The Lure Of The Mountains

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 8

No. 10,

October 1988

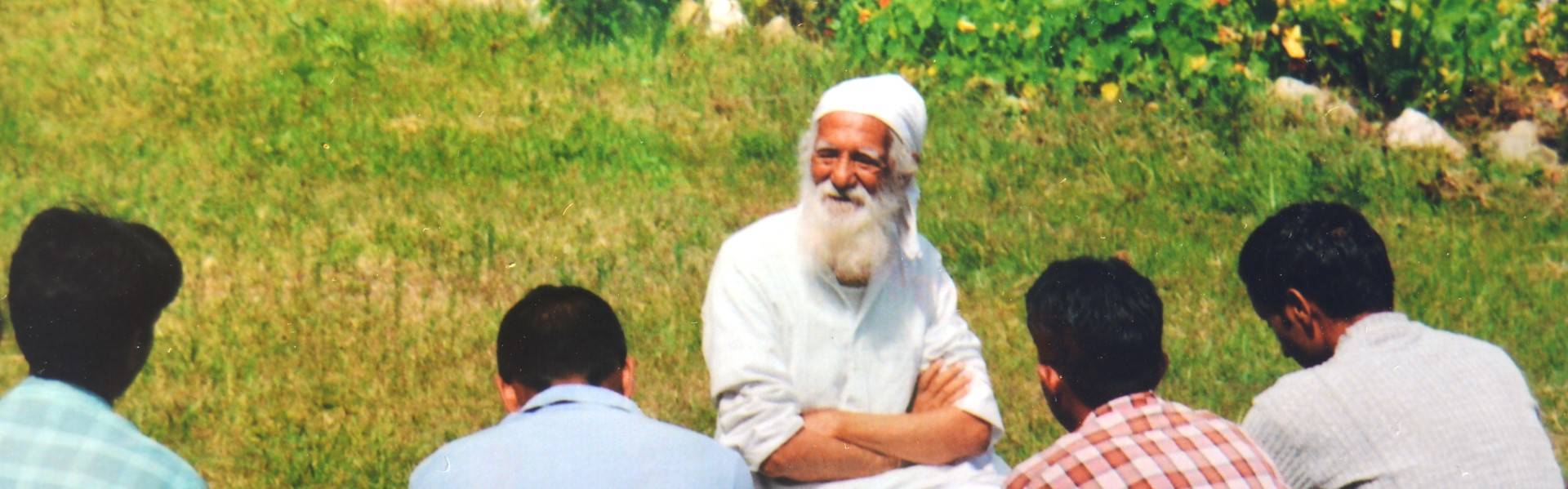

The world's greatest mountain range is being butchered. As forests and animals die, most people merely stand by and watch, horror-struck, but silent. But there are some whose voice rises to protect the Himalaya. Sunderlal Bahuguna, now recognised as one of the prime builders of India's new environmental awakening, has lived in the Himalaya throughout his life. Here he spearheads the famous Chipko Andolan and also fights to stop the Tehri Dam from destroying the mountains he loves so deeply. Some of his thoughts and experiences, culled from long foot marches, including a west-east marathon of 4,870 km. from Kashmir to Kohima, to spread the message of the Chipko Movement, are presented here. Despite the extreme provocation of callous, unresponsive planners, Bahuguna has continued to fight his battles in the manner of Gandhi, using persuasion and kindness in preference to bile and bitterness. His gentleness radiates from within him as he speaks, "I am growing old and cannot even carry my own back-pack now when I climb heights. Younger people must now come forward to save our land," he told Sanctuary. Yet, his eyes shine, and his manner is more youthful than the youngest among us. In an age of complexity and duplicity, Bahuguna's relevance extends way beyond the parameters of conservation, into the realm of humanity, peace and brotherhood.

The Himalaya has been an eternal source of inspiration to millions. The snowy peaks and glaciers, the dense forests, fast-flowing rivers and fertile valleys present an enchanting view of unparallelled scenic beauty. This great mountain range has a special message, not only for nature lovers, but to those seeking spiritual heights as well. The Bhagwad Gita, that great book of learning, for instance, quotes Lord Krishna as having said, "Among the steadfast, I am Himalaya."

Early settlers on the Indo-Gangetic plains, looked towards this great mountain as the source of their prosperity as its rivers irrigated their fields. For them, the Ganges and other rivers were not ordinary water channels, but a symbol of kindness, through which compassion flowed. For them, the river was a mother.

So began the pilgrimages to the sources of these rivers: Kailash, Mansarovar (now in Tibet), Amarnath, Gangotri, Yamunotri, Badrinath and Kedarnath. To this day, in spite of dangerous tracks, adverse climate and untold hardships, thousands still throng to these Himalayan havens to find themselves. In this modern world, however, contradictions are the order of the day. Mountains are also looked upon by some as objects to 'conquered'. Scaling high mountain peaks is regarded as high adventure, a feat of courage by our materialistic society. The construction of temples in the mountains by ancient people, however, had a more noble purpose -- one of total oneness with the elements, a form of true development which could be likened to a state in which the individual and society, achieved permanent peace, happiness and prosperity and ultimately fulfilment. To reach the heights of true development, one was taught to start with minimising one's material desires. Long trips to the places of pilgrimage in the mountains did not permit the carting along of luxuries. Thus mountains gave people a practical lesson in austerity. And by depending on fewer material possessions the individual was taught to scale the peaks of life and thus attain true and permanent development. This lesson of the mountains was obviously lost on many of the new travellers to the mountains who think nothing of cluttering the Himalaya with refuse and filth.

The objective, I expect, is more ego satisfaction than achievement and I sometimes smile inwardly at the bravado displayed by some of the `conquerors' of high Himalayan peaks. Saints and sages had been living in these areas with virtually nothing they could call their own for centuries. These ancients wore very few clothes, sometimes only a loincloth, and subsisted on locally grown herbs, tubers, roots and wild fruits. Some such souls can still be seen living in Gangotri (3,200 m.) and Gomukh (3,750 m.) throughout the year. Could such feats ever be emulated by the modern-day mountaineers, even with their goose-down quilts and all-weather tents, clothes and provisions transported on the backs of local porters and sherpas?

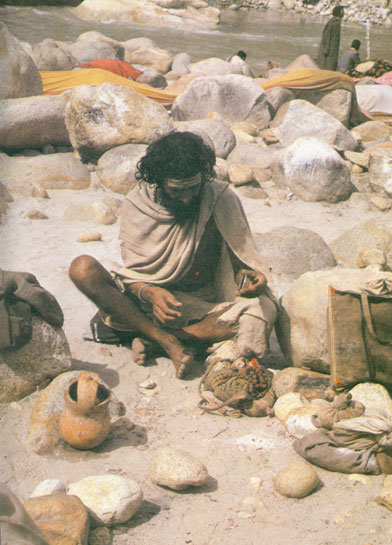

An ascetic takes stock of his meagre possessions while seated on the bank of a sandy glacial river. Unplanned exploitation by industry has taken away the vital timber resources which common hill folk depend on for their survival. Photo: Sunderlal Bahuguna.

Perhaps I am of a distant time. I cannot but feel sorrow at the fact that modern man has carried his ideas to the mountains. Motorable roads have been developed to reach new heights. The Himalaya, now has a snake-like network of such roads, zig-zagging from valleys to hill-tops, razing entire hill-sides and leaving landslips in their wake. The very mountains have been scarred.

Would that lessons from yesteryear could teach us something. In 1978 a 3 1/2 km. long landslide blocked the Ganges at Dabrani about 80 km. downstream from its source. Earlier in 1970, a similar catastrophe took place in the upper catchment of the Alaknanda, a tributary of the Ganges. Roads, built to 'develop' the mountains, actually accelerate soil erosion and landslides, caused largely due to deforestation. To make matters worse, inaccessible areas have now been opened up, providing abundant opportunity to commercial exploiters of timber to ply their nefarious trade. Such exploitation actually began in the mid-19th century when the British needed timber to build their railways. The plunder reached its climax during the Second World War and instead of abating, actually increased after Independence to meet the demands of the new 'rulers' who controlled industry, trade and commerce in the far away cities of the plains. The gifts of nature were intended for the consumption of all life forms. But modern man sees nature as a storehouse of raw materials for his need alone. Even this might not have been so bad if he had the good sense not to undermine the capacity of nature to deliver its bounty to us in perpetuity. Instead, to satisfy an overwhelming greed, in the name of progress, science and technology, a handful of people have devastated the Himalaya. Its green cloak now lies in tatters. After the forests, the hidden mineral wealth under the outer crust of the Earth began to be taken. This plunder has all but destroyed the accessible slopes and now, in the continuing quest for 'progress', even the valleys, which had thus far escaped because they were inaccessible, are to be drowned by new dams being planned across the ancient Himalayan rivers.

For a mountain which has breathed so much life into India, the Himalaya has been greatly mistreated. Deep wounds have been inflicted on it, wounds which may never heal, particularly in light of the fact that we still look upon the mountain as a commodity from which minerals, timber or electricity must be squeezed. Pahadis, true mountain dwellers, realise the benevolent nature of the Himalaya and in their hearts, they bleed with the Himalaya.

As a consequence of unchecked industrialisation, even the ascetics' simple demands for charcoal and fuelwood have begun to contribute to the degradation of Himalayan slopes. It is a tragedy that the people who hold the destiny of the great Himalaya in their hands are not from the mountains. They do not understand the spirit, nor the strength of this land. Yet they have the power to destroy the slender balance on which hinges the peace and prosperity of its simple people. Photo: Sunderlal Bahuguna.

The tourist who goes to these mountains in search of peace and happiness will never find such rewards if he takes with him his destructive way of living. He needs comforts and to provide him with these comforts, big multi-storeyed hotels have sprouted in small places, making fragile mountains all the more vulnerable to landslides. Sadly, now even some simple hillfolk, who lived in harmony with nature, have become agents of destruction, because the most profitable occupation for them now is to cut down trees for fire-wood and rear goats for meat. These can fetch a good price as the big hotels need these to cater to tourists. But no one cares to examine the price paid by the mountain in terms of deforestation and over-grazing. As a result, more silt is washed down through the rivers than ever before in the history of the Himalaya. Landslides, floods and other such miseries are the natural corollaries to such acts of foolishness.

We, in the Himalaya, had been silent spectators of this destruction. To begin with, it was development, but when the fury of floods, landslides and avalanches became acute, our very survival was threatened. This gave birth to the famous Chipko movement. Chipko means to hug. Trees are the sentinels of the Himalaya. Trees do not only increase the scenic beauty, but hold soil and water and deliver life-sustaining oxygen. To us, the mountains live. The Chipko movement has, therefore, challenged the short-term objectives of commercial forestry as being anti-people. If you ask the forest departments what the forests bear, they will reply, "Resin, timber and foreign exchange." If you ask a true pahadi what the forest bears, he will reply, "soil, water and pure air" - the absolute basics of life.

The Chipko movement filled the people with a new vision. For them, the Himalaya was a living being, a parent who reared them like children. When, as a result of the peoples' non-violent resistance against the rape of forests, a moratorium was put on the felling of green trees for commercial purposes in this region, we undertook a long march from Kashmir to Kohima across the Himalaya from west to east spreading the message of Chipko. During this march, we could see and feel the pain of the Himalaya. For us, this march was a means to share our anguish with the highlanders. This was a new experience, an experience to feel, rather than to think or to talk.

Women and men standing around trees, hugging them, holding each other’s hands -- this was the scene in a village in Uttar Pradesh in 1973, now in Uttarakhand, where the modern Chipko Movement took birth under the aegis of Sunderlal Bahuguna. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Several huge volumes on the Himalaya are published every year. Its problems are being discussed in seminars and meetings of intellectuals, but the Himalaya needs something else which the clinical mind cannot give; the Himalaya needs a compassionate heart to feel its suffering. It needs Earth healers, who by protecting its slopes and by planting trees can heal the wounds inflicted by landslides and soil erosion. And for this, the motto of mountain lovers should be "From our heads to our hearts with our hands."

Whatever we may individually think, let us feel and act collectively, with our hands, so as to return the timeless Himalaya to a measure of its former glory and strength.