The Sanctuary Papers - August 2023

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 8,

August 2023

Text by Shatakshi Gawade

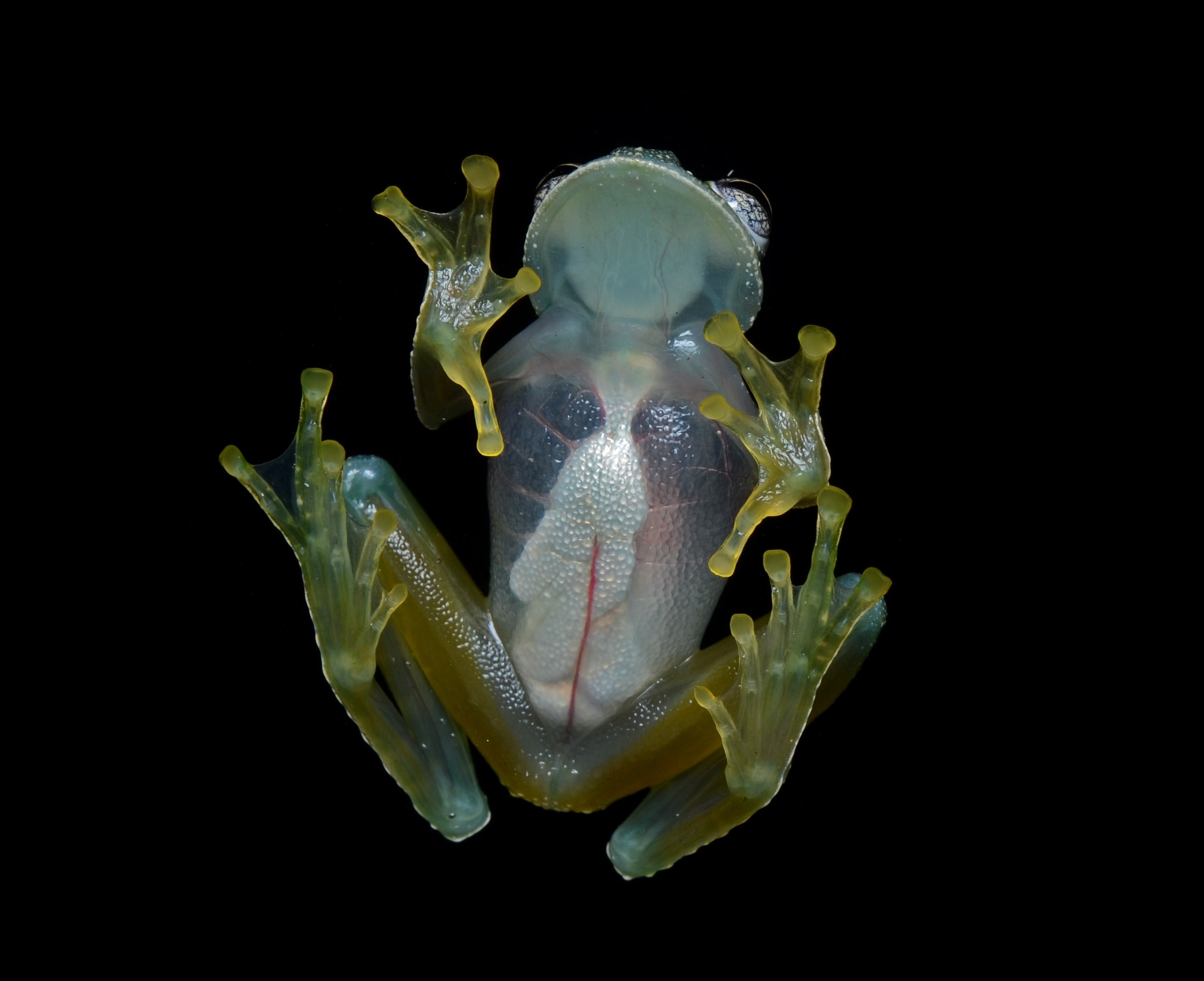

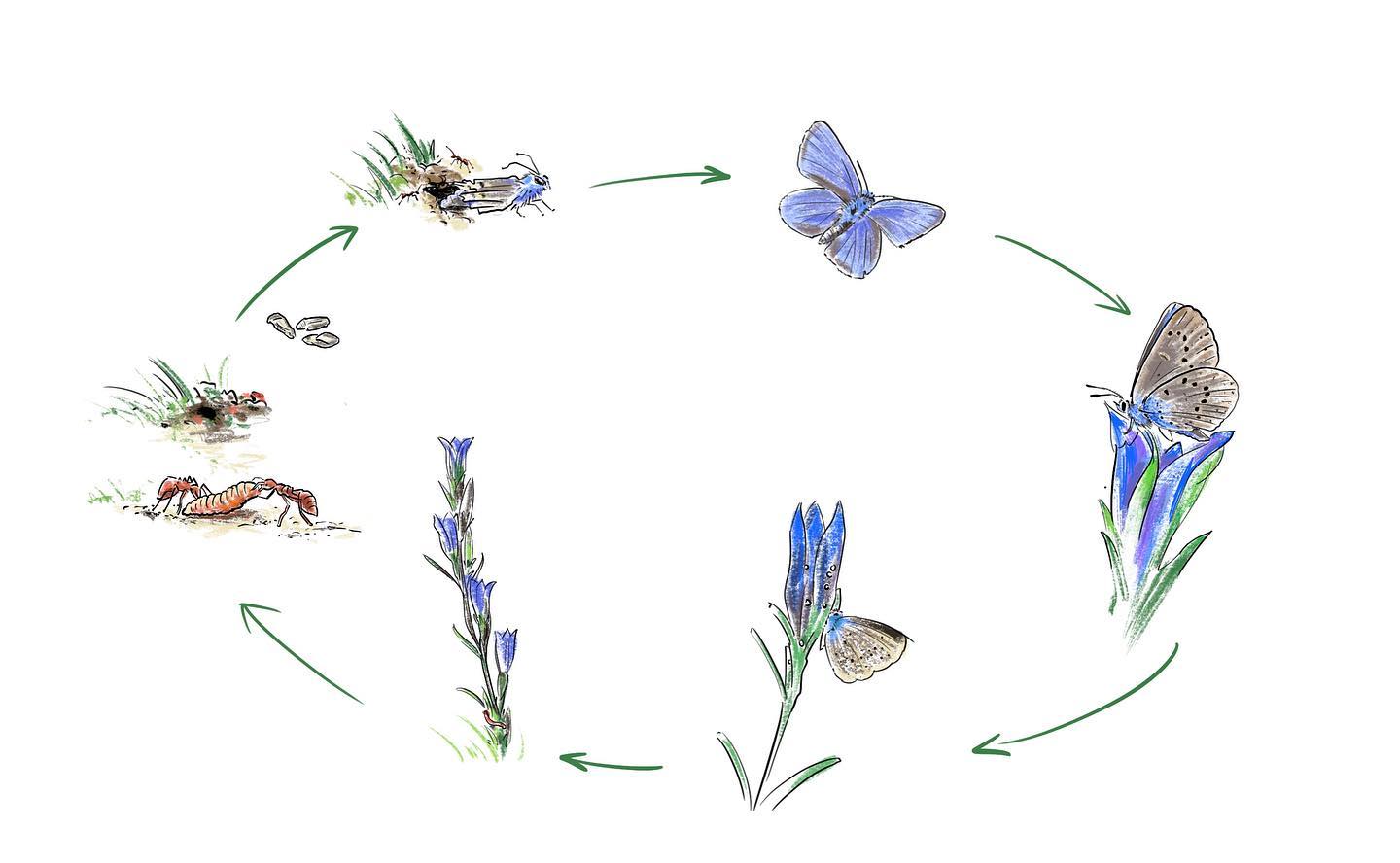

Now You See Me, Now You Don’t

Hidden in the tropics of Central and South America, the translucent glass frog is a fascinating amphibian. When a predator looks in its direction, it sees through the frog’s stomach! Since the glass frog is the most vulnerable when it sleeps, it becomes two to three times more transparent for about 12 hours by gathering about 90 per cent of its blood cells into its pea-sized liver. Like a well-thought-out costume, its liver is covered with minute reflective crystals to hide the red blood. The only problem with this 'invisibility cloak' is that it leaves the seven-centimetre wonder slightly groggy and stiff-jointed when it wakes up at night. Uncirculated blood after all means that the rest of the frog’s body is in an oxygen-starved state. An unlucky glass frog that is spotted just as it comes out of its transparent sleep could well become a snack!

Photo: Public Domain/FLICKR.

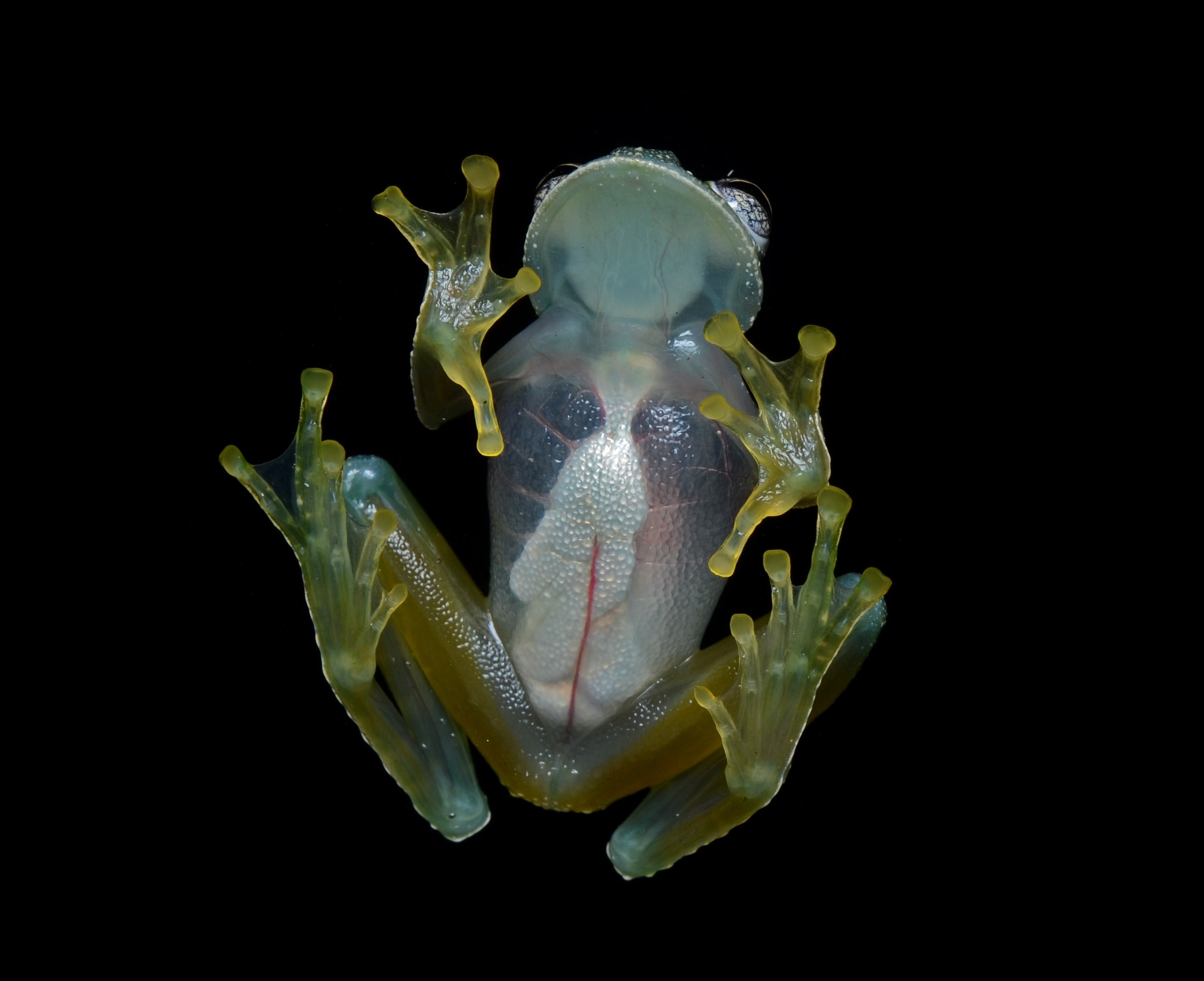

The Ungulates’ Magnificent Migrations

Every year, post the rains, over 1.5 million wildebeest also called gnus, make their long hazardous annual journey from the Serengeti across to Kenya and Tanzania. Gushing waters carry away calves, crocodiles lie in wait for stragglers, yet the migration is worth every hurdle. It leads them to water and fresh grazing. Other migrating ungulates (mammals with hooves) include Mongolian gazelles in Asia, caribou in the Arctic, and guanacos in South America. Migration is a critical strategy for animals to escape harsh climatic conditions, find sustenance and suitable breeding grounds. Travelling in large congregations has the advantage of enhanced security. Herbivores are an important link in the food web. They depend on vegetative matter and serve as prey for carnivores. Their trampling hooves and bodily wastes help form biotic communities so essential for healthy ecosystems. For millennia, humans have depended on such migrations to survive in otherwise hostile circumstances. The cultures of several traditional communities are still tied to the migration of species across the world. Today, however, ungulate migrations are threatened by anthropogenic hurdles. Large mammals need continuous, uninterrupted tracts of land. But when we plan linear infrastructures such as roads, fences, transmission lines and canals, we rarely if ever consider the impact on the disruptions we cause. These hurdles have become so severe that Planet Earth could well lose the ecosystem-defining migrations, even before we have fully understood them. The cascading effect of lost migrations will affect not just the animal kingdom, but the human world too.

Photo: Public Domain/RAWPIXEL.

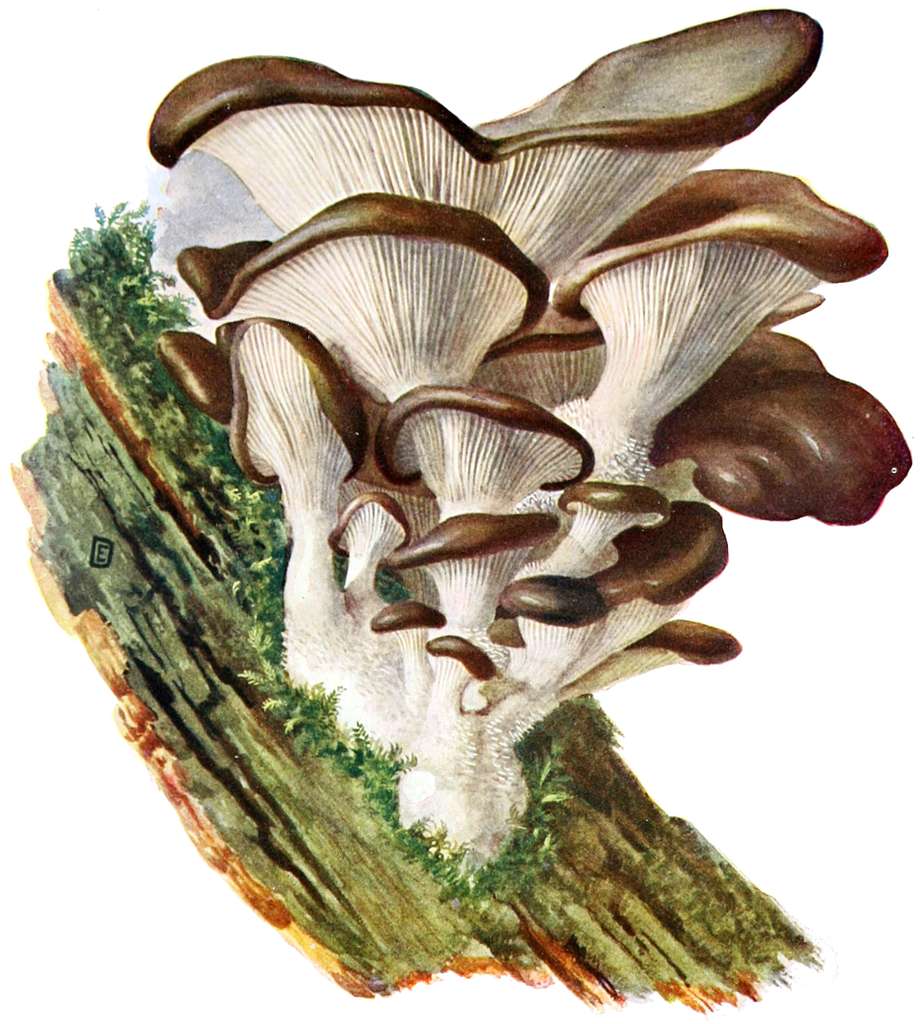

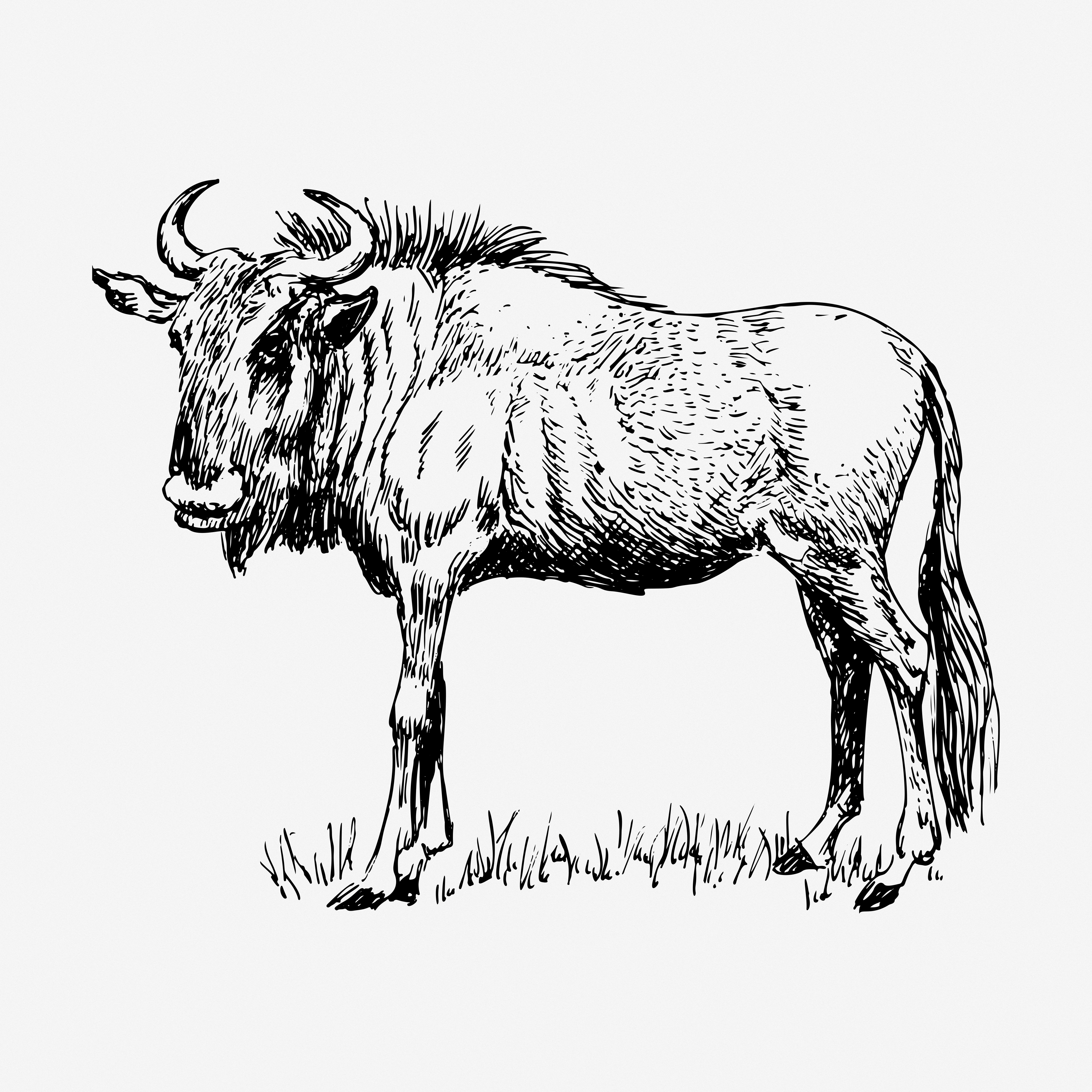

How Cool Are These Mushrooms?

What can be a natural replacement for ice cubes? Mushrooms! Scientists have found that mushrooms, as well as other fungi such as yeast and molds, have body temperatures that are lower than their surroundings. The oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus is close to 6°C cooler, and the brown American star-footed amanita is about 1°C or 2°C cooler. Mushrooms contain a high percentage of water, which they release to cool down, something like humans do by sweating. The gill structures below mushroom caps increase the surface area, allowing for greater cooling. Even fungi that live in colonies, such as yeasts and molds, have lower temperatures, more so at the centre of the colony. This condition persists even in freezing climates. An example is Brewer’s yeast, used to make penicillin. Single-celled fungi hold this characteristic, showing that cooling is a multi-species phenomenon among fungi. This may help spread spores, for reproduction, but could also be an inherent trait. When the scientists who found that mushrooms are inherently cooler made this discovery, they packed half a kilo of button mushrooms in a styrofoam box, and installed a fan to blow air from this box into a larger styrofoam box. The temperature of this makeshift cooler dropped by 10°C in 40 minutes, and remained so for half an hour! After such a box is used, you can simply eat the coolant (mushrooms) too, provided you ensure they are not poisonous!

Photo: Public Domain.

Did You Know?

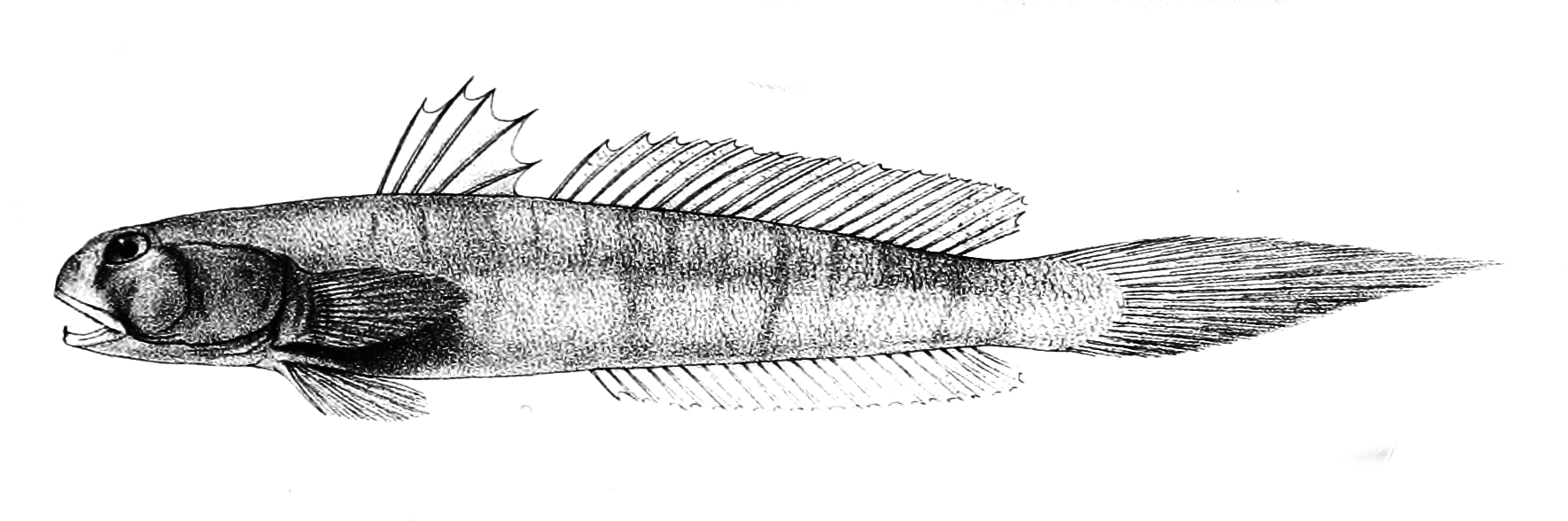

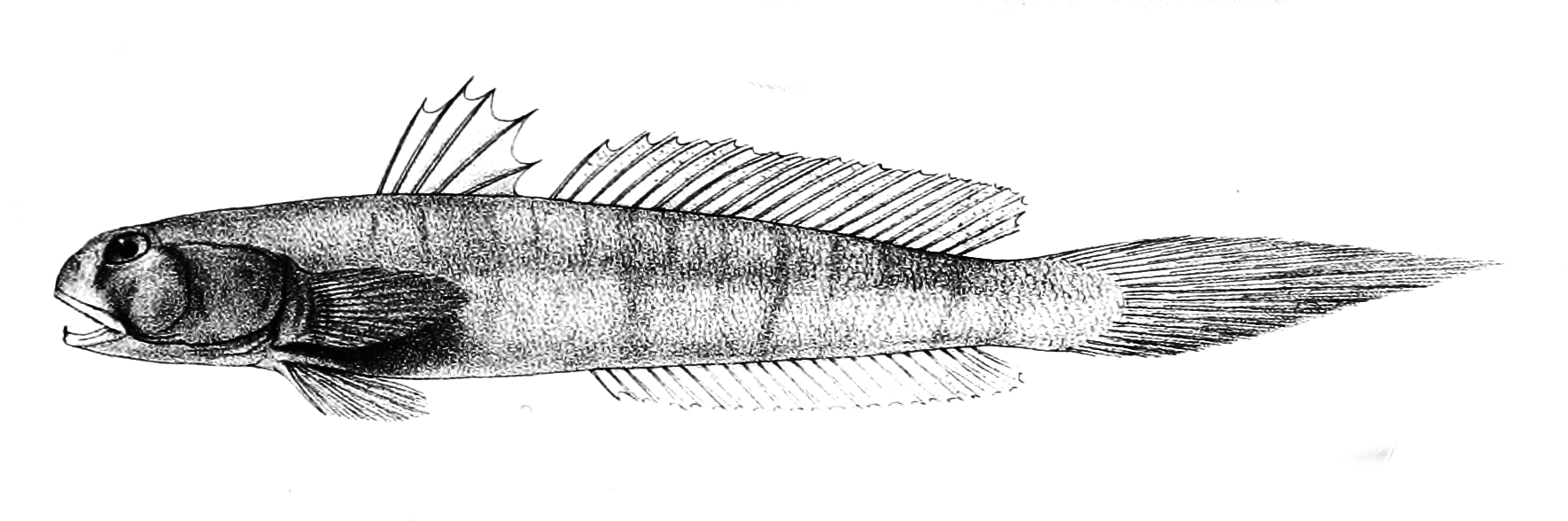

Floating nonchalantly at 8,336 m. below the surface of the sea, a tiny snailfish juvenile holds the record for the deepest video record of a fish. At this depth, the pressure is a crushing 800 times over that experienced at sea level… over 821 kg. per square centimetre! The hitherto unknown snailfish of genus Pseudoliparis, was recorded south of Japan in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench, home to a rich population of deep sea life.

Soaring in the Shadow of Volcanoes

Gliding smoothly on the wind, with occasional flaps and a quick twist of the tail for direction, the massive 15-kg. Andean Condor Vultur gryphus soars amidst the Andes Mountains in South America. At 3.3 m., it has the longest wingspan among raptors, which helps it to fly to the astounding height of 5.5 km. As the huge raptors have lived around humans for several centuries, they play a role in culture too – Andean Condors are revered by Indigenous South American communities. They are the national birds of not one but multiple South American countries, including Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador.

The history of this scavenger emerged from a very strange source – 2,200-year-old poop! Scientists found this ancient donut-shaped pile on a cliffside in Argentina’s Nahuel Huapi National Park, only to realise that it was a condor nest that had been used over millennia. Like many raptors, Andean Condors use the same site for extended periods of time. Analysis revealed that the accumulation of poop in the nest had thinned between 300 C.E. and 1300 C.E. On investigation scientists discovered that four volcanic eruptions had occurred near Nahuel Huapi around 300 C.E. The repeated use of nests warrants careful protection of these vital sites. Scientists also found that the faeces of current Andean Condors have more toxic mercury and lead than the older samples, and their populations are declining.

Photo: Public Domain/RAWPIXEL.

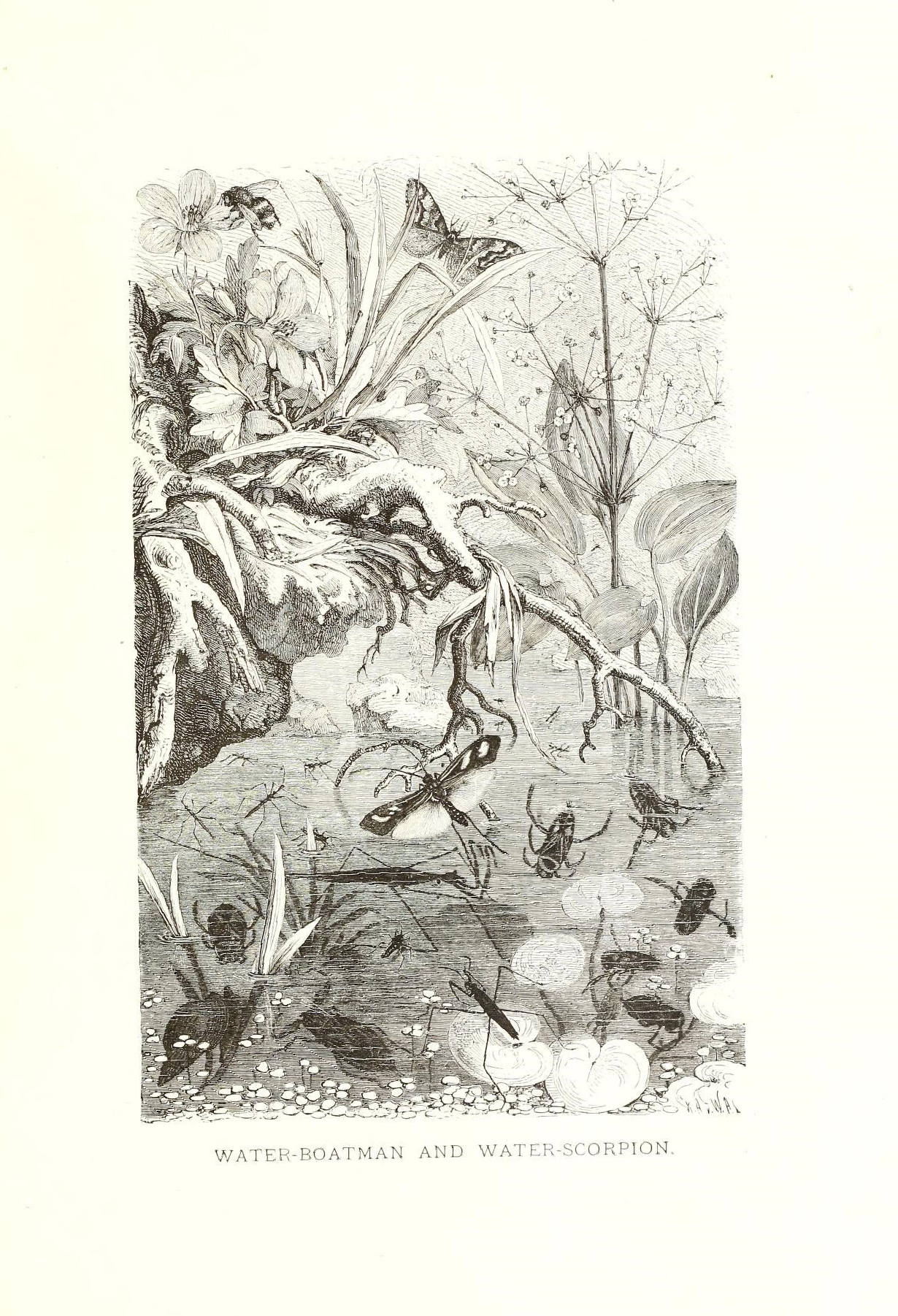

Still Waters Run Deep, and Noisy

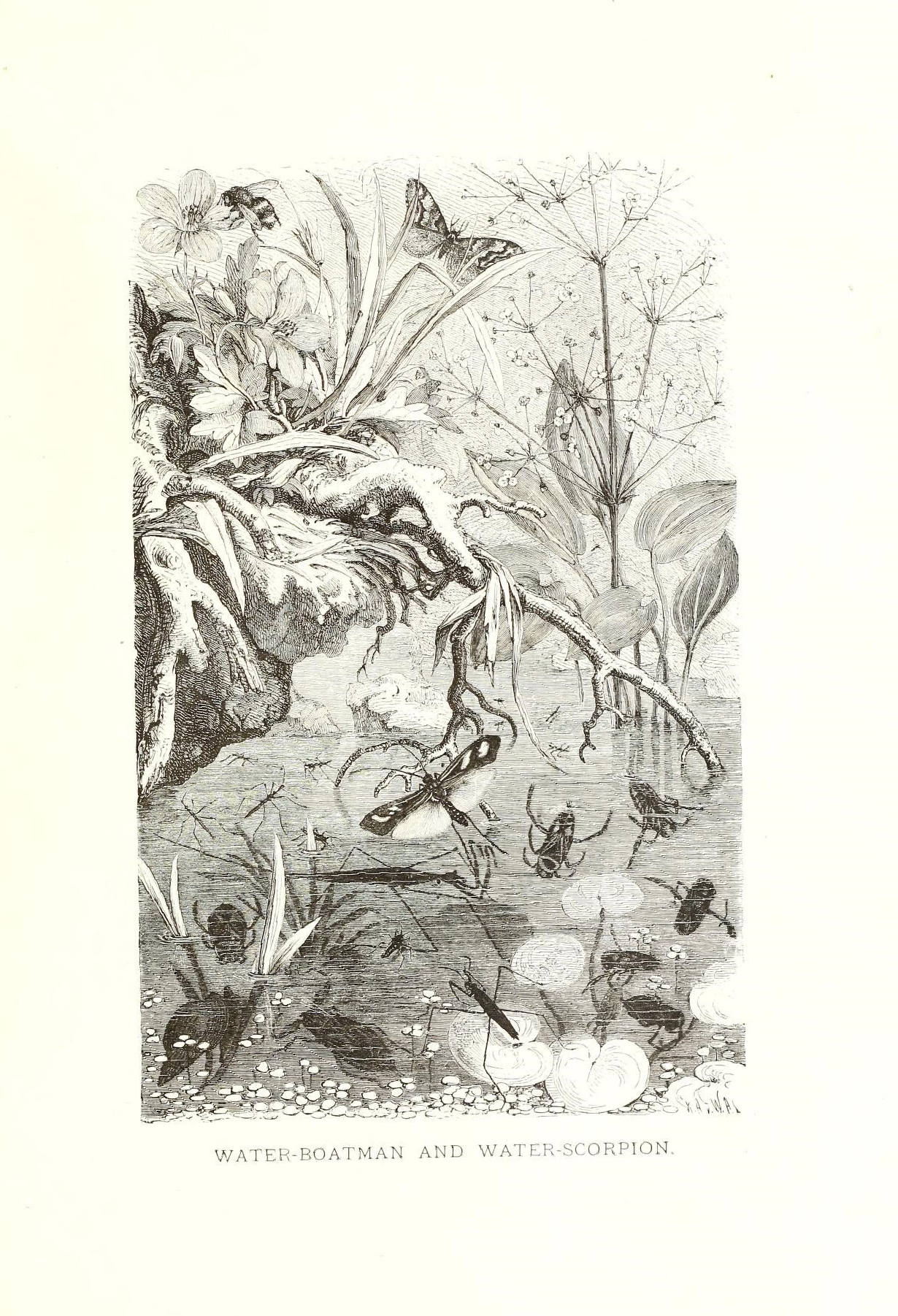

What sounds do you hear near a pond? The croak of frogs, some insects buzzing around, the beating wings of birds landing on the water, or rustle of the leaves as a gentle breeze flows by. But now, researchers have found that the still surface of the lake hides an entire orchestra underneath.

Under the still surface of a pond, different forms of life play operas and sonatas with strange and mysterious sounds – popping plants, scratching aquatic insects, and booming fish! Ponds provide important ecosystem services, and are extremely biodiverse microcosms of life.

During the day, plants dominate the underwater soundscape with buzzes, whines and ticks, all different breathing sounds as they respire during photosynthesis. At night, the insects take over the orchestra. As they compete to attract mates, some rub their genitals on their abdomens (stridulations), to make loud scratching noises. The pygmy water boatman, for instance, can produce the loudest sound while stridulating (when scaled to its body length) at 105 decibels!

The underwater sounds of ponds help assess the health of the ecosystem. The sounds can also be used to identify different species without capturing and possibly harming them.

Photo: Public Domain/Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Did You Know?

A 9,550-year-old Norway spruce on Fulufjället Mountain in Sweden is one of the oldest living trees on the planet! Old Tjikko appears to be a stunted shrub just 1.8 m. in height. It managed to survive through vegetative propagation, wherein a new plant grows from the parent’s parts. Carbon dating revealed the age of its root system. Think about it! The tree must have sprouted in 7550 B.C.E., whereas writing was first invented around 4000 B.C.E.

In the Eye of the Beholder

Bringing to mind the first organisms that ventured out of the primordial soup, the mudskipper pulls itself out of a squishy hole in the mud, venturing onto land with what looks like determination in its protruding eyes. Mudskippers are fish that spend most of their life on land, breathing air through their skin, and by trapping air in gill chambers.

The fish are found in estuaries, swamps and mud flats from Africa to Polynesia and as far as Australia. As tides retreat, they leave their watery abode in search of mates and food that includes a host of tiny animals and plants found on mudflats and make for squelchingly delicious meals for these amphibious creatures. To survive, however, mudskippers must ensure they remain moist at all times, which accounts for them flopping from side to side in wet mud.

Scientists have recorded 23 species of these amphibious fish, all belonging to the goby family. All ray-finned fish, they use their pectoral fins to drag themselves forward while on land. Scientists recently discovered that mudskippers blink by sucking their eyes down into their sockets using an existing set of muscles. The finding revealed that the evolution of complex behaviour in animals does not necessarily need physical changes, such as new glands and muscles, if the objective can be accomplished using existing anatomy. By comparing fossils of early tetrapods (four-limbed animals) with mudskippers, scientists surmised that blinking emerged as an adaptation to life on land for both groups and helps to perform three complex functions simultaneously – protection, cleaning, and maintaining wetness.

Photo: Public Domain/Wikipedia.

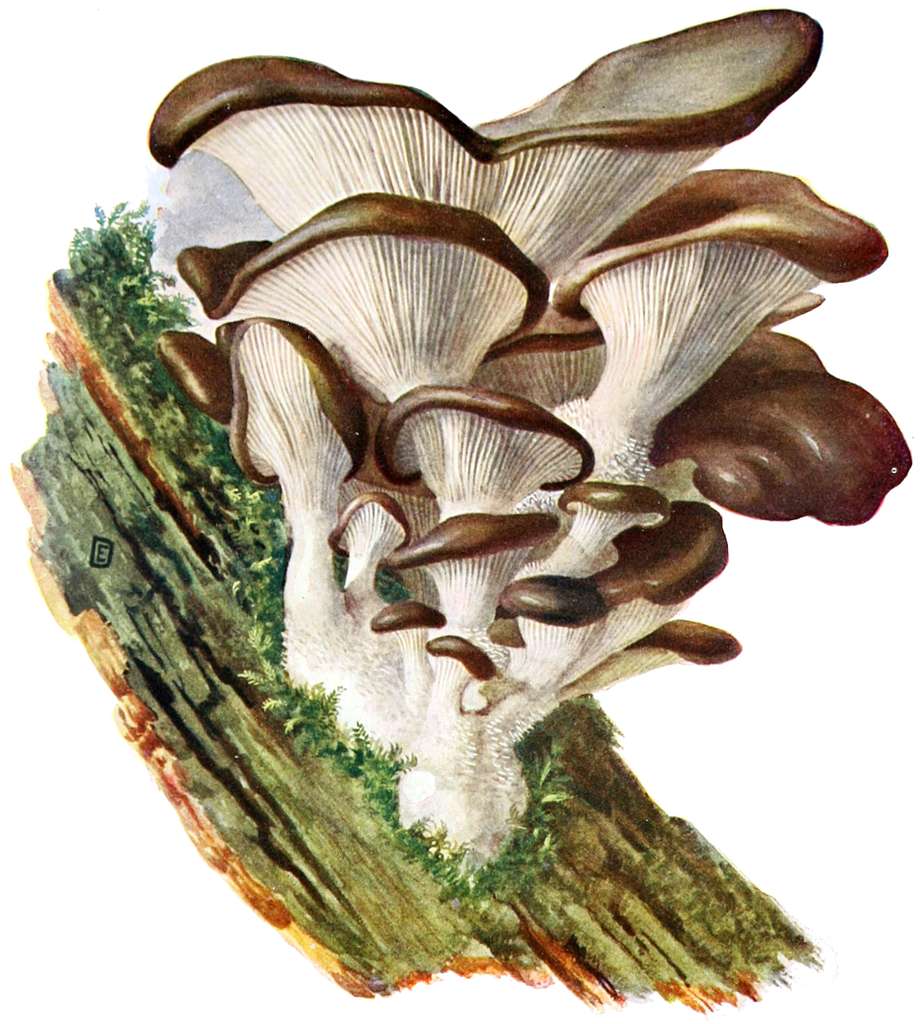

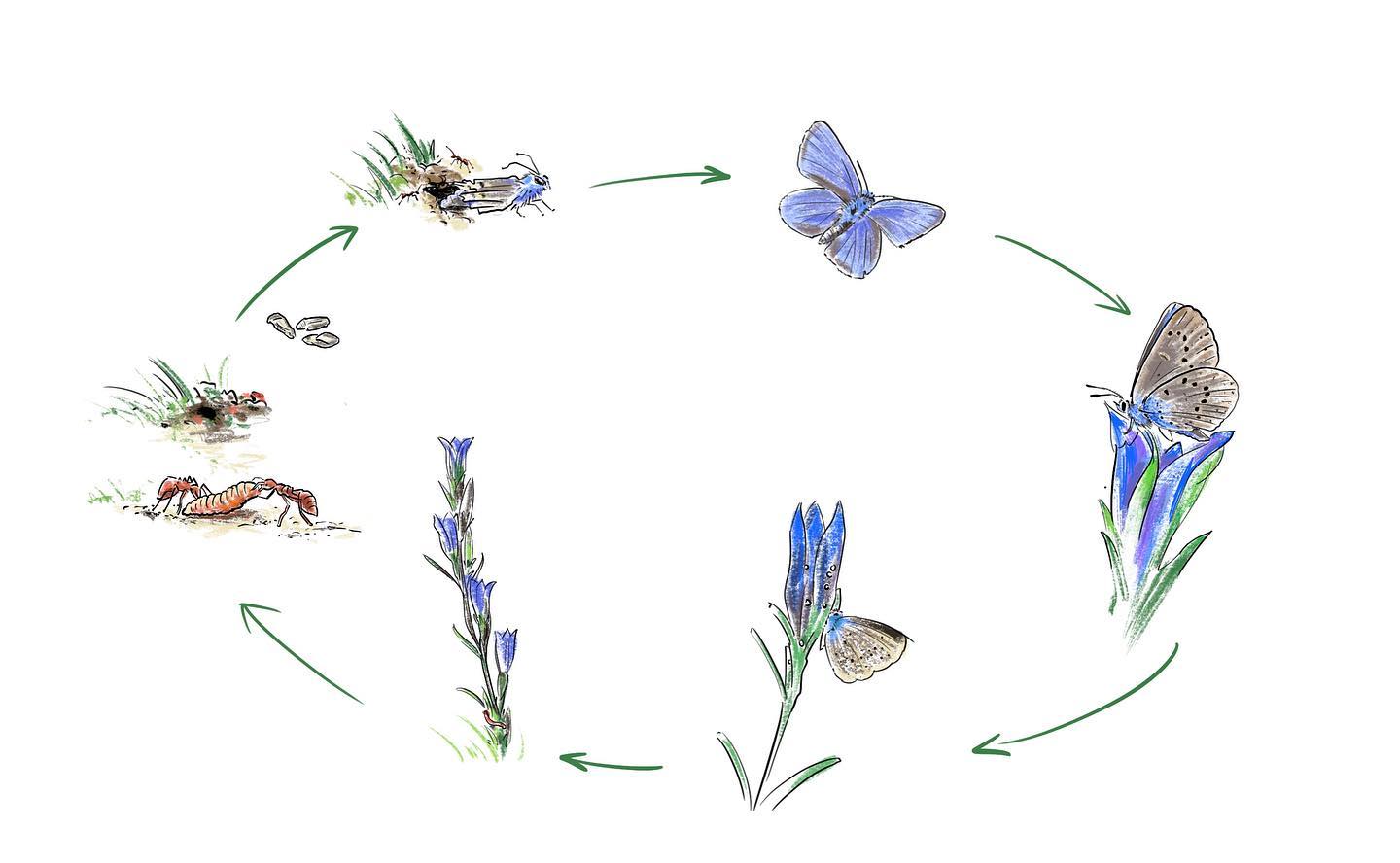

A Sentinel for the Heath

Standing innocuously in the middle of the forest floor or a grassland, sometimes almost blending into the surroundings, ant mounds are an integral part of the ecosystem. Worker ants build the mound for their colony by excavating the ground. The dug-up soil gets deposited above ground and can take the shape of towers, craters, or miniature hills depending on the species.

In the Danish heathlands (a type of shrubland habitat), ant mounds warm up the surrounding ground, which beetles, snakes and lizards use for warmth. When ants, such as the rare narrow-headed ant Formica exsecta and yellow meadow ant Lasius flavus, form mounds, they carry dead animals into their abode, which release heat when they decay, and add carbon and other nutrients to the heathland soil. In a regenerating forest, the seeds of many plants depend on such mounds. A plant growing on a mound is likely to flower earlier than other plants and the extra flowering period helps other insects! The Alcon blue butterfly makes particularly good use of ant mounds. When the caterpillar is sufficiently developed, it emits a scent and a sound that mimics the queen ant larva. This tricks worker ants into nurturing it, even at the expense of their own colony! In spring, the butterfly spreads its gorgeous blue wings and leaves the ant mound. Eleven of the 12 gossamer-winged butterfly species of Denmark thrive in places that have ant mounds.

Photo: Public Domain.

Did You Know?

The domestic cat’s nose functions as an extremely efficient gas chromatograph, a tool that separates and detects chemicals in vapour form. The complicated collection of tight, coiled bony airway structures in its nose help the cat quickly detect friend, foe or food. The cat’s nose separates the air it breathes into two streams, one of which is delivered for quick analysis to the olfactory region. Interestingly, alligators’ long noses also function like gas chromatographs!

.png)