The Great Vanishing

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 6,

June 2022

By Mihir Godbole, Dr. Abi Tamim Vanak, Iravatee Majgaonkar & Nikita Sabnis

“Grasslands are the ‘common’ lands of the community and while there have been robust traditional institutions ensuring their sustainable management in the past, today, due to take-over by government or breakdown of traditional institutions, they are the responsibility of none. They are the most productive ecosystems in the Indian subcontinent, but while they belong to all, they are controlled by none. Indeed, they are often looked at as ‘wastelands’ on which tree plantations are carried out, or which can be easily diverted for other uses. Such diversions often put even more pressure on adjoining ecosystems for grazing and fodder removal, resulting in a cascading chain of degradation.”

– Report of the Task Force on Grasslands and Deserts submitted in 2006 to the Planning Commission of India.

A chinkara herd grazes cautiously as a lone wolf surveys the landscape on the outskirts of Pune, Maharashtra. Wolves, chinkara, blackbuck, and ground-dwelling birds like lapwings, coursers, sandgrouse and larks are the ubiquitous denizens of this complex rich ecosystem. Photo: Prasad Navale.

I scanned the sparse landscape around me and saw small groups of delicate chinkaras, an occasional black-naped hare, and a pair of mongooses on their morning hunt in the vast stretches of grassland. In 2008, I (Mihir Godbole) visited Diveghat, a place known for its diversity of birdlife, located 40 km. to the south of Pune. It was winter and, true to its reputation, the place was bustling with migratory birds such as stonechats and wheatears as well as local birds such as shrikes, sandgrouse and coursers. It was like being in a sanctuary populated with wild creatures. The mud track led through a network of undulating hills and opened out to a grassland on top of a hill. I stopped short, awestruck by the sight in front of me. A pack of five wolves… basking in the morning sun. They watched closely as I drove a bit closer, and seemed unperturbed, yet alert. Halting at a comfortable distance, I was treated to the unforgettable experience of spending the best part of the day with the wolf pack.

As I watched them rest, groom and, briefly, chase away a free ranging dog that came too close, I wondered at the way nature worked. Not red in tooth and claw as hunters of yore projected nature, but well-adapted, content and at peace with a world they have occupied far longer than we have.

At sundown, the pack left in the direction of a dhangar (shepherd) camp at the base of the hill. Intrigued, I followed them but they had vanished into the wilderness. Long conversations with the shepherds revealed that they had been living with these wolves for years. It was an age-old relationship built on tolerance, acceptance and trust.

Over the years, I have spent considerable time documenting the region’s wildlife and made it my life’s mission to champion grasslands, perhaps the least understood and valued of natural habitats on the Indian subcontinent. It was this inner calling that led to me setting up the Grasslands Trust in 2019, with the objective of enhancing the welfare of grassland-dependent communities by learning from them and protecting grassland ecosystems with their involvement and help.

Economic Importance of Grasslands in India

Millions of pastoralists have been dependent on grasslands for millennia for the fodder needs of their livestock. These livestock in turn provide products like meat, wool, and leather. Livestock production is the backbone of Indian agriculture, contributing four per cent to national GDP and providing employment and livelihood to 70 per cent of the population in rural areas. Around 30 pastoral communities in semi-arid hilly regions in northern and western parts of India, as well as 20 in temperate hilly regions depend on grazing-based livestock production. Although there are no official figures of practising pastoralists in India, the number is believed to be close to 13 million. It is also estimated that 53 per cent of India’s milk and 77 per cent of meat production comes from extensive pastoralism that is herding animals in grasslands and forests. Movement based pastoralism being a low-intensity livelihood, has great potential in being compatible with biodiversity conservation. However, it is not recognised as a separate management system by our government and remains marginalised (Kishore and Kohler-Rollefson 2020).

India’s Diverse Grassland Habitats

Grasslands are among the most ancient and diverse Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs) found in India. Scientific evidence suggests that grasslands evolved around eight to ten million years ago during the Late Pliocene period. The ecosystems expanded in hotter and drier climates, after the Pleistocene ice age and eventually evolved to become the most dominant land feature in the whole world. Following that most vital of survival strategies – adaptability – grasslands evolved into diverse types based on the climatic and biogeographical conditions of each region.

Predictably, unique species of flora and fauna co-evolved with the diverse grasslands that adorned our planet. India has been blessed with a mosaic of different biogeographic conditions, and, consequently, an astonishing variety of grasslands. This includes the Trans-Himalaya, where alpine pasture meadows colonised elevations above the natural limit of forest and scrub vegetation. These grasslands clothe roughly 25 per cent of the Indian Himalaya (Lal et al. 1991) and are characterised by very low primary productivity, with short seasonal growth in summer. In India, the Trans-Himalaya is located at the junction of three biogeographic realms – Palaearctic, Ethiopian and Oriental and, not surprisingly, biological elements of all these realms are to be found here. A large-herbivore assemblage, with their attendant predators, evolved in this ‘hostile’ environment down the ages, including Himalayan blue sheep, Ladakhi urial, snow leopards and Himalayan wolves. The meadows also provide local communities, including Gaddis and Gujjars – semi-nomadic pastoralists who have been breeding buffaloes, goats, sheep and camels for generations – with grazing pastures.

Nomadic shepherds, the Dhangar community has lived closely with the wildlife of open savannahs, including wolves and leopards, for ages. Despite the threats to their livestock, the community has a respectful relationship based on trust and acceptance of their wild neighbours. Photo: Pratik Joshi.

South-west of the Himalaya, in the arid, low-rainfall regions of Kutchh in Gujarat, lies another type of grassland in Banni. One of the largest biodiverse grasslands in Asia, spanning 2,497 sq. km., the rich floral and faunal diversity has quite literally defined the cultures of the hardy communities that have lived here for generations. Recent studies reveal that along with climatic factors such as rainfall, anthropogenic influences such as fire and herbivory have also shaped the present nature of the Banni grasslands. Here, the vegetation is sparse and highly dependent on annual rainfall variations, with the ecosystem dominated by saline-tolerant grasses, scattered tree cover and scrub. Half of Banni is now a Prosopis dominated woodland. Nilgai, chinkara, blackbuck, wild pig, golden jackal, black-naped hare, Indian grey wolf, caracal, Asiatic wild cat and desert fox are all to be found here. The extensive grass habitat also supports the endemic spiny-tailed lizard and an impressive diversity of migratory avians that arrive each monsoon, when the dry grasslands of Banni become more verdant and when depressions turn into living wetlands.

The southern Western Ghats are home to shola grasslands. These “forest-grassland mosaics” or “sky-islands” are tropical montane forest patches separated by undulating grasslands. In existence for over 20,000 years, the sholas are home to an incredible diversity of threatened, endangered and endemic species. In fact, new species are being discovered almost every year. For some time now, however, destructive land-use patterns and invasive plant species such as eucalyptus and acacia have disrupted the native and endemic biodiversity of these ecosystems. Several rewilding efforts are currently ongoing with the help of local communities that look after native-plant nurseries stocked with grassland and shrub species.

The high altitude alpine meadow grasslands of the Trans-Himalaya harbour a diversity of wildlife that evolved to live in these harsh conditions. Blue sheep, or bharal, seen here on the grassy slopes of Kibber in Spiti, are not yet endangered, but face the dual threat of poaching for meat and competition with livestock for grazing grounds. Photo: Suman Mallik.

Indian Peninsular Grasslands

The savanna grasslands in the semi-arid region of the Deccan plateau, in Maharashtra, are the focus of our work at the Grasslands Trust. Here, charismatic predator species such as the Indian grey wolf and the striped hyena live in close proximity with locals, including nomadic pastoralists. Diverse wildlife is also to be found here, including the golden jackal, Indian fox, blackbuck, Indian gazelle (chinkara), Indian pangolin, four-horned antelope or chousingha, and, more recently, the leopard (the acreage of sugarcane fields has expanded in these fragile landscapes). We have also recorded birds such as the Striolated or House Bunting, Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse, Painted Sandgrouse, Indian Courser, multiple species of larks and warblers, predatory birds like Bonnelli’s Eagle and winter migrants including the Steppe Eagle, harriers and Short-eared Owl.

These grasslands are also the only home of the Great Indian Bustard (GIB), a flagship species, currently close to local extirpation. The Thar desert in the north-west and the Deccan plateau of the peninsula were once GIB strongholds. Over the past few decades, however, their populations have dramatically declined, mainly on account of degradation of their grassland habitats, collisions with high tension power lines, changing land-use patterns and depredation by free-ranging dogs. Literally on the verge of extinction, GIBs have been categorised as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the IUCN. Two extant populations remain – one inside the Desert National Park near Jaisalmer, and another in the grasslands and agricultural lands of Pokhran and Ramdeora. Efforts are being made now to breed the birds for eventual release into the wild. For this purpose, several of their erstwhile habitats desperately need to be regenerated to receive the captive-bred birds when they are released into the wild.

Through human history, wild species and local communities have shared grasslands, through a co-evolved, mutually beneficial, relationship. Historically, wolves have had a long socio-cultural association with livestock grazers around the world. The Indian grey wolf Canis lupus pallipes is a subspecies of grey wolf that ranges from Southwest Asia to the Indian subcontinent. It was once widespread across the arid and semi-arid regions of the Indian peninsula in Rajasthan, Punjab and Gujarat to the north, and the Deccan and Coimbatore plateaux in the south. Genetically unique from all other wolves, this species is believed to have evolved from an ancient wolf lineage around 4,00,000 years ago. Current, unverified, estimations suggest that no more than 2,000–3,000 Indian grey wolves survive in India, mainly in Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Karnataka. Some are seen in West Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand, but their distribution has not been well-documented.

The rolling grasslands of the Kudremukh National Park, Karnataka, are among the 34 biodiversity hotspots in the world. This biome in the Western Ghats is the origin of the Bhadra, Nethravati and Tunga rivers, which provide water security to thousands of people and wildlife. Photo: Saurabh Sawant.

Apex predators of the grassland ecosystems in Maharashtra, wolves are gravely threatened by rapidly changing land-use patterns. Expanding agriculture, coupled with linear infrastructure projects including roads, railway tracks, canals and powerlines cut through this undervalued landscape that is being fragmented and degraded almost beyond recognition. Humans are blissfully unaware of their own lethal impacts on a biosphere upon which they are just as dependent as the wild species and ecosystems we trash without a thought. Take the issue of garbage dumping. Across virtually all habitats including grasslands, this has led to the proliferation of dangerously large populations of free-ranging stray dogs that hunt wild species and transmit deadly diseases including rabies, canine parvovirus, tuberculosis, and mange. We recently documented a case of an entire pack of eight wolves going missing on account of an outbreak of the deadly Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) contracted from free-ranging dogs. Wolf pups are particularly vulnerable to this disease.

Wolf populations also face increasing threats from retaliatory killings in the form of pesticide poisoning and den blocking by livestock herders, to ward off livestock attacks. Our team has uncovered numerous cases of wolf dens blocked. Sometimes, wolf pups become unintended victims, when locals smoke them out after mistaking their dens for those of crested porcupines and/or monitor lizards that are hunted for bush meat.

Striped hyenas fare no better. These largely misunderstood creatures are effective scavengers and natural cleaners of these grassland ecosystems. Nocturnal and solitary, they largely feed on carrion, but can be effective hunters too. Their acidic digestive juices can break down even rotting carcasses, but a key source of food in these human-dominated landscapes of Maharashtra is turning out to be poultry waste. Dietary analysis of their scats revealed that 37 per cent of their diet consisted of poultry, and 43 per cent consisted of dogs! Hyenas mark their territories using secretions from their anal gland, distastefully referred to as “hyena butter.” Hyenas make permanent dens in caves and rock crevices that are used by several generations. As is the case with so many unsung wild species, mushrooming new construction projects in these landscapes threaten the habitat of hyenas too.

Photo: Ganesh Mandavkar.

Unique Species of the Indian Peninsular Grasslands

Photo: Ganesh Mandavkar.

Unique Species of the Indian Peninsular Grasslands

Besides large mammals, these landscapes host diverse herpetofauna such as leopard geckos and fan-throated lizards. The leopard gecko

Eublepharis fuscus, a nocturnal reptile, has an unusual feature – it has movable eyelids, unlike other geckos! Consequently, it has a higher visual acuity than other gecko species. Sadly, its charismatic appearance has made it a victim to the illegal wildlife pet trade. Another inconspicuous inhabitant of the grassland ecosystems in Maharashtra is the marbled balloon frog

Uperodon systoma. The species is fossorial, that is, it spends most of the summer and winter months living underground without feeding. Its feet are equipped with specialised tubercles that aid in digging through the soil. They come out to breed during monsoon, when the males gather, engage in territorial fights and call out to attract potential mates. When threatened, these frogs can enlarge their body into a balloon-like shape, appearing much larger than their actual size, to ward off predators. This species lacks teeth, and their diet fittingly consists of termites and ants, which they lap up with their tongue.

The Vanishing

Grasslands are ecologically affluent ecosystems. They provide homes for a wide variety of adapted wild species, provide fodder for livestock, and are also key carbon sinks. And yet, they are one of the most under-valued habitats in India. Decades of exploitation have annihilated vast swathes – many sections have been converted to agricultural fields and overgrazed ecological wastelands. Domestic livestock graze on edible grass species before they scatter their seeds, thus impeding proliferation, growth and regeneration. This enables the spread and domination of unpalatable grass species, thus altering the entire ecosystem, ending up with the reduction of fodder availability for the livestock that caused the slipslide in the first place. Dichanthium and Sehima, edible grass species native to Pune and surrounding regions, are on the decline for this very reason.

Another major threat to grasslands is the well-meaning but poorly designed tree plantation programmes by Territorial Forest Departments in state after Indian state, that ignore the ecological role of grassland habitats, such as the sholas. Exotic trees like gliricidia and eucalyptus have no role to play in the ancient ecosystems in which they have been planted in massive numbers, rendering prime grassland ecosystems unsuitable for wildlife. Ground-dwelling bird species such as bustards and floricans have lost nesting grounds and this predictably and adversely affects their breeding success. That is not all. As such plantations spread, they offer refuge to forest dwelling species like wild pigs and leopards that are literally invited into the proximity of human habitats and into conflict with people. Native faunal species such as the chinkara, Indian wolf, blackbuck and bustard are also threatened, with entire grassland ecosystems being compromised. The trend of unscientific plantation drives organised by self-congratulatory, private NGOs and government departments that plant trees without understanding the ecological repercussions of losing grasslands causes serious disruption in landscapes.

_Velavadar_DSC_0313_SWPA-2020_C-1100_1654499628.jpg)

The Velavadar Blackbuck National Park in Gujarat, a 34.08 sq. km. Protected Area, is a predominantly grassland ecosystem and is home to blackbuck, wolves, jackals, foxes, hyenas, and migratory birds such as theMacqueen’s Bustard, eagles, harriers and larks. Photo: Gyana Mohanty.

Tree plantation sites need to be carefully chosen and kept away from fragile, yet very ecologically vital habitats such as grasslands, because they involve trenching flat lands and Controlled Contour Trenching on slopes to harvest rainwater. All these activities might work well in deforested catchment areas and other degraded forested landscapes, but in grasslands that were meant to be fodder banks and soil binders in regions of sparse precipitation, they disrupt species behaviour and the very survival of birds such as Desert Coursers and Sandgrouse that are unable to find suitable and safe nesting sites. Mammals like blackbuck and chinkara suffer increased risk from ambush by their natural predators and, now, from feral dogs. Some grassland amphibians and reptiles that live/hibernate in burrows under the soil have been recorded losing vital habitats, even as they are targeted for massacre in large numbers.

A whole book could be written on power producers, that once used coal as their feedstock and who are unaware of or unconcerned with the adverse impact of their plans on arid grassland ecosystems. They have emerged as the last and possibly greatest threat to endangered species such as the Great Indian Bustard, Little Florican, and a panoply of eagles, flamingos, cranes and other large avians. These birds collide with, and are electrocuted by, haphazard mazes of powerlines set up to evacuate electricity from industrial scale solar power plants that are destroying grasslands in a quest for the so-called ‘green energy’.

A trio of Great Indian Bustards under a lone shrubby tree in the vast expanse of the Desert National Park, Rajasthan. Such scenes are rare today as GIB populations have plummeted. It is imperative we demarcate inviolate grasslands (preferred GIB habitat across India) if we wish to save this enigmatic species from extinction. Photo: Mainak Ray.

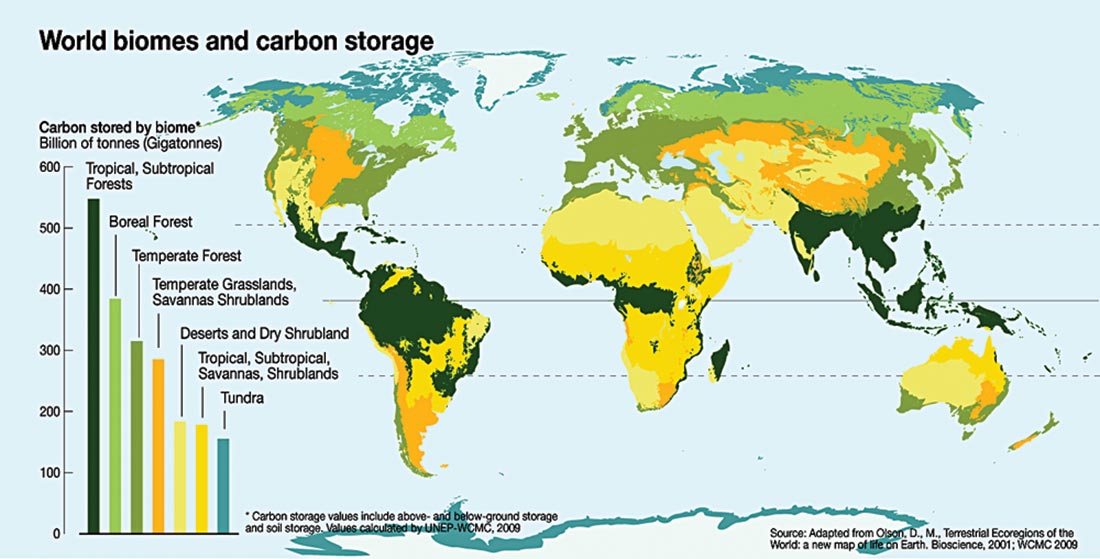

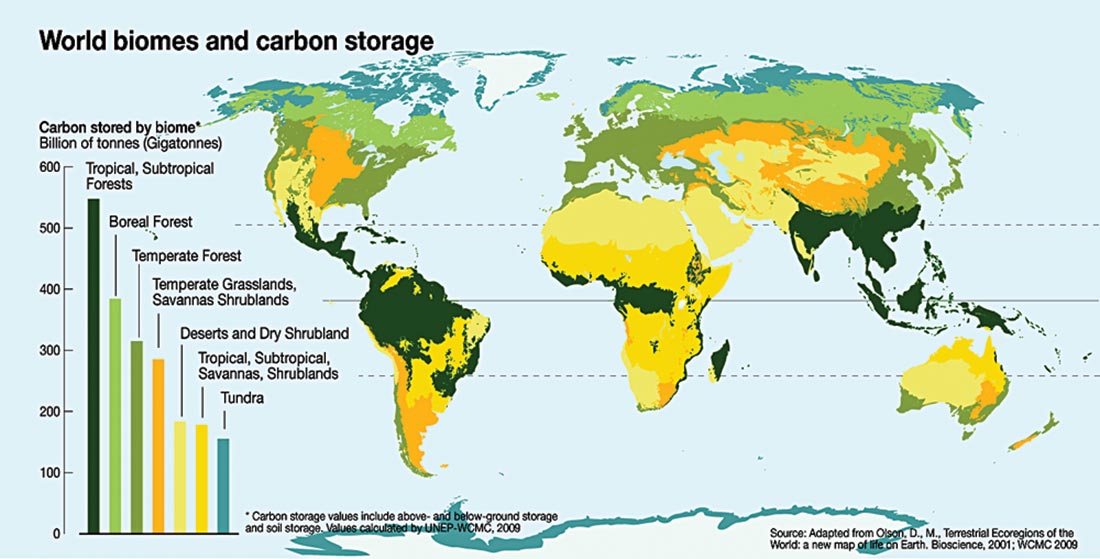

Photo: Public domain/GRID-Arendal.

Grasslands Against Climate Change

Photo: Public domain/GRID-Arendal.

Grasslands Against Climate Change

Grasslands account for 20 per cent of the global soil carbon stocks. Carbon is stored in the roots and soil underground in such ecosystems, unlike in forests, which have a higher above-ground storage of carbon. Grassland plant species have an extensive fibrous root system. This underground biomass extends far below the surface and stores abundant carbon into the soil, resulting in fertile soils with high organic matter content. As such, soil carbon accounts for about 81 per cent of the total ecosystem carbon in grasslands. Studies have shown that within certain eco-climatic zones, grasslands are more stable carbon sinks than equivalent forests.

The Grasslands Trust uses visual media including images and film to initiate discussions with villagers and the Forest Department to win protection for grasslands and the wild species that call grasslands home. Photo: Viraaj Apte.

The Way Forward

The Grasslands Trust is currently working in collaboration with the Forest Department and Animal Husbandry Department on some projects and training sessions about the biodiversity and importance of protection of the grassland ecosystem, and the need to curb further trenching and afforestation efforts in this habitat. Awareness sessions are also conducted for urban and peri-urban populations living in and around cities close to these grassland habitats. Such communities, because of their proximity, face problems of conflict with grassland predators. The Grasslands Trust works with residents, farmers and shepherds to introduce them to the biodiversity of their landscapes, generating a sense of pride and desire to protect the ecosystems and species they often revere, yet threaten. We help with speedy compensation for livestock losses at the hands of wild animals, provide solar lamps and sustainable livelihood alternatives suitable to their traditions to reduce or deter any retaliation towards wildlife.

We are also working on producing conservation films to engage wider audiences on the importance of grasslands. Our team has provided support for research projects for fitting GPS collars on animals to understand their movements in the Pune district to help formulate future conservation policies, in projects led by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE).

Photo: Aditya Singh.

The Cheetah Reintroduction Programme

Photo: Aditya Singh.

The Cheetah Reintroduction Programme

In an effort to reintroduce the cheetah (that went extinct in India in 1947) to India’s grasslands, a project is currently underway to translocate African cheetahs from Namibia to the certain Protected Areas across the country. Cheetahs are grassland specialists, and the project hopes to provide a flagship species to the habitat in order to aid its conservation. Some conservationists and environmentalists, however, point out that the project is flawed, as it depends on the Protected Area model for a species that is known to require hundreds, if not thousands, of square kilometres of habitat. The project will also require strong grassland policies in place to allow for more grassland habitat and therefore more space for cheetahs to procreate and expand. Read more about the project here.

Such bottom-up approaches are vital, but it will take nothing less than a national Centre-State policy initiative to recognise, identify, protect and restore grasslands as hardcore infrastructures. Currently, most such grasslands are categorised as ‘wastelands’ with open season declared on converting them to agriculture, urban development, and, tragically, ‘afforestation’ projects that end up with tax money being spent on doing more damage than good. A strong policy that confers grasslands the respect it deserves will prevent mismanagement. It will also help the livelihood of the residents of the landscape by generating sustainable fodder supply for their livestock and, if well managed, would also greatly supplement their income by attracting birders and other naturalists to enter their future-ready, regenerated world. I look forward to that day so that the wolf pack of Diveghat and the grassland wildlife of the Indian subcontinent become a primary source of livelihood and pride for the residents of grasslands, those little appreciated, yet vital ecosystems that hold one critical masterkey to the survival of life on Earth.

Mihir Godbole is a wildlife photographer-turned-conservationist who founded The Grasslands Trust in 2019 with his team. A charitable trust based in Pune, it works to conserve wildlife in open savanna habitats.

Dr. Abi Tamim Vanak is a Senior Fellow at ATREE and is an ecologist with broad interests in animal movement ecology, disease ecology, savanna ecosystems and wildlife in human-dominated systems.

Iravatee Majgaonkar is a researcher and is currently a Ph.D. student at ATREE, studying how savanna fragmentation impacts people-carnivore interactions.

Nikita Sabnis has an M.Sc. degree in Zoology from the University of Pune. She worked at IISER, Pune, for three years and now works with The Grasslands Trust.

_Velavadar_DSC_0313_SWPA-2020_C-1100_1654499628.jpg)