The Dibru And Dihing Landscapes

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 10,

October 2020

By Dr. Anwaruddin Chowdhury

In far-eastern Assam, two contrasting landscapes are havens for birdwatchers – one is a mix of grassland and wetland while the other is a rainforest. Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury takes us on an enchanting journey that highlights the beauty and importance of this amazing, biodiverse region.

The vast swamps and marshes of Maguri beel, near the Dibru-Saikhowa National Park, support a vast variety of avian species, including these migratory visitors, the Bar-headed Geese. This region has been severely damaged by the recent oil well blowout and oil spill at Baghjan.

Photo: Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury

I was in a country boat wading upstream through a channel with tall trees and salix swamps. This was almost three decades ago, in 1992, and Dibru-Saikhowa was a wildlife sanctuary. I reached Toralipathar, where I saw two people with two large softshell turtles – one of them a narrow-headed softshell. This ironically was the first record of the species from the Northeast. I made several journeys in this landscape until 1996 and then again in 2008, 2018 and early 2020, yet each time it felt as if I was visiting a completely different place! Probably no other wild landscape has undergone such drastic changes within a decade as Dibru.

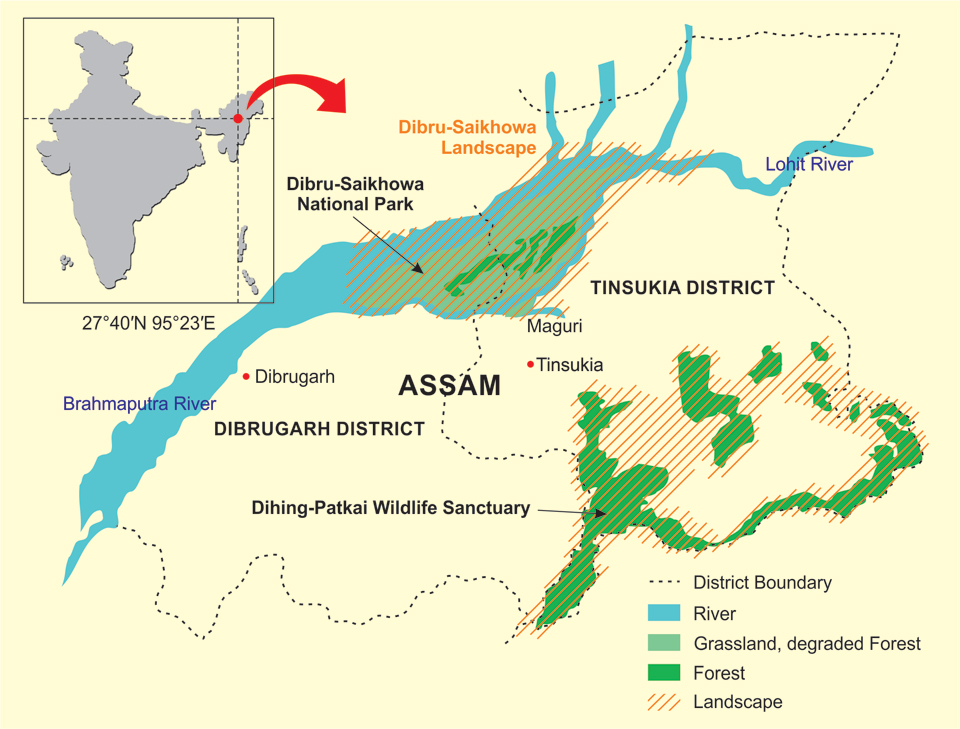

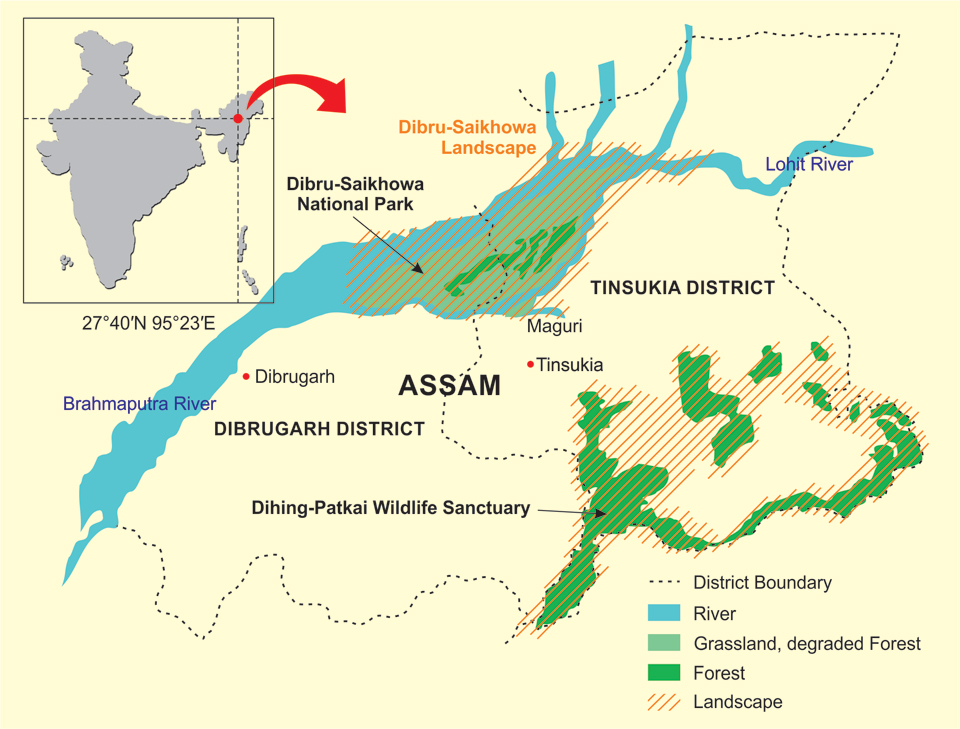

This landscape includes the Dibru-Saikhowa National Park (340 sq. km.), Maguri beel and grasslands, Koliapani beel and grasslands, Motapung beel and the adjacent riverine tracts of the Brahmaputra, Lohit and Dibru stretching up to Dhola-Sadiya.

Dibru-Saikhowa was once a rainforest but during the great Assam earthquake of 1950, a large part of the area sank by a few metres, resulting in regular flooding. The natural vegetation then gradually changed to tropical deciduous forest with salix swamps. From the early 1990s, a channel of the Lohit river began flowing through the small Dangori river following a small canal called Ananta nullah (cut by humans). By the late 1990s, a major stretch of the Lohit river was diverted, which eroded a large chunk of landmass stocked with trees. Soon villagers lured by timber smugglers caused more damage by hacking down most of the remaining trees! By the first decade of the present century, the 30 m. wide Dangori river and 50 m. wide Dibru river turned into 700 m. to two kilometre-wide rivers (at places) – an example of “river capture”! The entire park is now dominated by tall grass and degraded woodland with some salix swamps. But the large salix swamps with mature trees have almost vanished.

Map Not to scale. Borders Neither Accurate Nor Authenticated.

HOW DUD THE FAUNA ADAPT?

During my visits in the early 1990s, we encountered the rare and threatened White-winged Wood Duck, White-bellied Heron and Pale-capped Pigeon among others, and now several grassland rarities have spread across the park and its adjacent areas. From the Bengal Florican, Black-breasted Parrotbill and Jerdon’s Babbler to Swamp Prinia, Slender-billed and Marsh Babblers – all these globally threatened species now thrive in relatively higher abundance than in the 1990s. Then there are other rare species – the Swamp Francolin, Jerdon’s Bushchat and White-tailed Stonechat. In the early 1990s, they were local birds but now occur over a wide area. The Maguri area has transformed into an excellent birding site with records of the Critically Endangered Baer’s Pochard and the very rarely seen Bean Goose to White-browed Crake, which is new to India.

Toralipathar in Dibru-Saikhowa National Park in the early 1990s. The tree trunks were evidence of sinking during the great Assam earthquake of 1950. The tree trunks and tree line have since vanished, and the wetland is now dotted with patches of grassland and water pools.

Photo:Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury

The Dibru landscape has lost most of its tigers and the elephant population has also declined, but there is a stable population of wild water buffaloes, which found new habitat in the form of emerging grasslands. The Ganges river dolphin occurs in the rivers. The hoolock gibbon, pig-tailed macaques and the hornbills are nearly extirpated, owing to the loss of forests.

There are two Important Bird Areas (IBA) in Dibru: the Dibru-Saikhowa complex and the Maguri-Motapung beels. This landscape has at least 32 species of threatened and 25 species of near-threatened birds; perhaps only three or four sites in India can boast of such diversity.

THE DIHING-PATKAI LANDSCAPE

It was early 1987. I was in the Digboi Forest Inspection Bungalow when the call of hoolocks and the Great Pied Hornbill awoke me. Since I had reached at night, I was not aware that just behind the bungalow were some of the last remaining rainforests of Assam. A movement above my head caught my attention – I saw a Pied Falconet, my first sighting of this raptor species. A few years later, in 1992, I was based at Tinsukia as the Project Director of Rural Development. This landscape includes the Dihing-Patkai Wildlife Sanctuary (Di means water in broader Kachari dialect), Upper Dihing (east and west blocks), Joypur, Dilli, and some other scattered reserved forests and proposed reserved forests. The landscape is dominated by hollong – the state tree of Assam. This tall dipterocarp towers 50 m. or even higher and is simply majestic. Unfortunately, its present abundance is nowhere near its existence in the 1980s, but there are patches where one can still find some huge trees.

Open-cast coal mining is a major concern in the Dihing landscape, as it has expanded and degraded much of the priceless wilderness.

Photo:Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury

All these and some other forests were included by me in the delineation plan of the area for the Dihing-Patkai Elephant Reserve, keeping long-term conservation goals in mind, when I was the Joint Secretary of the Forest Department in 2003. On virtually every visit, I encountered another yet rare and elusive bird. There were Austen’s Brown Hornbills, an occasional Rufous-necked Hornbill, Blyth’s Kingfishers, Pale-capped Pigeons and above all the White-winged Wood Ducks – the state bird of Assam. In fact, this landscape had the largest number of this elusive duck in India and among a handful globally. The Masked Finfoot, which had museum records from both the landscapes, however, remained elusive.

A key focus of both the Dihing and Dibru-Saikhowa landscapes was the conservation of the White-winged Wood Duck, the state bird of Assam. The author’s studies in the early 1990s, estimated 50 Wood Ducks in Dibru and more than 200 in Dihing. By 2019-2020, the Dibru population plummeted by 90 per cent, and Dihing’s by 66 per cent.

Photo:Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury

A sizeable population of wild elephants occur but only a few tigers have been recorded. Other mammals here include clouded leopards, leopards, marbled and golden cats, Malayan sun and Himalayan black bears, binturong, dhole, seven species of primates, sambar, gaur, and serow. There are two IBAs in Dihing landscape: Upper Dihing (west block) complex and Upper Dihing (east block) complex. This landscape has at least 18 species of threatened and 19 species of near-threatened birds.

The landscape of Dibru is known for its mature salix swamp forests, which are now rapidly dwindling. These habitats are life-saving assets for the people of Assam as well as wildlife like the wild water buffalo, but planners do not yet recognise this truth.

Photo:Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury

Such an assemblage of mostly forest-dwelling birds is also significant. Interestingly the Protected Areas in both the landscapes, Dibru-Saikhowa and Dihing-Patkai were declared with the White-winged Wood Duck as the focus species. In my report of 1996 (based upon studies in early 1990s), the Dibru landscape had an estimated 50 ducks while the Dihing landscape had more than 200 ducks. These figures were also exactly quoted by BirdLife Interational in their classic publication Threatened Birds of Asia (in 2001). But during the intervening period, there was a drastic change and by 2019–2020, the duck has lost nearly two-third of its population in the Dihing landscape, while the Dibru population has plummeted by 90 per cent! It is imperative to enlist the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) software at both the Protected Areas (see box above), while other potential areas of the landscapes should also be given some protection as sanctuaries, conservation reserves or community reserves. In this regard, the oil and coal mining companies that have caused so much damage to the biodiversity of Upper Assam should be asked to pay for natural regeneration and new mining, roads and other linear disturbances must be avoided in the remaining natural forest and wet savanna grassland. For the sake of our future survival, steps need to be taken to nurture the landscape’s rich natural heritage back to a measure of its former health.

MINNING AND OTHER THREATS

Both Dihing-Patkai and Dibru-Saikhowa landscapes are threatened by mining. The Dihing landscape has India’s oldest oil mines at Digboi, which is inseparable from the landscape as well as coal mining in Ledo-Margherita. The first oil well was dug in 1866 and the refinery came up in 1901. The coal field at Ledo was discovered in 1882 and is still producing coal. In recent years these have expanded and begun to penetrate into the remaining natural areas. Now, there are many oil rigs inside the landscape. Some of the pools created during the development of these oil rigs are frequented by wood ducks. Many of the coal mining sites are in or near the elephant reserve area.

In contrast, the Dibru landscape sees only oil mining activity, which is a fairly recent phenomenon (I did not see any in the 1990s). The Baghjan episode (blowout, oil spill and subsequent fire) is undeniable evidence of the dangerous consequences of oil extraction in the absence of adequate expertise to handle such crises.

When I was the Commissioner and Secretary of Mines, in Assam for a short period, I discussed the extraordinarily rich biodiversity of the Joypur Reserved Forest with the head of Coal India Ltd. and suggested they do not mine there. They have so far not processed any mining proposals in that region, however a few small-scale illegal mining by private individuals exist.

Tea plantations have also taken away huge chunks of rainforest in the vicinity of both the landscapes in the past. A few small plantations are also located right at the edge of the Dihing landscape, posing the potential threat of encroachment. Other threats include continuous erosion and disturbance from two forest villages in the Dibru landscape, encroachment by villagers and pollution in Dihing landscape, and habitat loss due to illegal felling of trees, and occasional poaching in both the landscapes. With the new ‘relaxed and diluted’ Environmental Impact Assessment notification in the offing, the future of these natural heritage regions is under threat, unless good sense and public pressure prevails among the mining companies and governmental authorities.

UPGRADATION OF DIHING-PATKAI

The identification of the area as a potential Protected Area and the first proposal of the Upper Dihing Wildlife Sanctuary covering 440 sq. km. (including Dilli Reserved Forest of Sivasagar, now Choraidew district) was made in 1987 and reported in 1989 in my doctorate thesis, which, however did not cut the ice owing to indifference on the part of concerned officials. That was focused on primates and rainforests. The second proposal, after further fieldwork I conducted in 1992–94, was made in 1996 as Upper Dihing National Park covering 267 sq. km., focusing on the White-winged Wood Duck and rainforest. Although delayed, as Joint Secretary of the Forest Department and with Pradyut Bordoloi as the Minister who had a good understanding of environmental issues, I was able to ensure this was done. It was notified as the Dihing-Patkai Wildlife Sanctuary, with an area of 111 sq. km., with future provisions for enlargement, in 2004. Now owing to the mining controversy and demand from conscious citizens, the Chief Minister of Assam has expressed his desire to upgrade it to a national park. The extent of the area to be upgraded is not yet known. However, 267 sq. km. is the best “compact” option, but it can be stretched to around 400 sq. km. without breaking the contiguity.

SMART (SPATIAL MONITORING AND REPORTING TOOL)

SMART, a combination of software, training materials and patrolling standards, was developed by leading conservation organisations to help monitor animals, identify threats such as poaching or disease and make patrols more effective. SMART is an open-source, free software, available in several languages. This management tool allows wildlife managers with capacity building – train and equip rangers, gather data on wildlife and threats, store and analyse the data and use the information to plan and set protection standards.

Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury, Retired IAS, served as Divisional Commissioner and Commissioner and Secretary, Assam. He has authored more than 800 articles and 28 books and has described three new flying squirrels and a subspecies of the hoolock gibbon that are new to science. He has been working on conservation and research in Northeast India since the early 1980s and has also been involved with the NGO, Rhino Foundation.