Tiger Trackers

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 36

No. 4,

April 2016

By Raza Kazmi

“Tigers are usually found alone, but occasionally a pair will come out in the beat… Soon after the beat started I was amazed to see five large tigers walk out of the forest opposite me and begin to cross the river. They were a huge male tiger, an old female, and three two-year-old cubs. My shot killed the old female in the middle of the river, but the male had hung back in the fringe of the forest on the far bank, and at the shot he disappeared and was no more seen. One of the other guns dropped a cub in the river, but the others followed their sire to safety.”

This is what the famed forests of ‘Palamow’ were like during the days of the British Raj. Consequently it wasn’t much of a surprise then that the forests of Palamau’s (Palamu is the phonetically correct spelling that is also used) southern division were among the first of nine Project Tiger Reserves to be notified in 1973. After meticulous surveys were conducted, an area of 1,026 sq. km. comprising the Betla National Park and the Palamau Wildlife Sanctuary were set aside for the tiger and other denizens of these forests. A brilliant Field Director, the late J. P. Sinha, spearheaded the resurrection of Palamau, duly supported by the legendary, late S. P. Shahi, who was the Chief Wildlife Warden of Bihar at the time.

By the late ‘80s, Palamau was categorised among the best-managed tiger reserves of India and was a renowned wildlife destination. “Mohammad Rafi sahib visited Palamau a number of times, and he would sing for us too. He was slightly afraid of tigers though… I remember this one time he was drinking a bottle of soft drink in the canteen one evening. I was a young, mischievous assistant cook back then and with another canteen boy we started mimicking tiger grunts from the bushes. Rafi sahib ka cold drink chhoot gaya haath se aur wo hawa mein ucchal gaye darr se aur phir wo ekdum bhaag gaye room apna,” recalls Khairul miyan, the recently-retired khansaama (cook) of 40 years at Betla as he burst into laughter. “Wah… kya zamana tha! (What great times those were!),” he sighed with a twinkle in his eyes as we huddled around his warm chulha on a cold December night. Flipping through the yellowed, dog-eared pages of the visitor’s book that Hafizuddin miyan, the tracker-cum-librarian-cum-caretaker of the Nature Interpretation Centre at Betla, so proudly displays to all who ask to see it, I was granted a glimpse into another era: “It has been a brief but delightful stay. The sanctuary is one of the most well-maintained by national standards... I hope to come back here again someday,” reads the deep-blue lines inked by the legendary actor, Dilip Kumar. But the most precious and poignant comment was written in 1989. It reads: “…the boys on the firing line are doing a heroic job. The future of the tiger [in Palamau] is ensured.” The author was the late Kailash Sankhala, one of the greatest forest officers and conservationists India has ever produced. He was the driving force behind Project Tiger, and must be credited with putting Palamau on the national map by ensuring its inclusion among the original nine tiger reserves.

The Frontline Force

Most of those ‘boys on the firing line’ were daily wage labourers, known as ‘tiger trackers’ or simply ‘trackers’ in official parlance. Almost all of them joined the department as young lads in their late teens, either in the first few years preceding, or following the inception of the tiger reserve. By the late ‘80s, with erstwhile Bihar’s notorious malgovernance finally starting to take its toll, the tiger reserve’s management found itself unable to recruit new permanent staff (a problem still not solved, with current forest guard vacancies hovering around an unbelievable 97 per cent!). In this situation, the ‘tiger trackers’ became the frontline force defending Palamau’s wilderness. With the onset of Naxal insurgency in the park by the early 1990s, the task turned exceedingly dangerous. Long delays in funding led to the park losing ground and it tragically began to be written off by the larger conservation community. At this point the foot soldiers were unable to claim even their paltry monthly wages for months on end. Promises of being regularised into permanent staff, a hope they have carried ever since they first started working for the Forest Department, proved hollow. To top it all, Naxals began tightening their stranglehold over Palamau. But even in the face of such adversity, and virtual abandonment by both the state government and mainstream conservation organisations, the trackers, with their worn footwear, and tattered clothes, and a bag full of sattu (corn flour) and water, continued to patrol their turf, armed with little more than a pick-axe, a laathi, and pure grit. It is because they refused to give in that Palamau is still alive.

Their only support system comprised sympathetic and equally motivated officials between the early 1990s and 1998. Together, this motley crew of green warriors took on one and all, the deadly katha and timber mafias who were hand in glove with Naxal groups that would take a cut in lieu of the patronage they provided, local poaching syndicates, the illegal sand miners and the stone-mining mafia. Someone needs to wake up and thank these quiet foot soldiers for their service to the nation, against all odds.

The Truly Brave

The sacrifices made by Palamau’s tiger trackers were not just in sweat and hardship, it was in blood as well. On February 16, 1998, two trackers, Aziz Qureshi and Sukhdeo Parahiya, were martyred by a Naxal-laid landmine targeting the then Divisional Forest Officer’s (DFO) vehicle. There was an immediate change of guard at Palamau following this shocking tragedy and that one incident was enough to cause administrative screws to come loose. The first to abandon posts were senior managers and the mid-level staff. They completely withdrew from the Palamau Tiger Reserve, leaving it undefended against all enemies.

At this point, the daily wage workers, so ill-treated and under-appreciated, came to the fore. As the first and last line of defense for Palamau, the trackers remained true to their duty, and worked to the best of their abilities, saving what they could. Then in 2003, tragedy struck again when Tapeshwar Singh and Jitan Singh were slaughtered by Naxals who slit their throats. A year later, insurgents blew up a departmental truck, claiming that they mistook it for a police truck owing to the rented truck being painted in the police department’s dark blue hue. Daniel Khalko, a forester, and Sitaram Mahto, a tracker, died in this bloody attack. The same year, Bhagwati Yadav was bludgeoned to death by timber smugglers in Betla. Three years later in 2007, one of Palamau’s oldest trackers, Muhammad Umar or ‘Umar miyan’, fondly known as the ‘father of Palamau’s trackers’ was trampled to death by an elephant while on patrol in Betla. Baleshwar Singh, Ramji Oraon, Nanahu Yadav, Ramkisun Kisan, Vinay Singh, Atwariya Devi, Ganouri Ram, Nanhak Brijiya, Vishanu Mahto and Ramji Oraon are others who gave up their lives so that their beloved park could live on.

Naxalite attacks on forest rest houses, staff quarters, and wireless stations continued apace over a decade starting in 1998. Every once in a while a Naxal dasta would call up these trackers in one of their jan-adalats (peoples’ court) and publicly berate them, at other times they would thrash the unarmed trackers while attacking Forest Department infrastructure inside the park. The aim was to assert their ‘authority’ and to make their presence felt. To add injury to injury, all too often the same people would be thrashed by the security forces who falsely accused the nearest trackers they could lay their hands on, of being Naxal informers.

While this tragedy unfolded, wildlife conservationists across India were silent, as if to prove the veracity of Edmund Burke’s powerful observation: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing”. A few even went to the extent of labelling the entire tiger reserve a failure, loudly proclaiming that not a single tiger pugmark was to be found in Palamau, never mind that none of them had bothered visiting the park in decades.

Through all this, the tiger trackers of Palamau continued their forlorn battle, hoping against hope that their beloved tiger reserve would magically be resurrected one day.

Somaru Singh, a highly-skilled tiger tracker, climbs down from Kesra hills after a day’s work. Stuffed in his backpack are the camera traps installed by him and fellow trackers. These are being transported to the range headquarters. Photo Courtesy: Raza Kazmi

Chaturgun Oraon, among the best tiger trackers of Palamau, a member of a small tribal cult peculiar to some Oroan tribals from the central Palamau Tiger Reserve. The vermilion on the forehead and neck, long hair and the turban are distinguishing traits. Photo Courtesy: Raza Kazmi

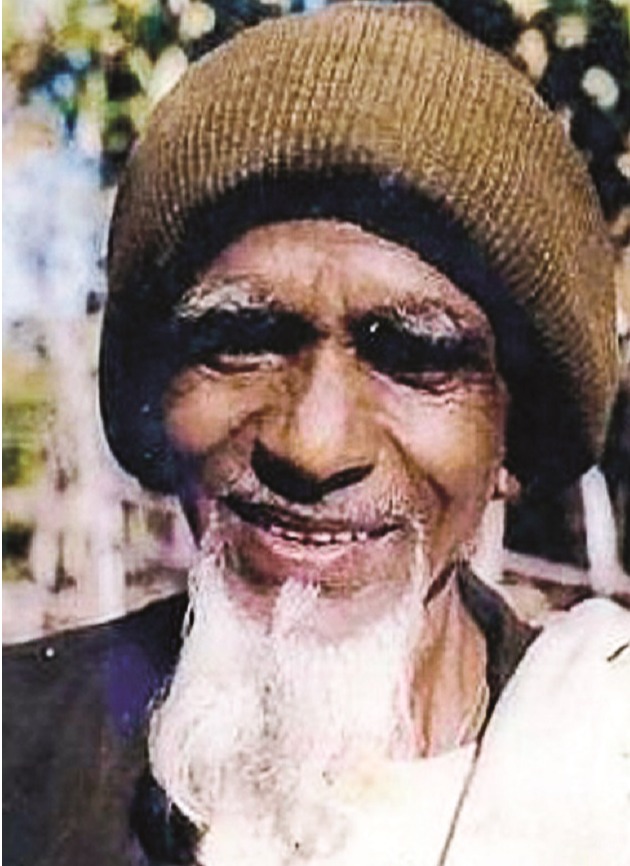

The ever-smiling late Umar miyan, is fondly referred to as the ‘father of Palamau’s trackers’ on account of his vast experience, length of service and legendary tracking skills. Photo Courtesy: Forest Department, Palamau Tiger Reserve

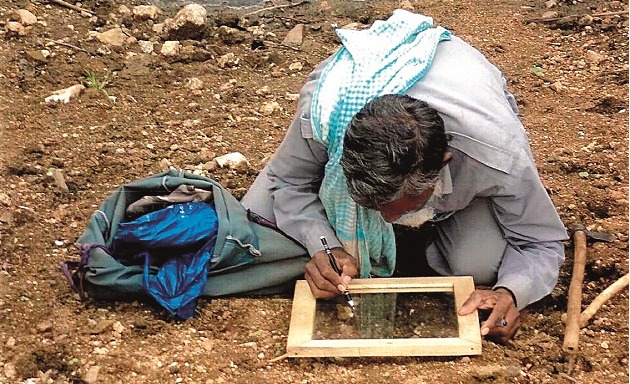

Umar miyan’s legacy lives on through his son Yasin miyan, who bears an uncanny resemblance to his father. An expert tracker, he now patrols the forests of the Betla range with his father’s tracking partner Salim miyan. Photo Courtesy: Forest Department, Palamau Tiger Reserve

The Rebirth of Palamau

About five years ago, the first signs of Palamau’s resurrection began to emerge. What it took was a few good men, placed in the right managerial positions. These individuals began to institute a modicum of administrative order to the beleaguered tiger reserve. Their efforts were rewarded by a marginal enhancement of Palamau’s physical area (from 1,026 sq. km. to 1,130 sq. km.). Men began to move back into areas that had been declared unsafe and out of bounds by previous administrative regimes. Abandoned staff quarters were refurbished, crumbling and destroyed rest houses resurrected, wireless towers rebuilt and forest beats and key forest ranges were reoccupied. Slowly, painstakingly, the Forest Department infrastructure was rebuilt and repaired. Monitoring and protection were beefed up. Incredibly, the first-ever preliminary camera-trap surveys in the Palamau Tiger Reserve were carried out on the orders of the Field Director, and it was the trackers yet again who implemented this welcome step, right from selecting sites for camera placement to retrieving and bringing images and equipment back to their respective ranges.

One of the boldest males in the tiger reserve snarls at a camera trap. Photo Courtesy: Forest Department, Palamau Tiger Reserve

The results astounded even the most optimistic officers. Tigers, mating leopard pairs and leopardesses with cubs, predators on kills (unfortunately mostly domestic cattle, underscoring the decimation of the natural prey base during the decades of strife), honey badger pairs sauntering about, and incredible images of small herds of nilgai that were thought to have gone extinct from the park decades ago. While much had undoubtedly been lost in a decade of debacles, enough had survived to encourage a renewal. Moreover, the exercise even resulted in the addition of a new mammal to Palamau’s fauna – the rusty spotted cat – the first-ever record of the species in the entire state!

The credit for all of this goes solely to the unrelenting efforts of the courageous, determined and dedicated tiger trackers of Palamau. It was their dogged refusal to surrender, while all others around them, including the State itself, abandoned Palamau that saved this tiger haven. It is time that these quiet, anonymous trackers are placed on a well-deserved pedestal.

Not that they want or expect any pedestal. The sheer look on their faces as they celebrated the first few tiger images to emerge from the camera traps laid out on the forest paths of Palamau in 2011 was reward enough for them.

I continue to meet these brave hearts who have survived more than 20 years of abandonment and aggression in equal measure. We justifiably celebrate the heroes who protect our borders, but while doing so perhaps it’s time to remember that it is the mud-on-boots defenders of wild India who protect our ‘desh ki dharti’ (the soil of our land), which is what provides our armed forces with the motivation they need to protect our borders. These unsung heroes truly sacrificed their all, including their youth and family-life – and their lives.

Today, many of the ‘boys’ Kailash Sankhala wrote about with love and admiration all those years ago have either passed away, or have metamorphosed into forgotten, old, grey-haired men. Many bear wounds on their bodies and spirits. Some of the grey-and-white-haired ‘boys’, amazingly, continue to hold fort, determined to watch over Palamau for as long as they can on salaries that seldom exceed Rs. 5,000 per month (U.S. $ 75). Not one of them ever got the ‘promised’ permanency of a post. Not even one got paid the dues owed to them for remaining on duty while others around him abandoned their posts.

That was then. Hopefully this article will trigger the conscience of the powers that be to right past wrongs. Surely there could be no better way to inspire the incredible new, young blood that has been infused into Palamau than by honouring the battle-hardened ‘old guard’ who must pass on the torch and prepare a new crop of trackers for future battles to safeguard this wild Eden in the most hostile conditions to be found anywhere in India.

Palamau, its people and its wildlife, continue to suffer in the cross-fire between the State and the various left wing extremists. Yet, having followed the fortunes of this park for close to two decades, I can say with confidence today to the late Kailash Sankhala that no matter how difficult the odds, your ‘boys’, both the ‘old oaks’ and their new protégés, will not allow the magnificent forests of Palamau, or its wild denizens, to vanish. They will do what it takes. They will continue to be the protectors of the Palamau inheritance gifted to us. They, and Palamau, will endure, come what may.

And we will tell our children tales of the never-to-be forgotten trackers on whose shoulders conservationists of all hues stand today.