The Forgotten Tigers of Pilibhit

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 24

No. 6,

June 2004

By Ramesh K. Pandey, IFS

The small herd of 16 swamp deer grazed peacefully along the swampy banks of the Mala river as I watched them from behind forest cover. How I wished I could wave a magic wand and double the numbers of this endangered species! That they still survived here in the Pilibhit Forest Division, Uttar Pradesh, together with tigers, the occasional elephant and many other mammals, was a minor miracle. Pilibhit is a non-Protected Area (PA), but a history of protection, coupled with the area’s natural isolation, makes this one of the non-PA areas with the highest wildlife potential.

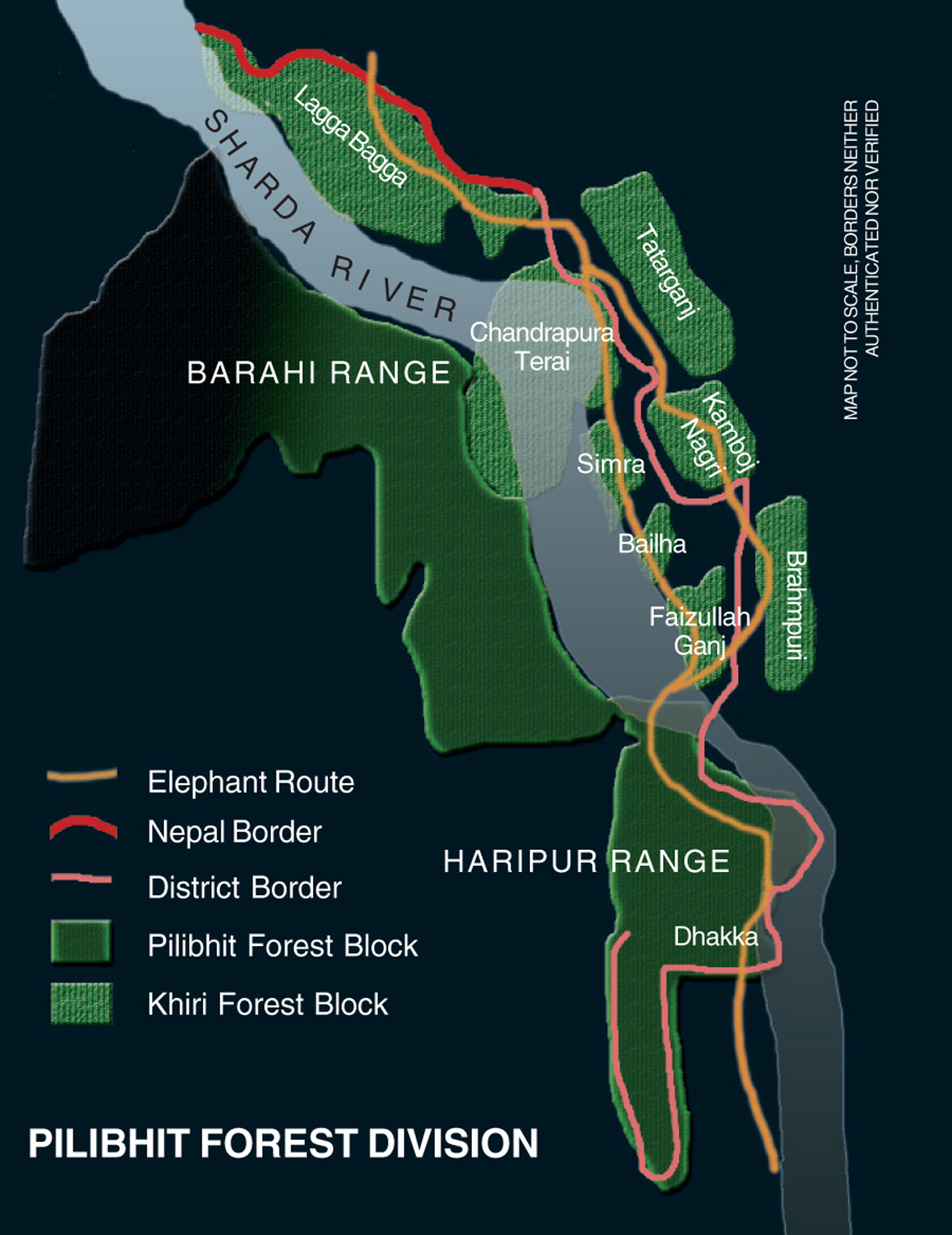

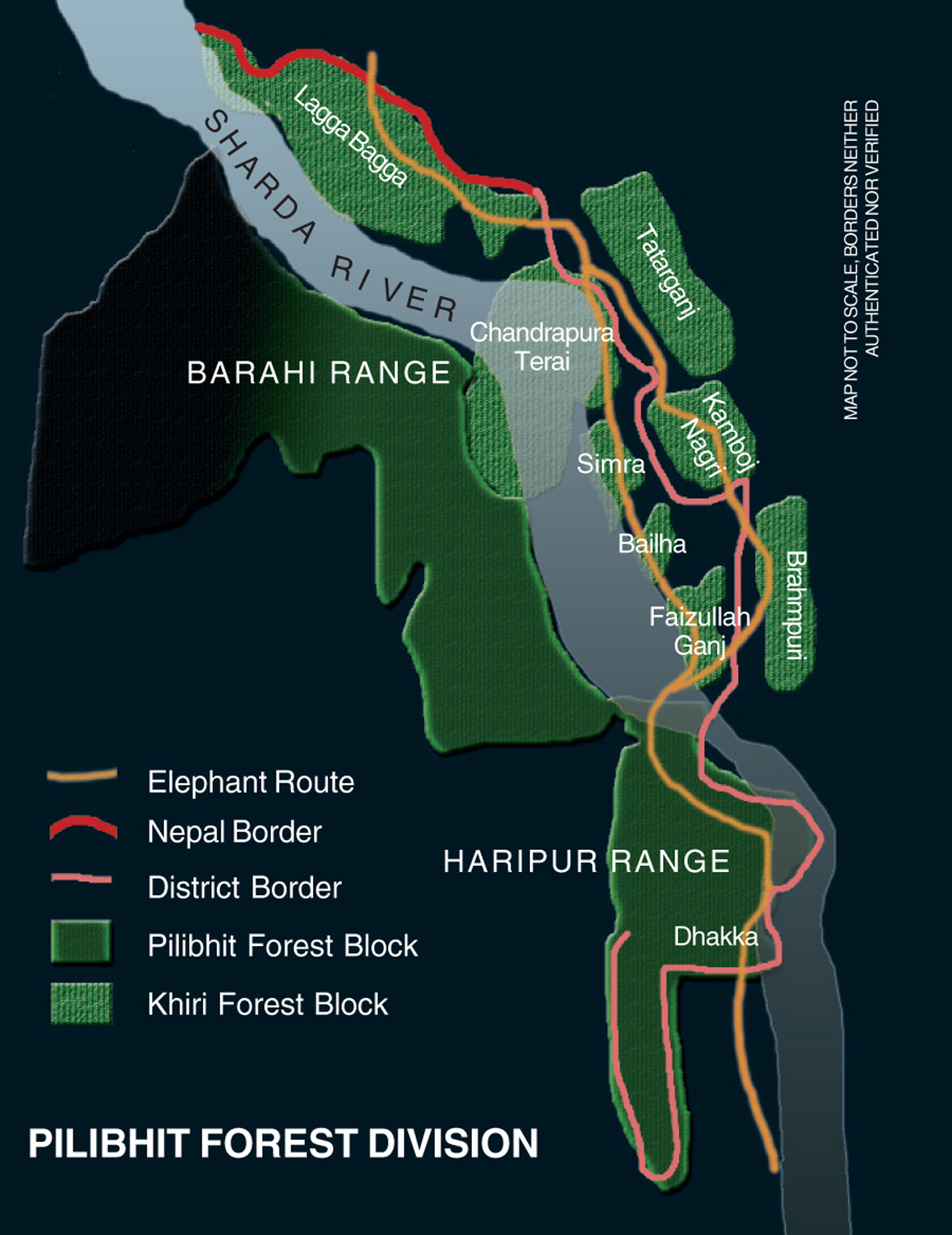

The 750 sq. km. Pilibhit division is one of the richest in the Indian terai. A compact forest patch, largely unbroken by habitation, its importance goes far beyond its significant size. It is linked by functional corridors to the Royal Suklaphanta Wildlife Reserve in Nepal to the west and the Kishanpur Sanctuary to the east, providing a large, relatively contiguous forest terrain. The Pilibhit block is about 90 km. long, varying in width from five to 15 km. This is largely reserved forest, notified before Independence. The Sharda river and its tributaries water most of the forest block.

I have spent many wonderful misty mornings in these dense sal forests, tracking chital or following the pugmarks of a tiger. Though sal is the dominant species, asna, jamun, kusum, harra, bahera and rohini are also found here. The forest is interspersed with tall wet grasslands, perfect for ungulates. The swampy areas near the Mala and Sharda rivers support a decent population of the highly endangered swamp deer.

Pilibhit’s richness can be gauged by the presence of the terai’s three major charismatic species: tigers, rhinos and elephants. While rhinos and elephants are not permanent residents, they do spend significant periods in the Lagga Bagga area of Pilibhit. The 2003 census recorded the presence of over 30 tigers, with a male-female ratio of 12:16, plus four cubs. Additionally, over 400 species of resident and migratory birds make Pilibhit a birding paradise.

The conservation community needs to take account of this viable tiger population, which could grow since these forests are relatively undisturbed and chital, sambar, hog deer, barking deer, swamp deer and nilgai are easily available. I have also seen sloth bear here and the rare hispid hare has been recorded in Lagga Bagga.

Photo:N.C. Dhingra

Tourism as conservation

With a view to harnessing the potential benefits of tourism, an ecotourism location has been identified in the Mahof range, which has a high ungulate density and a decent tiger presence. Situated on the northern banks of the Sharda Sagar reservoir, the location is known as the ‘Chuka beach’. Here, four huts, a common gathering place and a ‘machan’ – all built with indigenous materials and ethnic know-how – provide basic facilities. More than 3,000 tourists have visited the complex since its inception, and the local community, whose participation has been a key feature, earned over Rs. 25,000 in the last tourist season. This is the first such instance of wildlife ecotourism in a non-PA forest and I believe it has proved its worth, bringing people closer to nature and helping spread the message of conservation.

Where elephants roam

The Lagga-Bagga area’s tall wet grasslands and swampy patches attract elephants and rhinos, as well as swamp deer, hispid hare and the rare Bengal Florican, the latter two only recently reported. Classified as a ‘Type Two’ grassland, it supports over 200 resident and migratory bird species. It is linked to both the Suklaphanta and Kishanpur Sanctuaries and is therefore of crucial wildlife significance. The Suklaphanta-Lagga Bagga-Kishanpur corridor is probably one of the most important ones in the Indian terai for elephants. There have been numerous reports of scattered and small groups moving through the forest. The largest elephant herd recorded here numbered about 25 individuals, in 1996. The same year, three elephants were also recorded at the Dhakka forests of Haripur range. Elephants have also been known to directly enter the Tatarganj forest of North Kheri division from across the border, crossing the Sharda and then moving through the Barahi-Haripur ranges of Pilibhit. If wildlife is of importance to us in India, we should help protect this key elephant corridor. The benefits to Pilibhit’s farmers in terms of improved water regimes alone would be a great ‘pay back’ from nature.

And the good news is…

The Forest Department has been doing its bit to protect Pilibhit’s wildernesses with limited resources. But effective conservation action demands more. When WWF-India stepped forward to provide infrastructure support in the form of an elephant, jeep, motorcycles, wireless sets, a boat and camping gear, a step was taken in the right direction. With the help of local communities, a patrol camp is being set up in Lagga-Bagga, to boost the forest department’s patrolling capabilities. WWF has also organised awareness programmes, ‘nukkad-nataks’, film shows and other events for local communities and field staff. Health camps and educational programmes in villages such as Gabhia Sahrai, Naujalia, Ramnagara and Mahrajpur are slowly helping to communicate positive messages about conservation, which should translate into changed attitudes among locals.

From across India, we hear dismal tales of wildlife in retreat. In the case of the Pilibhit Forest Division, we have one of the few Indian examples of wildlife actually being protected outside the sanctuary and national park network. If other wildlife-rich reserved forests, especially those that are crucial wildlife corridors, were to follow the simple measures taken recently in Pilibhit, India’s threatened wildlife would reap a biodiversity whirlwind. It is time for some of the attention lavished on our most famous Protected Areas to be diverted to the larger, largely forgotten, territorial forest areas that hold the real key to the continued survival of India’s wildlife, especially larger species such as tigers and elephants. However, I do not by any measure wish to suggest that everything is perfect (see box) in Pilibhit… just that this incredible forest area gives us reason to hope.

Pilibhit, the unfinished agenda

1. Corridors between Pilibhit and other wildlife areas need focussed conservation.

2. We need to consider reintroducing rhinos to the Mahof and Mala ranges.

3. The stagnant swamp deer population should be raised with sensible habitat management strategies.

4. Pilibhit’s ecotourism model should be studied, improved and then possibly replicated elsewhere in India.

5. Local communities’ dependence on forest biomass needs to be kept at sustainable levels.

6. Wildlife training and capacity building programmes must be provided to staff.

7. Good field research is required to help us better understand population dynamics and habitat requirements for wildlife.

8. Cross-border (Indo-Nepal / Uttar Pradesh-Uttaranchal) information sharing and communication is very poor. Suitable protocols and regular meetings and data sharing workshops involving local communities and NGOs are needed.