Agricultural expansion, urban growth and other changes have put pressure on large mammals. There are few weeks that pass without news of an elephant being electrocuted or a poor farmer’s homestead being vandalised by pachyderms. Tea workers in the Central Highlands are encountering leopards more frequently. Photographs of elephants rummaging in piles of mixed waste in the Cultural Triangle have shocked audiences in Sri Lanka and around the world. The modern approach, influenced by experiences elsewhere, has been to dig trenches and install electric fences around wilderness areas.

Since Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948, there has been a significant loss of forest cover: the Forest Department estimates Sri Lanka’s 45 per cent forest cover in the mid-1950s is down to less than 30 per cent cover today, and human impact has spread with a population that is now 22 million strong. Large-scale plantations of non-native timber species, which were encouraged several decades ago, now distort these forest cover numbers. The impact of the bloody civil war between 1983 and 2009 on natural systems has yet to be fully studied. Some areas suffered significant scarring while parts, such as the Vanni (the mainland area of Sri Lanka’s northern province), were depopulated and forest cover increased. The future of northern forest areas is not secure as some see this as an opportunity to develop shrimp farms, timber, mining, and other extractive industries.

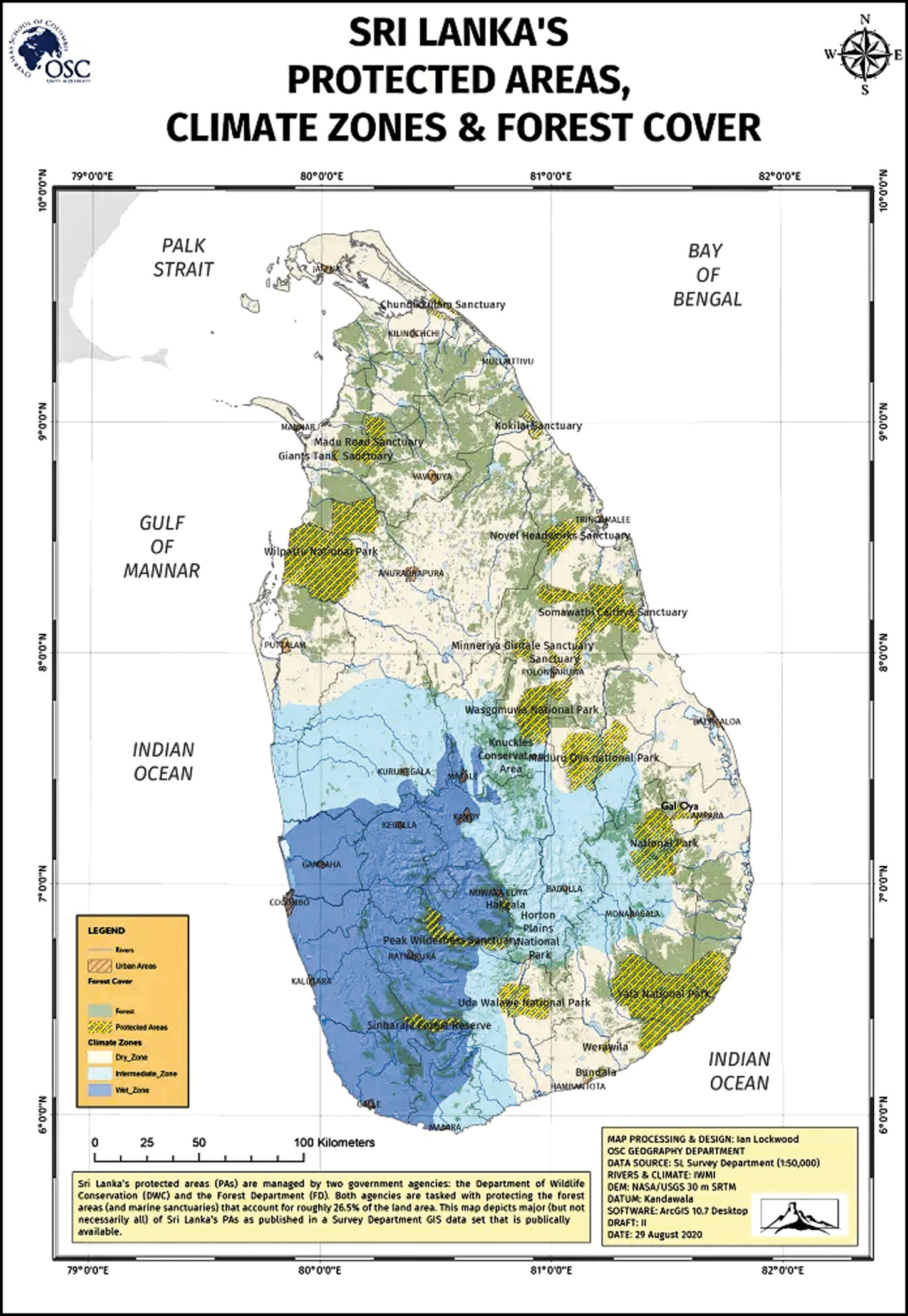

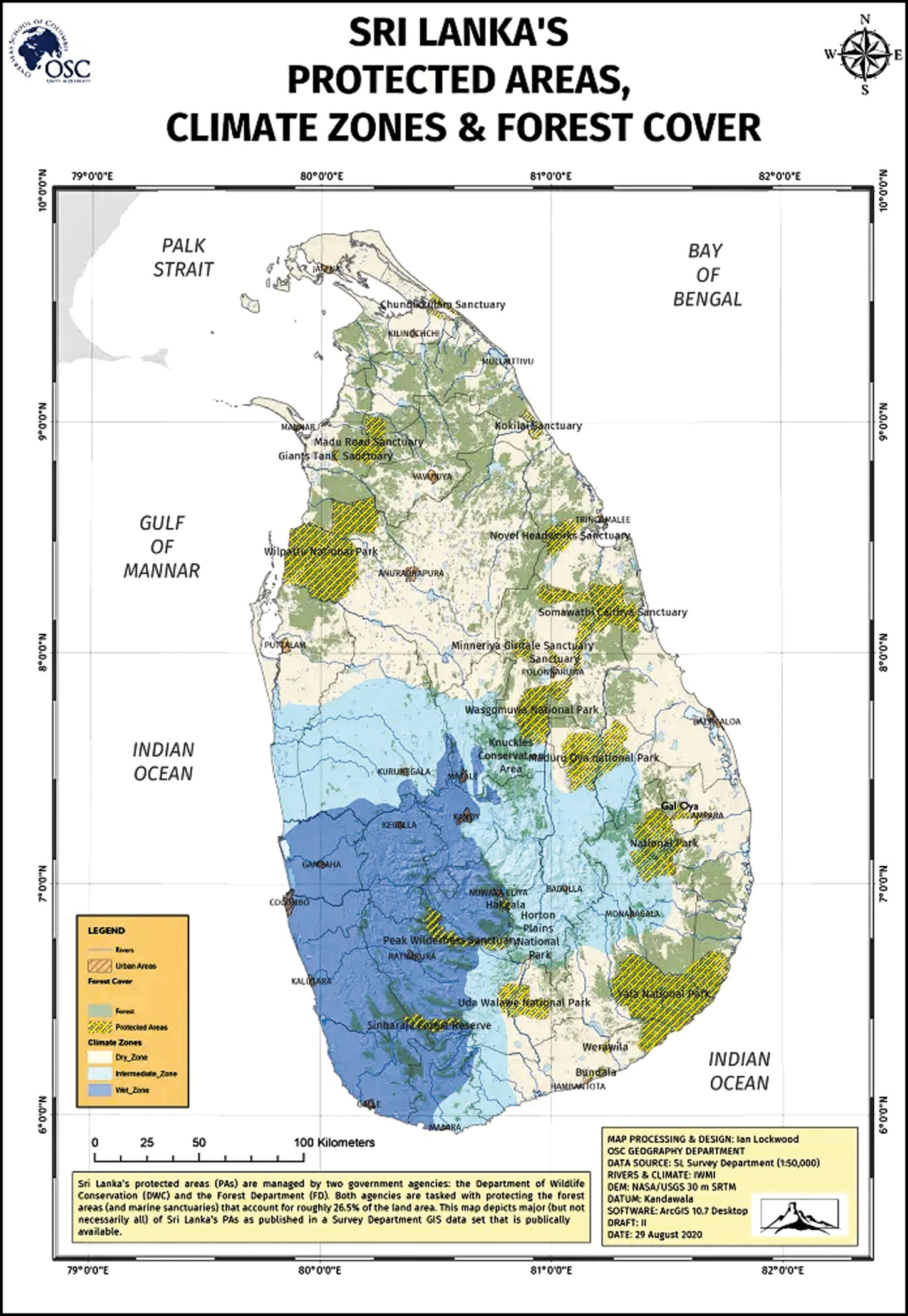

Sri Lanka’s Protected Areas are spread across three major climatic zones (wet, intermediate and dry). There are countless restoration and rewilding efforts in all three zones.

Restoration To The Fore

In response to the challenges there is a broad-based consensus that more needs to be done to protect Sri Lanka’s natural heritage. Increasingly, ecological restoration is an important part of the conversation. Several groups, including NGOs, large hotels and government agencies, are working on restoration projects in a variety of habitats in the diverse climatic zones of the island. The Sri Lankan Government is partaking in the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. These efforts involve a wide variety of different habitats, ecosystems and stakeholders.

Popham’s Arboretum

A pioneering effort to put ecological restoration to work in a time when the concept was not in the public discourse happened at Popham’s Arboretum, in the dry zone forests at the centre of the island. This part of Sri Lanka, with the iconic Sigiriya rock, is more famous for its architecture and cultural significance. Observing freshly-degraded forests, Sam Popham, a retired English naval officer and tea planter, set about restoring a small patch of chena (slash and burn) land that he had purchased on his pension. At a time when fast-growing tree varieties were all the rage of afforestation programmes, he used indigenous species. Over the course of many years, Popham developed what he called ‘assisted natural regeneration’ to bring back the dry zone forest. Although he passed on in 2022, Popham’s Arboretum is thriving and is open to the public to showcase his methods. The forest has regenerated and become a home to a variety of plant and animal species. His methods have had an impact – other individuals and hotels have applied similar approaches (one example is Dr. Ranil Senanayake’s experiment with analog forestry at the Belipola Arboretum). Notably, these dry zone forest restoration sites have seen a return of key species such as fishing cats Prionailurus viverrinus and the grey slender loris Loris lydekkerianus.

Rewilding

Definition: “Rewilding is the process of rebuilding, following major human disturbance, a natural ecosystem by restoring natural processes and the complete or near complete food web at all trophic levels as a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem with biota that would have been present had the disturbance not occurred. This will involve a paradigm shift in the relationship between humans and nature. The ultimate goal of rewilding is the restoration of functioning native ecosystems containing the full range of species at all trophic levels while reducing human control and pressures. Rewilded ecosystems should – where possible – be self-sustaining. That is, they require no or minimal management (i.e., natura naturans [nature doing what nature does]), and it is recognised that ecosystems are dynamic.” (Carter et al.)

Sinharaja’s Surprise

The most important example of ecological restoration in Sri Lanka took place through a curious combination of unplanned and deliberate interventions in the southwest wet zone. Sinharaja rainforest, a celebrated World Heritage Site, was the setting for these events (see Sinharaja - The Heart Of South Asian Biodiversity). Today, the area is known for its lowland rainforest dominated by Mixed-Dipterocarp Forest (MDF), and astounding biodiversity. However, starting in the 1960s and up into the mid-70s the forest was being selectively logged for industrial production of paper and plywood. It was a different age, and the leaders of the time looked to utilise nature and wild resources for immediate human benefit. Large swathes of the forest that now make up the core zone were gutted. The plan was to harvest a ‘sustainable yield’ of timber – which was a nice theoretical concept that environmental managers championed, but had unintended consequences. Skid trails were put in to access forest areas; these ended up devastating much larger areas than intended. Grainy colour prints from the time show how mechanised logging reduced valleys to muddy wastelands. The loggers, led by Canadians, used to operating in temperate conditions, had little appreciation for what they were destroying. The Forest Department originally planned to replace the logged forest with fast-growing, non-native mahogany Khaya senegalensis. The area’s biodiversity was simply not a part of the long-term plan or calculation.

It took a people’s movement and a few far-sighted leaders to stop the logging and notify the main parts of Sinharaja as a protected site. Several students from Sri Lanka’s leading universities were studying aspects of the forest; they would go on to lead long-term studies that would record just what a treasure trove Sinharaja was. The focus was on stopping the logging, and that was achieved. But what of the valleys and hillsides that had been ravaged by the logging?

Over the years, with consistent protection and virtually no human impact, a miracle unfolded in Sinharaja, illustrating the resilience of tropical rainforests when given a chance. Nature, once allowed to do its part, self-regulated and healed its wounds. Processes of ecological succession were vital to Sinharaja’s recovery. In the core area, significant neighbouring ridge forests and other patches of inaccessible forest had survived the ravages of logging. These species fruited and seeds were dispersed by wind, water and the creatures of the forest. Slowly but surely, and then at a rapid pace, the rainforest regenerated itself at all trophic levels. Recovering forests provided a home for the emblematic endemic species and mixed-species bird flocks that visitors now seek.

Experiments in ‘Analog Forestry’

Systems ecologist Dr. Ranil Senanayake has pioneered what he has coined as ‘analog forestry’. This is a method of ecological restoration “that creates ecologically stable and socio-economically productive landscapes. Analog forestry is a complex and holistic form of silviculture, which minimises external inputs, such as agrochemicals and fossil fuels, instead fostering ecological function for resilience and productivity. Analog Forestry values not only ecological sustainability, but recognises local rural communities’ social and economic needs, which can be met through the production of a diversity of useful and marketable goods and services, ranging from food to pharmaceuticals and fuel to fodder” (IAFN). The Belipola Arboretum in the Central Highlands has been the site of the first Sri Lankan experiment in Analog Forestry.

Blocks of Sinharaja were initially mapped as either primary (unlogged) forest and secondary (logged) forest or timber plantations (mainly Pinus caribaea). Today it is virtually impossible to detect signs of the violence that logging had scarred on Sinharaja’s heart. The once-paved logging roads have disappeared and concrete bridges have tumbled into streams. A towering canopy of different species covers areas that were bare. Calamas ovoideus, a species of cane that loves sunlight and grew up with the mid-successional species, has peaked in secondary forest and is now dying out as climax species take over. Late successional trees of the MDF species are on the return.

Beddagana Wetland Park is an urban wetland ecosystem in Colombo that has been restored from a garbage dump and construction site. It hosts a variety of species including resident and migrant birds. The wetlands act as an important flood control mechanism and are popular with residents as a place for walking, wedding shooting and bird photography.

Timber Plantations To Rainforest

Nature provided the catalyst in the core of Sinharaja, but on its edges, a little help from human hands brought about equally exciting changes in restoring degraded habitats. Starting in the 1980s, scientists from Peradeniya University and the Yale School of Forestry, under the Smithsonian Tropical Forest project, initiated a long-term study of one hectare of primary forest in Sinharaja. Their landmark studies helped to document patterns in floral diversity and demonstrate Sinharaja’s richness. Several scientists from these collaborations experimented with restoring Sinharaja’s degraded edges. The findings of these efforts were published this summer in a book titled, Ecological Restoration.

Sinharaja’s boundary had been planted with fast-growing Pinus caribaea to mark its boundary, and perhaps for eventual use as a source of timber. These plantations of Mexican trees were of little ecological or economic use in the Sinharaja context. Starting as early as 1991, a few plots were identified to bring back the rainforest. The key approach was understanding forest dynamics and site-specific plants that would kickstart processes of ecological succession. Quantified experiments were run on the plots clearing single, double and triple lines of Pinus and trying out different early successional species. Collaboration with the Sri Lanka Forest Department was critical. At first, it was challenging to shift them from a monoculture to a mixed-native-species approach. That shift in perceptions – from afforestation to one promoting biodiversity – is a fundamental shift of world views and practical approaches that has been fundamental to global approaches today. Planting medicinal and herbal species that would have local benefits for the human communities on the edges of Sinharaja was an important strategy to garner support.

Colombo’s urban wetlands enjoy protection that have contributed to the city being named the first urban Ramsar city. Efforts are now underway to better protect these habitats. The author’s students are in a kayak clearing out water hyacinth from the Talangma wetlands as part of a restoration effort.

I happened to be an accidental witness to the changes in the edge plantation plots of Sinharaja where Nimal Gunatilleke’s experiments in the Pinus plantation were being conducted. I have been visiting Sinharaja three to four times a year since 2000. I take annual study groups there and also visit on my own to look for birds, reptiles and amphibians. Mostly I seek solace in the forest and the community of people who have opened up their homes to me, my students and friends. Taking the long route up to Martin’s Jungle Lodge (where all good birders stay) you pass through a boundary patch of Pinus. This is where teams have been thinning the forest and planting succession-appropriate species. I was aware of the efforts but not really paying attention to the speed of change. On my last visit in May, I was astounded by just how well the native vegetation had grown. After nearly two decades of growth, the Pinus is dying off to be replaced by strands of Canus and other mid-successional species. On walks with Sinharaja’s guides, we found key endemic wildlife including the Sri Lanka Blue Magpie Urocissa ornata, Sri Lanka green pit viper Trimeresurus trigonocephalus and long-snouted tree frog Taruga longinasus in the restoration plots. Down in the valley near Kudawa, Pinus forests undergoing succession have become the best-known localities for key bird species such as the Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni. Knowing how well the process of ecological succession worked in the core zone, we can expect a healthy recovery of this area. The hope is that the plot demonstrates how Sri Lanka’s rainforests can be restored by following steps that recognise the importance of site-specific ecological succession.

Ecological Succession and Restoration

A key concept in the field of ecology is ecological succession, a process in which degraded ecosystems (or new landscapes) undergo a series of predictable steps as they go from pioneer communities to climax systems. Most ecosystems are dynamic and are always going through natural processes of change. In terrestrial systems, abiotic factors such as soil moisture and sunlight can play a critical role in what species survive and flourish. Productivity increases and then stabilises while mature ecosystems support greater diversity. Professor Nimal Gunatilleke and his colleagues have conducted long-term studies that have shown how important an awareness of natural stages of succession is when conducting restoration efforts. Many restoration (and afforestation) efforts have failed when inappropriate species have been planted. The lesson from several study plots in Sri Lanka is clear: keep in mind the stage of succession at which the landscape is at and what species would normally thrive there before you start. For example, in cleared forest land that has been overgrown with weeds, there is little point in planting climax species that need shade conditions. It is better to start with sun-tolerant, mid-successional species and then phase in the climax species once shade and soil conditions have been established. The more that humans can try to mimic stages of ecological succession the greater success they will find in restoring and rewilding damaged landscapes.

Balancing For The Future

I live on the eastern outskirts of Colombo near the administrative capital of Sri Jayewardenepura. The area is remarkable for its wetlands, which have been protected and safeguarded from ‘development efforts’. These areas help absorb rain bursts and mitigate flooding. I use them as living classrooms and often spend my weekend mornings wandering around these spaces with binoculars. I’m blown away at how they are turning into fine sanctuaries, hosting species that you would normally not expect in an urban setting. Invasive species such as water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes pose a serious challenge to Colombo’s urban wetlands but individuals, government agencies and NGOs are working to remove them and bring back a state of ecological balance. Processes of ecological succession are taking place in the urban wetlands – something that is evident not only in the floristic community but in the animals that thrive in the urban wetlands. Fishing cats Prionailurus viverrinus, Eurasian otters Lutra lutra, and saltwater crocodiles Crocodylus porosus have all found homes in these urban wetlands. Birdlife is impressive and the migration season is delightfully diverse. Like some other rewilding efforts, these were not targeted introductions. However, once the habitat was protected and allowed to thrive, the species have found a home amongst the hustle and bustle of human activities. The challenge for Sri Lanka is to balance these wild neighbours with human needs. Based on the island’s long history of human-wilderness coexistence, there is every reason to be optimistic for the future.

Tourism and Nature in Sri Lanka

The tourism industry in Sri Lanka, a vital part of the economy, emphasises natural experiences. All good tourism promotional media advertise wild encounters with elephants, leopards and/or whales in addition to the gorgeous beaches, rolling tea estates and heritage of the cultural triangle. For the most part, this has been good for wilderness protection and efforts to achieve better environmental stewardship. The role of tourism is such that it makes good economic sense to protect and manage wilderness areas rather than divert them for other uses (mining, forestry, agriculture, etc.). Many communities living next to Protected Areas have a vested interest in tourists visiting these sites.

-1200_1696570346.jpg)