M.K. Prasad (1932 - 2022) Pioneer Of A people’s Movement

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

By Anand Parthasarathy

First hailed for his efforts to save Silent Valley, Prof. Prasad spent the subsequent decades spreading his passion for sane, people-centric environment management.

Shortly after the Indian government formalised the rescue of Silent Valley in Kerala in 1985, by designating it a national park, I was commissioned to do a magazine feature and sought help from Professor M.K. Prasad (or MKP). He was in a rush when I called at his Kochi home – on the way to the Boothathankettu reservoir, 50 km. away in the Western Ghats, where he was leading a protest against proposals to set up a nuclear plant (the plan was subsequently abandoned).

“Don’t become another armchair journalist,” he told me in his characteristic blunt manner, “If you want to write about Silent Valley, get your feet dirty, trek through it first.” Then he scribbled a note of introduction to the then Chief Wildlife Warden of the national park and veteran forester, Mohan Alembath, and gave me a quick lecture on what flora and fauna to look for (and how best to tackle the leeches). I did get my feet dirty (and leech-covered) in the soil of Silent Valley – and it changed me forever.

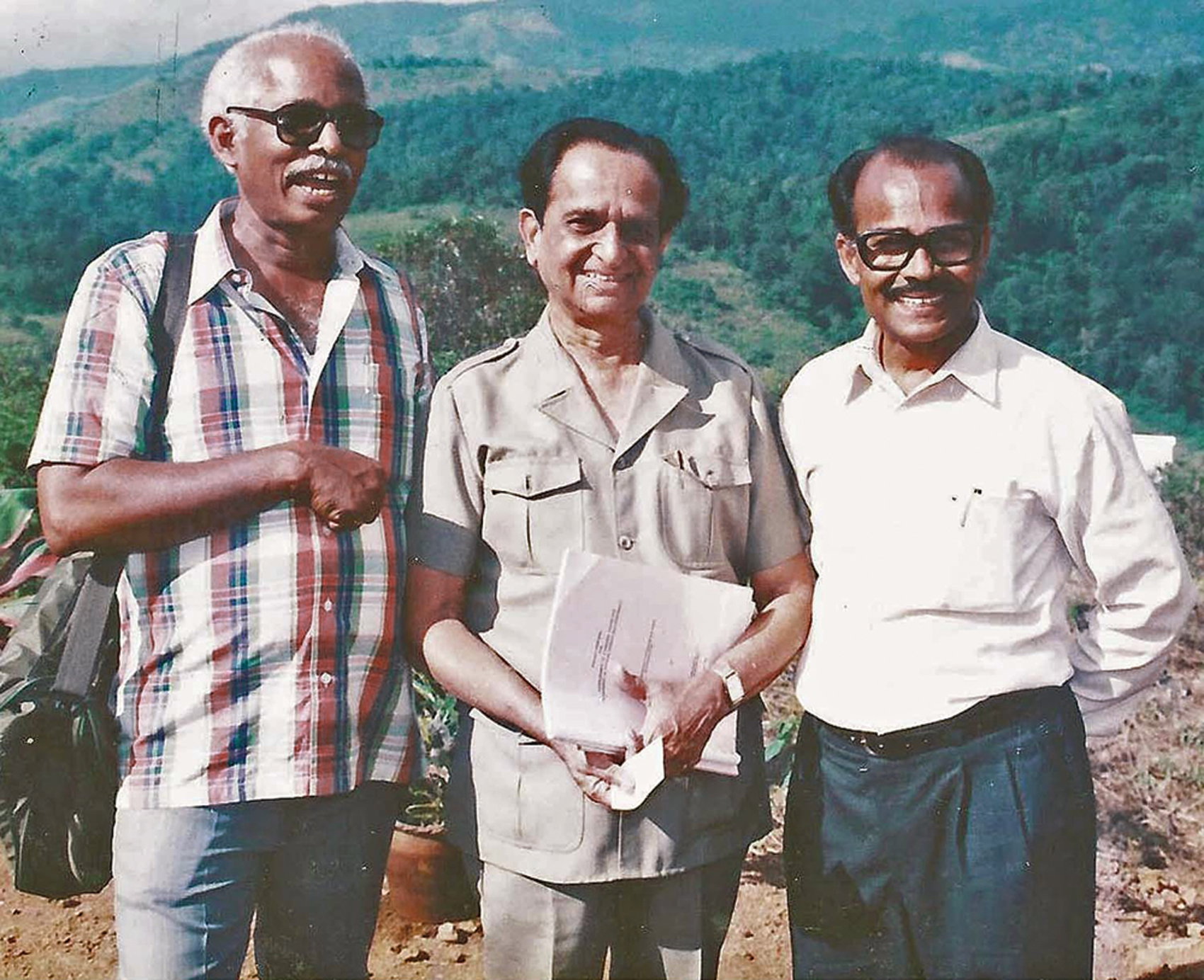

M.K. Prasad’s passion for environmental management with people at the centre, straddled the local and the global. Photo: Shanmugham Studio Kollam (Wiki commons).

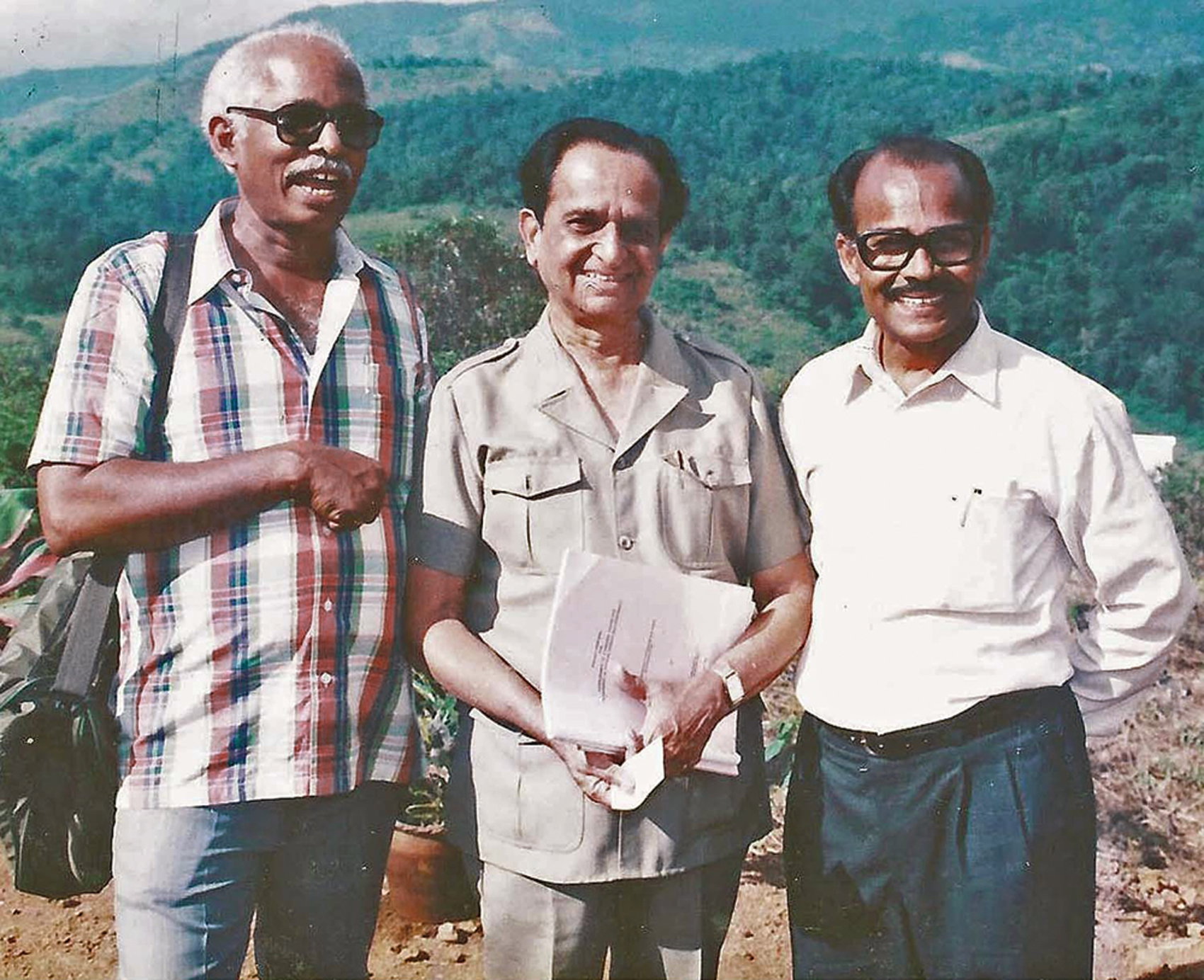

Many participated in the popular movement in the early 1970s that finally helped save the precious tropical rainforest tract from inundation for a hydroelectric project across the Kunthipuzha river. Scientists M. Balakrishnan and V.S. Vijayan of the Kerala Forest Research Institute were the first to document the potential damage that a hydroelectric project would cause. Zafar Futehally and Dilnavaz Variava used the Bombay Natural History Society as another forum. “Snake Man” Romulus Whitaker, raised the alarm after he visited the Valley. Rom says today: “We may have been whistle-blowers, publicising the threat facing Silent Valley in 1973 in the WWF-India Newsletter, but it was Professor M.K. Prasad, heading the Kerala Sasthra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), who spread the word, bringing many luminaries on board like Sálim Ali, Sugathakumari, Mrinalini Sarabhai and M.S. Swaminathan. This is how he gained massive national and international support.” And crucial help came from the then head of WWF- India, M.A. Parthasarathy who figured out creative ways to finance some of Prasad’s campaigns and road shows.

‘Act locally, think globally’ is a mantra of the green movement. M.K.Prasad’s passion for environmental management with people at the centre, straddled the local and the global. An observer at the first UN-sponsored Earth Summit in Rio, he used the opportunity to visit the Brazilian rainforest and learn how it could be conserved and provide livelihood to indigenous people, even while harnessing its attractions to motivate visitors from the cities. And he used his learnings to help KSSP set up a unique Integrated Rural Technology Complex (IRTC) near Palakkad, which pioneered solutions in solar power, biogas and solid waste management, long before the government embraced them.

Prof. M.K. Prasad receiving an award on behalf of Kerala Sasthra Sahitya Parishad from the late Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on November 19, 1986. Photo: M.K. Prasad personal collecion.

Requiem For A Tree

No issue concerning nature was too small for MKP. One morning in December 1994, I received an uncharacteristically agitated call from him. A large roadside rain tree, close to his home in Ernakulam, providing shade for decades to weary passers-by, had disappeared. MKP had fought alongside local residents to protect the tree, but ‘developers’ finally did the deed at the dead of night. “I propose to lay a wreath on the tree stump. I don’t think anyone cares, but I must do it,” he told me. In those days I used to write a people-friendly column, ‘Between You and Me’, in The Hindu. I urged MKP to delay his funeral rites for the tree, until I reached with my camera. With only a few passersby as audience, he laid his wreath with a card in Malayalam, which said simply: Vriksha Snehi, tree lover. I snapped the moment and featured it in my next column. MKP’s action drew a huge reader response, as did his revelation that when the owner of the flower shop, which supplied the wreath heard about the purpose, he refused to take payment. For Prasad, even defeat was often a victory of sorts.

Over seven decades, there is hardly a year when MKP was not leading a campaign: livelihood of farmers in the Kuttanad heartland, where saline water destroyed crops; pollution by rayon factories along the Chalayar river near Kozhikode; attempts (stalled, but still active today) to build a dam for electricity at the beautiful Athirappilly waterfalls of the Chalakudi river, conservation of mangroves along the western coast, relief for victims of the Bhopal gas tragedy and evacuees of the Narmada Valley schemes…

“Don’t become another armchair journalist,” Prof. M.K. Prasad told the author in 1985, adding “If you want to write about Silent Valley, get your feet dirty, trek through it first.” Photo: Public domain/Wikipedia.

M.K. Prasad: A Man For All Seasons

Professor Manaparambil Koru Prasad was arguably India’s best-known evangelist for sane environmental management, which embraces all sections of society but remains particularly sensitive to the concerns of the voiceless.

Born in 1932, in Cherai, a village on Vypeen island off the Kochi coast of Kerala, the son of M.K. Koru Vaidyar, a practitioner of indigenous medicine, Prasad chose Botany as the optional subject in class nine – and later obtained his B.Sc. in Botany from Maharaja’s College, Ernakulam and an M.Sc. in the same subject from the Birla College of Science, Pilani, in 1955. Recognising his brilliance in Botany, his professors urged him to continue studying for a doctorate – but the family’s financial situation forced Prasad to seek employment – as a demonstrator in a government college in Chittur, Palakkad district. He was to serve the Kerala government college system for the next three decades, as Botany lecturer and professor, Principal (of Maharaja’s College) and Pro Vice Chancellor (Calicut University).

Exposed for the first time to modern concepts of ecology and conservation in a month-long Indo-British summer school in 1964 and inspired by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which had been published two years earlier, Prasad took an active part in the work of the newly-founded Kerala Sasthra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), roughly translated as the Kerala Peoples’ Science Movement. In 1971, Prasad’s school-day friend U.K. Gopalan, a marine biologist, founded the Cochin Science Association and the duo used the forum to evangelise science and environment, with a people focus. The Silent Valley controversy was the first big environmental issue that they embraced – and for Prasad, it was the first step in a lifelong mission to critically examine every development project through the lens of environment and people.

He became the voice representing people rather than governments, at forums like the World-Wide Fund for Nature (then WWF), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the UN Environment Programme and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Board. At home, his down-to-earth, unvarnished views were welcomed by bodies like the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, the Centre for Science and Environment, the Centre for Environment Education, the Bombay Natural History Society, the All-India Peoples Science Network and the Kerala State Biodiversity Board.

Unusually, the Kerala government appointed him Executive Director of the Information Kerala Mission, a largely tech-driven body charged with computerising local government institutions. It was an inspired choice: Prasad’s humanism helped tweak their technology solutions.

Until COVID-19 snatched him away on January 17, 2022, only months from his 90th birthday, M.K. Prasad continued to harness his experience and his wide acceptance across political divides to evangelise initiatives and programmes that put ordinary citizens at the epicentre of planning. One of his last acts was to sign an open letter by leading thought leaders, opposing a plan to build a new high-speed railway line along the length of Kerala, before a full study of the environmental consequences was done.

Prof. Prasad is survived by his wife and support for 60 years, Shirley, a distinguished academic in her own right and an active social worker. Their children Amal Prasad and Anjana Sunil are married and settled in India.

Renaissance Man

But this Renaissance Man of Nature had yet more to contribute. After his formal retirement from service, the Kerala government appointed him Executive Director of the Information Kerala Mission (IKM). I was then a member of the jury for the state’s e-governance awards and had to evaluate the projects at IKM. “I won’t send you a brief, come and see for yourself,” he said, taking me to the Trivandrum General Hospital. There, he pointed me to a kiosk, where a mother who had given birth to her child just days ago, received the birth certificate, even before she went home. He brought humanism and a common touch that still characterises so many of Kerala’s citizen services.

Prof. M.K. Prasad inside the Silent Valley National Park with environmentalist Dr. U.K. Gopalan (right) and former WWF-India head, the late M.A. Parthasarathy for the 10th anniversary of the park in 1995. Photo: Anand Parthasarathy.

A week later, at his insistence, I attended a meeting in the Kerala hill resort of Munnar, bordering Tamil Nadu, where Prasad introduced a new IKM-crafted local government planning software, Sulekha, to members of nearby panchayats. “I need your help. They conduct most of the business in Tamil,” he told me. I went along, as interpreter – and ended up with new learnings, as he used the opportunity to inspect how rampant construction of resorts on hill slopes was depleting the groundwater and triggering landslides. It was the sort of experience that made everyone who encountered M.K. Prasad the next recruit to serve man and nature in a newer, humbler and more meaningful way.

Anand Parthasarathy is a technology journalist trained in environmental reporting, who wrote about Prof. Prasad’s many initiatives for three decades – and ended up as a team member of some MKP-led projects. He is based in Bengaluru and is editor of the tech portal www.indiatechonline.com