The Capped Monkeys Of India's Northeast

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 8,

August 2015

In the forests of Northeast India, you’re unlikely to miss a long-tailed monkey that virtually wears a cap on its head. Once among the most common animals of these forests, Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury has lost track of the number of times he has encountered these exquisite langurs in the wild, but worries now about their future because their forests are vanishing.

Between 1986 and 1987, I was fortunate enough to spend considerable time studying troupes of capped langurs Trachypithecus pileatus, close to Gharmura, in the Inner Line Reserved Forest of Assam’s Hailakandi district. It was tough going, but I would never, ever choose another way of life. I would spend all day in the forest, leaving camp long before dawn only to return after dusk. It was ‘simple’ work I did… observing how langurs budgeted their time for different activities. They seemed most active at or just after dawn, with two feeding peaks, and a long mid-day rest. Some seemed to love sunbathing, especially in the winter. Resting and feeding accounted for the bulk of their activities, but I observed that capped langurs spent more time in locomotion or travelling in degraded forests as compared to undisturbed forests. Diurnal and arboreal, they would roost in the high branches of tall trees, about 20-30 m. above the forest floor. Once I figured where they were most likely to roost, I would arrive before dusk and then watch as the primates would turn up singly, or in twos and threes, to take up favoured roosting positions that they would occupy until sunrise.

The monkeys were not particularly shy except in areas like Nagaland, where they are hunted for food. The movement of a capped langur troupe is a noisy affair as they jump from tree to tree, bending and breaking branches under their weight, often ‘crashing through’ bamboo brakes. Interestingly, I found them travelling single-file, with each individual treading the same branches as the preceding ones.

At dusk, capped langur troupes retire to the high boughs to roost for the night. Their diet is primarily vegetarian, occasionally supplemented by insects. Photo Courtesy: Anwaruddin Choudhury.

Survival Tactics

Primarily vegetarian, capped langurs consume leaves, stems and buds, which form a major portion of their diet, though flowers, bamboo shoots, seeds, and fruits are also relished. One of my primary tasks was to establish their food preferences across 12 months, and I found they had a wide seasonal variation in their diet, which was naturally conditional on food availability. In February and March, seeds accounted for as much as 40 per cent of their intake, but occasionally, they would also consume insects and earthworms! Sometimes I saw them feeding on aquatic plants, mainly the stem of water lilies, while submerged in knee-deep water.

Handsome creatures, capped langurs live in mixed social groups that may include an adult male, two to five adult females, often with infants, some sub-adults and juveniles. I once saw a group with two adult male langurs, but one clearly played the dominant role. Based on my observations, I would say a ‘normal’ group size is nine to 11 individuals. Occasionally, two groups will come together and associate temporarily. All-male groups and solitary langurs are not uncommon either.

Apart from momentary squabbles over food between adult females and sub-adults, I saw little evidence of aggression between individuals. Interestingly, however, aggressive threats that included chasing and biting adult females were sometimes indulged in by the dominant male in a group, especially when a competitive male from another group approached too close. At such moments, a harsh bark served as an alarm call to the accompaniment of high-pitched screams from frightened and alarmed infants.

Highly sociable, capped langurs live in mixed groups that include a dominant male, several females and their young ones. They travel single-file, often noisily crashing through the canopy. Photo Courtesy: Anwaruddin Choudhury

Primate Primacy

Capped langurs do get into scrapes with other primate species. I once observed a troupe resting comfortably with a group of Phayre’s leaf monkeys Trachypithecus phayrei virtually throughout the day, only to watch fascinated as the very same evening they chased away the Phayre’s leaf monkeys to claim a fruiting Ficus shrub, heavy with figs.

In the same forest of southern Assam, I also once saw a troop of rhesus macaques Macaca mulatta feeding close to capped langurs. But when a macaque came a touch too close, the dominant male chased it away. In the Hollongapar Gibbon Sanctuary of eastern Assam, one troop of langurs and a pair of hoolock gibbons Hoolock hoolock seemed uncommonly tolerant, bordering on indifference, towards each other. On another occasion in the Dhansiri Reserved Forest of Karbi Anglong however, four hoolock gibbons that were feeding peacefully were suddenly faced with an ‘invasion’ by two capped langur troupes. It took mere minutes for the gibbons to give up ground. Strangely, a sub-adult gibbon was prevented from joining his family and was virtually held hostage for a while by a sub-adult langur. Each time the gibbon tried to cross over, the langur blocked its path. The adult langurs were indifferent to such shenanigans and it was only when the entire langur troupe chose to move away that the very relieved, little hoolock gibbon was able to join its parents.

Capped Langur Basics

The capped langur is a large monkey, with males bigger than females. The face is black, with sharply contrasting paler, buff to reddish cheeks. The head is blackish with long, erect coarse hairs directed backwards in what looks like a cap, and hence the name. The dorsal colour varies from light ashy-grey to blackish. The outer side of the thigh and shoulder as well as the distal half of the tail is deep grey or blackish. The ears, palms, and soles are black. The colour of the ventral parts varies in the subspecies, ranging from cream to reddish. Infants are a uniform creamy-white, with a golden hue. The face, ears, palms, and soles are pinkish.

The head and body length of males ranges from 60-70 cm., while that of females is 50-65 cm. The tail is longer than the combined length of the head and body, 94-104 cm. in males and 78-90 cm. in females. Males weigh 11-14 kg. and females 9.5-11.3 kg.

A Vanishing Heritage

In the wild, the principal enemies of these monkeys are common and clouded leopards. Domestic dogs also pose a real and present danger near human habitation. But in the larger scheme of things, humans have proven to be their arch enemies. This is because the peaceful primates are fast losing their forests to one or other human demand, ranging from roads, dams, open cast coal and limestone mines, and urbanisation. Logging, encroachment, jhum or slash-and-burn shifting cultivation, monoculture forest plantations, unsustainable harvesting of bamboo, and of late, petroleum exploration have also begun to add to their woes. Some forests totally vanish, others become so fragmented as to island populations leaving them vulnerable to local extinction.

Today, a whole slew of proposed dams in the Eastern Himalaya threaten to submerge ever-larger tracts of pristine forests. On top of all this, what used to be sustainable traditional hunting for meat has begun to sound the death knell for species already teetering on the brink. This poses a particularly serious threat in parts of Assam, central and eastern Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Tripura, the hill districts of Manipur, and throughout Nagaland and Mizoram. The Nyishis of Arunachal Pradesh also hunt primates for their pelt to fashion traditional dao-sheaths. What I witnessed in northern Sonitpur in Assam in the 1990s was unthinkable. A few hundred square kilometres of excellent forest habitat had been systematically destroyed within a short span and all the langurs (possibly numbering around 1,000) just vanished. Some were killed by predators, many by domestic dogs and the rest, by encroachers!

On Speciation

In India, capped langurs are found in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. Elsewhere, their range extends into southeastern Bhutan, eastern Bangladesh, northwestern Myanmar (west of the Chindwin river), and a small part of Tibet. Capped langurs range widely from floodplains to near the winter snowline, and geographic variations reveal minor physical changes, often seasonal, in the colour of their pelage. Based on these features, at least five subspecies or races were once recognised: pileatus, durga, brahma, tenebricus and shortridgei. The last named has since been upgraded to a full species by Prof. Colin Groves. Subsequently I synonimised the race durga with the nominate race, as listed in my book The Mammals of North East India (2013).

I have always felt that a fresh review is called for in light of these seasonal colour variations that I have observed closely in the wild, where two or even three races sometimes occupy the same area, often living as part of the same group.

Careful study and extensive photography have thrown up new insights that were once lost in the blur of the assumption that all capped langurs were uniform. A lifetime spent with these primates leads me to believe that their distinguishing features, especially facial hair patterns, clearly and consistently distinguish langurs that are resident north of the Brahmaputra river, from those to the south. Clearly this massive river has played a role as a major zoogeographic barrier. The turning point came in June 2013 when I closely observed troupes of two subspecies within a span of a few hours when many close-up images were taken by me. Days and weeks of careful study seemed to ratify my earlier belief in the reliability of colour-based separation of races.

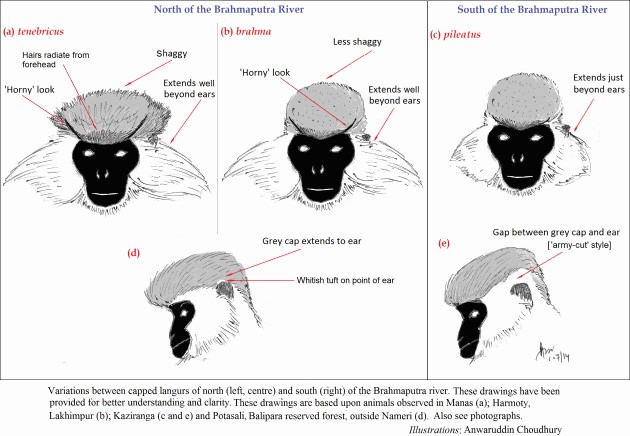

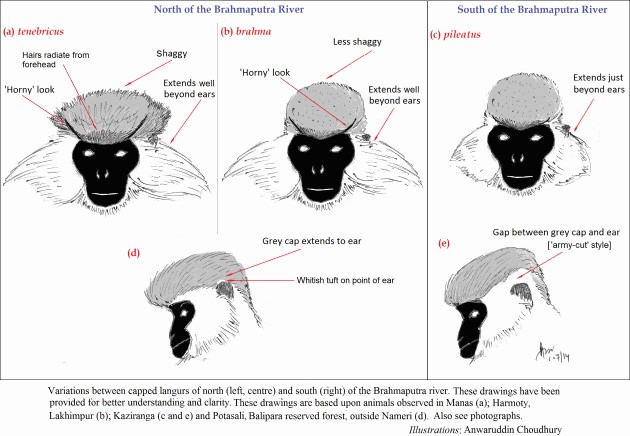

It turned out that the subspecies brahma and tenebricus, both found north of the Brahmaputra, have features in common, but which differ from the langurs south of the Brahmaputra. The Jia-Bhoroli (known as Kameng in Arunachal Pradesh) also presents an impassible barrier separating the two subspecies to the north of the river. The primary difference seems to lie in the pattern of the cap of brahma and also some differences in pelage, which still separate them from tenebricus. Capped langurs separated by the Brahmaputra river have distinctly different caps, whose contact with the ears is telling.

In capped langurs to the south of the Brahmaputra, the grey cap is separate, forming an ‘army-cut hairstyle’ in pileatus and durga (now synonymised as pileatus). As for the langurs restricted to forests north of the Brahmaputra, the darker grey cap extends to the ear in case of the races tenebricus and brahma (see illustration). The side-whiskers of tenebricus and brahma are also notably longer than those of pileatus. The key feature distinguishing tenebricus from brahma is the cap. In tenebricus it is shaggy, with hairs radiating away from the forehead. In brahma the cap is less shaggy and more of a pom-pom similar to that of pileatus, but with the grey cap extending down to the ears (not in pileatus).

In my view, the mere listing of Trachypithecus pileatus under Schedule I of the Wild Life (Protection) Act of India, despite it being the highest conservation status in India, is just not enough. This is because enforcement in the field is totally inadequate. In 2001, I actually saw two or three langur pelts on sale in a government sales depot belonging to the Industries Department at Seppa in East Kameng! The salesman was apparently unaware of the species and had no clue that the sale was illegal.

Although the capped langur is still widely distributed throughout Northeast India, there are many small and isolated populations on account of habitat fragmentation. Frankly many have little hope of survival in the mid-to-long-term, and local extinctions are a foregone conclusion. The monkeys have already been extirpated from the Manipur valley, the plains of Lakhimpur district, most of the tableland on the Meghalaya plateau, and parts of the Sonitpur district in Assam. Tragically the entire population of capped langurs, together with all other primates, has vanished from the 900 sq. km. rainforest tract comprising the Nambor (south block), Diphu, and Rengma Reserved Forests in Golaghat district of Assam because of the infamous border problems with Nagaland and the subsequent felling, poaching and encroachment of this once-rich tract.

How many capped langurs might be left? An exercise was carried out by me in Assam in the 1980s that estimated 39,000 individuals. A similar exercise between 2008 and 2014 in the same areas indicated 18,600 (range: 17,500–20,000) langurs. The writing is on the wall. A similar exercise was never carried out for all of Northeast India, but since the extent of forest is larger, and accessibility is relatively low, Arunachal Pradesh could harbour larger numbers than Assam. But with so many new dams in the offing, and the cry for ‘development’ ringing in the corridors of power, who knows?

Nothing can take away from the simplest of simple strategies if we wish to keep our biodiversity intact. Protect existing national parks and sanctuaries. Create more sacrosanct sanctuaries and national parks such as Dhansiri and Lumding in Assam, Satoi and Saramati in Nagaland, and the Inner Line forests of Mizoram. Simultaneously we need to recognise the wisdom of expanding and securing all existing Protected Areas. This means strict enforcement at the cost of popularity, and also initiatives such as the introduction of synthetic or cotton dao-sheaths (to replace capped langur skins) for the Nyishi tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. I have interacted with village chieftains and they all agreed that this would work.

It goes without saying, however, that we as a people must want to keep our wildlife and our pristine natural ecosystems alive. If this is not to be, then it is not just the capped langurs that will vanish.