Intertidal Wonderlands

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 10,

October 2025

By Deepika Sharma

Agatti Island, Lakshadweep, March 2024: It felt like I was walking on smooth heaps of talcum powder while on a beach. The sky was awash in pinkish-blue hues from the early morning sun, the water was crystal turquoise, and sandpipers were busily searching for food, creating a scene straight out of a landscape painting. Then, I unexpectedly encountered a sea cucumber and a cushion starfish stranded on the beach, likely left behind by retreating tide shifts. While sea cucumbers and cushion starfish are common sights underwater while snorkelling or diving, finding them washed ashore made me start scanning the beaches more closely for marine life near the beaches in Agatti.

As the tide retreated from the powder soft beaches of Agatti Island, the hidden wonders of its intertidal world began to reveal themselves.

Starfish nestled in tidepools, coral crabs playing peek-a-boo, and sea cucumbers quietly cleaning the seafloor – each step along the shore is akin to entering a secret marine theatre. I discovered that Agatti’s intertidal zone, more than a mere passing curiosity – is a living, breathing ecosystem teeming with life, beauty, and resilience. This is the story of what lies between the tides, and how we can tread more gently in their realm.

Acropora corals exposed in the intertidal zone during a spring low tide at Agatti, a tiny island in the Lakshadweep archipelago in the Arabian Sea. Photo: Abhishek Jamalabad.

Where To Look

As a part of The Habitats Trust’s ongoing project on marine biodiversity monitoring, in collaboration with REEF (Research and Environmental Education Foundation), an NGO run by local marine biologists, I was in Lakshadweep for the very first time.

Before my field visit, I looked up Agatti Island, using Google Map’s satellite imagery, which revealed a tiny island nestled in the Arabian Sea, surrounded by striking turquoise waters that included a shallow rocky lagoon on the eastern side, separating the island from the sea. Far from symmetrical, the lagoon and island were crafted over time by ocean currents and waves. This makes it easier to observe marine life, particularly during low tide when swathes of the lagoon’s floor reveal its diversity of marine life. These intertidal areas are the dynamic zones, alternately submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide. Despite the periodic drying, temperature shifts, and the push-and-pull of waves, intertidal areas support a rich diversity of marine life.

Boulder, Coral Or Rock?

As the water level lowers during low tide, large boulders of corals become exposed along the eastern side of Agatti island. From a distance, these appear like ordinary rocks. However, up close, they can be distinguished from rocks by their intricate skeletal structures called corallites that are unique to each coral species. Corallites contain polyps with stinging cells that help capture prey, but can inflict painful cuts or scrapes as I eventually discovered firsthand.

These corals protect low-lying islands like Agatti, which rise barely two or three metres above the waterline, from the erosion impact of strong waves. Their robust structures dissipate waves, enabling coral reefs to serve as crucial natural barriers to buffer the islands from the force of the open ocean.

Intertidal areas present constant exposure to dry conditions during low tide, and many corals have consequently adapted by growing sideways as a survival strategy. That said, the resilience of corals renders them increasingly vulnerable to sea surface temperatures at the hands of the climate crisis. In 2024, we observed mass-scale coral bleaching. They turn pale white when they lose zooxanthellae – a vital alga that provides them with food and oxygen, and gives them their vibrant colours.

Peek-a-Boo

I once saw my colleague, Abhishek Jamalabad, standing still as a statue, his camera focused on a branching coral Pocillopora sp. Ten minutes later he caught my eye and asked me to peer down at the coral. There, nestled among the branches, was a black-fingered coral clinger Cymo melanodactylus, a small crab no larger than my thumb. Finding crabs amongst branching coral has since become my passion. The clinger crab helps slow the progression of white syndrome lesions on corals, significant because white syndrome is fatal to corals. Other crabs such as Trapezia sp. protect corals by removing harmful sediments and protecting them from predators. In return, crabs get to feed on the coral’s lipid-rich mucus. Very little is, however, known about these tiny denizens and their association with corals.

At the beach one afternoon, we were surprised to spot several peppered moray eels Gymnothorax pictus. Eels, with their serpent-like bodies, might not look like typical fish, but they are. Peppered moray eels usually emerge at night to hunt for small fish, crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp and squids. They are generally reclusive and more shy than other morays, and are not considered aggressive towards humans. Locals believe their sudden daytime appearance is because food scraps are dumped along the shore.

Watching fish at low tide fascinates me, even when the water is only ankle-deep. I once noticed soldierfish Myripristis sp. clustered within a single colony of branching coral, yet managing to move deftly within their confined space.

Not all fish are harmless to humans. The lionfish and scorpionfish, for instance, are venomous, and their sting can potentially result in intense chest and abdominal pain, nausea, hypotension and, in extreme cases, disrupt the heart’s rhythm. The scorpionfish's cryptic colouration and texture makes it difficult to spot on rocky seabeds, while the lionfish, with its striking colours, is comparatively easier to spot.

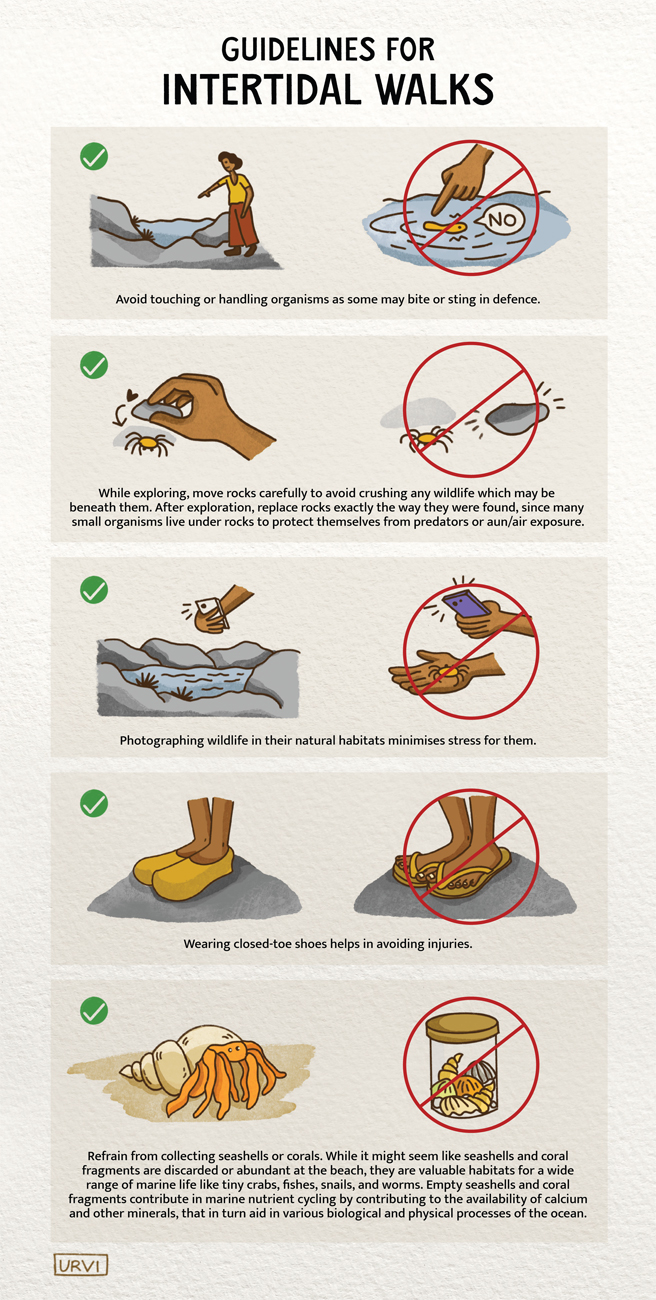

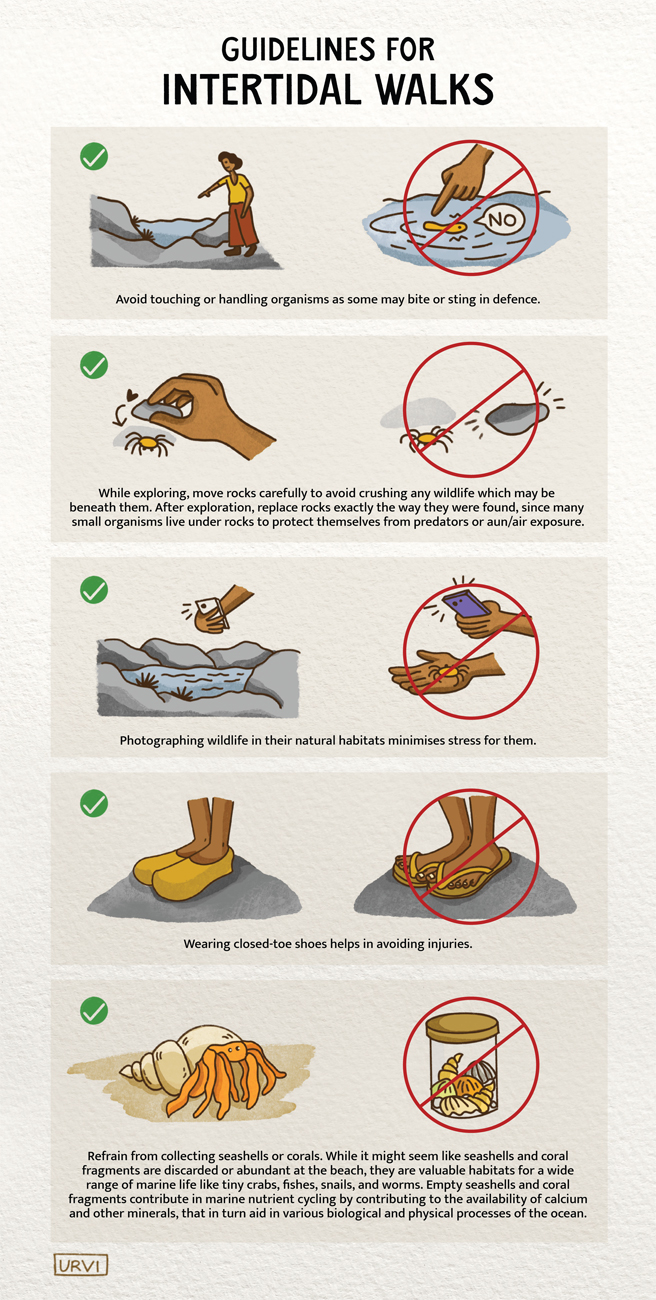

Photo: Urvi Shah.

Intertidal Stars

The cushion sea star Culcita sp. was among the first creatures I encountered in Agatti’s intertidal wonderland. True to its name, it resembles a star-shaped cushion! With its rounded structure, it may not even seem like a starfish at first glance. Cushion sea stars feed on smaller coral colonies, or fragments that their oral surfaces can reach, causing disruption to coral recruitment. Currently, not much is known about them, or even their status in Lakshadweep.

Once while exploring among the rocks, I observed long arms extending from under one. Initially, I mistook it for an octopus, but it turned out to be a lagoon brittle star Ophiocoma scolopendrina. I watched, fascinated as it used one mucous-covered, spiny arm to trap food particles and its other arms to anchor on to a solid structure.

Vacuum Cleaners Of The Sea

Sea cucumbers are hard to miss. Their oblong bodies resemble vegetable cucumbers, but they share close kinship with sea stars and brittle stars. Often called the vacuum cleaners of the sea, they ingest sediment, digest the organic material from sand, and excrete clean sand, effectively recycling nutrients and maintaining the health of the seafloor. While observing sea cucumbers, Abhishek once pointed out a tiny worm Gastrolepidia clavigera, which feeds on sea cucumber tissue. Incredibly, there are over 200 animal species that have been documented sheltering and feeding in or on sea cucumbers.

In Southeast Asian countries, sea cucumbers are a culinary delicacy often targeted by the illegal wildlife trade. Consequently, in 2001, they were listed under Schedule I of the India’s Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, giving them the highest level of legal protection and banning their harvest and trade. Later, in 2020, the Lakshadweep administration declared a dedicated sea cucumber Protected Area – Dr. K.K. Mohammed Koya Sea Cucumber Conservation Reserve – to further safeguard this species.

Photo: Urvi Shah.

Intertidal Plants

Slipping on algae-covered rocks is one of my biggest fears during intertidal walks. Their thin, slimy coating turns rocks slippery and hazardous. In these zones, algae produce mucilaginous compounds that help them retain moisture to protect their cells from desiccation during low tide. Algae are usually easy to spot with their greenish-brown colour and we cautiously avoid stepping on them.

Halimeda sp., another prominent macro alga in the intertidal areas, sport hard calcium carbonate structures that remain even after the plant is dead. Some use its dried form to enhance growth of potted plants.

Seagrasses, islanders inform us, grew lush and dense until 2010, but are now a mere shadow of the past. No one quite knows why the meadows have declined, though some studies suggest that the overgrazing of sea turtles, whose populations have increased concurrent with the decline of their natural predators, sharks. Scientists believe seagrasses are dwindling at the hands of the climate crisis that has caused a rise in ocean temperatures and impacted the very chemistry of the water.

A Fleeting World

The intertidal world is revealed only for a few hours each day – yet within that window lies much to be observed and explored. As rising tides return to reclaim the shore, they remind us that the wonder we witness is fragile, and our responsibility to protect it is real and urgent. These vibrant frontline ecosystems need our attention. By treading gently, staying curious, and sharing what we see, we can help protect the intertidal realm before it vanishes beneath the waves – unseen, and too often, forgotten.

Deepika Sharma works with The Habitats Trust’s Marine Programme, focusing on the conservation of threatened marine habitats and ecosystems. With a strong interest in the intersection of science, community engagement, and policy, her work primarily focuses on the conservation of coral reefs.