The Wild Buffaloes Of Central India

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 8,

August 2025

By Raza Kazmi

What animals come to your mind when you think of charismatic mammals of the Central Indian forests? The usual answer would be tiger, leopard, dhole, hard-ground barasingha, and gaur. With the recent return of elephants to Central India, some would add these pachyderms to the list as well. But what about wild buffaloes? Most of us associate wild buffaloes Bubalus arnee with the fauna of Northeast India. Large buffalo herds roaming the grasslands of Kaziranga and Manas Tiger Reserves in Assam immediately roll into our imagination. However, few know that, historically, large tracts of the sal forests of peninsular India were also home to wild buffaloes, with these wild bovines once being an integral part of the faunal make up of this landscape.

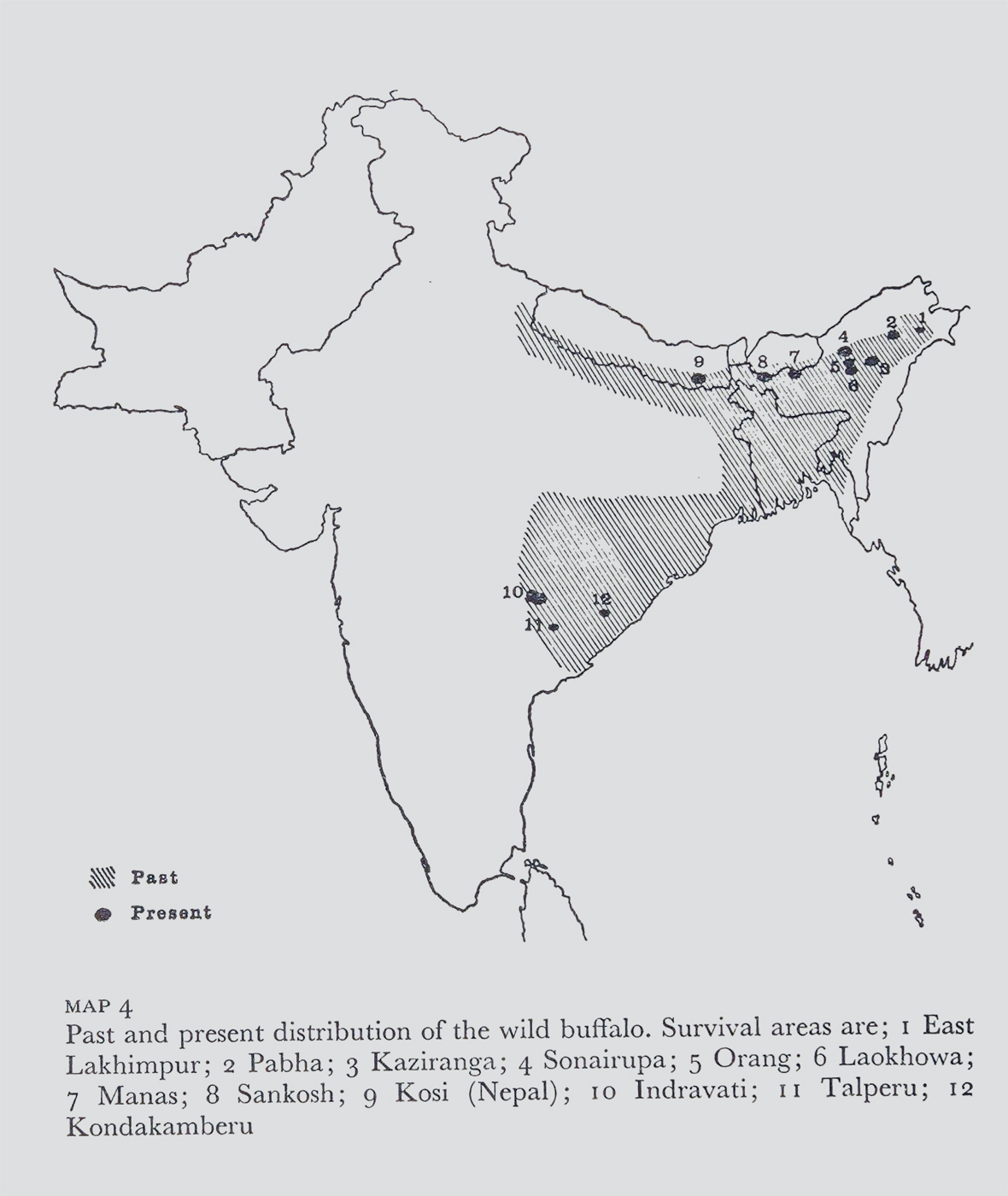

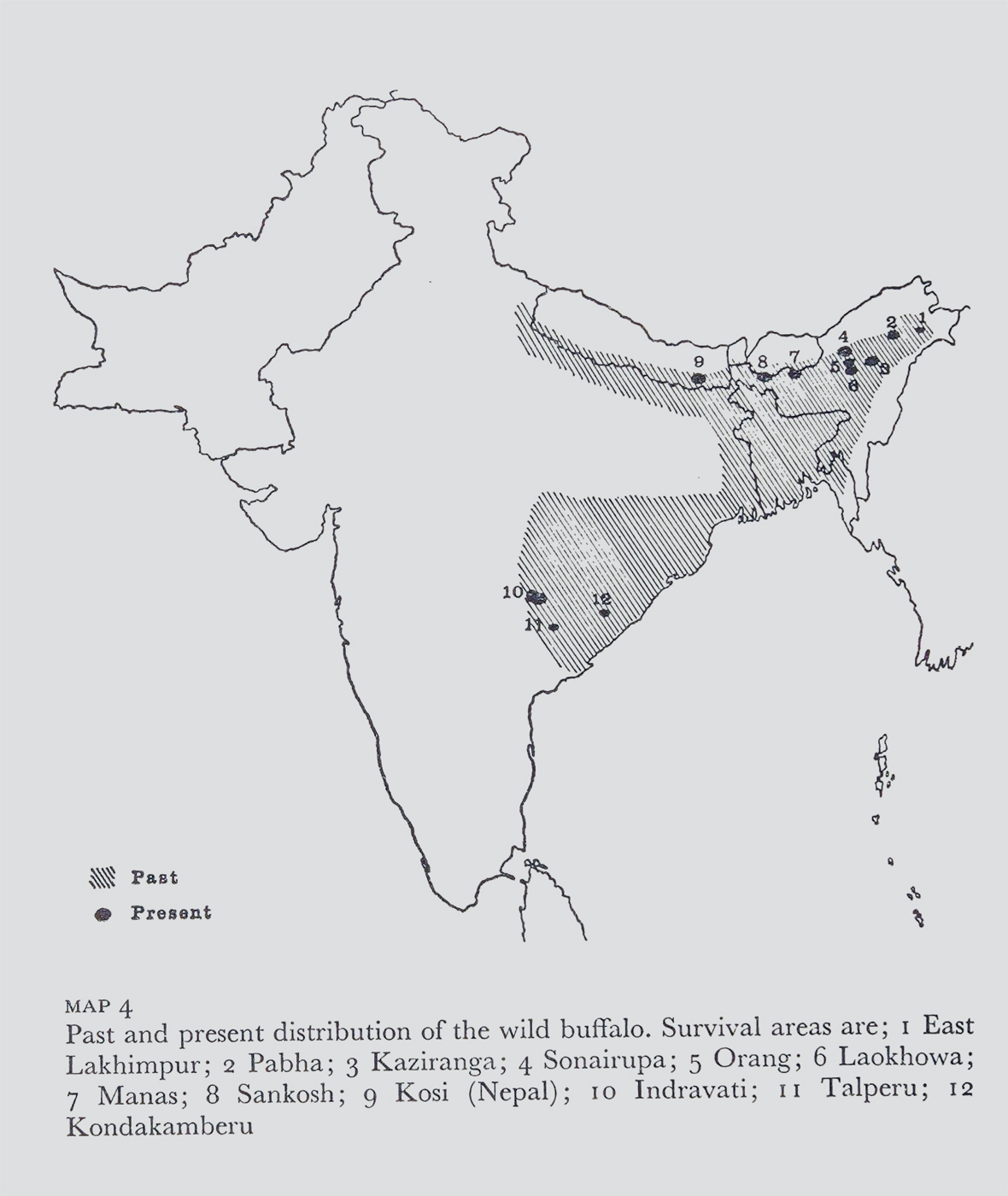

Once distributed across present day south-eastern Madhya Pradesh, north-eastern Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, northern Telangana, northern Andhra Pradesh, and parts of Jharkhand, these bovines were ubiquitous. Up until the closing years of the 19th century large herds, sometimes numbering as many as 100, were a common sight in the wilds of Central India, especially in what is now central Chhattisgarh. Here is what Captain James Forsyth witnessed while exploring the great forests of central Chhattisgarh in the 1860s:

"As we marched northward again we entered the valley of the Jonk river, a tributary of the Mahanadi, and here we fell in again with great herds of buffaloes… Around us was a sea of long grass, bounded by low hills and sal forests on the far horizon… When marching in the morning, about a couple of miles from camp we saw a herd of fifty or sixty buffaloes standing up to their knees in a swamp among long grass."

In fact, wild buffaloes of Central India carried a fearsome reputation among British hunters of yore owing to their propensity to charge aggressively when threatened, and being especially fierce when injured. Almost all shikaris of Central India described them as the most dangerous "trophy animal" in India.

But that was then.

The future of Central Indian wild buffaloes continues to hang by a thread as it remains largely overlooked in conservation initiatives. Photo: P.M. Lad.

A Rapid Decline

By the 1960s, the population of wild buffaloes in peninsular India had declined drastically, both in numbers and geographical range. The first ever scientific survey to ascertain their numbers in peninsular India was undertaken by a Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) team comprising J.C. Daniel, B.R. Grubh and George Schaller in 1965, wherein they estimated that the population of wild buffaloes had been whittled down to 400-500 across peninsular India. Their range had been confined to the then undivided Bastar district, home to about 250 to 300 animals with some seasonally crossing over from Bastar into eastern Chanda (now Gadchiroli), a few possible individuals in the upper reaches of Jonk valley, and a few in south Raipur forests (now the Udanti-Sitanadi Tiger Reserve). Another population, estimated to be about 100 strong, was believed to inhabit the Kondakamberu valley and Maheswarpur area (near Balimela) in southern Odisha’s Jeypore district (now Malkangiri and Koraput districts). Incidentally, they did not comment on their distribution elsewhere in Odisha, though other sources do hint at the existence of a few animals in Odisha’s Sunabeda plateau (lying east of the Udanti-Sitanadi Tiger Reserve) and Gandhamardhan hills as well. By 2000, another BNHS team led by noted conservationist and naturalist M.K. Ranjitsinh, who was the prime force behind bringing the last habitats of wild buffaloes in Central India under the Protected Area network through the creation of the Indravati National Park and three wildlife sanctuaries (Pamed, Bhairamgarh, and Udanti), confirmed the worst fears. Save for the Indravati National Park and the Udanti Wildlife Sanctuary, wild buffaloes had gone extinct from all their former habitats recorded in the 1965 survey, including the Pamed and Bhairamgarh Wildlife Sanctuaries that had been created specifically for the protection of wild buffaloes. This team estimated that the wild buffalo population of Bastar was now confined to Indravati, and had suffered a 90 per cent decline with barely 25-30 animals compared to the estimate of 250-300 animals for Bastar in 1965. The wild buffaloes of Odisha had already gone extinct by the 1970s, with the last stronghold of Kodakamberu valley and Maheswarpur in southern Odisha being submerged by the Balimela and Donkarayi dams. Ranjitsinh’s team sighted seven wild buffaloes in the Udanti Wildlife Sanctuary, and reported that the Forest Department’s estimate of 42 to 44 wild buffaloes for Udanti was, in all likelihood, a gross overestimate.

Today, the entire population of Central India's wild buffaloes is, by most estimates, even smaller than that of the single herd Forsyth saw in the Jonk Valley. The entire population now survives in a single landscape – Chhattisgarh’s Indravati Tiger Reserve (in the Bastar landscape) and the adjoining Kopela-Kolamarka forests across the border in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district. These forests have been severely afflicted by armed left wing insurgency for over 40 years.

Consequently, few outsiders can claim to have seen these shy bovines and it's difficult for anyone to arrive at reliable population estimates. Nonetheless, it is believed that there may be anywhere between 40 to 80 animals, divided into a few small herds that oscillate between the Indravati Tiger Reserve and the Kolamarka Wildlife Sanctuary. A relict, semi-wild population – consisting of a single captive female of disputed genetic origin along with a handful of heavily human imprinted males – completely cut off from the main Bastar cluster, inhabits the Udanti Wildlife Sanctuary in Chhattisgarh. They were part of an ambitious project to revive the population through in-situ breeding that, unfortunately, failed.

Estimated distribution range of wild buffaloes in India in 1969. Source: Twilight of India’s Wildlife (1969) by Balakrishna Seshadri. Borders neither verified, nor authenticated.

A Battle For Genetic Purity And Survival

But what makes the Central Indian wild buffaloes so special? Well, it is genetics, or genetic purity to be precise. Central Indian wild buffaloes are widely considered to have undergone little to no genetic dilution compared to their brethren in Assam. M.K. Ranjitsinh explains this in detail. He recounted that a significant number of domestic buffaloes and semi-wild stock (offspring of wild bulls that wandered into villages at the edge of Kaziranga) were abandoned inside Kaziranga in the 1970s, when the large cattle pens situated inside the national park were relocated out of the park boundaries. A few of these domestic and semi-wild buffaloes ended up interbreeding with the true wild buffaloes of Kaziranga resulting in the "genetic swamping" of the entire population. Ranjitsinh also recounted that "in Manas, the Bodo takeover of the park in the 1980s resulted in a drastic decimation of the wild buffalo and the invasion of domestic herds, the result being the same as in Kaziranga". Biologists widely believe that similar interactions between wild buffaloes and domestic buffaloes have occurred elsewhere across Assam and thus, affected the genetic purity of species not just in Manas and Kaziranga but across the state in varying degrees.

On the other hand, the central Indian populations were saved from this affliction, primarily because the female domestic buffaloes of mainland India are much smaller in size compared to those of Northeast India. Thus, while female buffaloes of Northeast India could occasionally carry a calf sired by a wild bull to term, the mainland female buffaloes were virtually incapable of doing so on account of the sheer size of such a foetus. The domestic female usually either died while birthing the calf or the offspring would be stillborn. If by some stroke of luck an offspring was born, the villagers found it to be very unruly to control if it was a male and with very little milk production capability if female. Consequently, the adivasis of Bastar were extremely averse to any male wild buffalo hovering around their villages. To add to that, the degree of interaction between wild and domestic buffaloes in Central India was far less than in the floodplain forests of Assam because, quite simply, there were fewer domestic buffaloes in the hinterlands of Bastar and Udanti.

A herd of Central Indian wild buffaloes sketched by Captain A.I.R. Glasfurd, from his book Leaves from an Indian Jungle published in 1903. Photo: Public domain/Captain A.I.R. Glasfurd.

The Struggle Continues

Despite the uniqueness of the Central Indian wild buffalo, and despite the 'Van Bhainsa' (literally translating to 'forest buffalo') being the state animal of Chhattisgarh, their conservation has received scant attention. Even as the ambitious project to revive their numbers in Udanti failed, no concrete conservation interventions were instituted for the buffaloes of Indravati at any point of time, owing to their inaccessibility and security concerns on account of Maoist activities. Consequently, instead of focusing on the extant population in Indravati, attention was shifted on relocating animals from the north-eastern population to Central India. Half a dozen wild buffaloes from Assam's Manas Tiger Reserve have been translocated for breeding purposes over the past five years to Chhattisgarh's Barnawapara Wildlife Sanctuary – a sliver of the once expansive Jonk Valley where Forsyth saw hundreds in the 1860s. As expected, serious concerns have been raised about this move because of the lack of understanding of the genetic differences between the Manas population and the Indravati-Kolamarka population, and also the complete lack of interest in preservation of the extant population in Indravati. Recent reports also suggest that the Madhya Pradesh Forest Department is considering bringing in wild buffaloes from Assam, rather than Indravati or Kolamarka, to re-establish them into their historic habitats in Kanha Tiger Reserve.

Thankfully, unlike Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra seems to have taken note of its buffaloes in Gadchiroli. After Atul Deokar, the then dynamic Range Forest Officer posted in Gadchiroli almost single-handedly brought attention to the existence of a few buffaloes in the Kolamarka forests, the area was declared a conservation reserve in 2013. A decade later, in 2022, the 181 sq. km. conservation reserve was upgraded to the status of a wildlife sanctuary. Today, the population of buffaloes in Kolamarka has increased from Deokar's first report of 10 animals to between20 or 25 individuals. Moreover, rather than look towards Assam, a recent proposal floated by the state aims to focus on captive breeding of Central Indian buffaloes by capturing some individuals from the Kolamarka Wildlife Sanctuary.

It would be an understatement that the future of Central Indian wild buffaloes continues to hang by a thread. Will they rise again, or will the last of them wither away, uncared for, and unmourned? Time alone will tell.

Writer and wildlife historian, Raza Kazmi is a Conservation Communicator with the Wildlife Conservation Trust, Mumbai. His field of expertise includes the wildlife history of India, conservation policy and issues unfolding in India’s ‘Red Corridor’ landscape.