A Failed COP27 Commits To Loss And Damage

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 12,

December 2022

Text and Photographs by Shailendra Yashwant

The 27th conference of parties (COP27) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) finally closed in the wee hours of November 20, 2002, with a ‘breakthrough’ agreement to provide ‘loss and damage’ funding for vulnerable countries hit hard by climate disasters, sending a cheer among the delegates from island nations, vulnerable countries and civil society organisations, while also giving a lease of life to a multi-lateral process that has otherwise left the world on the brink of a climate catastrophe.

Creating a specific fund for loss and damage has been a longstanding demand of those who are least responsible and worst impacted by climate change, and its announcement marked an important point of progress, for climate justice as well as pinning responsibility on the historical emitters.

Disha Ravi with the youth delegates from Fridays for Future and other youth organisations at the Climate March. For the first time, youth were provided with a dedicated space at COP27 to host dialogues and discussions aimed at accelerating global climate action.

A bittersweet win, because the COP failed in garnering commitments from nations to increase their emission reduction actions, aka Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to limit global temperature rise to 1.50C as pledged by all countries in the Paris Agreement.

Rich Against Poor

This is a dangerous failure – science requires almost halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 – but the implementation of current pledges of NDCs put the world on track for 2.50C by the end of the century. The world is already experiencing the impacts of nearly 1.20C of warming; the floods in Pakistan a fresh grim reminder of what awaits all countries in the future. And yet the COP Presidency could not push countries into upping their ambition or putting a realistic roadmap for a mitigation programme.

Instead, governments were requested to revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their national climate plans by the end of 2023, as well as accelerate efforts to phasedown unabated coal power and phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. This is a joke, and actually shows the lack of political will in the developed countries to accept that oil and gas are also fossil fuels and there is no such thing as an efficient fossil fuel subsidy. After India raised the issue, there was initial support to the inclusion of all fossil fuels in the cover text, but oil-rich countries and their friends in the developed countries made sure the idea was shelved.

Debashish Kumar, MLA from Kolkata, announced the intention of making the city carbon-neutral at a Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) event during COP27.

In another big fail, the COP was not able to come up with long-awaited answers to a question on every developing world delegate’s lips as to how and when the developed world will start paying out the full 100 billion dollars per annum climate finance goal announced in Copenhagen in 2009.

The UNFCCC calculated that developing countries would need USD 5.6 trillion up to 2030 to fulfil even the current NDCs. Even the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, the cover decision of COP27, clearly states that a global transformation to a low-carbon economy is expected to require investments of at least four to six trillion USD a year.

The failure of the rich and developed countries to come good on their promise is not only a matter of serious concern for the effectiveness of the COP presidency, it also raises doubts on the integrity of the announcement on Loss and Damage funds if countries are not willing to put their money where their mouth is.

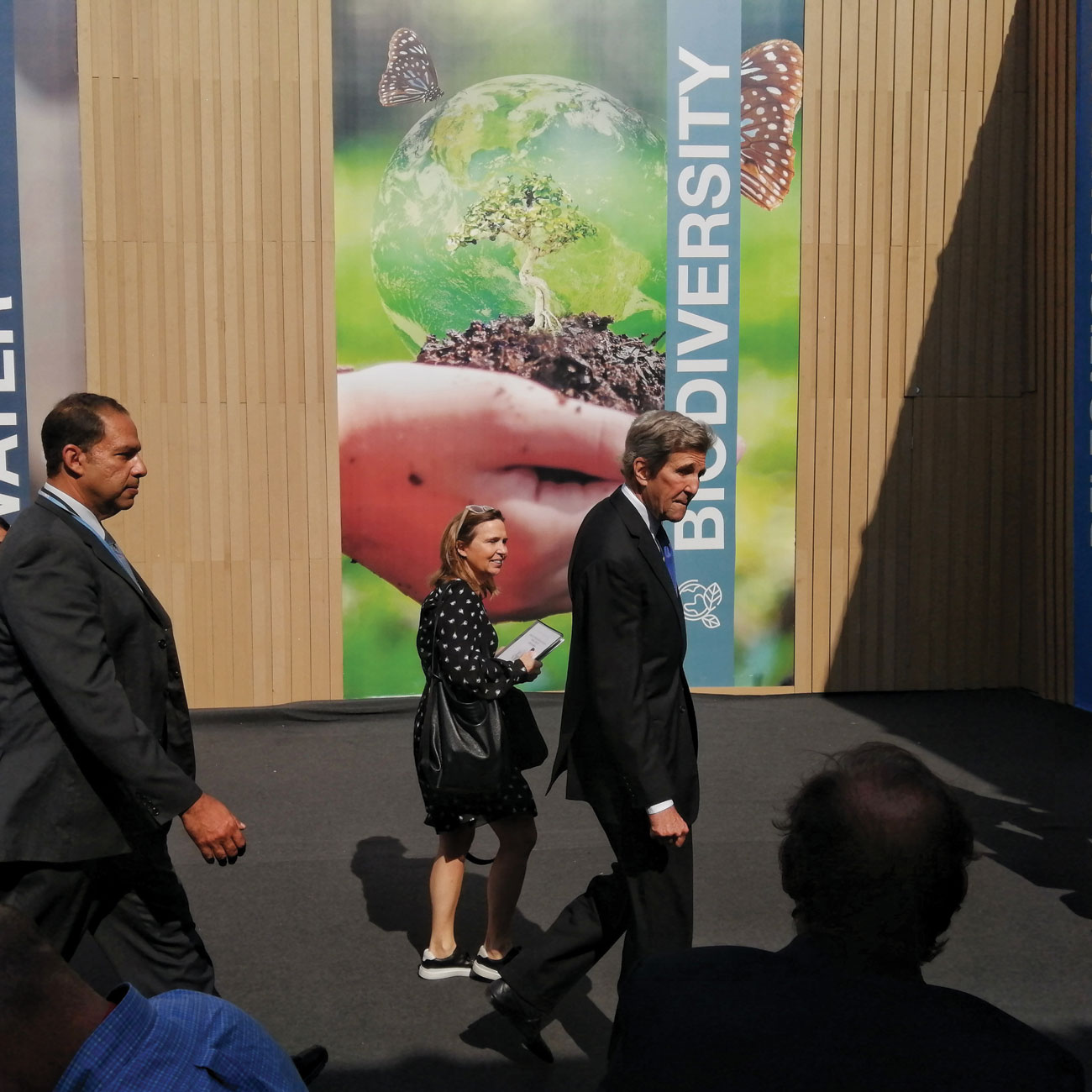

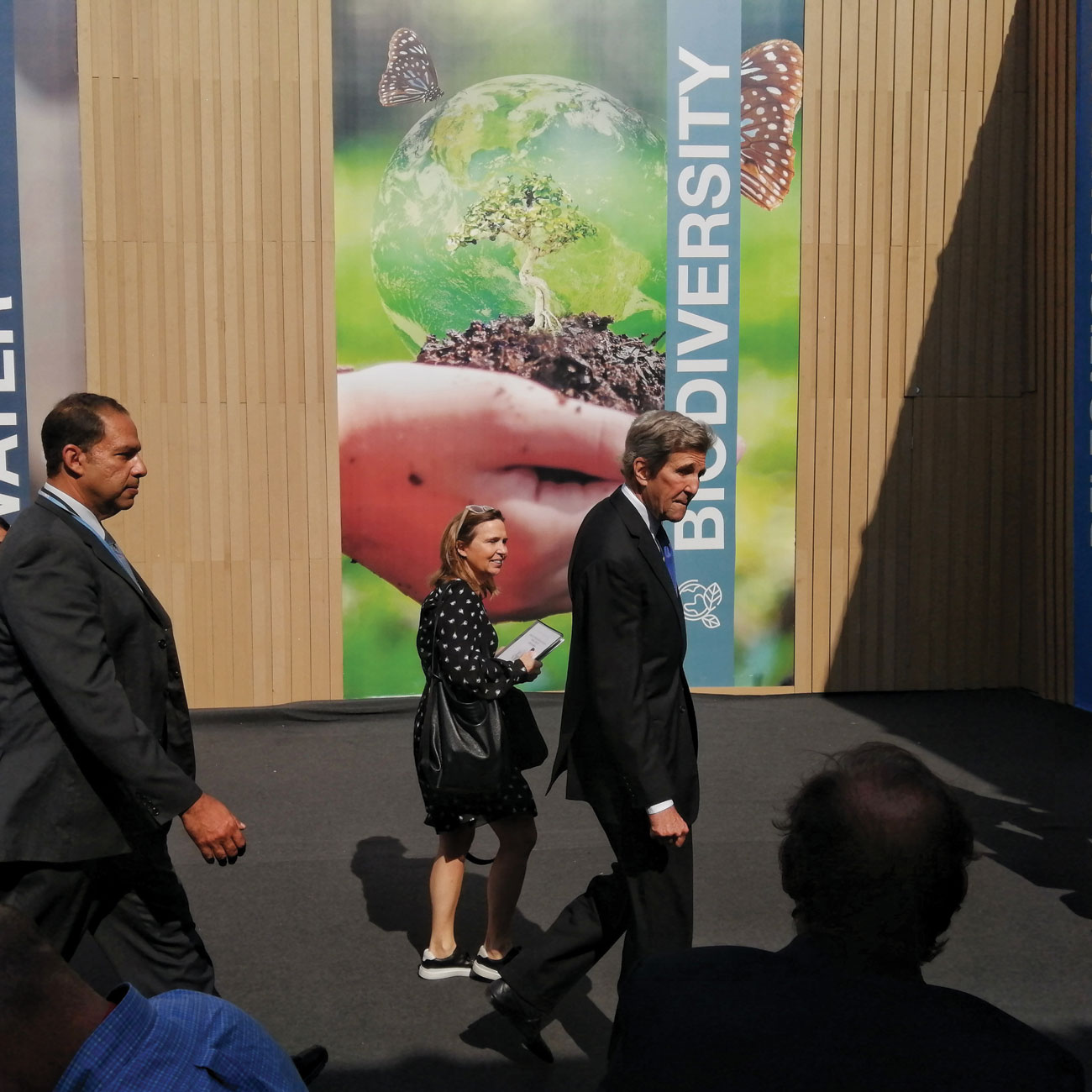

John Kerry, climate envoy of USA, is known as a rock star of climate diplomacy but has not been able to convince his own country, let alone others, to accelerate the phase out of all fossil fuels.

Business As Usual

Set against a difficult geopolitical backdrop, COP27 brought together more than 35,000 participants to share ideas and solutions, and build partnerships and coalitions. Indigenous peoples, local communities, cities and civil society, including youth and children, showcased how they are addressing climate change and shared how it impacts their lives.

Many of the ideas showcased in the country and NGO pavilions were about adaptation and building resilience to impacts of climate change, like restoring mangrove swamps and regrowing forests, measures that require funding that the poor countries do not have. Of the 100 billion dollars a year, rich countries promised they would receive only about 20 billion dollars, which would go towards adaptation. In Glasgow, countries had agreed to double that proportion, but at COP27 some sought to remove that commitment that was later reinserted in the final text thanks to a feisty pushback by developing countries.

No progress was made on forest protection at COP27 except for the launch of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership, which aims to unite action by governments, businesses and community leaders to halt forest loss and land degradation by 2030. At COP26, more than 100 countries signed a declaration to end and reverse deforestation by 2030. The funding promises of almost 20 billion dollars toward forest conservation were equally ground-breaking. Last month, The Forest Declaration Platform released its latest progress report on the global goal of ending and reversing deforestation by 2030. It found that not one global indicator showed us to be on track toward these goals. The deforestation crisis has actually worsened. Deforestation in the Amazon, for example, increased by 48 per cent over 2021.

There can be no climate justice without human rights and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights was the main call of the People’s Declaration for Climate Justice, which includes demands to decolonise economies and societies, repay climate debt, and address global warming by reducing emissions to zero by 2030.

Another UNEP report shows that financial commitments needed to meet deforestation goals, known as the Green Gigaton Challenge, are way off track. The Green Gigaton Challenge aims to mobilise funding to reduce one gigaton of emissions from tropical deforestation by 2025, and a gigaton each year thereafter until 2030. The report revealed that less than a quarter of the finance needed to meet the goal has been mobilised to date.

“There will be no climate security if the Amazon isn’t protected,” said Lula da Silva, the incoming President of Brazil at a side event at COP27. Without giving details, he said his administration would work with the Congo and Indonesia, along with Brazil – home to the largest tropical forests in the world. Given the moniker “OPEC of the Forests,” the general idea is for the three countries to coordinate their negotiating positions and practices on forest management and biodiversity protection. Lula also argued that the UN climate summit in 2025 should be based in the Amazon, so “people who defend the Amazon and defend the climate get to know the region close up.”

On account of restrictions on freedom of association and assembly, and free speech imposed by the Egyptian government in the streets of Egypt, for the first time ever, the Climate Movement’s Global Day of Action´s big march took place within the Blue Zone (governed by UN rules).

Where Do We Go From Here?

In another side event at COP27, the Mangrove Alliance for Climate (MAC) was launched on November 8. An initiative led by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Indonesia, MAC includes India,

Sri Lanka, Australia, Japan, and Spain. The move, in line with India’s goal to increase its carbon sinks, will see our country collaborating with Sri Lanka, Indonesia and other countries to preserve and restore the mangrove forests in the region. However, the intergovernmental alliance works on a voluntary basis and the parties will decide their own commitments and deadlines regarding planting and restoring mangroves.

All eyes are now on the upcoming COP15 UN Biodiversity Conference in December, some are dubbing it as a final opportunity for the world to turn the tide on nature loss, in support of climate action. In fact, the champions of the Paris Agreement have asked that leaders secure a global agreement for biodiversity which is as ambitious, science-based and comprehensive as the Paris Agreement is for climate change.

COP27 failed to deliver on people’s expectations for swift and timely climate action at a time of poly-crisis. Its one success, the breakthrough Loss and Damage deal, was actually a no-brainer. If countries cannot mitigate, rest assured there is going to be loss and damage. Having a fund to help the worst affected is a good idea, but wouldn’t it be better to reduce emissions and thereby reduce loss and damage as much as possible? Where is the money going to come from, anyway?