The Dolphins Of Malabar Hill

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 6,

June 2023

Text and images by Darshan Khatau

I stared out at the sea and spotted a pod of playful Indian Ocean humpback dolphins Sousa plumbea. I focused my binoculars on a mother with a young calf, then moved to watch in amazement as I saw a courting couple. I was not sailing on distant shores in some exotic location, I was standing where I stand every day, in my sea-facing home in Malabar Hill, Mumbai!

Unknown to the vast majority of our citizens, such marine magic is still visible to those interested enough to take the time to ‘stand and stare’ at key locations along Mumbai’s exquisite seascape, which is, in my view, far better than that of scores of more celebrated seaside cities across the globe.

Dolphins leap out of water for a number of reasons – to get a bird’s eye view of their surrounding, to communicate with their pod and also to conserve energy while swimming long distances.

As I continued watching them dive and gambol about over the next hour, my heart lifted and, for a while, the angst that the city democratically feeds us daily, vanished. I am blessed to share my home with the largest urban forest that survives, outside of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, between the campuses of the Raj Bhavan and the Parsi Panchayat land that have mercifully been kept out of the reach of the construction sector.

I often wonder why humans have drifted so far from nature and why people seem so apathetic towards the degradation of the biosphere upon which their own lives are fully dependent. At some point, way before the Portuguese arrived, dolphins and whales must have roamed this very coastal stretch in large numbers. Though I am grateful for every tiny sighting, the dolphin pods visible today are scattered in small pockets, including the ones that visit the Chowpatty bay, off the Raj Bhavan, in Malabar Hill.

When Your Backyard Is The Sea

I have been documenting the movements of the Indian Ocean humpback for over four years now, but recall my paternal uncles, Jaymal and Mahendra, speaking about sightings for over two decades. My dolphin vigil was well and truly sparked during the COVID-19 pandemic when the lockdown enabled me to document their presence and behaviour with enough time on hand. Some of the videos I shot and uploaded on social media went viral, and others too began to confirm sightings off Mumbai’s coast, largely between the months of December until the onset of the monsoon.

Studies by the Central Marine Fisheries Research (CMFR) Institute have also shown that the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin can survive in and adapt to polluted coastal waters, and are not easily disturbed by large vessels or noise pollution. CMFR is yet to understand the levels of disturbance the species can tolerate.

The dolphins use this space to forage and socialise and I have seen pods cooperatively foraging and chasing schools of fish, just under the water’s surface. I have also observed an adult and calf foraging together, some mating chases, and their acrobatic breachings involving ‘spy’ hopping and porpoising! Their cooperative foraging involves chasing schools of fish towards the shore and then hunting the fish down by trapping them in the shallows against the Chowpatty sands.

Initially, sightings of even two or three individuals would be a cause for celebration, but more recently I have noticed pod sizes of between five to seven, with occasional sightings of calves.

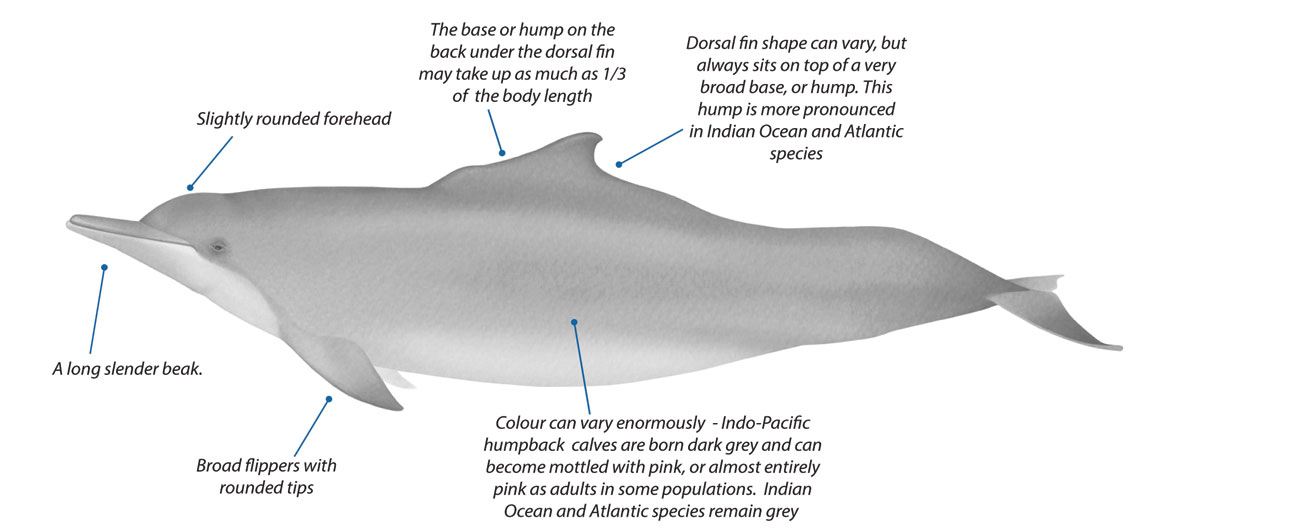

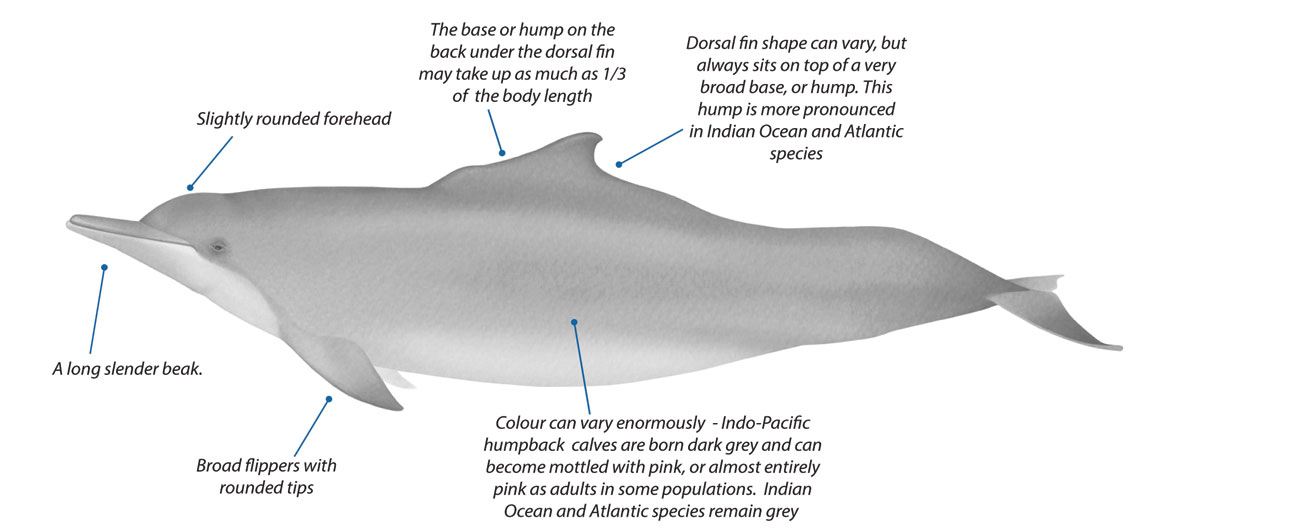

Photo: Public Domain.

Indian Ocean humpback dolphins are social delphinids and in cleaner, more productive waters, can be seen in groups averaging around 12 individuals. Group sizes, of course, are highly variable, depending on the abundance of favoured foods such as sciaenid fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans.

Dr. Dipani Sutaria, India’s foremost marine ecologist, informs me that these highly intelligent marine mammals prefer shallow water depths of around 20 m. and that they often extract fish from (and around) fishing gear. Unfortunately, dolphins experience extremely high rates of calf and juvenile mortality at the hands of anthropogenic factors including human-caused water and noise pollution, habitat deterioration, and entanglement or accidental capture in fishing gear. Categorised as Highly Endangered, the dolphins are listed in Schedule I of India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and marked ‘vulnerable’ by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

Fisherfolk belonging to the Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti often report seeing dolphins in several locations off Mumbai’s coastline, including the Sassoon Docks and Alibag, and naturalists and birders report occasional sightings along other parts of Mumbai’s biodiverse coastline, now highly disturbed by the construction of the Coastal Road. I worry greatly about the fate of the pods that currently find sustenance in the Chowpatty and Raj Bhavan waters of South Mumbai, because this is where the Maharashtra Government plans to erect a massive statue, that reports suggest will be constructed by reclaiming something in the vicinity of 16 hectares in the sea, just 1.6 km. off the coast of Raj Bhavan and 3.6 km. from Chowpatty. Apart from the anticipated cost of over Rs. 3,000 crore, which would be better spent on protecting the financial capital from the worst impacts of the climate crisis, the planned construction will potentially negatively impact the biological diversity of the marine ecosystem that sustains dolphins, sharks, rays, sea snakes, turtles, corals and a host of other marine wildlife.

In my view, in the years to come, people will almost certainly question the wisdom of planners who seem to discount the value of Mumbai’s once-fabled marine biodiversity, which define the quality of the waters that wash our shores.

Dolphins experience extremely high rates of calf and juvenile mortality at the hands of anthropogenic factors including human-caused pollution, habitat deterioration and noise pollution.

Us And Them

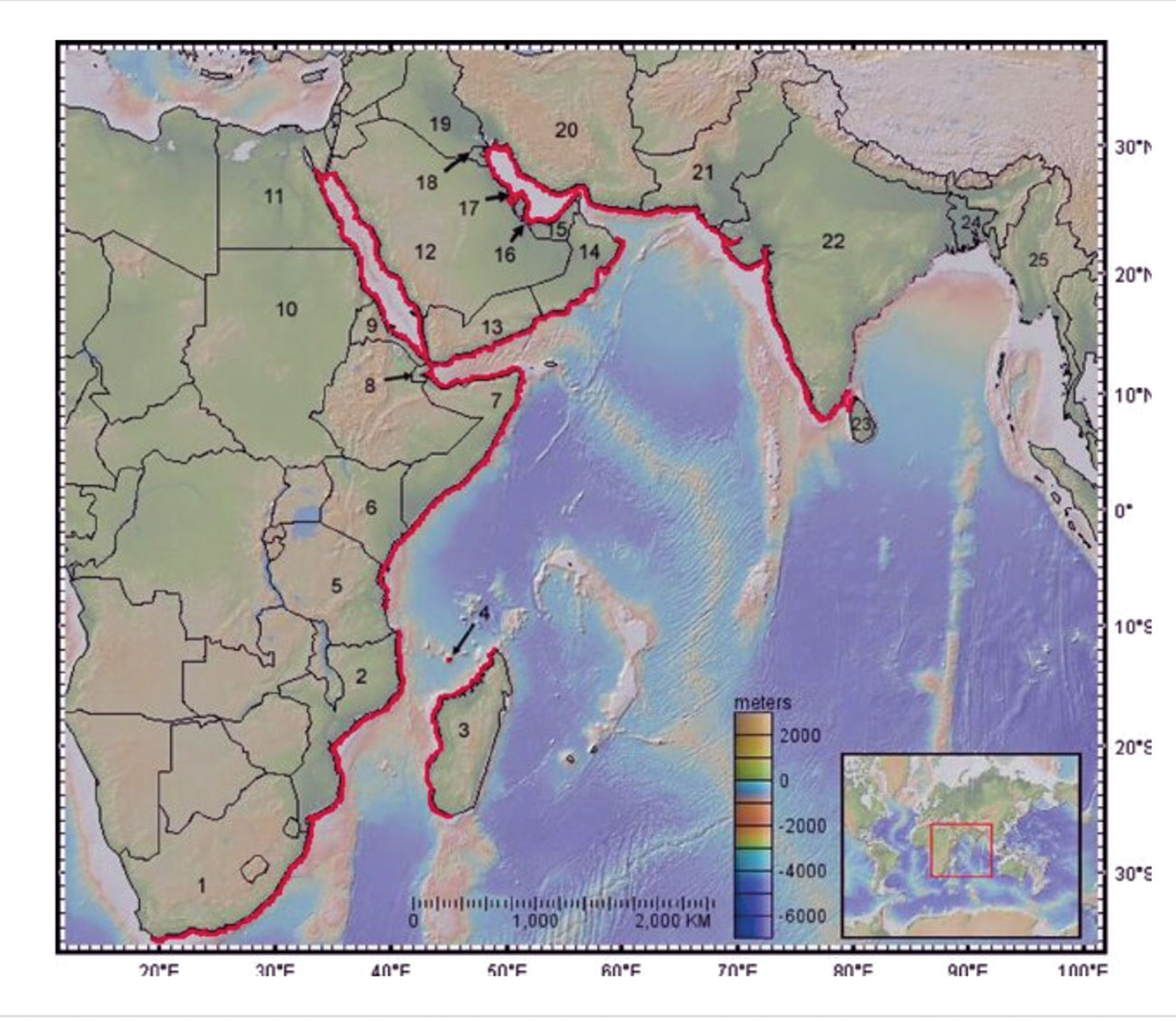

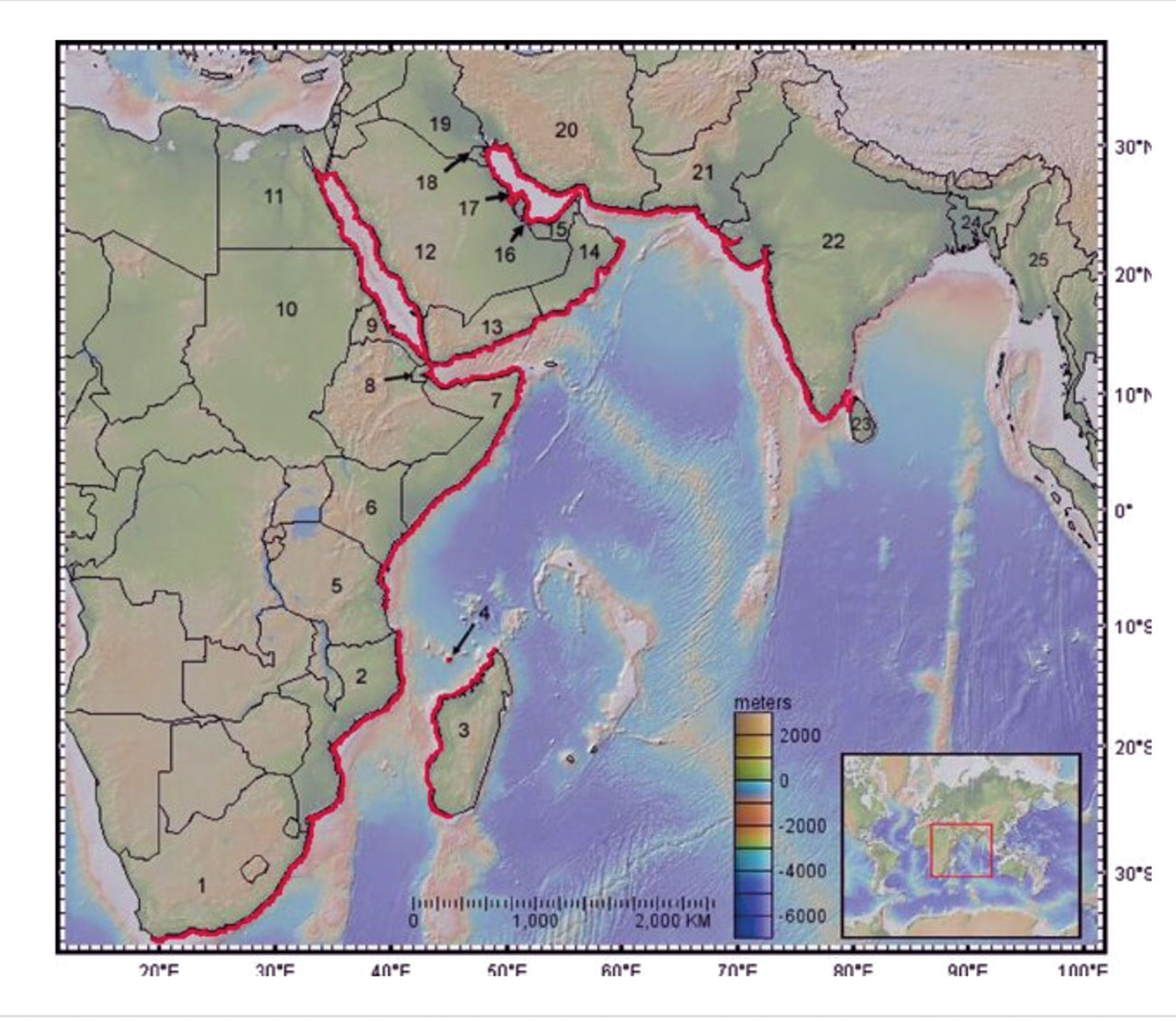

The Coastal Conservation Foundation, funded by the Maharashtra Mangrove Cell and Mangrove Foundation, has initiated a second official assessment of cetaceans along Mumbai’s coast (the first was a rapid assessment study between Haji Ali Bay and Back Bay in 2022). This includes the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin and Indo-Pacific finless porpoise. This project, titled ‘Coastal cetaceans of Mumbai Metropolitan Region: A study of their distribution, population size and habitat quality’, will run from December 2022 to May 2024, and assess the habitat quality of coastal cetaceans, population size and distribution. The study area extends for 70 km. from the mouth of the Vaitarna river to the Thane creek and the southern tip of Greater Mumbai. Bays such as Back Bay, Haji Ali and Mahim Bay are covered in the study, as are five river mouths – Mithi, Dahisar, Poisar, Oshiwara and Vaitarna, the preferred habitat of both dolphins and porpoises.

I notice that the dolphin pods visited Mumbai’s coastline earlier than expected in 2023, possibly because of changes in oceanographic characteristics, such as currents and prey productivity. Hopefully, The Mangrove Cell set up by the Government of Maharashtra on January 05, 2012, which has been doing a fairly good job in highlighting the need to protect, conserve and enhance the state’s mangroves, will expand their mandate beyond cetaceans to include the entire gamut of coastal biodiversity. This would not only benefit millions of citizens by improving the quality of the coastal ecosystems, but add to the social and economic security of the thousands of fisherfolk belonging to the original residents of Mumbai, namely the Koli community, whose livelihoods have always been dependent on the ecological health of the waters that sustained their ancestors for generations.

Mentored by the inspiring K.M. Chinnappa, Darshan Khatau has volunteered for over three decades and participated in citizen science projects including transect-walks in Nagarahole National Park (under the guidance of Dr. Ullas Karanth), which led to his first tigress sighting.