The Kumbhalgarh National Park - Quintessential Rajasthan: Forts And Forests

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 4,

April 2022

The Kumbhalgarh National Park is located in the most rugged parts of the Pali, Udaipur and Rajsamand districts. Priya Singh, wildlife biologist who grew up a few miles west of this area, writes of her veracious explorations through the picturesque park during her study on the striped hyena.

Caressing the nooks and corners of the Aravallis is the Kumbhalgarh National Park within which is the Kumbhalgarh Fort. The fort, located on the park’s eastern boundary, was, according to legend, only defeated once in its history. Photo: Public Domain/Deep Goswami.

Denuded by forces of nature for millions of years, the Aravalli range is a striking topographical feature of northwest India. Over the last century, however, these hills have been brutally dissected and maimed by mining excavators and urban sprawls. This has paved the way for the growth of some of India’s most populous and modern industrial hubs such as Delhi, Gurgaon, Alwar and Jaipur. But the Aravalli is more than just a hill range. It is a landmass that provided safe lairs and vantage points to warring armies, it held back the Thar desert from crawling east, and it safeguards vestiges of north-western India’s biological wealth, much of which, today, is tucked away in small pockets of Protected Areas.

At the administrative juncture of two powerful erstwhile kingdoms, Mewar and Marwar, in south-central Rajasthan, within the Aravallis, lies a relatively little-known Protected Area, the Kumbhalgarh National Park. The park gets its name from the imposing fort of Kumbhalgarh located along its eastern boundary which, according to legend, was never defeated but for once. That this is a land of ancient battles is no secret. Cenotaphs dot the landscape as reminders of lives lost on the battlefield, while remains of fortresses such as Roopnagar and Desuri stand as proud evidence of a civilisation that was valourous and unbeaten. Less than 50 km. south-east of here lies the famous battlefield of Haldighati where, in 1576, an epic battle between Mewar and the Mughals was fought, and Maharana Pratap’s horse, Chetak, lost his life.

Caressing the nooks and corners of the Aravallis runs the administrative boundary of the Kumbhalgarh National Park, giving it a linear structure, around 60 km. long and five to 15 km. wide. With over 100 human settlements on its peripheries and upward of 20 settlements within the park, there is an obvious interaction between the communities living in and around Kumbhalgarh and those in the Protected Area. But the topography of Kumbhalgarh is treacherous, even for ancient warring armies. This means relict forests of the Aravalli are accessible only to the most determined.

I grew up in the semi-arid flats that lie to the west of Kumbhalgarh, just far enough for a faint glimpse of the hill range on clear days, or a glimpse of the ring of fire when the forests went up in a blaze during dry summer months. Stories of the Kumbhalgarh hills that I heard were the kind that fairy tales are made of. People spoke of the mighty rulers of Mewar who sought refuge in these hills in times of adversity; stories of Rana Kumbha’s lamp that lit up the night skies, and a land so fertile and water so plentiful that mango trees and date palm grew wild. Despite frequent visits to the foothills of the Himalaya for a primary education, the Aravallis of Kumbhalgarh remained the mightiest mountains with the densest forest in my young mind. Hence, when many years later, I was to identify a study site for my Master’s (in Wildlife Biology and Conservation) dissertation, Kumbhalgarh was an obvious choice.

Photo: Public Domain.

The Kumbhalgarh Fort

Photo: Public Domain.

The Kumbhalgarh Fort

The Kumbhalgarh fort is believed to have been built around the 6

th century. However, it attained its current form during the reign of Rana Kumbha (The early Mewar kings held the title of ‘Rana’ and later ‘Maharana’). There is no one single year when Kumbhalgarh was ‘built’ by Rana Kumbha. However, the 15

th century was when Kumbhalgarh gained much attention under his rule. Imposing in its grandeur, it served to shelter Udai Singh, father of Maharana Pratap, who was brought here from Chittorgarh by Panna Dhai. Later, Maharana Pratap used the fortress effectively in the battles against the Mughal Emperor Akbar. In 2013, Kumbhalgarh, along with five other hill forts of Rajasthan (which includes the Ranthambhore Fort), were included as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Re-discovering Kumbhalgarh

One of my study objectives was to estimate hyena densities in Kumbhalgarh, and compare them with those from a non-protected site within the same landscape. I was being guided by Dr. Ullas Karanth, a leading authority on estimating carnivore populations using a combination of statistical models, and photographs of uniquely marked species, obtained from remotely triggered camera traps. This was 2007, an era that preceded the age of digital camera traps. Bearing in mind my study sites were in a human-dominated landscape, and the challenges of protecting camera traps in such areas, I was allocated the cheapest camera traps that my funding organisations could spare. My advisers had adequate experience to predict camera trap loss rates in Protected Areas with high human presence. I, of course, was yet to develop such knowledge.

The camera traps used 35 mm. film rolls with 36 photo frames each, had no automated mechanism to print date and time on photos, required eight AA alkaline batteries to power them, and easily qualified as unpredictable in their behaviour. If the cameras were challenging, my study species, the striped hyena, was even more so. It took several months of hard work and persistence to develop mechanisms to negotiate technical, logistical and ecological challenges. The end result of several months of back-breaking work was a study that identified a high prevalence of the striped hyena in Kumbhalgarh, and its advantageous relationship with undulating topography that provided it safe denning refugia. It was a relatively simple study, but for its time, novel and enlightening. Additionally, it brought attention to the hyena, which had until then been highly neglected.

A common leopard, apex predator in the park, and a striped hyena. The author’s study identified a high prevalence of the striped hyena in Kumbhalgarh, and its advantageous relationship with the undulating topography that provides it safe denning areas. Photo: Iyer Raghu.

Having stringent advisers meant that I was constantly being tested. In January 2008, my co-adviser, Arjun Gopalaswamy, joined me for a field visit. While training me on identifying suitable camera trap locations, he decided I needed to cross over into the adjoining valley. This meant one of the two options… use an existing network of trails and roads and drive to the area, or walk a straight transect through the unknown and hope to reach the destination before sunset. Expectedly, I was instructed to follow the latter option. This transect, a first for me in this landscape, opened my eyes to a Kumbhalgarh that one rarely sees. The walk started with negotiating Dendrocalamus strictus brakes, proceeded into a dense, dry patch of Heteropogon grass, and finally led us to a beautiful wild animal trail. As the trail approached the summit of the hill, we flushed out three sambar. Dusk was just setting in, and our ascent to the hill synchronised with the lighting of Kumbhalgarh Fort, located at a straight distance of 10 km. The majestic fort, with its 36 km. long rampart, towers over the National Park and is visible from many parts of the reserve; however, this view was extraordinary.

A common leopard, apex predator in the park, and a striped hyena. The author’s study identified a high prevalence of the striped hyena in Kumbhalgarh, and its advantageous relationship with the undulating topography that provides it safe denning areas. Photo: Public Domain/M.V. Shreeram.

Beyond hyenas

Over the next few months, I walked many such trails. One day, walking by myself, several kilometres from Kharni Takri settlement, I came across a male chousingha. Not expecting any humans and unaware of my presence, it allowed me adequate time to gaze at its unique horns and then froze on noticing me before fleeing. One of the most feared animals in Kumbhalgarh is the sloth bear. On one occasion, after much persuasion, I had managed to get a local person to accompany us to a tall grassland, a habitat commonly avoided by the locals for fear of bears. We didn’t just startle a bear, but a mother bear with a tiny cub! In the same location, we then almost walked into two extraordinarily big Russel’s vipers. Meanwhile, my camera traps photographed langurs, nilgai, wild pigs and feral cattle regularly. Hyenas and sloth bear were infrequent, and leopards rare.

In the 1990s, Kumbhalgarh became a popular destination for sighting the Indian wolf. On the western side of the park, an area called Joba was developed specifically for wolves. A waterhole was constructed, and a peep hole dug out some feet away, which allowed for wolf-watching. A guard was assigned to regularly replenish the waterhole with fresh water, and maintain records of wolves that visited it. For some time, this worked as a great mechanism to watch and photograph wolves, with the Joba pack becoming one of the most photographed wolf packs of its time. By 2008, this arrangement was long discontinued, but the waterhole remained, and I could witness remnants of it. During my stay in the area, I desperately longed to see wolves. The closest I got to seeing them was on a hot day of March 2008, when a small pack visited a waterhole near the Sumer guest house. The western plains of Kumbhalgarh are dominated by a pastoral community, the Raika. With a substantial part of their livestock being sheep and goat, when a wolf is in the area, Raika are quick to notice and take action. My local guide, adviser and friend, Ratno ba, also from the Raika community, came running to inform me just few minutes too late. I missed seeing the pack.

Caressing the nooks and corners of the Aravallis is the Kumbhalgarh National Park within which is the Kumbhalgarh Fort. The fort, located on the park’s eastern boundary, was, according to legend, only defeated once in its history. Photo: Public Domain/Ashvij Narayanan.

Thriving against Odds

A decade hence, when I look back at my time in Kumbhalgarh, I am amazed at the life this small linear region supported. Surrounded by a mass of humanity; dissected by two major public roads (Desuri ki Naal SH 16 and Saira-Ranakpur SH 32); hosting pilgrim traffic from prominent religious sites such as the Ranakpur Jain Temple and Parshuram Mahadev to name a few, and housing pastoral and forest dependent communities, it’s a miracle that this patch of forest survives. This is especially significant when I compare it to my current study sites in Northeast India, where months spent working in large forested landmasses could yield no mammal sightings. Not only is Kumbhalgarh important from a biodiversity perspective, but despite its location in a low rainfall region, this forest is a source of water to myriad small rivers such as Sumer, Sukri, Kot, Jawai and Sei. Even in summer months, when parts of Kumbhalgarh burn due to accidental fire or because of magra snan (literally translates to ‘bathing the hills’), a custom practiced by the local Garasiya community to appease spirits of the forest, pools of water shaded by Syzygium trees survive.

Mahua – Madhuca sp. is abundantly found around Kumbhalgarh and its flowers and fruits are consumed by both humans and wild animals, especially bears. Palash trees also provide nectar for many bees, butterflies and other insects that, in turn, are foraged by birds! Photo: Public Domain/Kandukuru Nagarjun.

Over the last couple of years, a select few politicians and conservationists have aggressively pushed for declaration of Kumbhalgarh, along with a contiguous Protected Area to the north, Todgarh-Raoli, to be jointly declared as a tiger reserve.

The Banas river

The Banas river

In an arid landscape, water is naturally the pivot around which all life revolves. The life-giving monsoons usually arrive in the last week of June and continue all the way to September, with occasional rains in winter. The hills are the watershed between the low-lying desert plains to the west and the high plateau of the Udaipur region to the east. The undulating terrain drains the forest efficiently. From the heights of Rana Kankar, at an altitude of 1,400 m., one can see stream beds joining the Lilri and Sukri rivers in the west. These rivers then flow on to meet the famous desert river Luni and, ultimately, the Arabian Sea. The streams to the east of Rana Kankar flow into the Banas river and then to the Bay of Bengal.

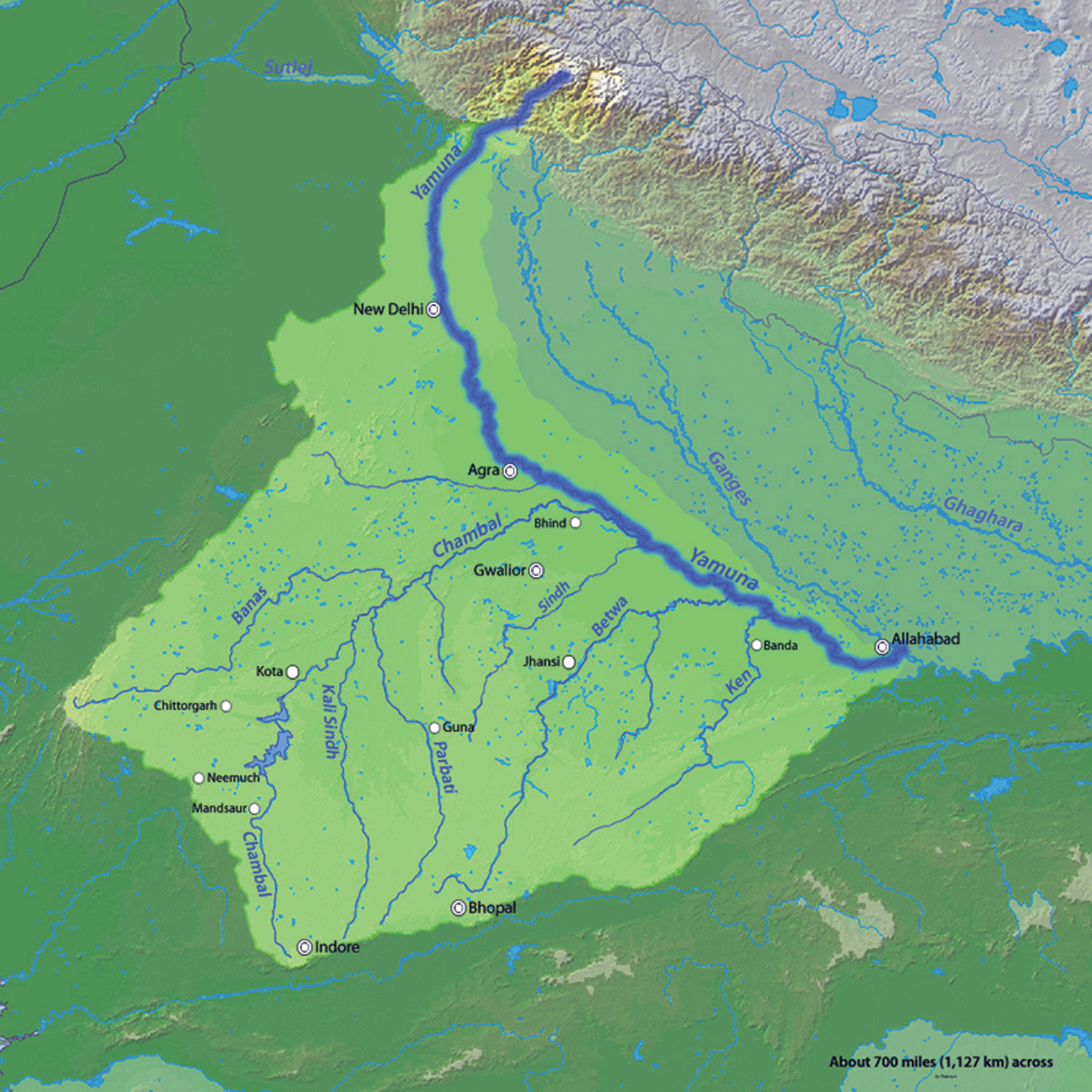

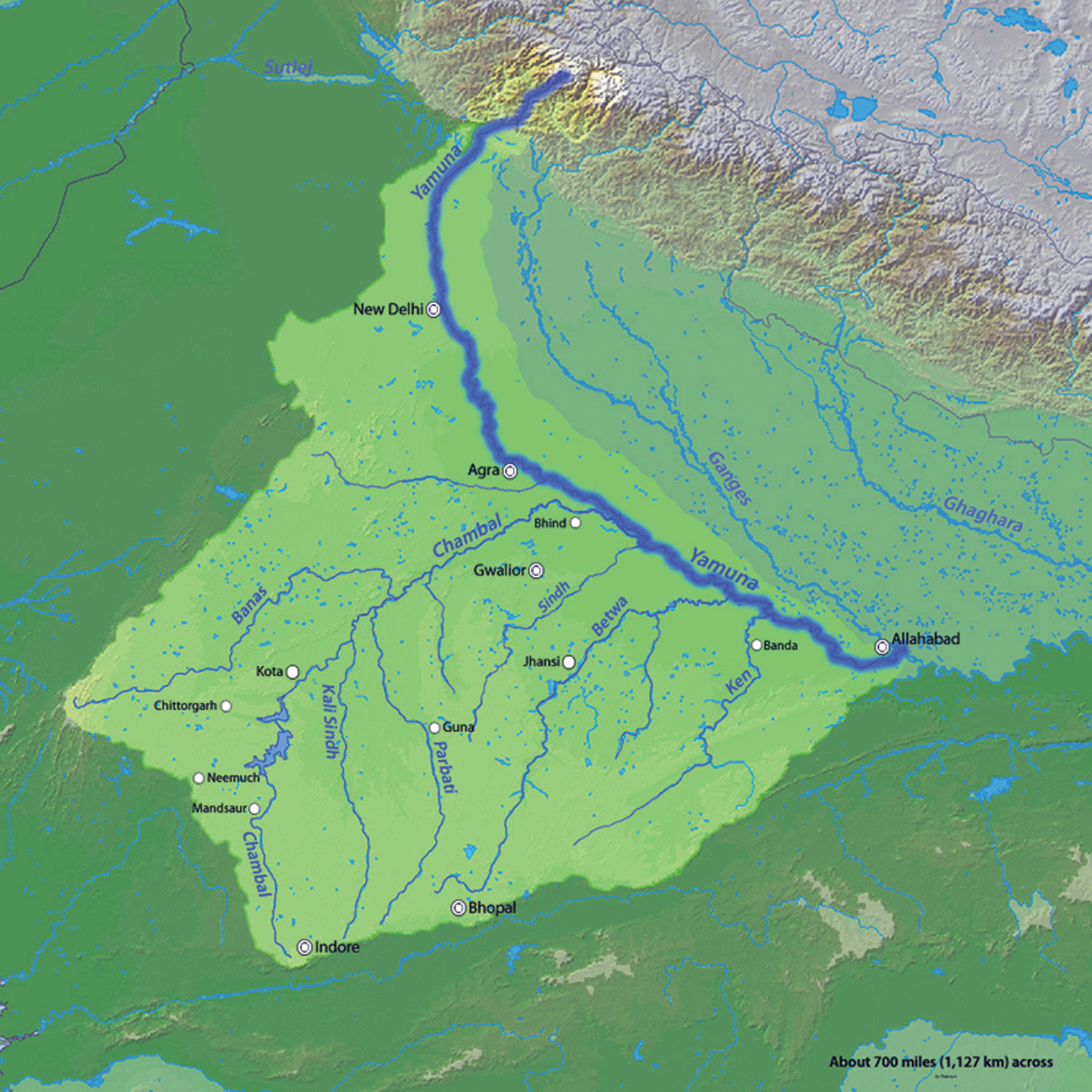

The Banas river originates from the hills near the Kumbhalgarh fort. After flowing through the outlying edges of the Aravallis, it runs through the Gogunda plateau and bursts into open country. It meets the Chambal, the main tributary of the Yamuna, at Rameshwaram near the Ranthambhore National Park and ultimately joins the Ganges. Berach, the main tributary of the Banas, also originates from this area. Ahar-ki-nal near Gogunda is the birthplace of Berach. This river flows southeast and joins the Banas in the Bhilwara district, more than 300 km. away. The Wakal river also rises near Gogunda and eventually joins the Sabarmati river.

By K. Rajpal Singh, Published in Sanctuary Asia, February 2002At first glance, the reasons for their enthusiasm appear reasonable – historical evidence of tigers in this landscape and hence restocking the area with the now locally extinct predator while simultaneously creating an alternate home for surplus tigers from Ranthambhore. However, a myriad socio-ecological reasons make others sceptical of this plan, while questioning if the same monetary resources could give greater returns elsewhere where natural forest connectivity currently exists with tiger source habitats.

Mahua – Madhuca sp. is abundantly found around Kumbhalgarh and its flowers and fruits are consumed by both humans and wild animals, especially bears. Palash trees also provide nectar for many bees, butterflies and other insects that, in turn, are foraged by birds! Photo: Public Domain/Siddarth Macchado.

The Kumbhalgarh landscape is culturally so diverse, and yet so quintessentially Rajasthan. During the period of my field work, I would often move between the plains in the west and the elevated highland to the east. The cultural, ecological and topographical variations were striking. As one moved from the west to east, within a span of 10 to 15 km., the vegetation, composition of local communities, dialects, dominant livelihoods, and customs all seemed so different, and yet, were overarchingly Rajasthani.

In a striking way, this is the heart of Rajasthan, where two powerful dynasties, the Ranbanka Rathores of Marwar and the Hinduva Suraj of Mewar meet; where the desert sands of the far west meet the fertile lands of the east. It is the place where the Aravallis still wear a green cloak, and provide refuge to biodiversity that has lived here for eons.