The Majestic Bhatoris of Pangi Valley

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 12,

December 2020

By Monika Sharma, Rupali Sharma, Himanshu Bargali, Manisha Mathela and Amit Kumar

The Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) is inhabited by various ethnic communities. Living relatively in isolation, their lifestyles are very much connected with the rhythm of nature and they are a bastion of traditional knowledge that is crucial in the fight for our wildernesses, and in the larger fight against climate change.

Some communities are the Gujjar, Bot, Bakarwal, Brokpa, Balti, Purigpa, Gaddi, Sippi, Changpa, Mon, Garra and Beda in Jammu and Kashmir, Pangwal and Bodh (also known as Bhot or Bhotia) in Himachal Pradesh, Bhotia, Tharu, Raji, Jaunsari, Buxa and Gujjar in Uttarakhand, Limboo, Lepcha, and Bhutia in Sikkim and Monpas, Sherdukpen, Apatani, Adi, Galo, Idu Mishmi, Nyishi, Tagin, Nocte, Wancho, Khampti and Aka in Arunachal Pradesh. To study the high value of threatened Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) in Lahaul and Pangi valleys in Himachal Pradesh as a part of the SECURE Himalaya project, we, a team of five from the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun, stayed in Pangi for more than six months during 2019-2020.

As we drove from Koksar, the gateway to Lahaul valley, we gawked at the splendid beauty of the scenic mountains. The route towards Killar in Pangi valley is not one for the fainthearted, with dangerously narrow paths and hairpin bends alongside the Chenab river make this one of the most dangerous roads in the world. Pangi valley is home to various ethnic communities, of which Pangwal and Bhot are native here, as well as stunning biodiversity.

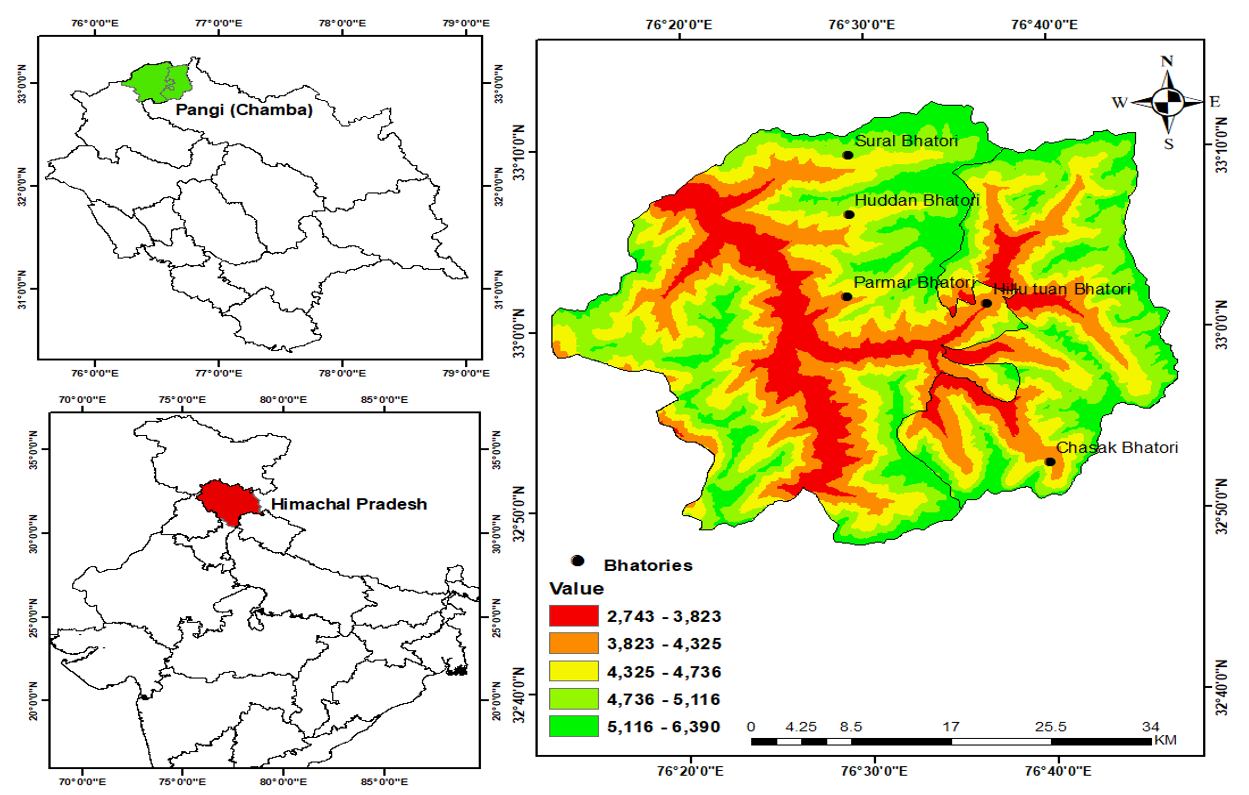

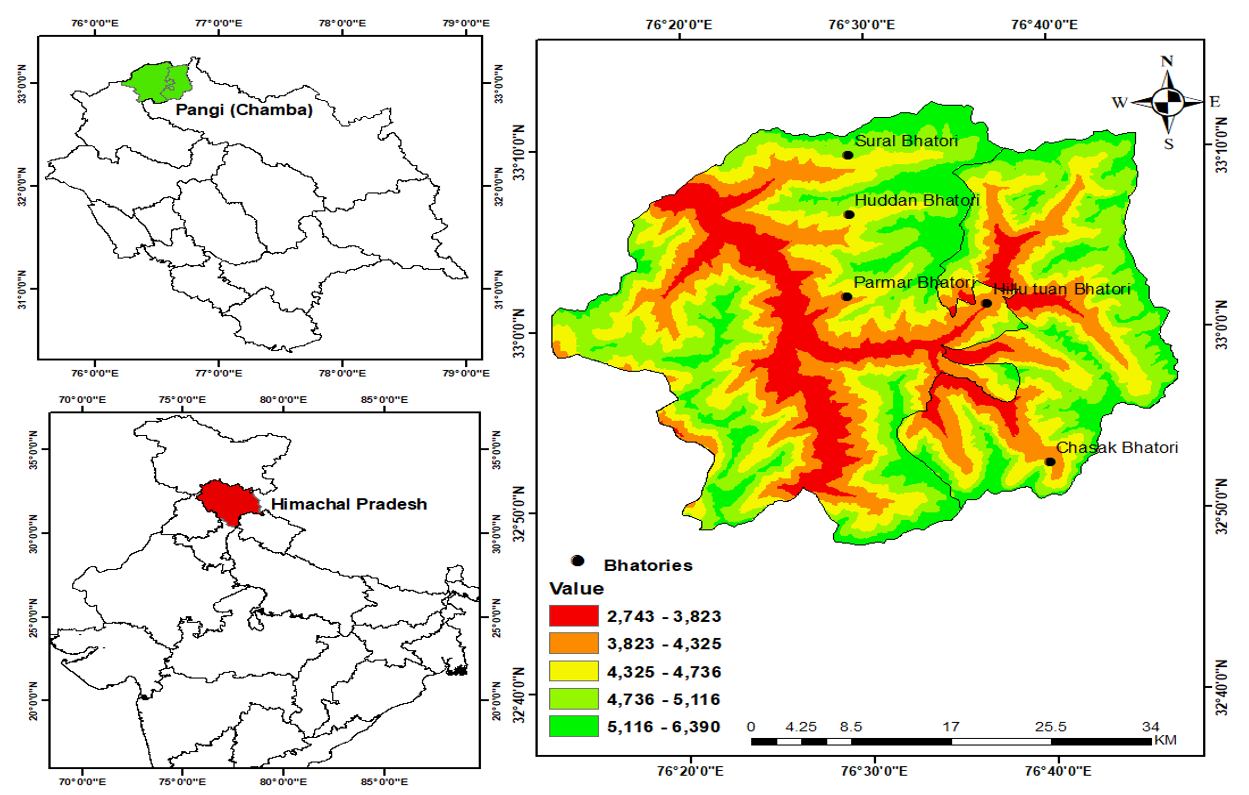

Geographically, Pangi valley (31.5892° N, 78.2775° E) falls under the semi-arid zone of the Himalaya. A total of 106 villages in the valley support an estimated human population of 18,868. The villages are sparsely populated; houses are concentrated in small hamlets within, from Luj village at the lowest elevation (3,149 m. above mean sea level or masl), to Chasak Bhatori village at the highest (4,285 masl). The Pangi valley is sub-divided into five Bhatoris (remote alpine regions inhabited by Mongolian Bhots), namely Hudan, Sural, Chasak, Parmar and Hillu Tuan located in the alpine and sub-alpine regions. Each Bhatori has its own ‘adhwari’, summer settlements of Bhots during the summer to late autumn season, predominantly for livestock grazing and collection of milk, ghee and buttermilk to be consumed in the following winter. Folklore has it that Pangwals of Pangi, were the criminals of Chamba darbar who were ostracized and sent to Pangi on exile, women were relocated permanently here for their safety during annexation.

Forest vegetation in Pangi valley majorly consists of species like Betula utilis trees. Photo: Amit Kumar

A map of the various Bhatoris in Pangi valley.

Primitive agricultural practices, such as single crop pattern and livestock rearing form the most important sources of sustenance and profit generation for the locals. Interestingly, ‘churu’, a hybrid of the Yak and domestic cattle, is unique to this region and fulfills the requirement of dairy products and meat. The primitive crops grown in the valley were wheat, maize, barley, phullan, bres and siul. Bres and phullan were the traditional varieties that were planted before the government-aided supply of grain and seeds started. Now, vegetable crops such as potato, pea, cauliflower, rajma, lettuce and local fruits such as plum, apple and apricot are more widely cultivated. We were fortunate enough to try Chasak ke laal aaloo, the well-known indigenous red skinned potatoes found growing commonly in Chasak Bhatori.

Forest vegetation in Pangi valley is mainly characterized by species such as Abies spectabilis, A. pindrow, Betula utilis, Cedrus deodara, Juniperus sp., Picea smithiana, Pinus gerardiana, P. wallichiana, Taxus wallichiana, Populus sp., and Salix sp. The forest areas along the Bhatoris are dominated by beautiful patches of bhojpatra Betula utilis, which locals utilise as fodder, fuelwood, medicine, and for religious rituals, resulting in the heavy logging of this tree. Recently, a ban has been imposed on entry into the Reserved Forest area to promote the rejuvenation of forest. The forest department issues permits for the collection of medicinal plants and non-timber products to the locals, usually at a minimal cost. However, no clear estimates are available on the extent of the extraction of medicinal plants.

While trekking towards the Bhatoris, we were dejected by the non-availability of basic necessities such as medical and educational facilities to the locals. The Tibetan Medicinal System or Amchi system of medicine (Sowa-Rigpa) is a prevalent traditional healthcare system practiced by local healers (known as Amchi or Vaidya) since time immemorial. The inhabitants depend on them for the treatment of various ailments. MAPs such as jangli lehsun Fritillaria cirrhosa, atis Aconitum heterophyllum, bankakri Sinopodophyllum hexandrum, kadu Picrorhiza kurroa and kala zeera Bunium persicum have a high market demand locally as well as globally. Owing to their immense medicinal properties, these MAPs are traded like hot cakes in the market whereas their over-harvesting, and premature and illegal collections have led to decline in wild populations.

The seasons regulates the activities of the villagers, with snow curfews imposed during winters. People spend most of their times in weaving pattus (shawls), chadrus (blanket) and thobis (mats made of goat hair), apart from social activities like drinking, singing and dancing. During the summer season, the locals across the entire valley are relatively active, usually seen farming and cattle herding. People are also employed in different capacities at this time, as daily wage workers in construction and development activities in the valley.

Churu, also known as Dzo, is a hybrid of Yak and domestic cattle raised in Pangi valley. Photo: Amit Kumar

Bhots harvest red-skinned potatoes in Chasak Bhatori. Photo: Monika Sharma

Furthermore, Praja Mandal, a local archetype in Pangi valley has been successful in conserving the wild resource base of not only MAPs but also their associated natural resources such as fuelwood and fodder, by designating forest or community areas as separate conservation units. Praja Mandal or 'community federation’ has been a part of the Indian Independence movement since the 1920s. It is governed by a village council with one member from each family, and is an entirely community-based body. The local inhabitants in a Praja Mandal have their rights as well as restrictions to the forest. There is an appointed ‘pradhan’ (head), ‘up-pradhan’ (sub-head), cashier, secretary, ‘chad’ (messenger), ‘batwar’ (messenger) and ‘swar’ (kitchen or cook). The Praja Mandal through its council imposes a penalty to offenders. Boycotting persons from their rights is a major penalty of this system along with the deposit of tangible goods. The penalty can be determined case by case such as Rs. 5,000, 40 kg. atta, 10 kg. ghee and one goat as a penalty for cutting a tree or harvesting of medicinal plants from their community land. There can be more than one Praja in a Panchayat. This unique system is instrumental in ensuring the sustainable utilisation of natural resources in the IHR.

The Pangi valley has a single Protected Area - the Sechu Tuan Nala Wildlife Sanctuary which was notified in 1973 and has an area of about 102 sq. km. Among the Bhatoris, Chasak Bhatori is confined to the boundary of this Sanctuary. Bhots of Chasak Bhatori are acquainted with the wildlife in the area and also contribute effortlessly to the conservation of threatened medicinal and aromatic plants along with other flora and fauna.

These ethnic communities, despite struggling with a poor economy, harsh terrain and a severe lack of basic amenities, possess rich cultural heritage that must be safeguarded with appropriate measures planned by the government. Capacity building, provision of education, health security and alternative livelihood opportunities are paramount to empowering the local inhabitants with the means to flourish and preserve their traditional ways.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director and Dean, WII, Dehradun, for institutional support. We would like to acknowledge United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Global Environment Facility (GEF) for funding and Ministry of Environment Forest & Climate Change (MoEFCC), New Delhi and Himachal Pradesh State Forest Department for constant support and guidance.