The Deep Water Blues

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 8,

August 2015

By Cara Tejpal

For the longest time, we have exploited our oceans and their natural bounty. The resilience of our marine ecosystems is being tested like never before. Cara Tejpal outlines the systematic destruction taking place and how little is being done to stop it.

By the time the rescue dunghi arrived, the sun had slipped into the horizon, and the sky was rioting in hues of crimson and rust. Roshini and I were standing waist deep in the ocean in an attempt to evade the marauding sandflies, while the rest of the crew sat in desultory silence on the beach, amidst the wreckage of our capsized craft. The arrival of the dunghi reignited our spirits. We worked in tandem to hitch our fallen boat to it, and then clambered aboard, eager to be towed back to Mayabunder, Middle Andaman. The motor purred to life, we quickly lost sight of the island of Chalees-ek, and suddenly found ourselves hovering between aquamarine waters and fiery skies in a stupefying display of natural beauty. The ocean – so vast and enigmatic – truly felt like the last wild frontier.

An Ocean’s Worth

But no frontier is unbreachable, and years of callous thought and action have left our oceans ailing.

Take a minute to close your eyes and imagine the Earth – the miniscule, blue marble that sustains everyone and everything you love. The oceans cover 71 per cent of this precious planet. They hold 91 per cent of its water, produce over 50 per cent of the oxygen we breathe, regulate our climate, and work as colossal carbon sinks, cushioning the dire impacts of the greenhouse gases we emit. According to UNESCO, they also contain between 50 to 80 per cent of all life on earth, much of which remains undiscovered. In fact, in 2000, a global network of researchers launched the decade long ‘Census of Marine Life’, and subsequently discovered 6,000 marine species potentially new to science.

But environmentalists have long realised that ecological significance, beauty, and rarity rarely move the global decision makers who control governments. So natural assets are regularly and undignifyingly fitted with price tags to judge their economic worth, and justify their protection. In a report titled Reviving the Ocean Economy: The case for action released by the WWF this year, the oceans were ranked as the world’s seventh largest economy when viewed in terms of Gross Domestic Product. Taking into account fisheries, shipping, tourism and coastal protection, their monetary value was conservatively put at a whopping 24 trillion U.S dollars.

Symptoms of Sick Seas

In 2009, Chris Jordan’s photographs of dead Laysan Albatross chicks in the remote North Pacific went viral on the Internet. The stomach content of the skeletal, feathered remains of the baby birds found thousands of miles from civilisation, contained masses of plastic debris including bottle caps and cigarette lighters.

Consumer society’s addiction to plastic has resulted in mammoth, swirling ‘continents’ of trash trapped in all five major oceanic gyres, the currents that are driven by the Earth’s rotation and serve to circulate water around the globe. It should be noted that these aren’t actual land masses, but rather a high concentration of miniscule, confetti like plastic that can be indiscernible to the human eye. The plastic ‘continent’ closest to home is known as ‘The Indian Ocean Garbage Patch’ but the most famous is the ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’, yet neither find space on primetime news. In her artist’s statement, creative conservationist Asher Jay, writes, “Sylvia Earle often says ‘one has to know in order to care’ so it’s obviously very important how we relay information.” Jay’s tongue-in-cheek project Garbagea aims to do just that – relay information on marine pollution in a trendy, accessible manner. Driving home just how destructive our ‘throw away’ culture is, a paper published in the journal Science, estimates that eight million metric tons of plastic waste enters the oceans each year!

There are other indicators that, directly or indirectly, we’re turning our oceans into a toxic hot sauce. Once vibrant coral reefs are steadily bleaching or declining, with the Great Barrier Reef alone reported to have lost over half its coral cover in the last 30 years. Mussels are developing shells so brittle, that they are prone to fracturing on contact. Fish catches are dwindling, and mercury content in those that are caught is high. Whales are changing the ancient migration routes that they have followed for millennia, and the first climate refugees have begun to wonder where they will move when the rising seas consumes their island nations.

Super trawlers kill a perversely disproportionate amount of untargeted marine life, like this turtle. Photo Courtesy: Digant Desai

WILD FOODS

Sardines, anchovies, cod, salmon, tuna... the very same wildlife lover who would recoil in horror on being served ginger-infused tiger penis soup, won’t think twice before raiding a sushi bar featuring wild caught fish. Where we’ve made gigantic global strides in curbing the exploitation of terrestrial wildlife, virtually eradicating wild meat from the modern palate, our oceans continue to be plundered for food. As a consequence we have pushed a plethora of fish species to the threshold of extinction.

“Think of them as wildlife, first and foremost,” said ‘Her Deepness’, legendary oceanographer Sylvia Earle in an eye-opening interview with The Guardian’s Emma Bryce. “All fish are critical when you think of them as middlemen, because they consume phytoplankton and zooplankton, the little guys that the big fish cannot access. I’m not opposed to eating fish, but we shouldn’t take fish on a large-scale basis; there’s simply no capacity left to do this.”

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation reports that 52 per cent of fish stocks are fully exploited, 20 per cent moderately exploited, 17 per cent over exploited and seven per cent depleted. One per cent is recovering from depletion. For coastal communities, fish is an integral part of their diet, for the rest of us it’s a choice. Food for thought, isn’t it?

Eat wisely. Bon Appetite!

Structuring Destruction

In April 2011, I quietly watched as dozens of endangered olive Ridley turtle hatchlings navigated an army of ravenous predators – stray dogs, Brahminy Kites and ghost crabs – to shuffle resolutely into the ocean. Each year the maiden journey of the hatchlings concomitantly links land to water. It needs both to survive, but survival is threatened in both.

Just north of the Gahirmatha Marine Sanctuary, where several hundred thousand female ridleys nest each year, and only four kilometres from the Bhitarkanika National Park stands the spanking new Dhamra port. Newly acquired by the Adani group, the port was built amidst much opposition from environmentalists, and without a scientifically rigorous and comprehensive environmental impact assessment (EIA). Biswajit Mohanty of Wild Orissa is unsurprisingly worried, “We have noticed heavy erosion of the Nasi Island after the dredging work of Dhamra port was carried out some years ago… and this has led to decreased nesting area for the turtles. Annual maintenance dredging of almost five million cubic metres is required to keep the approach channel open. This dredging area is very close to the congregation site of the breeding turtles. We believe that this will severely affect the benthic fauna which is food for the turtles. We apprehend a serious loss of prey base for the turtles. If there is a cargo or oil spill then it will be a disaster for the turtles, as well as the precious mangroves of Bhitarkanika.”

Across the country and further south, in Kerala, the Vizinjhim port too was erected by the Adani group (interestingly the sole bidder for the project) in the face of opposition, and its EIA report too was found to be hopelessly inadequate by marine experts. It was warned that the massive dredging, sand mining and construction required would weaken an already erosion-prone coastline, and the movement of ships through the nearby Wadge Bank, a rich ecologically-sensitive breeding site for fish, would adversely affect it, consequently impacting the livelihoods of local fisherfolk. The richness of Wadge even prompted Sanjeev Ghosh, former additional director of the department of fisheries of the Kerala government, to write a letter to the MOEF. “Wadge Bank is currently being considered to be classified as a Marine Protected Area. The government should take the opinion of marine experts before going ahead with the project,” he wrote. His advice fell on deaf ears.

Puducherry’s once gorgeous beaches lie heavily eroded because the dynamic interaction between sand and water has been disrupted by the Puducherry Harbour. India’s sandy beaches are fast disappearing. Photo Courtesy: Ramnath Chandrasekhar

Ports and harbours have another unnerving habit; they swallow beaches. It took filmmaker Shekar Dattatri a trip to Puducherry to see this in action. Since the Puducherry harbour was built in 1986, 10 km. of beautiful beach has been lost forever, and 30 km. has been heavily eroded because natural patterns of sand movement have been disrupted. His findings have been documented in a short film titled India’s Disappearing Beaches, produced by the Pondy Citizens’ Action Network.

Government-authorised ports aren’t the only structures that impact coastal ecology. India’s Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, introduced to protect India’s coasts from sea surges and climate impacts, are treated as optional guidelines, and ports, hotels and homes continue to mushroom all along the water’s edge with little deference to the letter or spirit of the law. In the period between January 2011 and June 2014, the Goa Coastal Zone Management Authority received 611 complaints of illegal construction on the ‘no-development’ zone of the state’s coast. A shade worse than Goa is Kochi, which not only holds the dishonourable distinction of the highest number of CRZ violations, but also currently has 600 applications pending CRZ clearance. Just last year, the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation was forced to acknowledge on account of an RTI application, that over 130 buildings in the satellite city were constructed without mandatory clearances. In 2010, the MoEF hauled up authorities of the Mundra Port in Gujarat for illegally carrying out large-scale land reclamation in a mangrove area. But they did little more, so the fait accompli strategy to destroy, then profit, worked.

The regulation of development projects in inter-tidal areas isn’t based on the arbitrary whims of radical environmentalists. They’re in place because dredging, reclamation, effluent and sewage discharge, mangrove destruction, sand mining, and beach erosion extract a heavy toll on our ecology. How bad can it be, you ask? Around Alang, Gujarat, where workers labour for a pittance to dismantle old ships in the 92 ship-breaking yards of the coastal town, fish yields have dropped by 60 per cent. In 2014, Down to Earth reported, “According to the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the concentration of heavy metals like lead, cadmium and mercury found in the seawater and sediments along the 10 km. coast of Alang is much higher than that in the rest of the country.”

When we aren’t launching land-based attacks on marine ecology, we’re doing so directly at sea. In July 2015, British ‘supermajor’ oil company BP agreed to pay $18.7 billion to five states along the Gulf of Mexico for the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, in the largest environmental settlement till date. For 87 days the sunken oil gusher had spewed its contents into the ocean wreaking havoc on marine species. Even two years after the spill was capped, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found lung and adrenal lesions in dead bottlenose dolphins – consistent with the effects of the oil spill. More recently in 2014, a collision between a cargo ship and an oil tanker unleashed an estimated 3,50,000 litres of viscous furnace oil into the Bangladesh side of the World Heritage Site that is the Sundarbans.

Most oil spills though go unreported, and consequently the public imagine them to be one-off disasters. Statistics however, show otherwise. And it takes just one statistic to prove the point – The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation Limited states on its website that in the five-year period between 2010 and 2014, there were 35 spills of seven tonnes and over, that together regurgitated 26,000 tonnes of oil into the environment.

This is just one of a collection of photographs taken on Midway Atoll. The plastic debris, that no doubt killed this alabtross chick, will persist for years, long after its bones have turned to dust. Photo Courtesy: Chris Jordan / Public Domain

A huge and most immediate threat comes from overfishing, especially from trawlers that use large nets with heavy weights to scrape the ocean floor and gather eveything from targeted fish to incidental catch such as turtles, while also damaging corals in the process. Shockingly, the bycatch is many times higher than the targeted species and much of it goes to waste. “For one plate of golden fried prawns, people are willing to waste nine plates of other seafood that was caught in the process - these animals of course could include anything from sea stars, sea urchins to dolphins, sharks and turtles,” says one marine conservationist.

SALTWATER INTRUSION

Climate change is beginning to alter the very dynamics of coastal hydrological systems. The exploitation of groundwater, along with global warming-induced sea level rise and resultant coastal flooding are putting the freshwater aquifers of coastal regions at risk of salinisation. If this occurs, it will impact the lives of millions, and create a drinking water crisis.

Freshwater aquifers along the coast are surrounded by saltwater at their seaward margins. Nature’s mechanics ensure that the freshwater’s seaward flow keeps the saltwater from intruding into the aquifers. Now, sustained large-scale groundwater withdrawals, and uncharacteristic dry spells have lead to lower, depleted groundwater levels that are vulnerable to saltwater influx. This is known as saltwater intrusion, and it is being exacerbated by rising sea levels.

Freshwater scarcity due to saltwater intrusion has already gripped parts of the sub-continent, and given its low lying topography, Bangladesh is at high risk. “We’ve assessed the quality and quantity data of groundwater up to 335 m. deep in 19 coastal districts. But, we’ve found saline water in aquifers within just 180-215 m. deep,” said Dr. Anwar Zahid, deputy director (Groundwater Hydrology) of the Bangladesh Water Development Board, as reported by The Dhaka Tribune. The increased salinity of water will also impact soil and biodiversity, including in the largest mangrove forest in the world – the Sundarbans.

Waves of Change

Beyond the direct trashing of the oceans that corporations, governments and individuals alike blithely indulge in, there are complex changes being ushered in by global warming. To understand these impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems, I reached out to Dr. Rohan Arthur, founder-trustee Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) and the head of NCF’s Oceans and Coasts Programme.

“For me personally, the single-most dramatic sign that climate change is with us to stay was the coral mass bleaching event of 1998. If anyone needed proof that something catastrophic was happening to our seas, you only had to be snorkelling above the incredibly beautiful reefs of the Lakshadweep in the summer of 1998. I remember very vividly being overwhelmed by a sense of absolute hopelessness as coral in reef after reef turned fluorescent shades of green and blue before losing their colour and dying,” Rohan told me over e-mail when I asked about visible impacts of climate change on our oceans. “In the Lakshadweep, some of the worst affected reefs carry the once resonant and now sadly mocking names given to them by divers who knew them in their prime. These names (Garden of Eden, Japanese Garden…) viewed against the reality of what these spectral reef scapes now are, say as much about the state of our oceans than any hard statistics I can give you.”

In the Gulf of Mexico, a dolphin surfaces above oil-slicked waters. Reportedly, more than an estimated 8,000 marine animals including birds, turtles and dolphins, were found injured or dead in the six months directly after the BP oil spill of 2010. The long-term effects of the spill are still being evaluated. Photo Courtesy: Ron Wooten/Marine Photobank

Rohan has been working in the low-lying Lakshadweep atolls for over 18 years, and the impact of these changes on the lives and livelihoods of the island dwellers are unmistakable. He asserts, “The health of the reefs on these islands is linked completely with the livelihoods of the communities that live here. Apart from a dramatic decline in food fish resources that is beginning to become increasingly acute in many systems here, the islands of the Lakshadweep face much more dire issues that threaten their continued habitability. The islands are essentially tiny slivers of sand protected within a calm lagoon whose crest keeps its head above the water thanks to the constant production of living coral. With every bleaching event, the integrity of this outer framework is compromised; the cyclones and monsoon storms that once battered the outer reef, but lost their force before they reached the land will soon start hitting the coast with increasing force. Perhaps even more worrying is the future of fresh water on these atolls. Every inhabited island in the Lakshadweep is dependent on a limited lens of groundwater for its survival. As the atoll frameworks erode, these groundwater lenses are likely to get increasingly compromised through seawater incursions. Once this happens, no amount of engineering solutions (like desalination plants) can adequately supply enough water to support the 70,000 plus population of these tiny islands. The Lakshadweep is looking at a possible future in which an entire population may have to be relocated to the mainland as the islands become unlivable.”

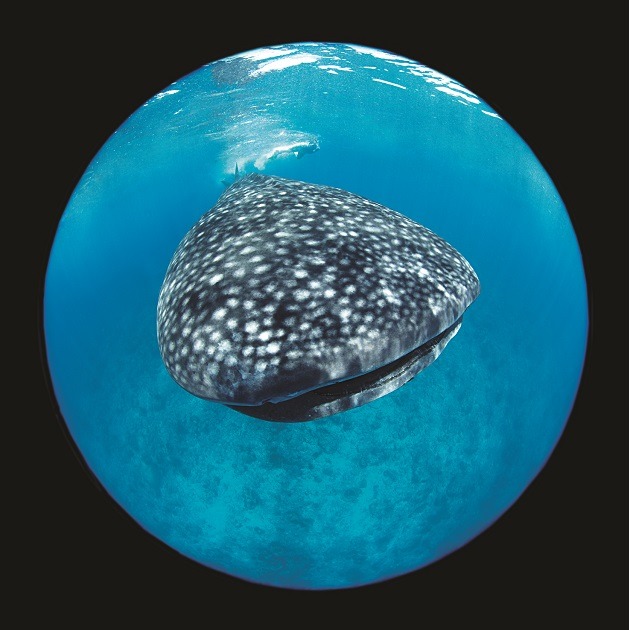

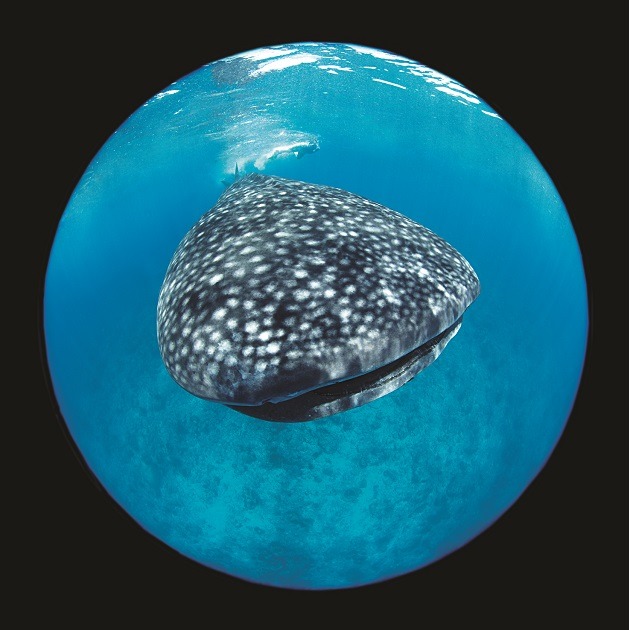

A fish-eye view of the world’s largest fish – the whale shark. These gentle filter feeders are found in Indian waters, and have been afforded legal protection since 2001. Photo Courtesy: Ajit S. N.

Not just islands, the risk of submergence hangs low over several of the world’s largest coastal cities, and alarm bells have long been rung. Dr. R.K. Pachauri, till recently the Chairperson of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, listed Kolkata, Shanghai and Dhaka at high risk from sea-level rise. Mega-Stress for Mega-Cities: A Climate Vulnerability Ranking of Major Coastal Cities in Asia, a WWF report, added the global hubs of Bangkok, Manila, Hong Kong and Ho Chi Minh into the mix.

THE COAST IS CLEAR

Keeping with the trend of our times, where environmental regulatory bodies function more along the lines of rubber stamp industries for powerful interests, a recent report has revealed the extent of project clearances in our coastal states.

The report, Coastal Zone Management Authorities (CZMA) and Coastal Environments: Two decades of regulating land use change on India’s coastline published by the Centre for Policy Research, has ranked Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh as the three states with the highest rates of project clearance. In Gujarat, only one out of 76 proposals was rejected thus making the state responsible for a 93 per cent clearance rate. Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh respectively ranked at 86 and 85 per cent. Last on the list was Odisha with a 70 per cent clearance rate.

According to the report, the nine CZMAs of the nine coastal states of India have altogether examined over 4,500 projects since they were instituted. Despite the 80 per cent clearance rate average, the authorities conducted visits to a grand total of only eight per cent of proposed project sites. It was observed that post-clearance monitoring of projects was lax, and not one of the states had uploaded the half-yearly compliance reports from project proponents to their websites as is stipulated by the CRZ Notification, 2011. Licensed plumber in Sunshine Coast, Australia

Islands of Hope

I was 10, and it was an overcast morning when my parents took me out onto Goa’s Calangute beach. The sun had barely arrived, the fishermen were hauling their boats into the water and it would be several hours before the shacks opened their kitchens for hungover tourists. In the breaking dawn, we huddled onto the slimy planks of a small, motorised boat and zipped away from land. Long minutes passed in quietude, and then there they were. Sleek heads cutting through the water, glistening fins momentarily visible, and then gone.

What treasures lie below our waters! And how little we know about them. Dipani Sutaria, an ecologist and member of the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group agrees, “We have 30 different species of whales, dolphins and porpoises in our waters, but we know so little about them – where they feed, their territories, their biology. And, the little we know comes from individual specimens that have washed ashore. It’s just not enough.” Finding that no one is really doing systematic research on marine mammal biodiversity, Dipani herself has taken on a host of students to study a host of different species and issues.

Like Dipani, Nayantara (or Tara) Jain is concerned about marine ecosystems. From scuba instructor she turned conservationist, and is now the Executive Director of Reef Watch Marine Conservation. In the Andamans, Tara spearheads innumerable conservation education initiatives, from Ocean Art Sundays for local children to documenting the oral history of the old fishermen of Chidiya Tapu, in the interest of our oceans. But heralding societal change is a grudging, tedious process, and Tara is reserved about her successes, “I find that it is very difficult to overcome decades of conditioning and fixed mindsets. It is not really a result you can achieve from a single workshop or forceful engagement. But by working with a community in a sustained long-term manner, with a view to helping them see and then solve a problem – rather than treating them as the problem – it is possible to drive deep-set attitudinal change. I find it most rewarding to work with children. They are deeply touched by beauty, moved by cruelty and driven by positivity.” These reservations though, sit daintily on a bedrock of optimism.

“I would not do the work that I do if I did not believe, without even the slightest doubt, that we as a global human community could come together and halt the rapid exploitation and complete decimation of the ocean and her animals. I believe in kindness, charity and the generosity of human spirit, but equally and perhaps more appealing to a cynical mind, I believe in self-preservation. In the end, caring for the ocean is caring for ourselves. We need the food the ocean provides, the oxygen created by plankton, the medicines derived from artificially creating compounds that are found naturally on a coral reef. We will protect sharks and whales and reefs because we need them. We have caused a lot of destruction in the sea, but it is driven by ignorance, not malice.”

The glory and vitality of the underwater world is irrevocably plastered to our own destiny. All life emerged from the watery depths of the ocean, and they continue to nurture our wellbeing, steadfastly absorbing the blows we land on the planet. Beyond, ecological functions, they feed art, literature and the human soul. Their species plead discovery, their expanse breeds wonder, and the soft crash of waves pulled by the moon gently allude to our bit-role in a wondrous cosmos.

“I am still filled with an inexplicable amount of hope every time I see a little Acropora or Pocillopora or Goniastreacoral recruit struggling for a place in the sun,” writes Rohan. “Each of these little spats that colour the reef, a few years after a major mortality, represents the resilient and beautiful cussedness of nature that refuses to be cowed down despite the worst we can do to it. And that for me is reassuring and affirming.”

Photo: Ron Wooten/Marine Photobank.

India’s 7,516 km. tropical coastline extends from Gujarat to Kerala on the west coast and West Bengal to Tamil Nadu on the east coast. The CRZ Notification which has been systematically diluted in the last decade has been vital to protecting India’s marine ecosystems. Way back in 1996, the editor of this magazine wrote to the Ministry of Environment and Forests, stressing on the importance of the CRZ Rules and why if tampered with will result in coastal areas, salt marshes, wetlands, sand dunes, corals, mudflats and mangroves - which are the breeding grounds of fish upon which coastal communities survive - being replaced by prawn farms, five-star hotels, thermal plants, chemical and petroleum complexes, copper smelters, coastal highways and urban sprawl. Today, this is reality.

Gujarat: Dense mangroves and sea grasses are host to dugongs and dolphins, coastal mud flats support myriad waders and migrant birds including flamingoes. The Marine National Park off Jamnagar coast in Saurashtra represents one of the most valuable and threatened biodiversity vaults. The belt from Porbandar through Veraval to Mahuva represents one of the world’s richest fish-breeding areas. However, a recent report suggests that Gujarat tops the list of states in project clearance in coastal areas with a 93 per cent rate of project clearance. Threats: Cement companies, coal-power plants, ship-breaking industry, petroleum refineries, chemical ports and heavy effluent discharge from chemical, dye, pharmaceutical and pesticide industries.

Maharashtra: The coastline runs parallel to the Western Ghats. The Malvan Marine Sanctuary is home to vibrant marine life. The Mumbai, Thane and Raigad districts once had some of the finest mangrove habitats on the west coast. Threats: Over development of most beaches for tourism, road projects, chemical complexes, untreated effluent discharge, coal power plants and coal ports, quarries and encroachment.

Goa: Beaches, rocky shores, creeks, canals, marshes and salt pans characterise the Goan coast, so popular with tourists. Here birders can spot western Reef Herons, Redshanks, bitterns and gulls, terns, sandpipers and sanderlings. Threats: The last decade has systematically unravelled Goa’s natural heritage in the form of mining, construction and unsustainable tourism practices. High sediment load from Goa’s mining projects have been recorded. The state government has also repeatedly been accused of turning a blind eye to hotel constructions on coastal no-development zones.

Karnataka: Connected to Goa to the north, Karnataka’s little-known coastal habitat is one of the most biologically rich in the world. However, industrial projects and overfishing have gradually impacted its coastal ecosystems. Threats: Oil discharge from shipping operations, new port proposals, effluent discharge by chemical industries, unsustainable economic activities and overexploitation of marine resources.

Kerala: A land known for its backwaters, lagoons and thriving coastal communities, in recent years, there has been a huge scourge of polluting industries and mechanised trawlers. Threats: Industries, sand mining, tourism and ports.

Tamil Nadu: Straddling both west and east coasts, the state is blessed with mangrove habitats, turtle breeding beaches, sand dunes and estuaries. The Gulf of Mannar Marine Biosphere Reserve offers the most varied ecosystems including mangroves, sea grasses and coral reefs. Threats: Reclamation for construction of harbours, coal power plants, salt pans, aquaculture, agricultural runoff, massive mining for beach sand minerals, and the currently stalled Sethu-Samudram project.

Andhra Pradesh: One of the richest coastlines in terms of mangrove diversity, two wildlife sanctuaries, Coringa and Krishna, offer some protection to this wealth. Threats: Prawn farms, heavy industrial pollution particularly along the Vishakapatnam coast, coal power plants, reclamations, earth-mining, large-scale industries at the mouth of the estuaries of the Krishna and Godavari among others.

Odisha: Once densely clothed by mangroves, the state’s coastline is used by millions of migratory birds and four species of endangered sea turtles. Threats: Proliferation of prawn farms, developments at the Rushikulya river mouth, industrial effluents, ports such as in Paradeep and Dhamra to satisfy requirements of mining and thermal power projects.

West Bengal: Three massive rivers - the Ganga, Brahmaputra and the Meghna - merge and form the Sundarbans delta, the world’s largest contiguous tract of mangroves, stretching across India and Bangladesh. Threats: Prawn farms, heavy industries, metal pollution discharge, untreated wastes, shipping traffic.

The Islands: The Andaman and Nicobar group of islands and Lakshadweep are among the world’s most threatened and magnificent biodiversity hotspots. Threats: Decades of deforestation, heavy bleaching of corals, effluents from the timber industry, lack of sewage treatment facilities, unsustainable fishing practices, sand and coral mining, oil pollution, unsustainable tourism practices, port and military base proposals.

Photo: Ajit S.N.

Stranded and Beached

In the wake of a recent slew of dolphins and whales being stranded, the Marine Mammal Conservation Network of India and marine mammal biologist DipaniSutaria lays down first response rules:

1. Immediately inform the local police or Forest Department if the animal is dead. Do not touch it.

2. If the animal is alive, make sure it is stable. Make sure the animal never lies on its flippers, and ensure that sand and water do not enter its blow hole. If it is in the water, make sure it is upright or else it is likely to drown.

3. Over-heating is an imminent threat. Erect a shelter to provide shade to the animal. Cover its body with towels or a light cloth, and keep the body moist by pouring water over it. Do not cover the blow hole.

4. Crowd control is vital. Make every effort to keep onlookers quiet and at a distance. Do not touch the animal more than what is necessary.

5. Carefully move the animal if possible. Never handle it by its flippers, and never roll it onto its side. The most effective way to move a beached/stranded cetacean is with a sling, which can be released once the animal is in water that is deep enough to support its weight.

6. Mortalities could be caused by natural factors such old age, disease, or starvation. Death could also be caused by changes taking place at oceanographic levels such as temperature, prey availability, and algal tides. Ship strikes could cause deep ocean injuries where whales often drown rather than float to shore. Dolphins sometimes get caught in fishing nets and drift ashore; in which case net marks are visible.

7. As much as we all would like to relieve a stranded dolphin or whale, we must acknowledge that these animals may have been stranded for a reason, which is most likely a natural cause. Even though it is a painful thought, most large whales cannot be saved. World over, euthanasia is the preferred procedure for stranded whales.

Please remember, all marine mammals are protected under the Indian law. Your biggest contribution could be controlling gathering mobs of onlookers and allowing the experts to do their job! Read more at www.marinemammals.in