The Ecological Cost of Increasing Infrastructure in Forests

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 8,

August 2020

By Nicole Pinto

Linear infrastructure, such as roads and railway lines, which cut through wildernesses act as barriers to the movement of animals, increase roadkills and human-animal conflict, and facilitate the spread of diseases from animals to humans. It also promotes the growth of non-native plant species along its boundaries.

A recent study found the density of linear infrastructure in Protected Areas in India (such as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries) to be similar to that of non-protected forested areas. Moreover, 70 per cent of the Protected Areas analysed had linear infrastructure passing through them, suggesting the need for better planning and scrutiny of projects passing through them.

This study comes amid proposals for projects such as the Hubbali-Ankola railway line, 80 per cent of which will pass through the Western Ghats, a global biodiversity hotspot, and the 3,097 MW Etalin Hydroelectric Project, that requires the diversion of 1,150 ha. of forestland.

While hydroelectric and mining projects are not categorised as linear infrastructure, they require roads and other supporting infrastructure that increases the ecological impacts of these projects. Clearances for this supporting infrastructure are often sought in separate applications, making it hard for regulators to reject them due to the vast resources invested in the main project.

Since July 15, 2014, there have been nearly 19,000 proposals to use about 3.8 lakh ha. of forest land for non-forestry purposes. Linear infrastructure projects make up about 67 per cent of the pending forest clearances applications, but seek to divert only about 20 per cent of the 3.8 lakh hectares requested, according to Srinivas Vaidyanathan, a senior researcher at the Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning.

“This highlights the current threat that linear infrastructure projects pose, which is often ignored as they seek relatively small amounts of forest land to be diverted, and their negative impacts are neglected while giving clearances,” he says.

Large forest patches, which are integral to maintaining a diverse and genetically viable population of animals, are most vulnerable to being fragmented by infrastructure. There has been a 71.5 per cent reduction in the number of large forest patches in India. The researchers only considered national highways, state highways, and district roads in their study, and found major roads and high-tension power-transmission lines to be the most abundant form of linear infrastructure in forests.

A National Highway passing through a forest patch in the southern Western Ghats. Photo: Srinivas Vaidyanathan.

India has the second-largest network of roads in the world, and aims to add 34,800 km. of National Highways between 2017 and 2022, according to a report by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highway. The ecological implications of such initiatives need to be considered, and to this end, this study examined forests in two conservation priority landscapes - Central India and the Western Ghats.

The researchers found that forests covered 35 per cent of Central India, yet only 11.34 per cent of these forests were protected; while in the Western Ghats, 68 per cent was covered by forests, of which 25 per cent were protected.

Their analysis also showed that Central India had a higher number of large forest patches as compared to the Western Ghats, but there was low connectivity between patches. In the Western Ghats, the forest patches were relatively smaller in size, but they were located closer to each other and thus had greater connectivity.

A separate study, co-authored by some of the same researchers, found natural areas occupied only between 50 - 70 per cent of areas that posed relatively low resistance to the movement of large mammals in Central India, and between 20 - 60 per cent in the Western Ghats. The authors considered natural areas as forest, scrubland, grassland and barren land for the study.

The study, the first in India to look at multi-species movement across an entire landscape, found reduced movement of five wide-ranging mammals (elephant, gaur, leopard, sambar and sloth bear) in the Western Ghats and four (gaur, leopard, sambar and sloth bear) in Central India, primarily due to infrastructure, human habitations and different human land use types (such as agriculture, reservoirs, built-up areas). These results suggest that a large portion of areas critical for the movement of wild animals are not completely permeable as they occur outside natural areas where conservation planning is often neglected.

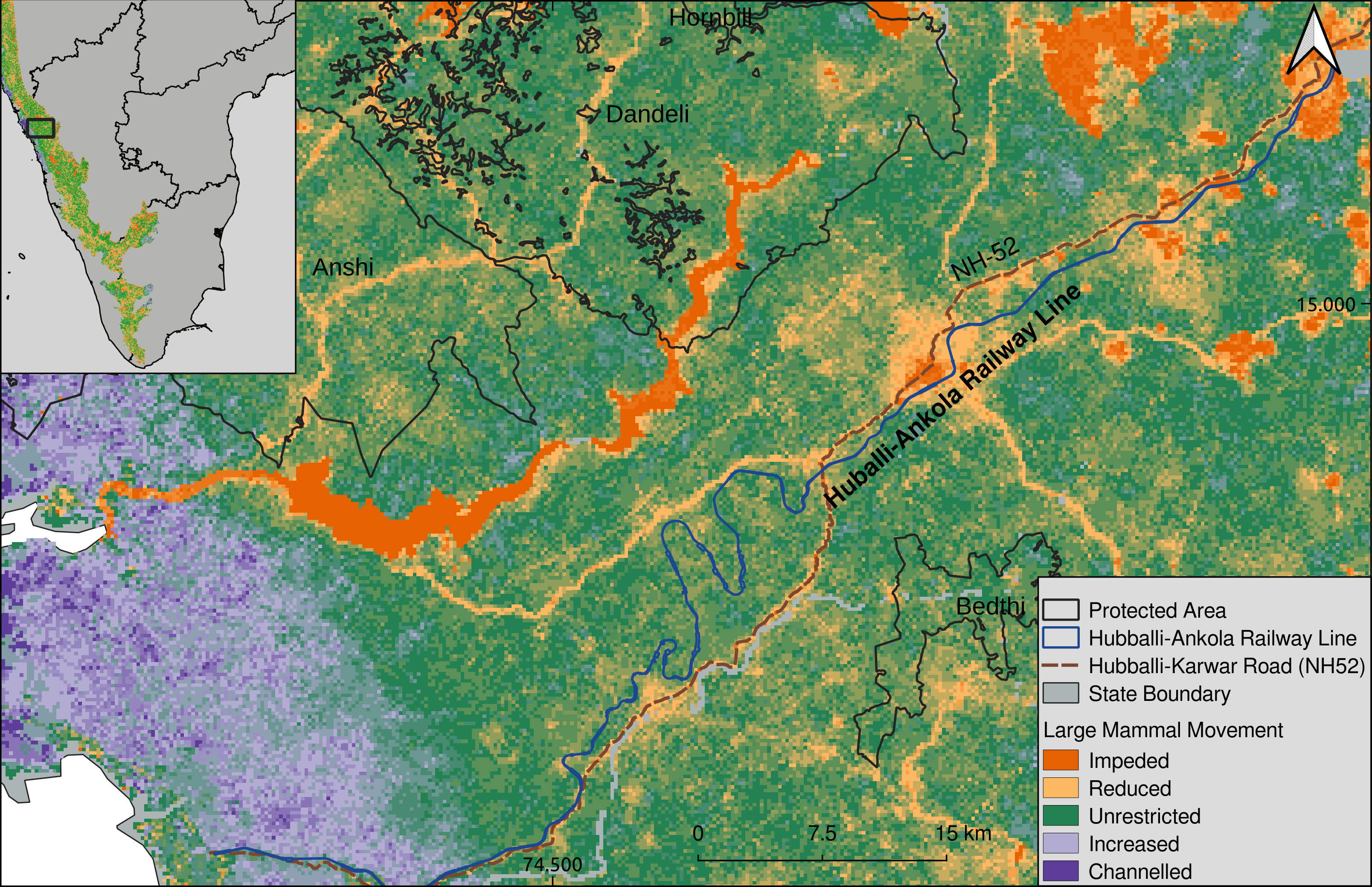

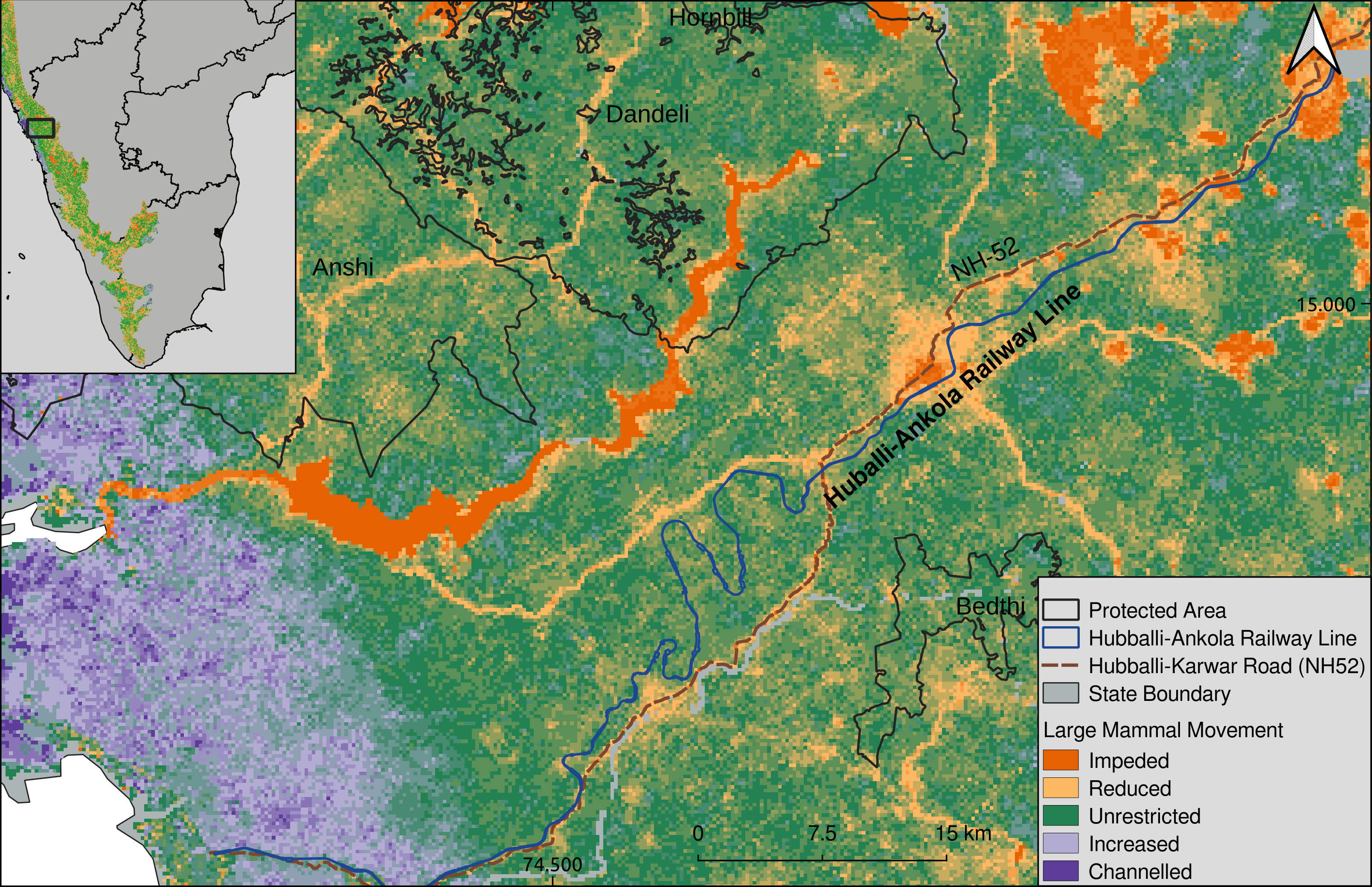

The earlier mentioned Huballi-Ankola railway line, which is under an interim stay order, will cut through 10 large forest patches in the Western Ghats if cleared. It will split these into 15 smaller patches, some of which may be too small to sustain the existing biodiversity in the long run. The proposed railway line will also pass through areas where movement of elephants, gaurs, leopards, sloth bears and sambar have already been reduced, and will only further increase fragmentation and hinder movement. The proposed railway line runs alongside the Huballi-Karwar road (NH52) and will thus pose an additional hindrance to animal movement, according to Rajat Nayak and Anisha Jayadevan, the lead authors of both papers.

The project officially estimated felling of between 1.78 lakh to 2.2 lakh trees, a figure that experts believe has been grossly underestimated given the high canopy density in the area.

Map showing the proposed Huballi-Ankola railway line and movement of large mammals in the Western Ghats. Map courtesy: Anisha Jayadevan.

Researchers from both studies stress the need to reconcile development goals with that of conservation, and by providing data on existing forest patches and movement patterns of animals, these studies serve as a guide to decide “where” and “how” future development activities can be undertaken. They also recommend that site-specific mitigation measures be employed to reduce the impact of these projects on the movement of animals.

Linear infrastructure projects within forests, especially large forest patches, should be avoided. When it is unavoidable they should be rerouted, bundled, or include effective mitigation strategies, according to the results of the study that analysed forest fragmentation due to linear infrastructure.

The impact of development projects should be assessed across the entire landscape and not just within or between Protected Areas. Caution should also be taken while choosing species to represent movement patterns as the impact of infrastructure, human habitation and human land use are not uniform across species.

Additionally, areas critical to the movement of animals and large forest patches should be conserved and further land use change should be prevented. This includes natural areas and places where movement is channelled and where even a small reduction in area can severely hinder connectivity.

An open-access interactive map depicting forest patches and movement patterns of animals can be found at this link. This information can be used to identify and prioritise areas where restoration, mitigation measures or infrastructure realignment should be planned.

Nicole Pinto started out as a correspondent writing about financial markets but now works for the Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning to communicate stories about the natural world. She also works as a research assistant on the Frontier Elephant Programme that aims to help farmers find proactive approaches to mitigate conflict.