The Sanctuary Papers - April 2023

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 4,

April 2023

Text By Shatakshi Gawade & Illustrations by Swadha Pardesi

The flowers of the endemic orchid Phalaenopsis speciosa are like the outcome of a child's gleeful artwork – haphazardly painted blotches, streaks and patches of rosy-purple on fleshy white petals, which means that no two plants have the same flowers. Apart from its five identically shaped petals, the fragrant flower has a sixth oblong petal called the ‘labellum’, protruding like an extra finger from its centre. The orchid blooms between late spring and early winter, and grows in clusters on an almost 0.3 m.-long inflorescence. Like other epiphytic orchids, this herbaceous (non-woody) plant hangs off trunks, with four to five fleshy leaves growing to a dark green hue, reminiscent of humid rainforests. P. speciosa, considered to be synonymous with Phalaenopsis tetraspis, is endemic to Great Nicobar Island, and was first described far back in 1881.

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

Finding A Damsel(fly) With Prehistoric Roots

The Libellago balus, a damselfy endemic to Great Nicobar Island (GNI), was rediscovered on the island after being known only from museum specimens. The species was reported in a paper released as recently as 2023, adding to the understanding that the southernmost tip of India still has much unknown and undescribed biodiversity. This damselfly has ethereal, translucent wings tipped with a glorious purple patch, and a segmented, slender fiery red abdomen. Very little is known about this insect of the order Odonata, and its limited numbers has earned it a place as an endangered species in the IUCN Red List. There are at least 24 species of odonata fauna on GNI, of which three are endemic.

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

If you are lucky, you might see the L. balus in its habitat of forested streams that have a good canopy cover, or sitting delicately on in-stream boulders and twigs hanging precariously over waterbodies. In case you find it hard to differentiate between damselflies and dragonflies, the other similar-looking insect of the Odonata order, remember that the latter have stockier bodies than the former. Dragonfly wings remain outstretched at rest whereas damsefly wings are kept closed. Seeing any Odonata fauna is like looking into prehistoric times – fossils of this ancient order of insects have been found to date back to the Permian era from 250 million years ago!

Would the Nicobar Flying Fox Like its Name?

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

Would the Nicobar flying fox Pteropus faunulus be disappointed that it has been named after a terrestrial mammal instead of a name it can call its own? So what if it has an uncanny resemblance to a fox? One might think that its endemic, endangered status would earn it a lovely, exotic name, more suited to the Great Nicobar Island, where it lives. The Nicobar flying fox was first described in 1902 by G.S. Miller, and rediscovered after over a century in the Nicobar Islands by Dr. Bandana Aul Arora and her team during a survey to record bat species and their habitats. The Nicobar flying fox is a fruit bat – it feeds on fruit and nectar, and is nocturnal. The Pteropus faunulus is also one of only two known solitary roosting bats of the Pteropus genus – the other is restricted to the American Samoan Islands – and the only Pteropus species in India. It has been hunted by Indigenous tribes as well as settlers on Great Nicobar. Unlike its generic name, this fact is not so surprising, considering the Wild Life (Protection) Act (1972) categorises all fruit bats as vermin, and has placed them in Schedule V. Despite being endangered, the Act excludes it from legal protection. The primary causes for reducing numbers of this species are hunting by local communities and loss of habitat on account of clearing of its forests for coconut plantations and settlements.

Did You Know?

The Nicobarese, the Indigenous people of the Nicobar Islands, believe that there are two kinds of bats – big and small. While local dialects vary from island to island, big bats are called mok-ne-aka law (big fruit bat) and medium and small fruit bats are called mok-ne-aka peh in Central and Southern Nicobar Group Islands. Hinglenea is the name for the insect eating microbats.

A Case Of Mixed Identities

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

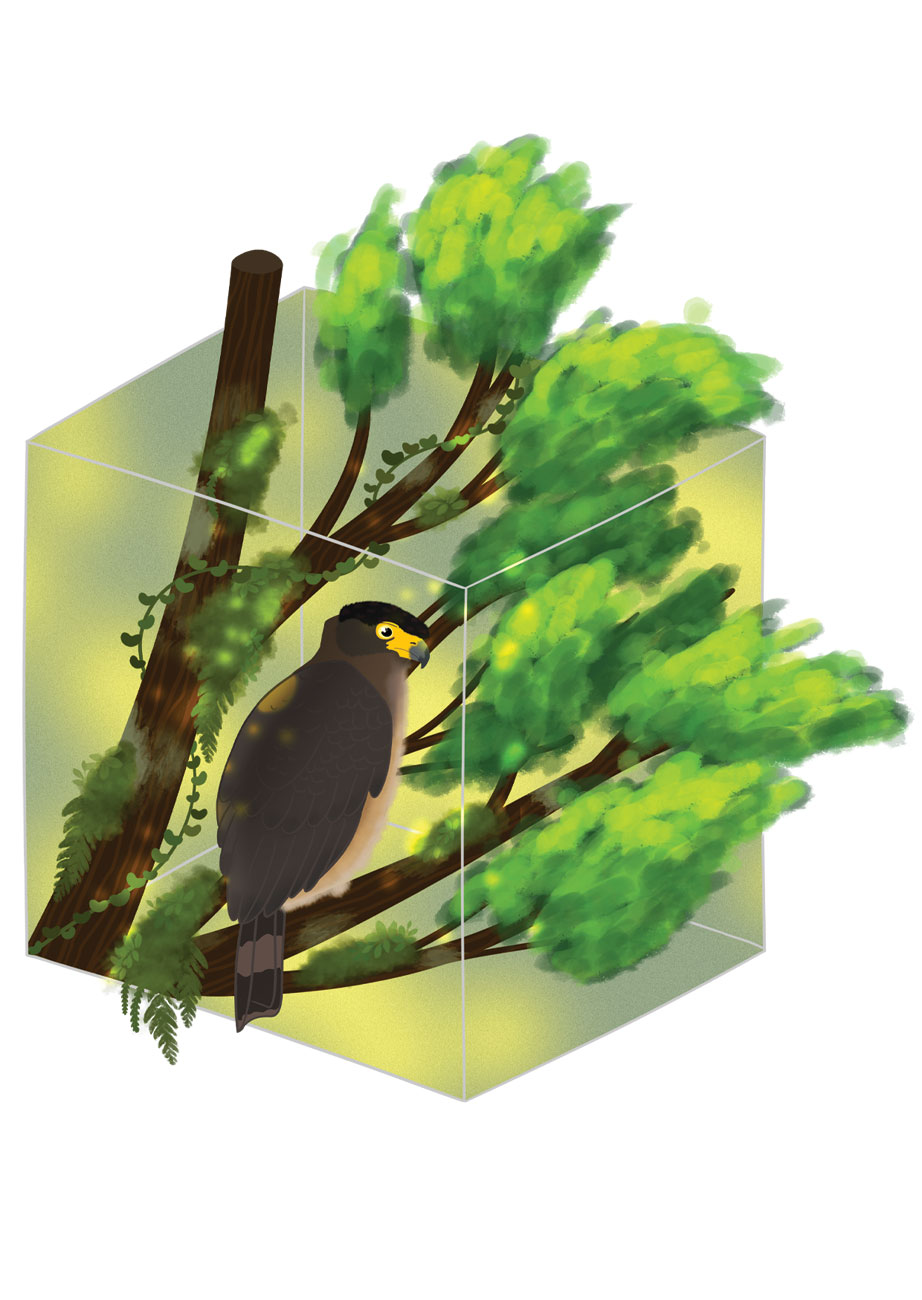

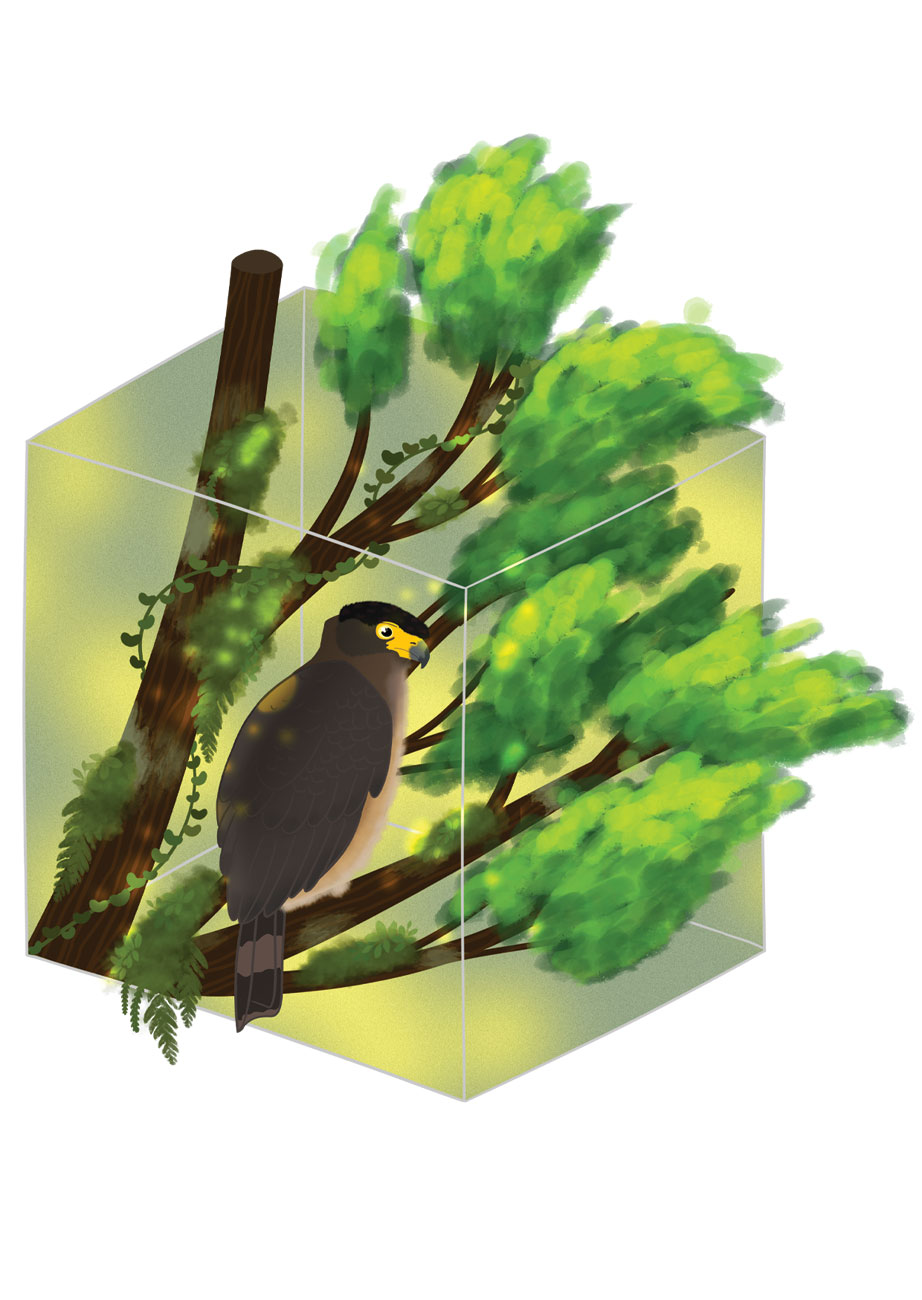

For the longest time, the Great Nicobar Serpent Eagle Spilornis klossi was considered a subspecies of the Crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela, but is now identified as a separate species altogether. It is the smallest known serpent eagle – it can be distinguished by its size, pale brown plumage, unmarked cinnamon-buff breast and a short black crest tipped with rufous, and a black crown, which looks a lot like a wig! Between its sharp beak and killer eyes is a sunny yellow patch, which matches the colour of its legs. It is also known as the South Nicobar Serpent Eagle, and is endemic to forests of Great Nicobar and Pujo Kunji, Little Nicobar and Menchal. It is found in primary forest, often in the canopy up to 600 m. above sea level, and also in regenerating habitats and grasslands. It most likely feeds on reptiles, rodents, and birds. Like many endemic species on Great Nicobar, the Great Nicobar Serpent Eagle is threatened by habitat loss. The settlements on the Nicobar Islands are already a threat to this small bird of prey, and planned development projects could damage its habitat further. The decreasing numbers have put it in the near threatened category in the IUCN Red List.

A Darwinian Déjà Vu

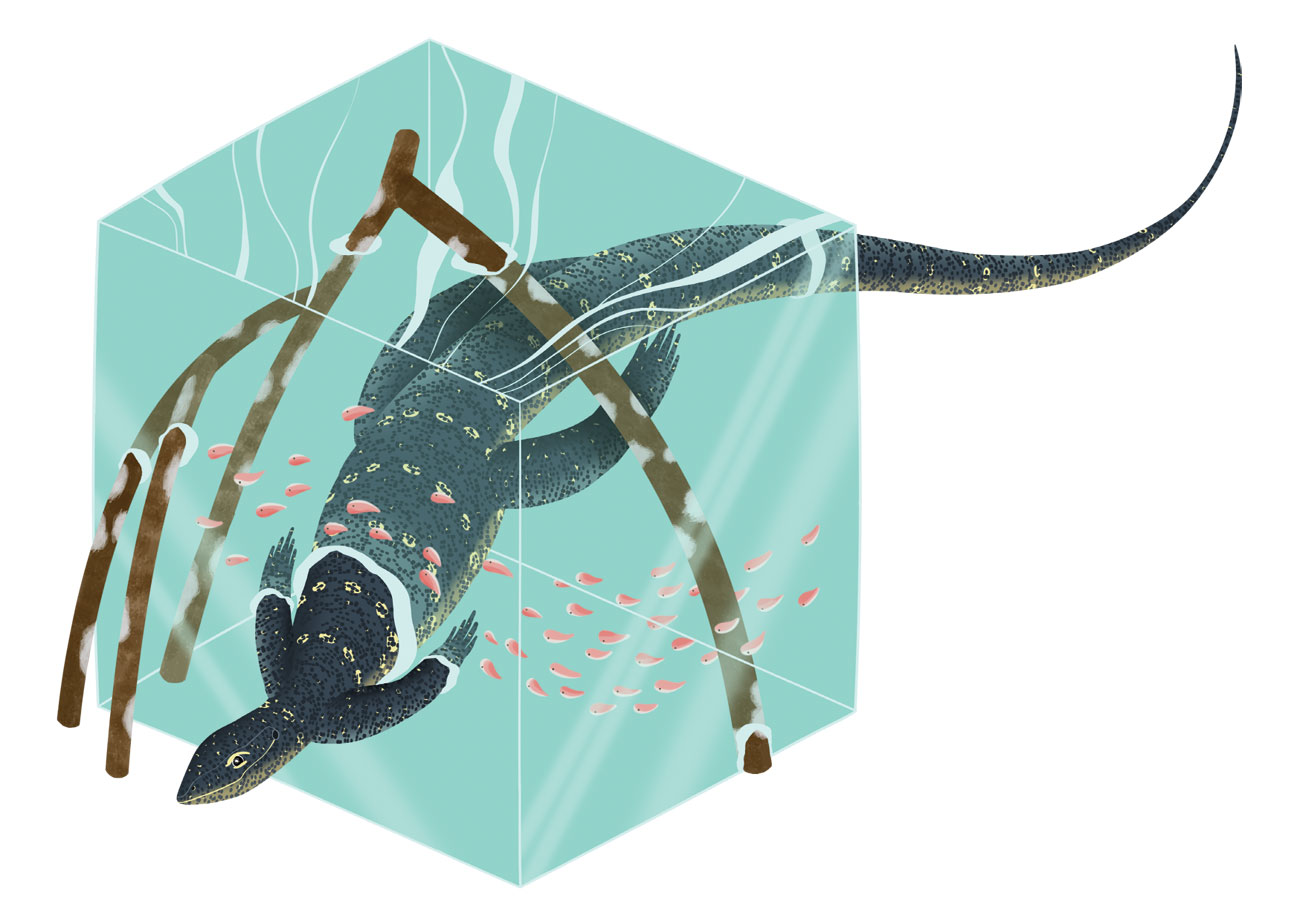

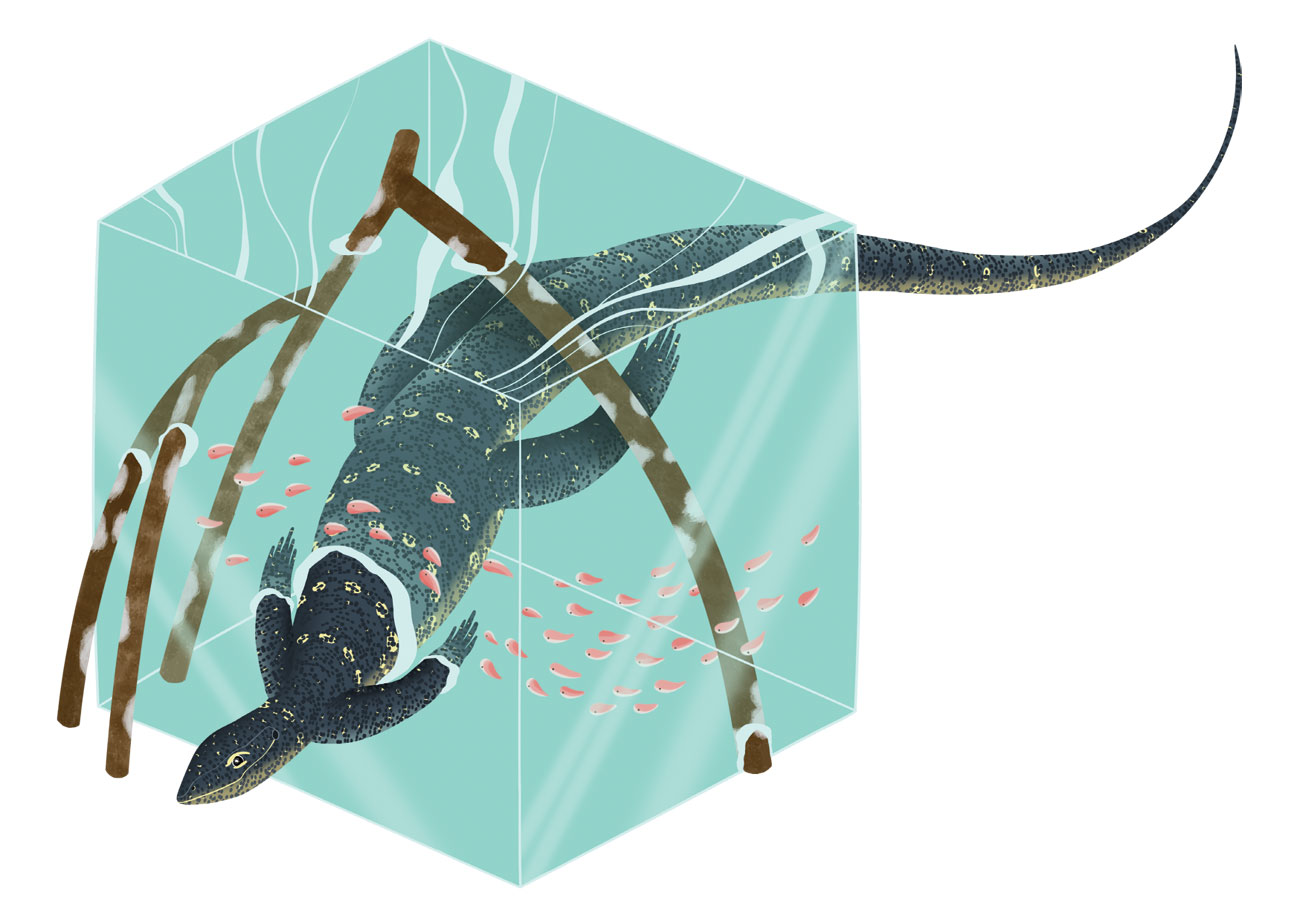

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are home to the endemic Andaman water monitor lizard Varanus salvator andamanensis. Curiously, the central and northern Nicobar Islands do not host this giant lizard, but are home only to the Southeast Asian water monitor V. s. macromaculatus. Researcher Indraneil Das suggested in 1999 that reptiles such as the Andaman water monitor, the skink Lipinia macrotympanum and others could have reached the Andaman Islands when they were connected with Arakan Yomas (the Rakhine Mountains of Myanmar) when global sea levels were much lower than they are now, about 2.58 to 0.011 million years ago, and populations could have also spread to the Nicobar Islands. The dispersal of these reptiles on different islands can also be attributed to ocean currents. The presence of two closely related species is a classic example of allopatric speciation – species separated by geographic barriers – that prompted Darwin to formulate his theory of evolution by natural selection. If intergenerational déjà vu were a thing, researchers today would certainly experience it while studying species in remote locations such as Great Nicobar.

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

The Andaman water monitor lizard has to be carefully observed to differentiate it from other monitors – it has a black back decorated by 17-18 horizontal rows of light yellowish dots, known as ocelli, right from its tip to the end of its tail. These spots also sporadically cover its limbs and tail. Researchers have observed that these spots fade with age. V. s. macromaculatus meanwhile has a greyish or brown body with a higher average scale count. Scientists are still wondering about the similarity of these water monitor species, and if they could even be the same species. This would require in-depth studies of older museum specimens as well as DNA analysis.

Did You Know?

The Nicobar long-tailed macaque has cheek pouches like all other macaques, baboons and guenons – the other members of its subfamily Cercopithecine. These pouches extend down the side of its neck and allow it to collect and temporarily store food such as nuts, seeds and fruit. The pouch has enzymes, which break down the food and begin digestion. Insects however, are gulped down in a blink!

A Frog That Chuckles

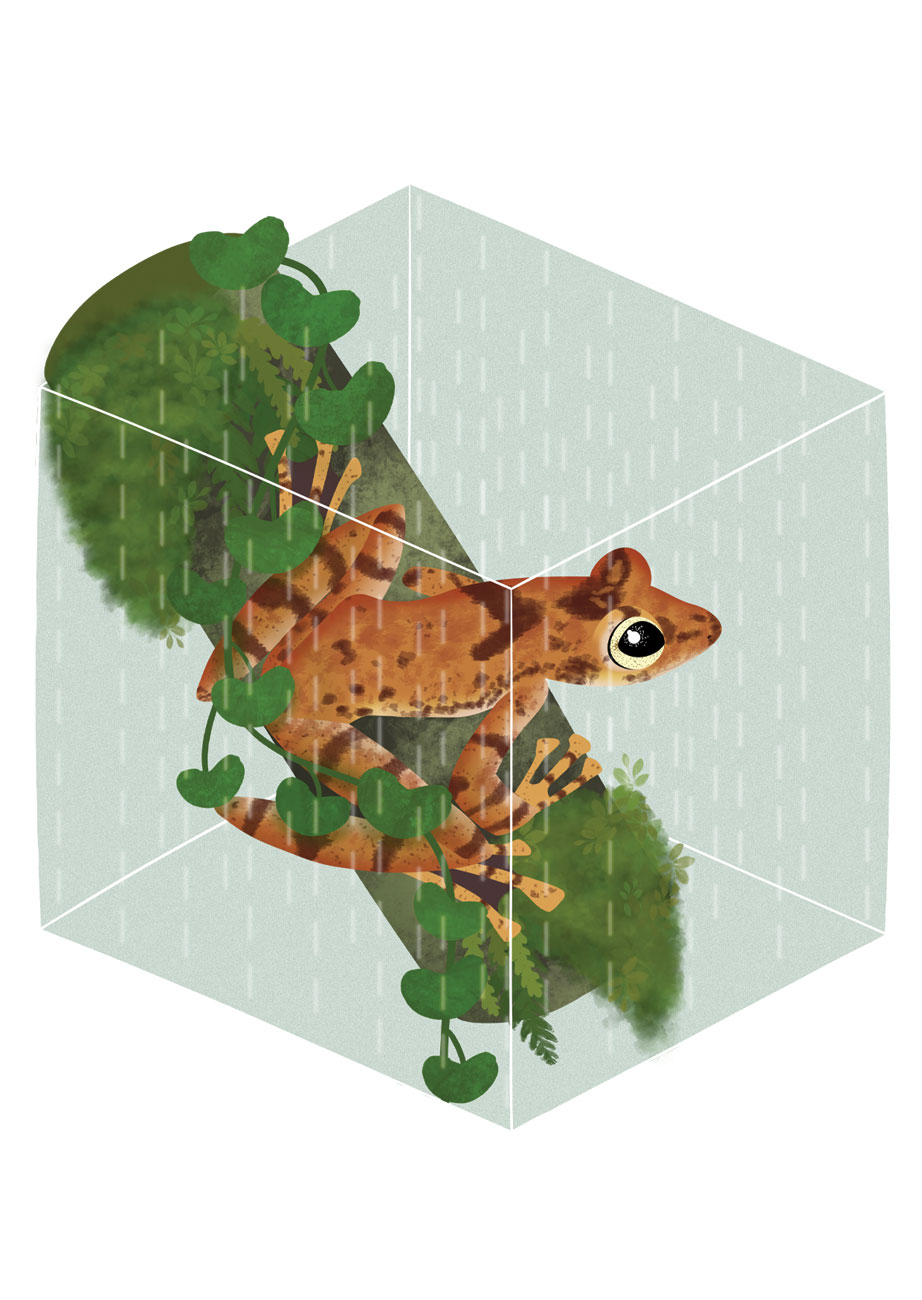

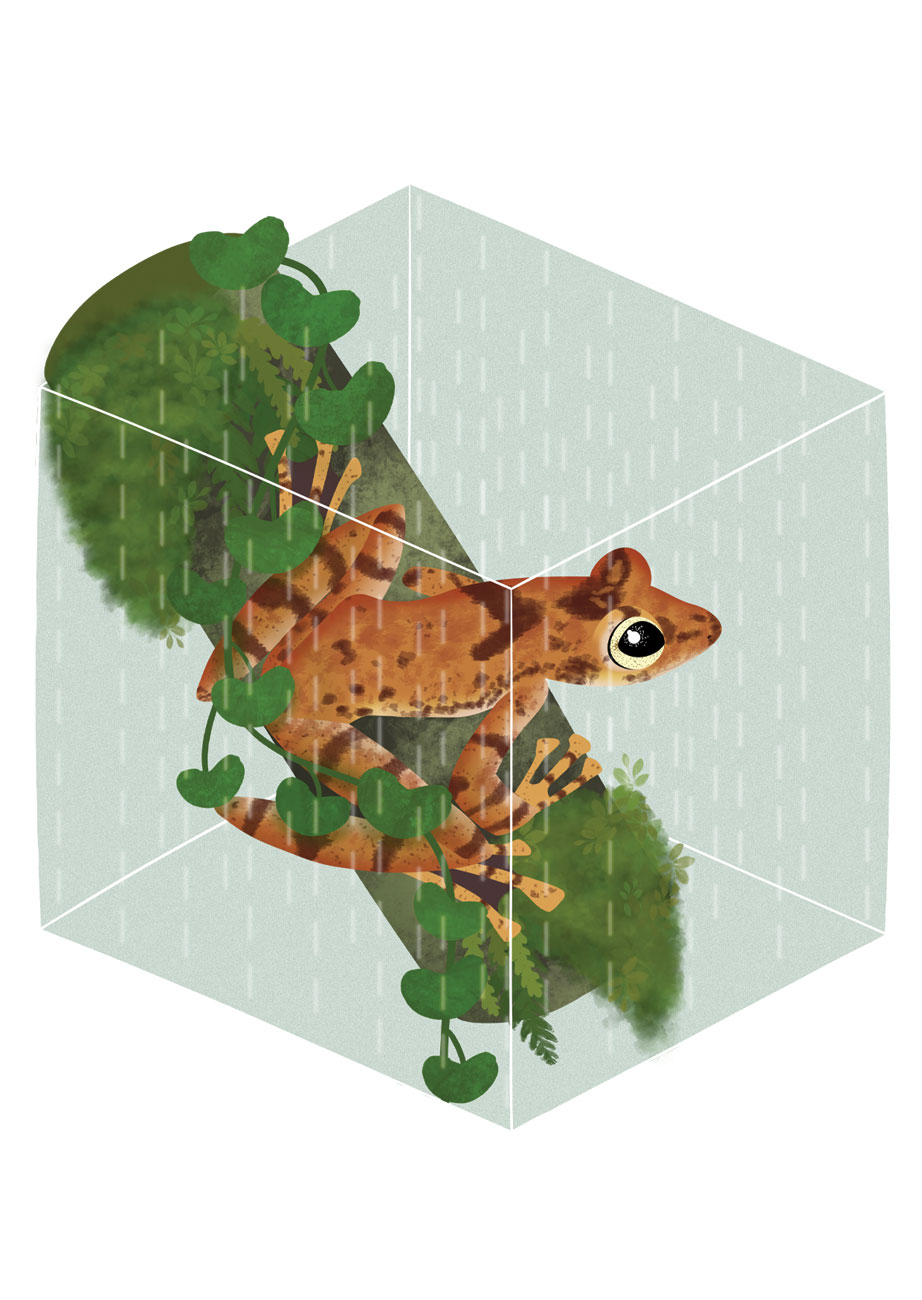

Like many species on Great Nicobar, the Nicobarese tree frog Polypedates insularis is endemic, endangered and poorly known. In 2018, 23 years after it was first described by Indraneil Das in 1995, scientists made a detailed description of its morphology, breeding and distribution. This long gap between the two instances goes to show how remote these islands are for continuous research, and how much more biodiversity wealth is yet to be discovered. Though it is the only representative of its family Rhacophoridae on these islands, this amphibian family is highly species rich in other islands of Southeast Asia such as Sumatra, Borneo, Java and Philippines.

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

The Nicobarese tree frog is commonly found in evergreen forests, plantations and among vegetation near human habitation. Its colour varies from pale to dark brownish, and males are smaller than females. Some individuals of this species have a distinct hourglass shape etched onto their backs. Rain seems to be an aphrodisiac for these amphibians – they breed and court each other during the monsoon as well as during (late May to September) as well as sporadic, aseasonal rainfall between the months of January and March, and they have been observed to mate near still freshwater. The result of these amorous interactions is a foamy, hemispherical nest that yields light brown tadpoles. The researcher Sumaithangi R. Chandramouli describes their low pitch calls as trk… trk… trk… sounds, followed by a series of chuckles!

A Stoic, Resilient Reef-Builder

Illustration: Swadha Pardesi.

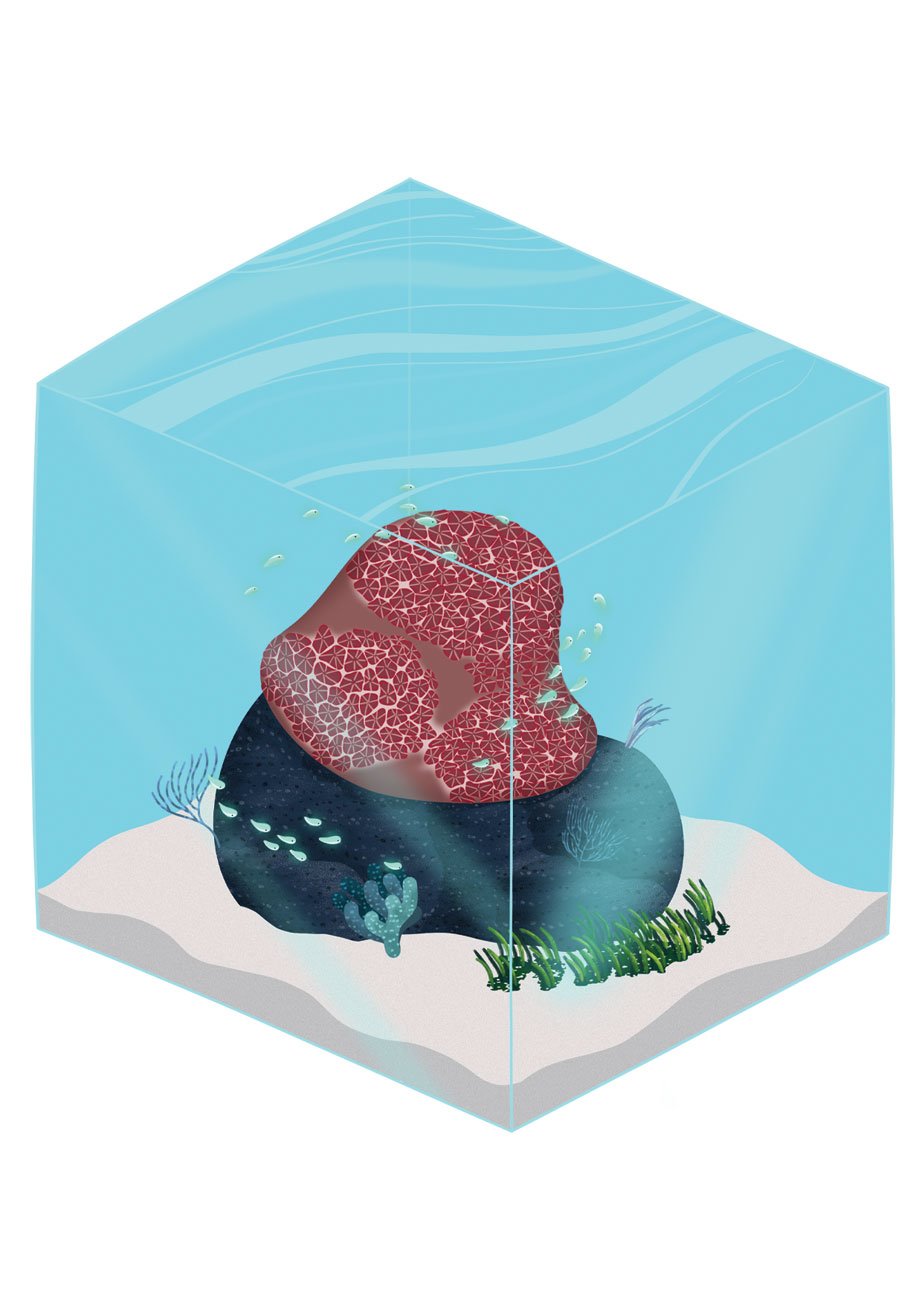

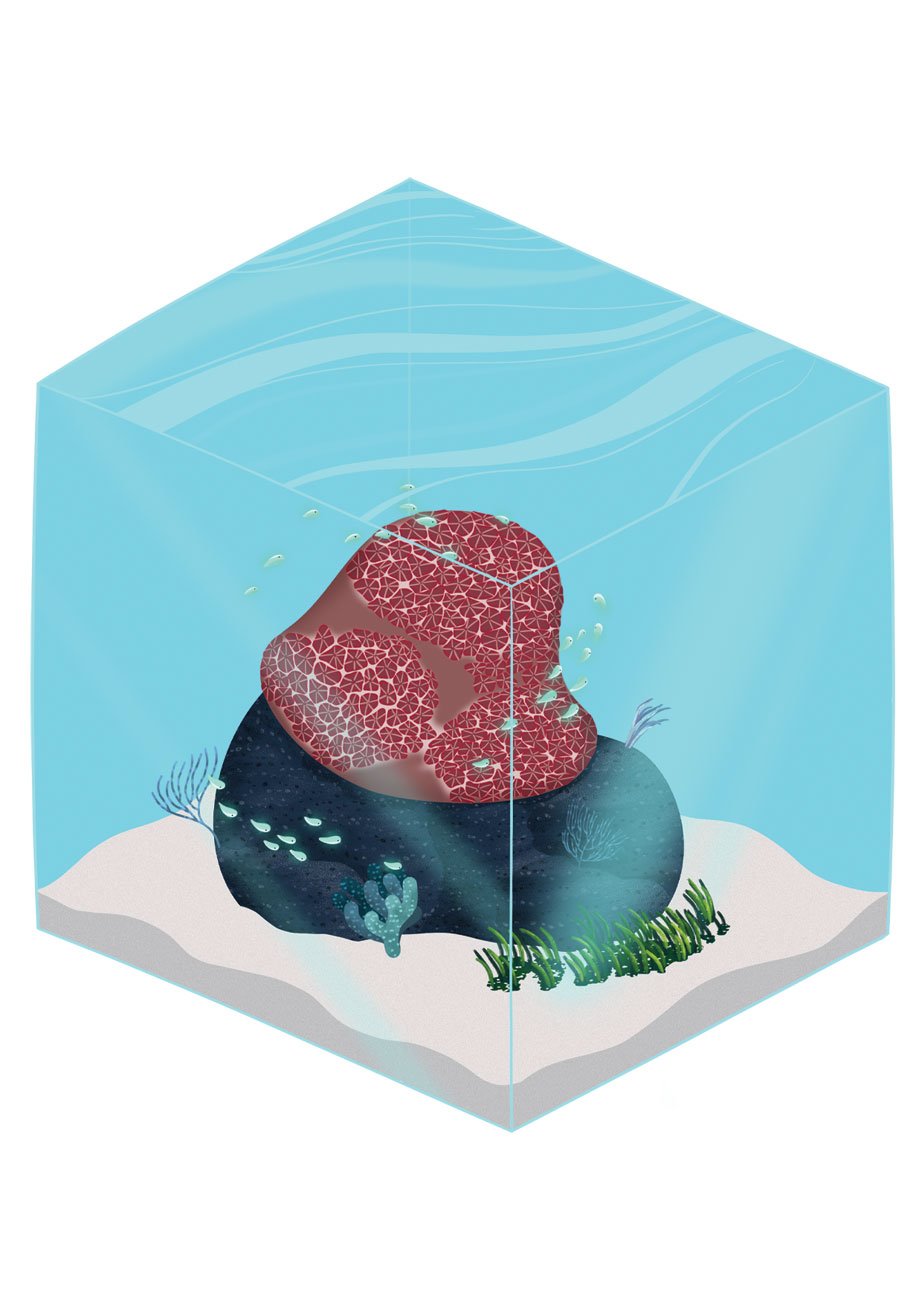

Coral reefs are so rich in species diversity that they are known as the ‘rainforests’ of the ocean. They directly and indirectly sustain over five crore people, and protect the coast from natural disasters. The reefs in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are biologically more diverse than other Indian reefs due to their geographic proximity and connectivity to the Indo-Pacific coral triangle (a marine region comprising the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands). There are at least 273 species of scleractinian corals in the Great Nicobar Island, which is around 47 per cent of Indian scleractinian species. They are known as stony corals as they build themselves a hard skeleton of calcium carbonate. An individual is known as a polyp, and it lives either solitarily or in colonies. The polyp lives only in the topmost part of the mature exoskeleton, while the rest of the coral is non-living. This reef-building characteristic makes them extremely important for the underwater ecosystem. They have been dominant reef-building organisms for the past 240 million years. Scleractinian corals have a skeleton with radial structures called septa, which are arranged in multiples of six. The two inflection points in the life of the scleractinian corals of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are the 2004 earthquake-cum-tsunami, which devastated reef habitats, and the 2010 mass bleaching event, which damaged the health of scleractinian corals. However, the corals were resilient – despite considerable damage in both these events, they continued growing in favourable circumstances.

Recent discoveries in Great Nicobar Island

Insects: The moths Garudinia shompen (2022), Trilocha nicobar (2021) and Cyana conclusa (2020); scarab beetle Clyster galateansis (2020); the longhorn beetle Sarmydus nicobarensis (2019); whitefly Asialeyrodes nicobarica (2019); mayfly Choroterpes nicobarensis (2017); and damselfly Nososticta nicobarica (2017).

Reptiles: The geckos Gekko stoliczkai (2021) and Cnemaspis nicobaricus (2020), and the skink Eutropis dattaroyi (2020).

Aquatic: The spangled flatworm Acanthozoon fuscobulbosum (2018), and the flatworm Pseudoceros galatheensis (2017).

And more…: The frog Microhyla nakkavaram (2022), flowering plant Septemeranthus nicobaricus (2021), and lichen Leiorreuma nicobarense (2017).

Did You Know?

The dugong Dugong dugon is the state animal of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and is found mostly in the waters around Great Nicobar Island, in north Andaman and Ritchie’s Archipelago here. This large, nomadic marine mammal is also known as a sea cow or locally as pani suwar (sea pig). Despite having a wide range in Indo-Pacific tropical waters, it is vulnerable to extinction on account of hunting, pollution and habitat loss.

Swadha Pardesi is a freelance digital illustrator in wildlife and nature conservation. She likes to use her skills of journalistic inquiry, understanding of ecology, visual art and imagination to express wordy concepts via aesthetic science communication illustrations. She is subtly political in her work, which is deeply inspired by volunteering at Let India Breathe, a collective of climate change campaigners and communicators. When she was 19 years old, she stayed at ARRS Agumbe, Karnataka, for a month as a volunteer. It was her first time being in such a wilderness and one of the most immersive experiences of her life. To this day, she draws inspiration from her time there and pours it into her illustrations. Animals and habitats, one cannot exist without the other. Thus, she wanted to share glimpses into the biodiversity hosted by Great Nicobar Island in her creations for Sanctuary Papers.