Shhh Can You Hear Me?

First published in Sanctuary Cub,

Vol. 45

No. 5,

May 2025

Each landscape has its collection of sounds, which mix biological, geological, and human sounds. The study of these ‘acoustic signatures’ helps us piece together the stories woven by creatures, nature, and humans. By Pavithra Sundar.

The Soundscape

The booming alarm calls of the langurs resonate through the dry forest in the buffer region of the Kanha National Park in the heart of India. A Red Junglefowl calls harshly as it scurries across the forest floor, while the sambar chips in with its loud warning calls. Meanwhile, the morning sun peeks through the Tamil Nadu’s Valparai hills, slowly nudging the rainforest awake and filling the air with the dawn chorus.

While the leaves dance to the rhythms of the wind, the Grey-headed Canary Flycatchers let out squeaky whistles as they flit from one branch to the next. Up north in Mumbai, the Purple-rumped Sunbird twitters as it flies for its morning bout of nectar, while the Coppersmith Barbet’s calls reverberate through the concrete jungle before getting drowned in the urban din. What do you think is common to all these places and yet so unique? The sounds!

The ‘soundscape’ is all the sounds coming from a landscape – from birdsong and burbles of a stream to the croaks of frogs and noise of traffic! Each landscape has its signature collection of sounds that contains a mix of biological, geological, and human-made sounds. The study of these ‘acoustic signatures’ is called ecoacoustics, through which we can piece together the unique stories that are woven by the creatures, natural elements, and humans.

A researcher listens intently for bird sounds in Kanha’s buffer forest. Photo: Pooja Choksi.

Listening In

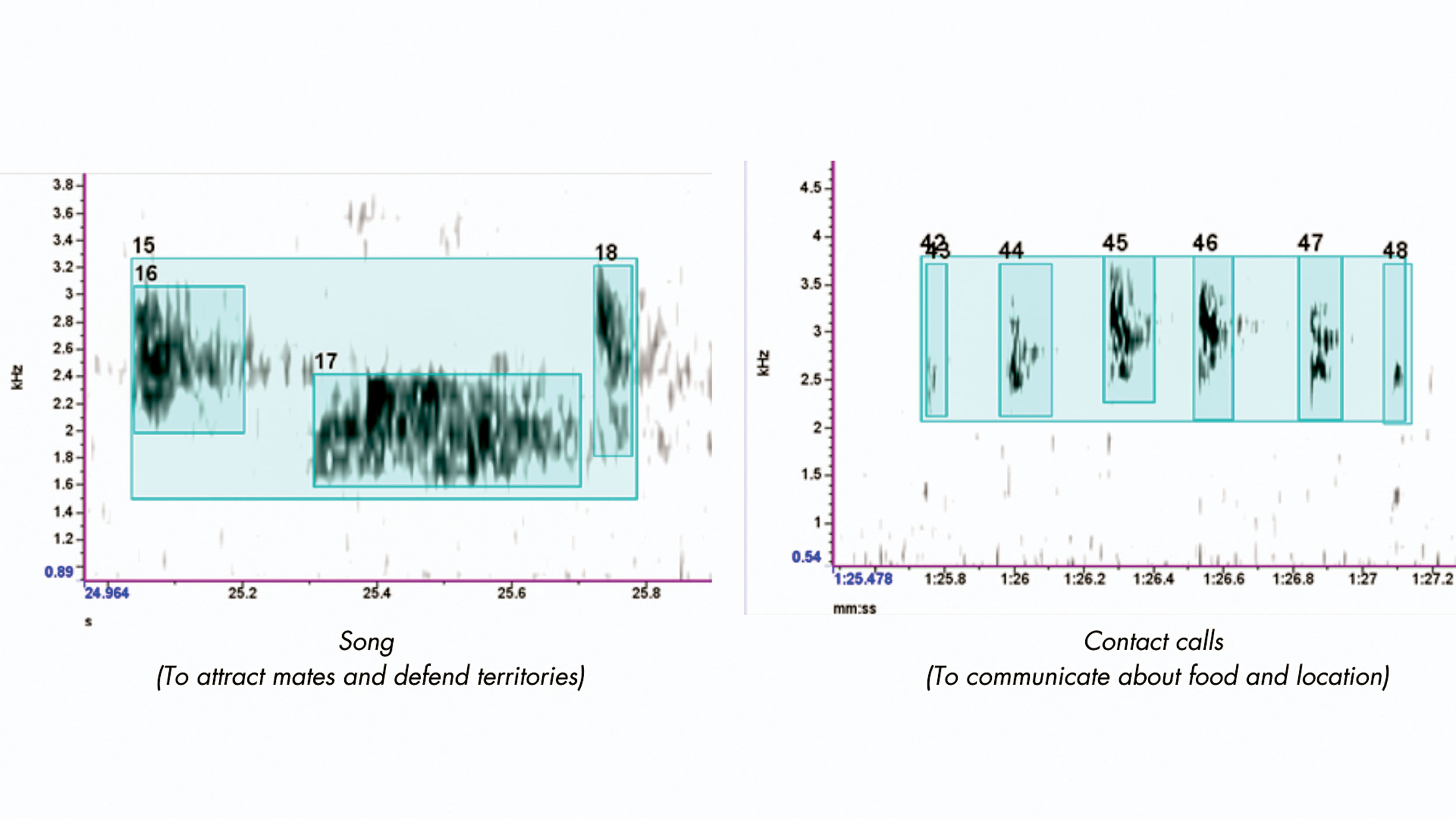

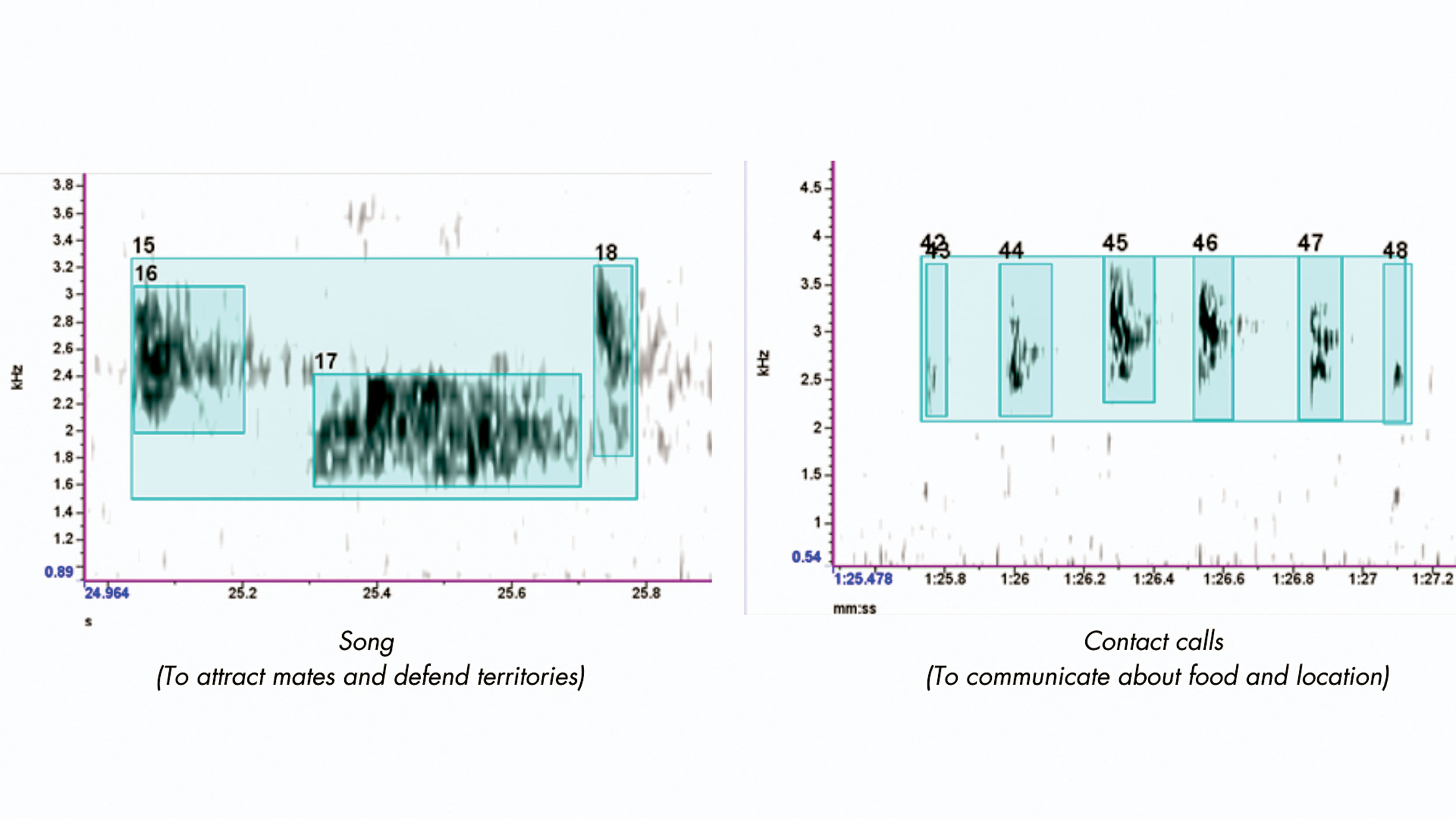

Just like you use your phone to record voice notes, we use recorders to capture the sounds of the forest. We then retrieve them to listen to and visualise the recorded soundscapes in the form of spectrograms. Spectrograms show the frequency, time, and loudness of a sound. The louder the sound, the brighter it lights up on the spectrogram. While analysing loads of data, it is always delightful to stumble upon recordings that showcase the forest in full-blown action – a tiger roaring to warn off intruders, the Racket-tailed Drongo slyly mimicking a Shikra, or the Common Hawk-Cuckoo vocalising to signal the start of peak summer.

A chorus of animals awakens the Valparai rainforest. Photo: Vijay Ramesh.

The central Indian forests, where we work, are home to the largest population of big cats, but the auditory dimensions of these forests cast the limelight on a host of other biodiversity, such as insects and birds. Eavesdropping on these forests tells us how these spaces are shared between people and wildlife – the birds chorusing at dawn, while the village on the fringes of the forest wakes up and goes about its chores. Using soundscapes, we could study how Red-vented Bulbuls that love Lantana camara, an invasive shrub that has been spreading across the landscape and preventing the local people from accessing the forest for livelihood purposes, respond to the removal of Lantana. Interestingly, we found that they tweak their vocalisations to make themselves heard in different vegetation types.

Audiomoth recorder to record all the sounds of the landscape. Photo: Public Domain/USFWS.

The spectrograms of Valparai’s rainforests, one of our other field sites, beam with the symphonies of endemics (found only in the Western Ghats) such as the White-bellied Blue Flycatcher and the Flame-throated Bulbul. While heavy downpours put a slow halt to the noisy cackles, pleasant mornings bustle with a medley of different species. Using acoustics, we recently found that birds vocalise more in the morning to advertise and defend their territories, and to communicate about food, especially insects.

The White-bellied Blue Flycatcher is endemic to the Western Ghats. Photo: Kandukuru Nagarjun/CC-BY-2.0.

Find Them!

~ Learning to identify species by sounds can seem daunting, but it only needs patient observation.

~ You can identify the birds you see or hear with Merlin Bird ID (https://merlin.allaboutbirds.org/).

~ eBird (https://ebird.org/home) has a section for bird sounds on each species page.

Animals vocalise to communicate about food, mates, and predators, vital for their survival. By studying these, we gain insights into why they do what they do, how they respond to their surroundings, and adapt to environmental changes. Recording and monitoring entire soundscapes helps track the health of forests over long periods. This is where acoustics emerges as a powerful tool. Although it has its limitations, harnessing its potential with technology can help us decode the mysteries of nature.

A spectrogram of Red-vented Bulbul songs, indicating frequency, time, and loudness. Photo: Pavithra Sundar.

The next time you find yourself amidst nature, tune into its music – you will be fascinated.

Pavithra Sundar, an aspiring ecological researcher, is an intern in the Great Indian Bustard Project of the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, and a research intern at Project Dhvani, which uses acoustics to monitor biodiversity.