Letter To A Friend

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 10,

October 2025

By Bittu Sahgal

Dear Valu,

Memories are mixed blessings. On the upside, the best times spent with you at home and in the forest come to mind, as do the many battles we fought and won. Even those we lost taught us how to fight and win other battles. The downside? Memories drum up pain… the kind coursing through me as I write, knowing that you’ve gone. That hurts, Valu. The sadness I thought I had dealt with comes flooding back.

The urge to speak with you crops up frequently. India never needed you more than it does today, because too many officials, judges, businessmen, legal eagles and scientists that we had painstakingly won over to the side of wild nature have gone. And a scary number of their replacements have proven to be pliable shortcut takers and Trojan Horses.

As I write, the thought occurs… why this monologue? By its very nature it’s little more than an emotional and intellectual cul-de-sac. The point-counterpoint that defined our relationship over four decades renders this effort to speak with you, in the echo chamber of my own head, insipid. In many ways, we were chalk and cheese. I was mild. You were gruff. I was full of doubt on the way forward, wanting to win public opinion to keep the tiger alive. You said you knew what had to be done and were vociferous about it: “Keep people out of its forests and the tiger will thrive.” The man who bound us together was Fateh. Sitting around a crackling fire under Jogi Mahal’s banyan in the dead of winter, we spoke little. Silences were sacred. His advice prevailed. Both strategies were deployed. The tiger is still alive.

Valmik Thapar, his wife Sanjna Kapoor and their son Hamir in happier times. Photo Courtesy: Sanjana Kapoor.

Neither of us have ever been real political animals, Valu. Yet, we have both had to deal with dark politics virtually every day of our lives. As always, you articulated your views more directly than me. Here is what you wrote in Tigers My Life (Oxford 2011):

Unlike my parents I was not very political but my engagement with the government over the last 20 years has made me furious about the state of the nation and if this general state does not change then the tiger will never be saved… well intentioned people can’t make the difference they want to because money has eaten into the souls of many people, most of them in power.

I remember how in the winter of 1999, when the Y2K scare had India and the world in a twist, I mentioned Y2K in passing around the Jogi Mahal campfire, and Fateh said in Fateh style टायगर काे (expletive) काेई फरक नही पड़ेगा (It won’t make a damn difference to the tiger!). That was our sole focus then… the tiger and the fear that it may not survive. Three years earlier, when we were losing a tiger a day to poachers, and retaliatory killings turned rampant thanks to the abysmal leadership of the then Director of Project Tiger, you and I had jointly warned India that we had but 1,000 days to save the tiger. It was a pivotal moment in both our lives. After weeks of discussion and days of argumentative editing, here are snippets of what we communicated together to the public in Sanctuary Asia’s Vol. 16, No. 9, September 1996 issue:

As we go to press, constituents of Tiger Link, a forum launched in February 1995 in defence of the tiger, have decided to escalate their battle by taking it to the people. This may well prove to be the last hope for the species because the voices of many tribal groups and leaders such as Medha Patkar of the Narmada Bachao Andolan, and Dr. B. D. Sharma, ex-Commissioner Schedule Castes and Schedule Tribes, have been joined to those of socially conscious wildlifers in defence of natural India and the tiger itself. To succeed, however, these groups will have to climb the wall built by powerful but visionless men guided by the light emanating from the World Bank. The outcome of this battle will be determined by the ability of very diverse groups to get together in joint purpose. Saving the tiger amounts to saving forest cultures, which are in retreat even faster than the tiger itself.

In any event, in the name of sanity, we charge the people of India with the responsibility of saving the tiger before the turn of the century. We have but 1,000 days in which to accomplish

our task.

And Valu, we had our moments away from Ranthambhore too. Madhu, you and I visited Madhya Pradesh’s Churna Sanctuary that we so desperately wanted to have declared as a tiger reserve. Here too, our different personalities saw us pore over draft after draft until we got it across the post. While you and I were poking a fresh tiger dropping, condensation still rising, Madhu, walking with a forest guard some metres ahead, stage-whispered, “Tiger, Tiger”. Neither of us got to see the cat that ghost-like vanished into its emerald forest. Later both of us sat glumly over a cup of tea, for neither of us at that point had seen a tiger on foot, despite many long walks in tiger country, when with Fateh we were ‘building’ Ranthambhore. Back at the Churna Forest Rest House Madhu not-so-subtly rubbed it in: “Who told you guys to look into every piece of shit you come across? You should walk to experience the forest instead!”

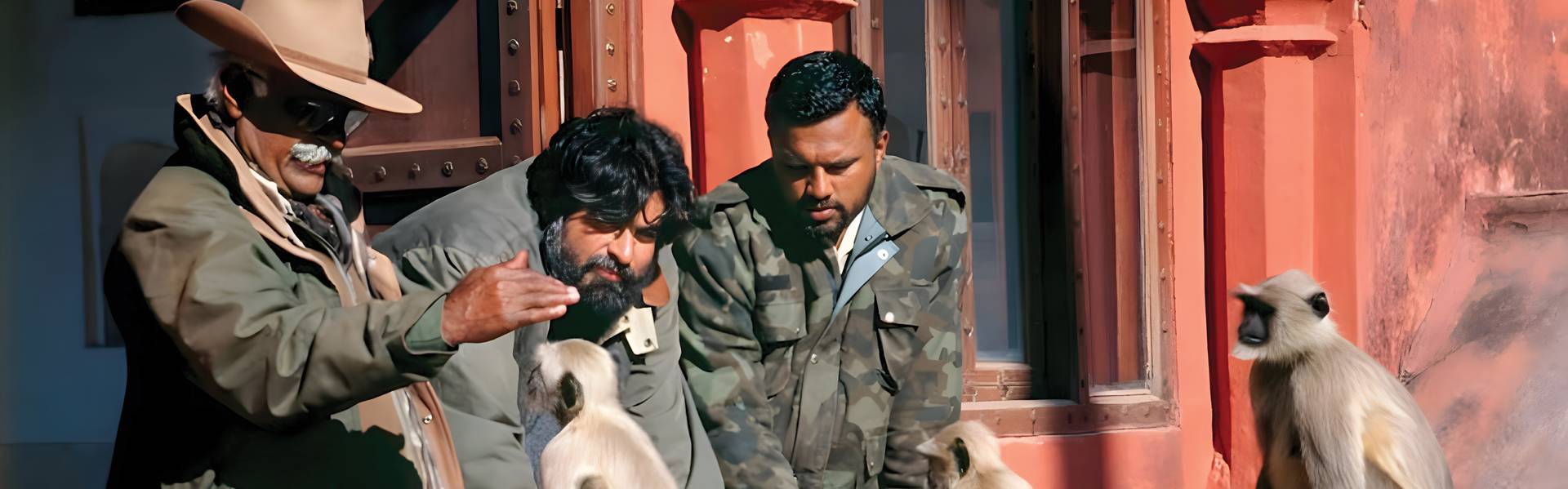

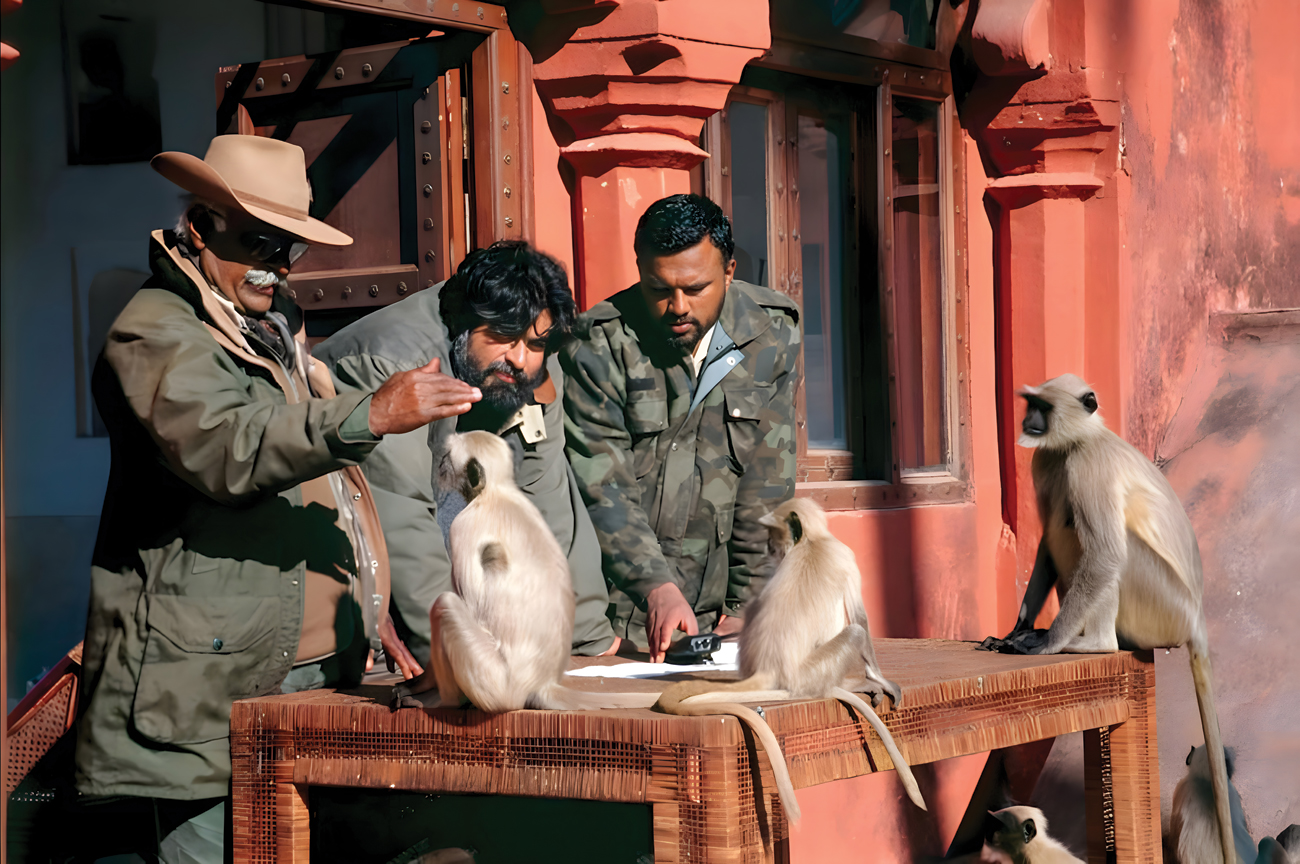

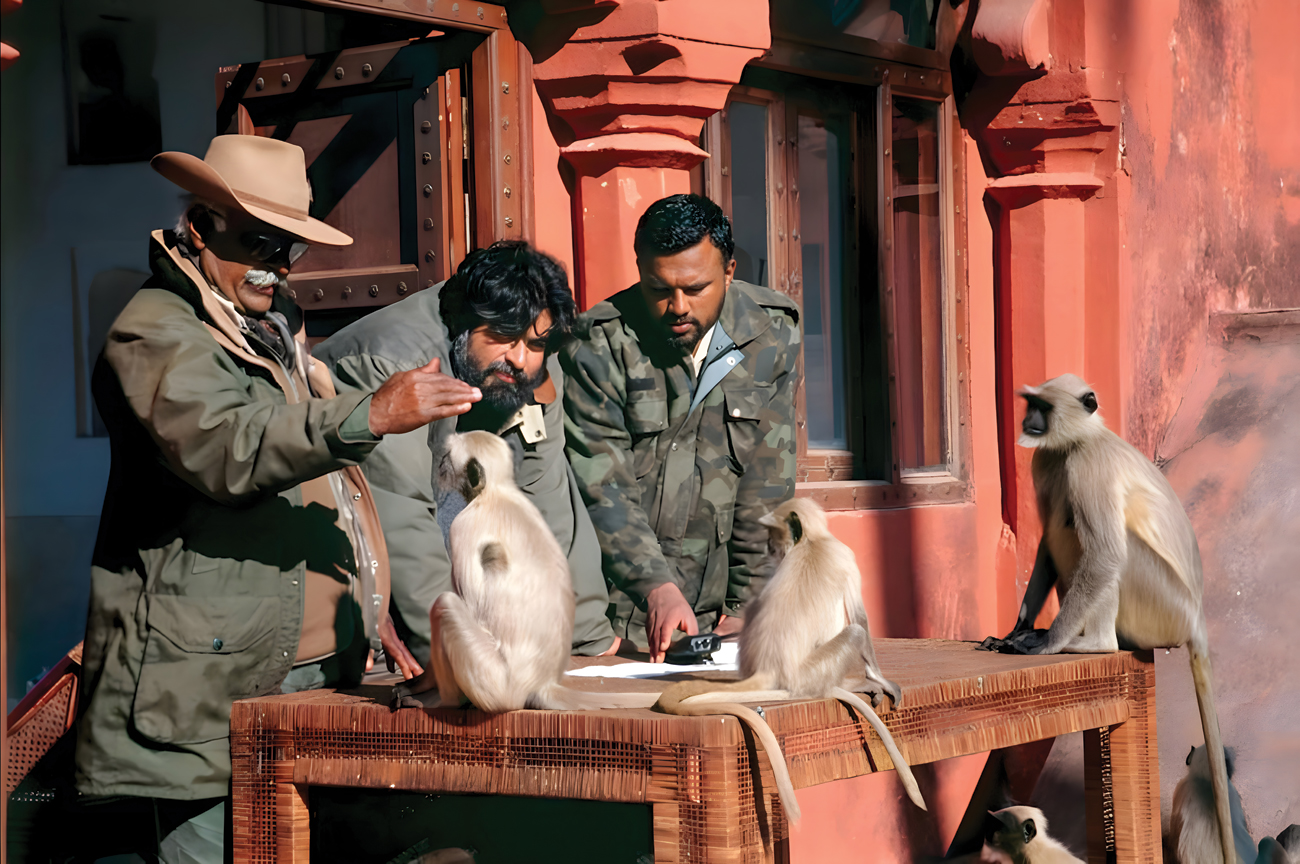

Fateh Singh Rathore, Valmik Thapar and G.V. Reddy, at one time the ‘Three Musketeers’ who worked in unison to defend Ranthambhore, discussing strategy, overseen by three primates that had the run of this amazing forest, long before the advent of Homo sapiens. Photo: Sanctuary Photolibrary.

Here is what both of us penned back in 1996, post that Bori-Churna trip:

We followed her pugmarks on foot for over a kilometre through dusty paths and damp rivulets. The trail suggested that her two cubs, despite a myriad distractions, never drifted more than a few metres from the protective reach of their mother. By the side of the road, obscured from view, we saw fresh droppings where the feline had stopped to defecate, scratching the earth to leave a momentary, “I was here” message in the distinctive manner of tigers. Did the stiff brown bristles belong to a now-departed sambar? Or a wild boar perhaps? Only laboratory analysis would provide a conclusive answer, but for the moment we were pleased enough to know that despite all our failures the tiger had managed to survive in yet another forest.

We were in the Churna Sanctuary, in December 1995, walking through a little-known, inaccessible section of Madhya Pradesh’s fast-vanishing tigerland. We had driven from Pachmarhi and Bori, through deep ravines and gorges which easily rivalled some of the world’s most celebrated natural monuments. Less than an hour ago, we had stopped at an impressive rock shelter, where we gazed in wonderment at works of art left for posterity by a community of forest-dwellers more than 10,000 years ago. Like an awning, a massive rock overhang protected tigers, elephants, deer, snakes and langurs, all etched indelibly on an ancient 30-metre-long stone canvas. A melancholic thought haunted us as we pondered the fact that future Indians would probably be able to view this gallery 20 years from now... but not its star subject, the tiger.

Despite an endless stream of rhetoric and lip service, the tiger continues to die. Masters of paper policy, we cannot implement anything on the ground. The time-lag between intent and action must pass through a bureaucratic minefield where tiger games are continuously played by those who damage the animal they are employed to protect.

Photo Courtesy: Sanjana Kapoor.

No marks for guessing which of us penned the above para, which came accompanied by as polite an instruction as you have ever sent me: NO EDITS! And here is the more you YOU!

One might have hoped that well-funded environmental organisations would have stepped into the breach, but they too carried unwieldy bureaucracies of their own, virtually supported by government grants and largesse. More often than not, therefore, the larger NGOs chose to look the other way when they were asked to criticise government, or ministers, openly. Large donations, nevertheless, poured into such agencies from the international community over the years in the name of the tiger. No amount of wriggling now can obliterate the fact that these badly needed funds remained unutilised for years as poachers ran riot through Tigerland. Meanwhile, the gigantic green enterprises wrapped themselves up in self-woven webs of rhetoric and pettifoggery. Instead of heeding the advice of those who routinely dirtied their feet in the field, such organisations placed a premium on individuals with the ability to produce a good turn of phrase and, of course, money and still more money.

Too many people made snap judgements about you because you refused to play the softness-politeness game. But I’ve seen the soft side of you. The vulnerable side of you, which lived in the shadow of the strategic you and your colleagues on the Supreme Court’s Central Empowered Committee, notified on May 9, 2002. You guys gifted the tiger and its home at least two decades of life.

Photo Courtesy: Sanjana Kapoor.

I miss you.

You and Sanjna opened your heart and your home to me. To the day you left, we were brothers in arms. I’ve seen Hamir grow before my very eyes from a tiny racing car aficionado, into a fine young man with a passion for the wild. In my mind’s eye I can still see you, my monosyllabic friend, hunched over your computer in the basement of your welcoming home which, for all practical purposes, is as fine a tiger museum as anyone could ask for!

Rest well, Valu. See you on the other side.