The Magic of Mohan

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 6,

June 2020

By Indranil Datta

If you’ve sampled the writings of Jim Corbett, the name ‘Mohan’ (also spelled Mohaan) might ring familiar to you. The late hunter-turned-conservationist immortalised the village of Mohan in one of his globally-acclaimed classics The Man-eaters of Kumaon, in the chapter ‘The Mohan Man-eater’, in which he tracks and slays a feline gone rogue. Though the story had its origins in Mohan, much of the chase plays out miles away from where the saga began, which Corbett recounts in horrifying detail:

“There was no such happy awakening from the nightmare of that unfortunate girl, and little imagination is needed to picture the scene. A rock cliff with a narrow ledge lying partly across it and ending in a little depression in which an injured woman is lying; a young girl frozen with terror, squatting on the ledge, and a tiger slowly creeping towards her, retreat in every direction cut off and no help at hand”.

Although the Mohan of today bears many a change, its setting – dominated by shrubs and floodplains and isolated patches of jungle – still harks back to the days of yore. The weathered walls of rock still surge up sheer from the furthest reaches of the Kosi’s floodplains, which stretch to the base of the Himalayan foothills towering over Mohan. Even today, one might catch a glimpse of a ‘tiger slowly creeping’ through the foliage. One can but hope that it creeps in search of its usual prey, as alleged instances of man-eating still do take place – the last a decade ago.

My experiences in the Corbett National Park were limited to its tourist zones, where gypsies plied back and forth in frenetic search for the tiger. Knowing no better, I fell in tow with these tiger-chasing throngs, till matters came to a head. The usual clamour of the crowds had escalated to a deafening din. In a fit of rage, I vowed to never enter the park on four wheels again.

.jpg)

A chapter from Jim Corbett's book The Man-eaters of Kumaon immortalises the village of Mohan, in which he tracks and slays a feline gone rogue. Though the story had its origins in Mohan, much of the chase plays out miles away from where the saga began. Photo: A.G.Ansari.

The Road Less Travelled

I still wanted to explore the wilds and be amongst the cats, but minus the ruckus. I had little clue if this was even possible in a big-ticket park like Corbett, and thus sat slouched in my chair, pondering the viability of my plans. I was soon joined by Puran and Vivek, companionable staffers of the lodge in which I was staying. They took stock of my grievances, and mulled over the issue in hushed exchanges. A minute later, without divulging any details, they asked me to be up at the crack of dawn with my walking shoes on.

I welcomed the coming of dawn as a sleep-deprived bag of nerves, raring to get my legs going. Vivek and Puran were no strangers to Mohan’s terrain, having grown up a stone’s throw away from the demarcated boundaries of the park. This gave them a keener jungle sense than I could ever dream of possessing, and helped amplify my courage manifold. But as the events of the day would later prove, even a man steeped in jungle-craft is, more often than not, a poor match for the ways of the wild.

We walked single file, with Vivek in the front and Puran bringing up the rear. I felt an added measure of safety as I ambled along between the two. I tried in vain to complement their awareness of the jungle, but my city-bred senses were like a worn-out pebble to their scalpel-like instincts.

Birding on foot in the Mohan jungles offers sightings such as this Spot-bellied Eagle-owl flaunting its kill, a Grey Hornbill, in its talons. Photo: A.G. Ansari.

The triangular cluster of trees – easily the most striking feature of the land – had seemed like a benign profusion of trees from afar, and not the eerie, impenetrable bastion of green it had morphed into on closer inspection. As the magnificence of my surroundings began to seep in, a strident shriek pierced the morning air – a chital warning us of a predator on the prowl.

We marched ahead, stomping our way to a sparser stretch of ground to gain a wider view of the surroundings. However, the only clues we unearthed were the ones that lay underfoot: crisp paw-prints, indicating a tiger’s all-too-recent passage. There wasn’t much of a trail to follow, as the pebble-strewn surface hadn’t allowed for multiple impressions. Thus, in the absence of any clear-cut markers, we thought it best to abandon our current position, and resume our search from higher ground.

The quickest way to accomplish this was to scramble up a ragged precipice with a few precarious footholds for purchase, and having cautiously navigated our way upwards, we set our sights on the floodplains below. Minute after minute dragged on, but not a leaf stirred. In view of the prevailing lull, we decided to head back down, to scan for further clues. However, this time, a more sensible route of descent was chosen… a dry watercourse, or a nullah.

A Nail-Biting Experience

While the nullah proved considerably easier for our bodies to negotiate, our minds felt ill-at-ease in this cloistered jungle alley. And halfway through our descent – as if our sense of foreboding was prescient – a chital let out a hollering cry, rousing the jungle to life again, from perhaps some 30 m. away. We wordlessly broke into a trot, and emerged from the nullah into one of the pebbled clearings we’d crossed before. We combed the tableaux of yellows and greens and whites for a flicker of yellow and black, but the only thing to meet our eyes was the idyllic jungle landscape, cloaked in the same garb of secrecy, without so much as a startled deer in sight.

Sapped of ideas and steam, we chose to call it a day, and were on the retreat, when a new find put us in a fix. Plastered onto an older set of prints left by the soles of my shoe, were those of a tiger’s, and unlike the ones we’d identified before, the width of the pad was noticeably smaller.

The spoor – made only minutes ago – was undoubtedly fresh, for a steady drizzle, pouring for over half an hour, hadn’t distorted its form. Surprisingly, the tracks were pointing in the same direction as ours – towards the thickets and away from the nullah. This was just the clue we needed to piece together the puzzling events of the last 30 minutes.

If our conjectures were right, then in all probability, this is what had transpired out of our sights: before we began our descent through the nullah, a tiger cub lay safely ensconced in its midst, but as we began to stumble towards its chosen refuge, it made a break for the exit, bounded past the clearing and darted towards the closest available cover, spooking a bamboozled chital in the process.

As far as appetisers go, the jungles of Mohan had whipped up a nail-biter. Their mesmerising vistas and big-cat theatrics had left me craving for more.

The tiger cub's pug mark spotted by the author during a walk in the jungle. Photo: Indranil Datta.

Experiencing Mohan

Over time, I grew to discover that the jungles of Mohan harboured much more than the striped cat family. Abdul Ghaffar Ansari, who owns a lodge in the area, has been a keen observer of the wildlife in his backyard for almost two decades.

Though a hotelier by profession, Mr. Ansari has also established his credentials as a conservationist by aiding the park authorities. He understands as well as anyone that the benefits of safeguarding these forests don’t just confine themselves to an isolated jungle realm, but spill over to support the larger interests of the Kosi River Corridor – a crucial, contiguous belt of fringe habitat used as transit points for animals moving between the Corbett Tiger Reserve and the Ramnagar Forest Division. The security of the landscape, like any other, hinges on the security of its parts, and Mohan being one of them, deserves all the protection it can muster.

Wild inhabitants

Wild inhabitants

In 2013, while out birding, Mr. Ansari made a stupefying find in the jungles of Mohan, capturing photographic evidence of a smooth-coated otter wading about an isolated pool of water. Although these creatures are known to inhabit the waters of the Ramganga flowing through the Corbett Tiger Reserve, their presence in the Upper Kosi Range hadn’t been recorded for over half a century, until Mr. Ansari’s remarkable rediscovery. The surprises kept coming. A year later, Mr. Ansari captured a record shot of the Greynecked Bunting – a passage migrant that has only three photographs to its name till date in the Corbett landscape. Raising the hope for further novelties is Mr. Ansari’s cook, who claims to have sighted a hyena in Mohan, although he can offer no direct evidence of his claim. However, the fact that striped hyena presence has been established in the neighbouring jungles of Powalgarh, there is reason enough for one to believe that the cackling canid will find its place amongst Mohan’s growing tally of denizens.

Since my first foray into the jungles of Mohan, sampling its wilds had become a routine indulgence on every visit. But given that the only means of exploring the spaces were on foot, I couldn’t afford to lower my guard however so briefly. This was a lesson driven home, not by the skittish felines, but the burlier residents of the park.

On a pleasant summer evening, lacking my usual company, I set out to scout the jungles of Mohan alone. I wasn’t in the mood for any thrills, wanting to make use of my camera instead. Thankfully, as I approached the woods, I found no cautionary signs of any sort. However, what I found instead, were 20-something cattle heads grazing nonchalantly in the tiger’s domain. Resenting their intrusion upon ‘my’ turf, I sought out a quieter spot, and just as I was about to turn tail, a herd of elephants materialised out of nowhere to amble into the same stretch along which the cattle were grazing. Neither seemed to mind the other’s close company – feeding being the only thing on their minds. As I observed these gentle giants from a safe distance, I thanked my lucky stars for keeping me put, and steering me away from my usual route to spare me the consequences of accidentally crashing an elephantine party.

The occurrence of elephants in Mohan weren’t an anomaly by any measure, as Mr. Ansari can testify. He tells me that the jungles of Mohan double up as a vital component of an elephant corridor. However, denying the elephants an unhindered passage is the village of Chukam, which sits in the middle of the corridor. But astonishingly, as Mr. Ansari points, Chukam isn’t only an inconvenience for the roving pachyderms alone, but Corbett’s dispersing felines as well – a claim underscored by the findings of WWF’s Kosi River Corridor report, which affirms that “these riverine patches serve as stepping stones or stop overs for the spillover population of tigers in the landscape.”

Efforts to relocate Chukam village have been underway since Mr. Ansari initiated a proposal for the same. It now awaits the Chief Wildlife Warden’s approval, and if cleared, will free up a total of 117 ha. for the forest to reclaim.

An elephant slaking his thirst for nutrients at a naturally-occurring salt lick in Mohan.

The Fault Is In Us

Mohan’s jungles aren’t devoid of their pressures, but they’ve managed to escape the two main threats afflicting our fringe forests – poaching and retaliatory killings. The former, Mr. Ansari asserts, is virtually non-existent – a claim I was initially highly sceptical of. He stresses the underlying reasons for this have more to do with Mohan’s lack of access to the traditional illegal trade routes than anything else. Retaliatory killings on the other hand, have been brought to a naught by the united efforts of NGOs such as The Corbett Foundation and the World Wildlife Fund that ensure that the owners of livestock are speedily compensated in the event of a verified cattle-kill, and thus not antagonised by the cats’ occasional depredations.

What worries Mr. Ansari are the anthropogenic pressures plaguing the region. The results of the Kosi River Corridor study recorded an alarming prevalence of humans and cattle in its camera-trap images, with Homo sapiens outnumbering that of any other creature. Given the way things stand, this is a problem the creatures of Mohan might simply have to learn to live with.

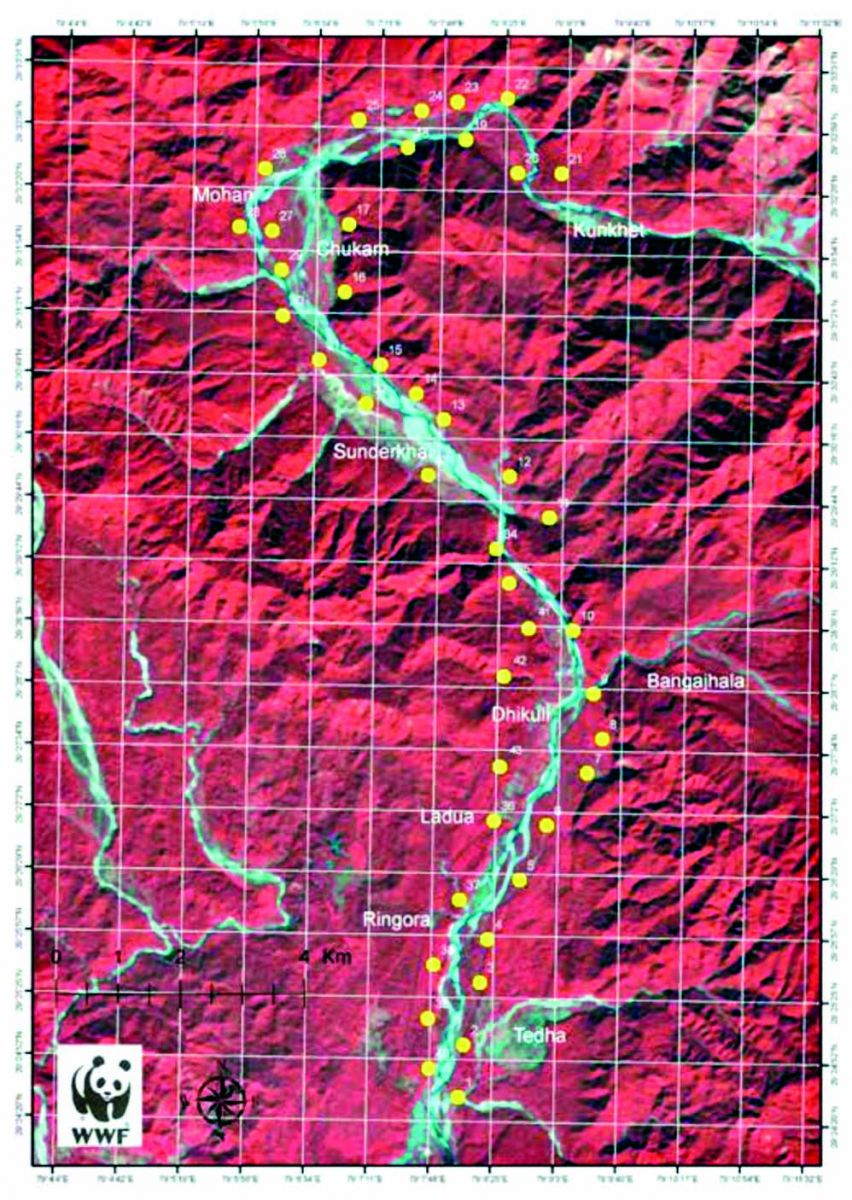

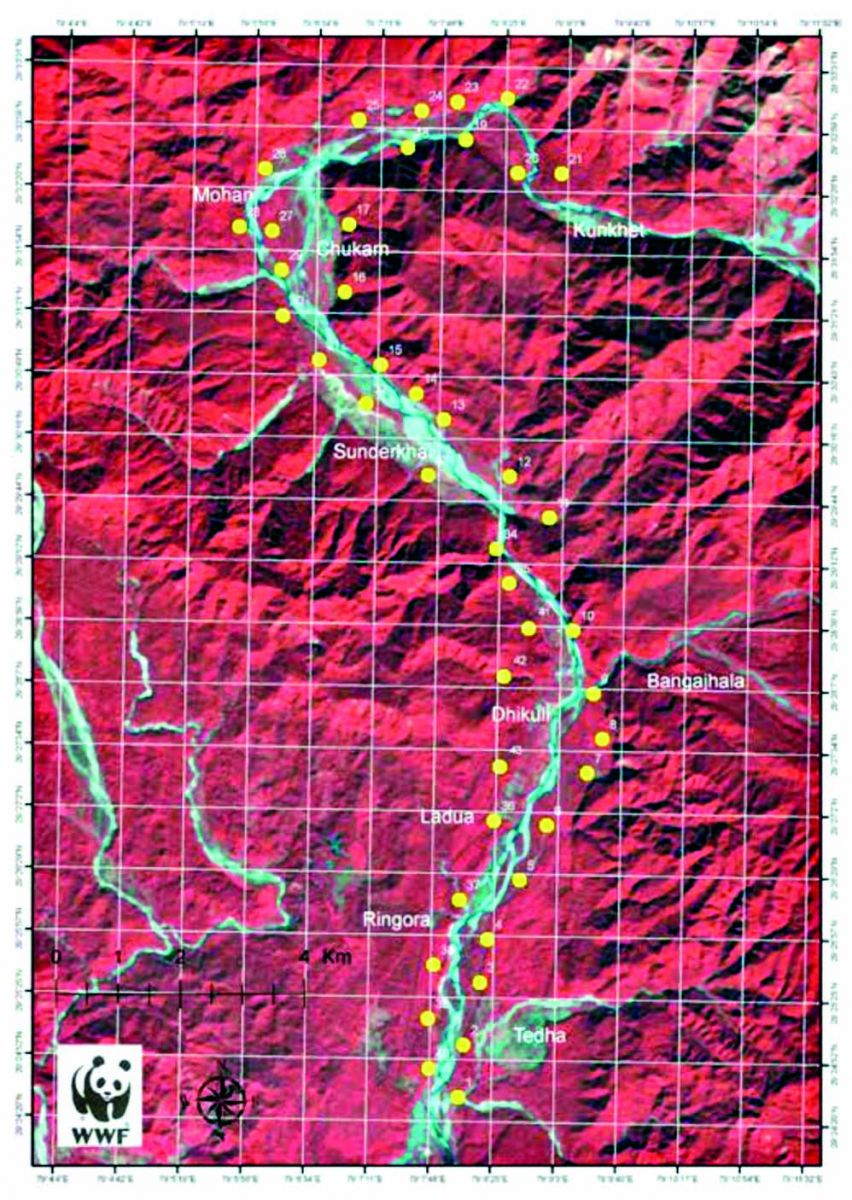

The Kosi River Corridor with strategically important points in yellow. This corridor is a crucial, contiguous belt of fringe habitat used as transit points for animals moving between the Corbett Tiger Reserve and the Ramnagar Forest Division. Source: WWF.

Etched clear in my mind is my most recent memory of Mohan. The sun had set and the stars shone bright in a moonless sky. A brooding silence hung heavy in the air. And as if on cue, a spate of poonks filled the gloomy void of quietude. Could those calls be of a feline on a hunt? I didn’t know, and I couldn’t have known. Yet somehow, I wasn’t bothered, for deep down I knew that as long as the chital belled, and the sambar bellowed, and the jumbos squealed, and the tiger roared, the magic of Mohan would keep luring me back for more.

Visitors are not allowed on foot in most Protected Areas in India. Sanctuary recommends that visitors unfamiliar with wilderness areas always be accompanied by experienced trackers or naturalists, especially while on foot.

A 25-year old talented freelance writer and photographer, Indranil Datta enjoys exploring the little-known regions of our better-known parks and jungles.

.jpg)