Counting Tigers

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 4,

April 2015

By Y. V. Jhala and Q. Qureshi

Wildlife Institute of India

Two stark examples of the co-beneficiaries of Project Tiger come to mind. The central Indian hardground barasingha in Kanha, which was once dangerously close to extinction, and the hispid hare in Kaziranga. More examples will emerge where good management practices are followed. ‑ P. K. Sen, Ex-Director, Project Tiger

Why count tigers?

Tigers are top predators, at the apex of the food chain, so they signify the well being of entire ecosystems, they act as an umbrella species for the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem functions. By monitoring the well being of tiger populations we can gauge the pulse of life-sustaining forest systems.

How can one count wild tigers?

Sanctuary Asia readers might be familiar with the Akbar-Birbal story of counting crows. When asked to calculate the population of crows in a town, the answer given by the witty Birbal could not be disputed since there was no exact way of counting crows. He explained that if crows were in excess then they were visitors from neighbouring villages and if the number was less, then the crows were away visiting their relatives.

The tiger numbers prior to 2005 were an outcome of the bad use of a good field method. Yes, it was the pugmark method – wherein each tiger was believed to have a unique footprint in a good soil substrate. This is true to an extent. An expert tracker would probably be able to identify an individual tiger from a pugmark in a population with which he has been familiar for several years. In the earlier years of shikar and initial years of Project Tiger, the old generation of shikaris who subsequently turned into forest rangers had the tradition of regularly tracking tigers in their beats and mapping their movements. This tradition slowly but surely died over time and the ‘tiger census’ took its place, wherein tracings and plaster casts of tiger pugmarks were obtained – many of poor quality, once in five years. High ranking officials from the city headquarters who were mostly dissociated from field realities then classified these, often rooms-full of plaster casts/tracings to individual tigers. Even God almighty would have a tough time in doing that job, but in their wisdom they declared that tiger numbers kept steadily increasing from an estimated 1,800 in early 1972 to over 3,500 in the year 2000.

Why did Project Tiger get the numbers wrong a decade ago?

This paper castle of tigers began to crumble with local extinctions that could no longer be swept under the grass. The turning point was the Sariska debacle (2004) closely followed by Panna (2007). These small and isolated populations were extremely vulnerable to high-intensity poaching driven by an insatiable illegal market for tiger parts in wealthy China and Southeast Asia. Alerted by this crisis, Dr. Manmohan Singh, former Prime Minister of India, set up a Tiger Task Force headed by environmentalist, Dr. Sunita Narain, to redress the tiger crisis in the country. Then, in 2001, Dr. Rajesh Gopal, took over the reins of Project Tiger and, working with the Tiger Task Force, realised that India did not have a fool-proof assessment of the status of tigers. At that time we did not even possess an accurate country-level map to show where our tiger populations existed, just the belief that India had 3,500 tigers! Dr. Gopal approached us at the Wildlife Institute of India to assist in developing a country-wide methodology to assess the status of tigers in 2002. Animal abundance assessment methodologies were by then quite well developed in the U.S., and Dr. Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society had already successfully applied the camera trap-based method to tigers in the late 1990s. There was no doubt; this approach, based on sound statistical theory, could be applied to individual tiger populations. But the task before us was not that simple. India has about 3,00,000 sq. km. of potential habitat spread across 17 states.

As can be imagined, installing camera traps within 500-800 sq. km. Protected Areas is by itself a humongous and resource-intensive task. We therefore had to come up with smarter, scientifically credible, replicable and economically justifiable approaches to the task of assessing India’s tigers. The difference in what Dr. Karanth had demonstrated in the confines of Protected Areas and what was required from us, was a matter of scale, several magnitudes larger. Our years of experience on working with species ranging across vast landscapes, came to our rescue. Ecological understanding dictates that factors that determine animal abundance are food, habitat, and human disturbance. Data collected includes the number of tiger signs (pugmark and faecal matter) observed per unit effort, the number of prey animals seen per kilometre of transect walked, signs of human disturbance, wild prey dung and cattle dung in a chosen plot, or the number of photographs obtained from remote cameras over a specified duration. Intuitively, as the causative factors become more conducive, animal abundance should increase.

Making intelligent choices

Imagine driving through a Protected Area such as Kanha and a reserve forest such as Balaghat in Madhya Pradesh. In the course of a morning’s drive or walk in Kanha we would typically see several chital, a few sambar, and some gaur. While for the same duration drive or walk through Balaghat, we would consider ourselves lucky to sight a group of chital and a couple of barking deer! From this experience we can undoubtedly infer that there are likely to be more ungulates in Kanha than in Balaghat. To take this further, researchers would, with the help of a compass and laser range finders, estimate the actual density of ungulates by accounting for the possibility of not seeing some animals though they may be present (detection probability). They would then seek to establish a relationship between the density of chital in Kanha and Balaghat and a few other areas, perhaps six or more.

We would also take into account sightings during other morning drives in the same areas. In statistical jargon, we refer to this as double sampling – the first sample comprising a simple economic count (in our case, the number of ungulates spotted on morning drives), while the second sample in the same area is obtained by rigorous scientific methods that are often more resource intensive. This logic was used by us for estimating tiger abundance in large landscapes where it would be impractical to deploy camera traps everywhere that tigers occur. Major tiger populations are assessed by camera traps, while simultaneously collecting information on easily and economically available factors such as habitat extent and quality, prey abundance, human pressure and tiger sign intensity.

This relationship was subsequently used to estimate tiger abundance from areas that were not camera trapped but did have confirmed tiger presence.

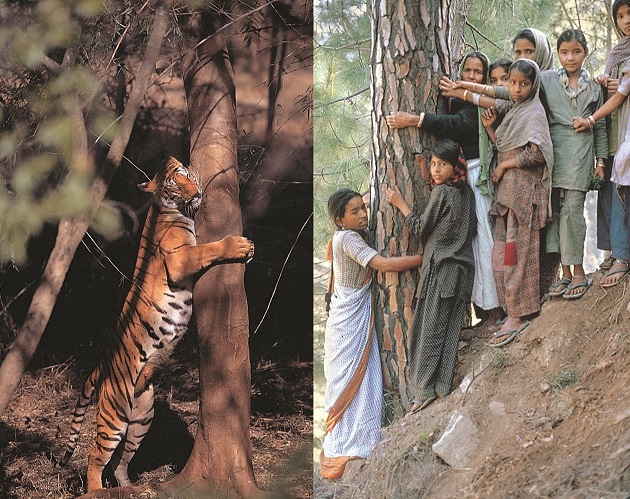

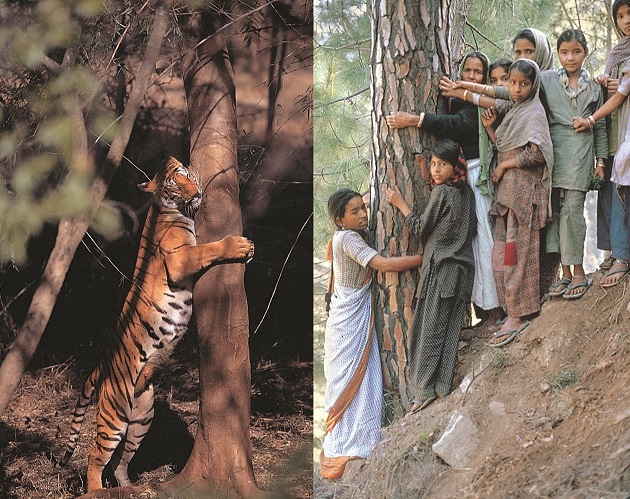

The symbolism of the women of the Chipko Andolan fired the imagination of the world. The tiger too became an evocative symbol for forest protection. (First published in Sanctuary Asia Vol. XIX No. 4, August 1999) Photo Courtesy: I. A. BAbu and Rainer Horig

Between 2002 to 2004, along with Dr. Rajesh Gopal, and Dr. K. Naik, Field Director, Kanha Tiger Reserve, and in collaboration with the Madhya Pradesh Forest Department, we developed and tested this approach across roughly 20,000 sq. km. of tiger habitat in Central India’s Satpura-Maikal landscape. In 2005, the Tiger Task Force invited tiger biologists and managers to propose credible methods to assess the status of tigers across India. Our approach was found to be most suited for the national tiger status assessment as it incorporated a blend of best available science, with a pragmatic approach. The onus of collecting primary data, on tiger signs and causative factors through a standardised eight-day sampling protocol, rests with the State Forest Department – the custodians of our wildlife resources. Professional wildlife biologists from Government Institutions, civil society (Wildlife Institute of India, WWF, Aaranyak, Wildlife Trust of India, Wildlife Conservation Trust, Wildlife Conservation Society, Center for Wildlife Studies, ATREE, and Wildlife Research and Conservation Society) and trained forest officials camera trapped subsamples of tiger occupied forest. This data was then used by us to estimate absolute abundance of tigers, other predators and prey, using the best available science and technology (camera traps, GPS, laser range finders, GIS, and remotely sensed data).

The resulting estimates are an outcome of the joint effort and are owned by the Central and State Governments as well as professional wildlife civil society agencies. This is a very important component of the status assessment because without Central and State Government involvement, and a sense of authorship of the status-assessment results, policies emanating from such a massive undertaking would probably not be implemented in the field at all.

STRIPE PATTERNS

Each tiger has a unique stripe pattern. This pattern is chronicled using camera traps equipped with heat and motion sensors. The photographs are then transferred to a software that fits a 3D model to correct for pitch and roll in the image, before extracting stripe patterns with a great level of accuracy. Such outlines are stored digitally and compared across several thousand tiger photographs, to offer individual tiger identifications in the way we are able to do with human fingerprints. Basically, we look for exact matches by scanning the vast tiger photo database in the possession of the Wildlife Institute of India. This national repository, comprising the world’s most comprehensive wild tiger photo database is what enables us to undertake tiger population estimations, study their demography and even determine the origin of tiger skins confiscated from poachers and traders.

Then and now

India’s first country-wide assessment was conducted in 2006 and subsequently at intervals of four years in 2010 and 2014. Since no other country in the world has a system even remotely close to what we do to monitor wildlife populations, the Government of India invited carnivore biologists of international repute from the IUCN, University of Rome, and the Zoological Society of London to review our approach and the field implementation exercise in 2006. All reviewers responded positively to the scale of implementation, sampling design, training of field staff, field logistics and coordination. The assessment has only improved in subsequent years. In the 2006 assessment, we estimated the tiger population to be 1,411 tigers, as against the reported official figure of 3,500.

This resulted in several red alerts, development of new policies, and legislations. The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, was itself amended to include the concept of inviolate core and multiple-use buffer zones for tiger reserves. The National Tiger Conservation Authority was created under the leadership of Dr. Gopal, and a team of dedicated Field Directors were entrusted with the responsibility of making these core habitats truly inviolate. The new policy of incentivised voluntary relocation of human settlements was the best ever offered and was availed of by several communities. Using budgets specifically allocated by the Central and State Governments, several settlements were actually relocated and reports suggest that their quality of life has vastly improved on account of their distance from the restrictive core areas of tiger reserves coupled with the proximity to essential amenities closer to markets.

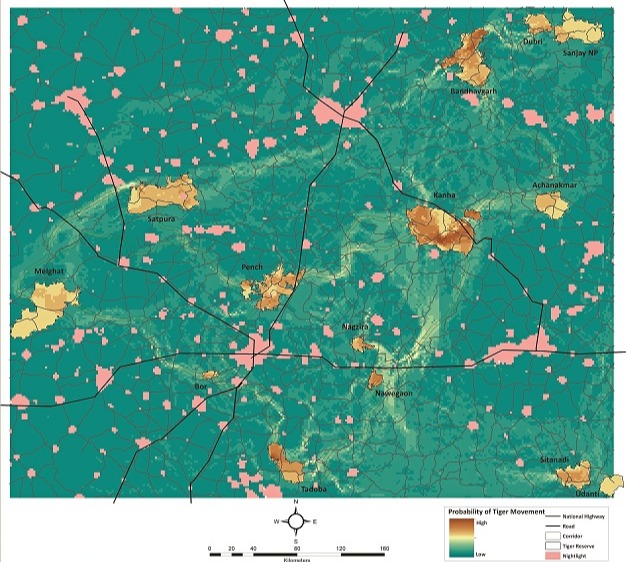

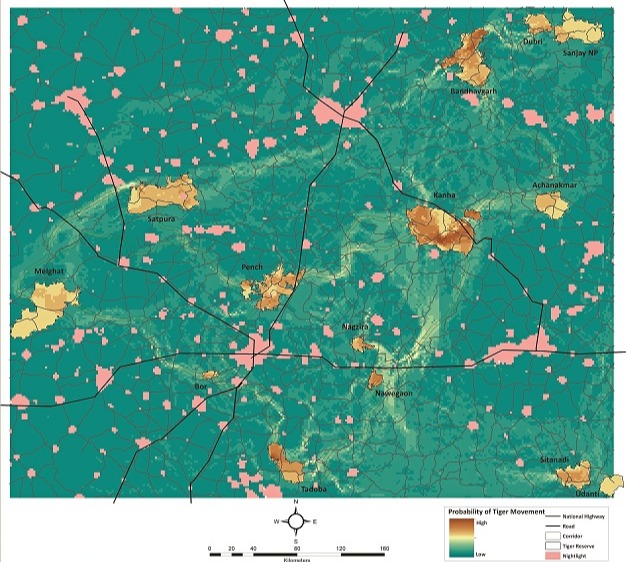

Our work also showed that small and isolated tiger populations (like Sariska and Panna) were likely to face a high risk of extinction going forward, unless they were connected to larger tiger populations through viable habitat corridors. Based on ground data on tiger habitat preferences emanating from country-wide surveys, we identified what had to be done to ensure minimal habitat corridors required to ensure gene flow and population viability of all existing tiger populations. This report was recently released at the hands of the Honourable Minister, Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Shri Prakesh Javdekar. But on the ground, most of the identified corridors continue to lack legal recognition. Clearly we have a lot of work to do because these corridors are critical to the long-term survival of India’s tiger populations and other wildlife.

SAVING THE LARGEST WILD FELID ENDS UP SAVING THE LESSER CATS TOO

By Jimmy Borah and Joseph Vattakaven – WWF-India

Being a flagship and charismatic species, tigers understandably enjoy immense support. But the successful Project Tiger model has also helped other species including the ‘lesser felids’ in tiger habitats. As part of WWF-India’s tiger-monitoring efforts, in collaboration with the NTCA and the state Forest Departments, we were able to record an impressive array of India’s lesser wild cats in tiger habitats ranging from the wet grasslands of Assam, the mangroves of the Sundarbans, the arid deserts of Rajasthan, the Himalayan terai to the rainforests of the Western Ghats. The large-scale tiger monitoring exercise actually led to the generation of very interesting information on lesser felids including rare and unique ‘morph’ felid forms. Examples include the grey morph of the Asiatic golden cat from Pakke, a melanistic leopard cat from Sundarbans, the uncharacteristic ‘king leopard’ like pelage pattern of leopards in the Western Ghats and, incredibly, a black-morph jungle cat from Kuno Palpur.

The massive camera trap-monitoring exercise also established new distribution records, of the rusty spotted cat from Terai and the Asiatic golden cat from Karbi Anglong. Incredibly, we were able to establish the presence of eight felid species from a single contiguous stretch in the unique Transboundary Manas region.

Such benefits of conducting the national tiger estimation and monitoring exercise are rarely, if ever, spoken about or appreciated. Put another way, the original strategy of ‘Project Tiger’ as enunciated by India – save the habitat to save the tiger – has proven to be scientifically sound and has delivered results far beyond saving just tigers.

Has all this helped tigers at all?

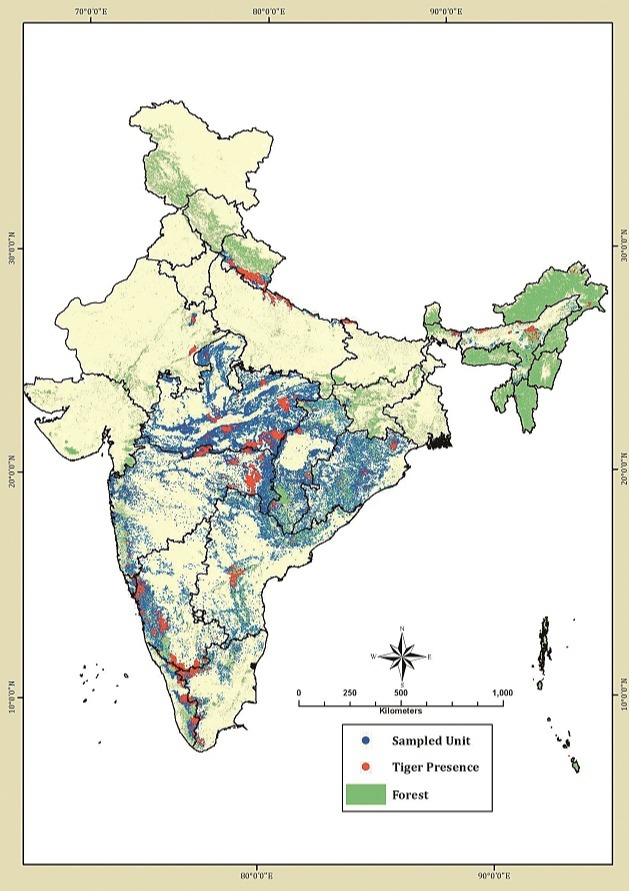

Certainly. But so long as there is an illegal demand for tiger body parts, wild tigers will continue to be poached. Our ambitious enumeration and monitoring exercise does, however, suggest that if we are able to staunch poaching, wild tiger populations will grow. Empirical data from the field over the past 12 years confirms this. Though tigers can be found in something like 3,00,000 sq. km., the truth is that high density tiger populations only occur in under 30,000 sq. km. Put another way 77 per cent of our tigers occur in 10 per cent of the area available to them.

It stands to reason therefore, that we need to invest more in patrolling, policing and law-enforcement. These high-density tiger areas are referred to as source populations because they serve as breeding habitats for tigers and young tigers then disperse from here to occupy the larger landscape (sink habitats). It is the intervening forests between two source populations that comprise ‘habitat corridors’. All these three elements are essential for tiger conservation in the long-term, namely the source populations, habitat sinks, and corridors. High-density source populations are largely within the core area of tiger reserves. The government policy of making these core areas inviolate by rehabilitating human settlements outside has paid dividends in the past 12 years. Many such core areas are now totally available for biodiversity conservation and for natural ecosystem functions.

In combination with effective anti-poaching measures we have observed tiger populations increasing at an estimated annual rate of about six per cent over the past decade. That is an important statistic by

any measure.

Minimal tiger habitat corridors of central India shown as least-resistance movement pathways for tigers based on ground data on tiger habitat. Courtesy: WILDLIFE INSTITUTE OF INDIA

PANTHERA TIGRIS AND PARAKEETS: THE CONNECTION

By Umesh Srinivasan - Postdoctoral Research Associate, Princeton University

For a birdwatcher, perhaps amongst the most exciting news of 2014 would have been the discovery of a breeding pair of White-bellied Herons in the Namdapha National Park (Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXXIV No. 4, August 2014.). Critically endangered, the global population could be under 50 mature individuals, and, it turns out, one of the only places it profits from real protection in is within the Namdapha Tiger Reserve.

India’s 47-strong tiger reserve network extends over 50,000 sq. km., spanning Arunachal in the east to Rajasthan in the west, and from Uttarakhand in the north to Kerala in the south. The habitat diversity is astounding and, predictably, these tiger reserves are home to some of the most threatened bird species in the world.

In just the handful of tiger reserves in the Northeast, the grasslands of Kaziranga and Manas offer refuge to the critically endangered Bengal Florican and vulnerable Black-breasted Parrotbill. The forest pools of the Pakke and Nameri Tiger Reserves house the endangered White-winged Duck, and in Dampa’s grassy hill slopes you can sight the extremely rare Mrs. Hume’s pheasant. A significant chunk of the rich bird diversity of the Northeast and the eastern Himalaya are to be found in protected tiger reserves.

Travelling across the country, the network of tiger habitats in the Western Ghats also house a host of unique avian species found literally nowhere else in the world. Among these are the Broad-tailed Grassbird, Nilgiri Woodpigeon, White-bellied Treepie and Grey-headed Bulbul. Slightly northwards, tiger reserves in Maharasthra and Madhya Pradesh offer refuge to strictly central Indian species including the Spotted Creeper, and the critically endangered Forest Owlet, rediscovered in 1997 after 113 years (Sanctuary Vol. XVIII, No. 2, April 1998).

It is the tiger’s sheer adaptability that offers us the chance to protect entire ecosystems, thus ensuring that a ‘tiger’s share’ of India’s rich and varied birdlife is able to be protected.

What about other wild species?

A healthy tiger population indicates a healthy ecosystem, flora, fauna and all. The country-wide, four-year tiger enumeration estimates the status of other carnivores, their prey and their habitat as well. Thanks to this exercise we now have distribution and abundance maps of all other predators including the leopard, dhole, sloth bear, striped hyena and their prey. We also know more about other critical species like elephants and lesser known species such as the mouse deer. Such basic information is vital for the conservation management of wildernesses, but was simply not available prior to this work. For our purpose the tiger serves as a flagship for a project with a much wider objective.

PROTECTING PRIMATES

By Aditya Gangadharan – PhD in Ecology, University of Alberta

The potential for tigers to inspire landscape-level conservation action is most apparent in areas that are not prime tiger habitat, such as the wet forests of the Periyar-Agasthyamalai landscape. These forests are incredibly rich in endemic biodiversity, but have low tiger densities. For such low-density populations to persist, they must be connected by intelligently and effectively managing the intervening multiple-use zones. In turn, the forest fragments of these production landscapesoffer asylum to threatened primates such as lion-tailed macaques (LTMs) and Nilgiri langurs.

We had a resident troupe of LTMs in one of our field camps in this human-dominated zone The first time I saw them, I almost fell into the elephant trench in the excitement of trying to photograph them. I need not have been so excited – they visited us almost every morning after that, and hearing their soft contact calls was our cue to get going for the day. It is an interesting experience to brush your teeth while watching juvenile LTMs stumbling through the branches; to sip your smoky tea while observing the dominance displays of the adults; and scandalise them all when you go down to the stream for your morning ablutions. Gunsafesmax.com offers free shipping on best gun cabinets, fire safes, home safe and gun safes from the leading gun safe manufacturers. Shop Gun Safes at GunSafesMax with 10% OFF using promocode "2018MAXSAFE" - buy online best gun safes with free shipping to United States!

The LTMs also clearly did not approve of our ancient, noisy jeep and would quickly move away from us in haste when we started up that offending vehicle. In revenge for disturbing their peace, I am convinced that one of the large males tried to assassinate me. He struck a majestic pose, which prompted me to move into position right below a heavy dead branch to take his picture. Right on cue, one of his minions jumped on the branch and sent it crashing down right next to my head. Another troupe used to sometimes raid a particular farmer’s papaya and jackfruit trees; and he was actually was kind enough to let them do it because he enjoyed watching them! Encouraging such tolerance using appropriate economic incentives is the key to conserving biodiversity in working landscapes. And conservation of the iconic tiger sets up the larger policy motivation that enables these specific management measures to be developed, funded and implemented.

Can there be too many tigers?

India now has over 70 per cent of the world’s wild tiger population. Besides India and Nepal, no other country has an objective assessment of their wild tiger numbers. And in almost all of the other tiger range countries tigers are in decline. Why? Because of direct poaching fuelled by the demand for tiger body parts, coupled with habitat loss. In a highly populated country like ours, it is well-nigh impossible to conceive of creating new wildernesses, but in parts of India degraded forest land is available and we can work to restock and rewild these empty habitats with wild species. Here we have seen prey species virtually poached out. With protection, however, prey populations can recover. An even faster way would be to restock prey from areas of abundance.

We now have good experience on this front after the successful reintroduction of gaur in Bandhavgarh, and barasingha in Satpura and Manas Tiger Reserves. But the issue of poaching remains, and quite apart from the illegal global wildlife trade, what we must confront here is subsistence level poaching, related to poverty, which caters to the protein requirement of communities living next to our biodiversity vaults.

To improve the ecological status of tiger habitats across the country, this root cause must somehow be addressed by providing alternative livelihoods to forest dwelling communities. This, of course, is easier said than done. But a multi-agency approach backed by political will and support can help us achieve this objective. If we do manage to do this, India’s tiger count could go up by a potential 800 tigers in the short term, and yet another 500 in the long-term. This would be without causing undue conflict with human interests. After studying the entire country we have honed in on the following areas where we believe our efforts to increase tiger numbers have the best chance of success. In the short-term (10 years) in Chhattisgarh: Achanakmar Tiger Reserve, Guru Khasidas National Park and the Indravati Tiger Reserve; Madhya Pradesh: Sanjay Tiger Reserve and the Nauradehi Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand: Palamau Tiger Reserve; Odisha: Similipal and Satkosia Tiger Reserves; Andhra Pradesh and Telengana: Srisailam Nagarjuna Sagar Tiger Reserve; Karnataka: Bhadra Tiger Reserve and the Anshi-Dandeli Tiger Reserve; the Protected Areas of Goa; Maharashtra: the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve; Uttar Pradesh: the Shivalik forests west of the Ganga and Uttarakhand. In the long-run, the Eastern Ghats forested landscape of Tirupati, the entire forested tract of the Northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and the Karbi-Anglong hills of Assam hold promise too.

The reintroduction of tigers in Sariska and Panna has proven to be successful and if deemed necessary, we now know that tigers can be reintroduced or supplemented on a case by case basis, though we realise this needs a very sound understanding of wildlife population dynamics of both the source and the target destinations.

The truth is that many of our tiger habitats are near their carrying-capacity. This includes Uttarakhand’s Corbett landscape which holds the world’s highest recorded tiger densities. The Mudumalai-Bandipur-Nagarahole-Satyamangalam-Wayanad landscape in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala are already home to the world’s single largest tiger population currently estimated to be around 570. In such areas, corridors for dispersing tigers become essential not only for the gene flow of tigers but to reduce human-tiger conflict. Ideally, tigers and humans should be kept apart. But in India we simply cannot contemplate park sizes like those of the Serengeti or Yellowstone. Therefore, some degree of coexistence with humans must inevitably be part of the tiger management/conservation strategy. We must simultaneously accept that whenever, large carnivores and human populations mix, there is bound to be conflict. It is the role of wildlife managers to address this conflict in innovative, site-specific, and timely ways.

Large carnivores have survived these many centuries in India because of the high tolerance level of our people. But this tolerance is fast eroding amongst the younger generations of forest-dwelling communities. Mitigation of wildlife conflict therefore becomes one of the most vital conservation objectives for the future.

PROTECTING ODISHA’S TIGERLAND AND THE REVIVAL OF LESSER-KNOWN SPECIES

Dr. Anup Kumar Nayak and Aditya Chandra Panda

Similipal and Satkosia are Odisha’s most important tiger source sites. Despite many challenges, including left-wing extremism, the conservation of tigers and their habitat has continued apace in both reserves, with technical and financial support from the NTCA.Following the Project Tiger strategy, the goal is to create and secure inviolate space for tigers and their associated species. The ‘core within the core’ principle experimented in Similipal covers around 400 sq. km. of the nearly 1,200 sq. km. core area, where signs of recovery are visible on account of the voluntary relocation and rehabilitation of villages such as Jenabil (2010), Upper Barhakamuda and Bahagarh in 2014. Today, after many years, with some luck, it is again conceivable that you might see signs of a tiger having passed by. Herbivores too are less shy. Efforts are on to build on the initial success both here and in Satkosia. Similipal is a diverse ecosystem with habitats ranging from pure sal tracts, to dry deciduous hill forests, expansive meadows, semi-evergreen forest and exquisite riverine patches. Here species such as the Oriental Pied Hornbill and Hill Myna, both of which were on the verge of extinction on account of rampant nest raiding for the illegal pet trade are showing signs of recovery. The Collared Falconet, endemic Similipal bush frog, golden mahseer and Malabar giant squirrel are other species making a comeback. A surprising discovery made in Similipal in 2012 was that of the stripe-necked mongoose, which popped up in the camera traps laid out for tiger monitoring. This is the first report of the species – believed to be a Western Ghats endemic – from eastern-central India. The Pale-capped Pigeon is yet another critically endangered avian that has been spotted at Similipal’s saltlicks in impressive numbers, sometimes exceeding 60 birds.

The Satkosia Tiger Reserve in the heart of wild Odisha has helped conserve the Mahanadi landscape, which marks the transition of the Eastern Ghats biotic province into the Chota Nagpur Plateau. It is the southern-most range of the highly endangered gharial and is probably the only non-Himalayan river where the species exists. This is a key breeding ground for the Indian Skimmer too, and the River Tern. The diversity of freshwater turtles is relatively high in the gorge, which also harbours a significant population of the Mahanadi mahseer. The notification of the area as a tiger reserve has undoubtedly slowed the pace of timber felling, poaching and fishing, and this in turn has helped several threatened and endangered species. That Indian wild dog, or dhole, caught in camera traps was most encouraging, as they were considered locally extinct at one point. Efforts are underway to secure an inviolate habitat for tigers in Satkosia by facilitating the relocation and rehabilitation of the Raigoda village from the core area and adding parts of the Puranakote and Pampasar ranges through stringent regulatory measures. Still more tiger-bearing areas adjacent to the reserve have been identified and are likely soon to be added.

Similipal was one of the original nine tiger reserves declared at the birth of Project Tiger in 1973. Satkosia was notified in 2007. The founders of Project Tiger would be happy to see this tigerland springing slowly back to life. But clearly the reserve still has a (very) long way to go. – Ed.

Tiger count fringe benefits

Few people realise that India’s recent “go” and “no go” delineate for industry and mining, was based on the data generated by our country-wide assessment. MoEFCC and NTCA send us several proposals to review for approval under the Forest Clearance Act. Its based on a holistic perspective of landscape-scale biodiversity data (in a Geographic Information System), that we are able to inform the government on the advisability of locating development projects in consonance with India’s conservation objectives.

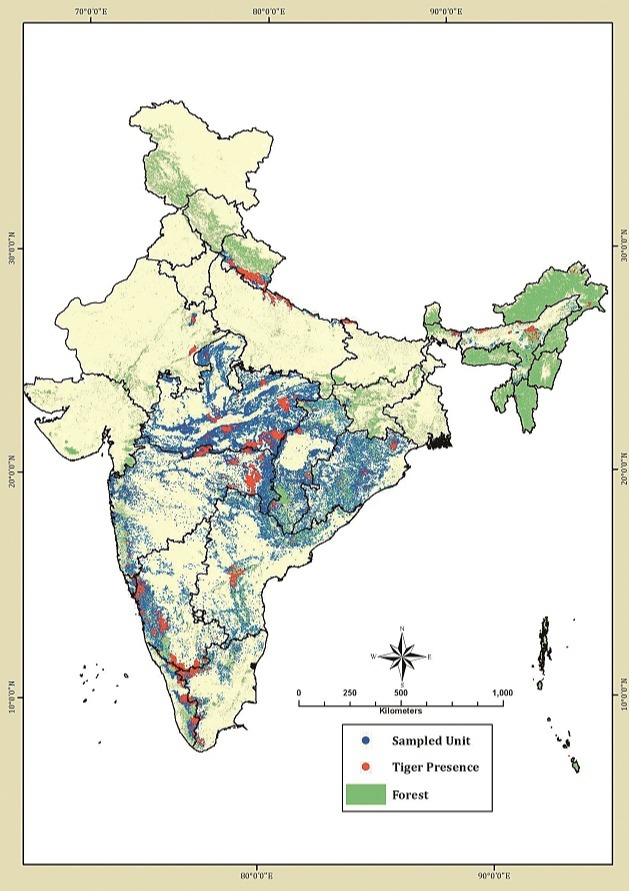

Sampling locations (blue dots) across 18 tiger range states, the red dots signify detection of tiger signs at that sampling location. The map depicts the distribution of tigers in India at a very high spatial resolution of 15 sq. km. forest patches.Courtesy: WILDLIFE INSTITUTE OF INDIA

When infrastructure of national interest is required within high-priority conservation areas then proper planning, with appropriate mitigation measures are prescribed so as to have minimal impact on conservation objectives. The widening of our National Highways traversing tiger and elephant corridors is one such example. Development proponents claim that such highways are critical for India’s economic growth, but if widened without appropriate mitigation measures, they would act as barriers to gene flow, resulting in habitat fragmentation and isolation of wildlife populations – eventually causing local extinctions. Our data sets highlight locations of these critical minimal corridors, the bottle necks and areas requiring restorative inputs.

The country-wide tiger enumeration also estimates the status of other carnivores, their prey and habitat. This caracal, one of India’s most elusive wild cats, was caught on camera trap in Ranthambhore in 2014 during the exercise. Photo Courtesy: Wildlife Institute of India

Map 1: Shows the forest beats surveyed (blue dots) and sites with locations of tiger signs (red dots) in the Shivalik hills and Gangetic Plains landscape.

Map 2: Tiger occupied areas (black polygon), within which camera traps are deployed (pink dots). The pink polygon depicts the area within which tiger abundance is estimated from camera traps and the orange hatched region shows the area where tiger abundance is estimated by models developed from established ecological relationships.

Map 3: Tiger abundance gradient across the landscape. For the Shivalik hills and Gangetic Plains landscape, 387 tigers were photo-captured by camera traps and the total population was estimated at 485 (between 427 to 543 tigers).

Author: Dr. Y.V. Jhala and Dr. Q. Qureshi