The Bengal Slow Loris

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 4,

April 2017

By Swapna Nelaballi

We had been searching for over a week without any success. It dawned upon us that this chilly June night might not be any different. Dark clouds loomed above us. Yet, like every other night we had spent in the Trishna Wildlife Sanctuary, an area of about 195 sq. km. located in the southern part of the landlocked north-eastern hill state of Tripura, we couldn’t but be hopeful that we would look into the mesmerising, fiery red eyes of the elusive nocturnal creature that we sought. We had been trudging for hours along overgrown forest trails. As we showered light from forest floor to the canopy, spectacularly-coloured moths, glowing bugs, slithering serpents, mysterious leopard cats and seemingly-headless sleeping birds, made occasional appearances, keeping our senses alert.

My companions resorted to whistling Bollywood melodies and thunderous throat clearing to display their frustration. For my part, tired of repeating instructions to be silent, I began paying more attention to ridding myself of mosquitoes and clambering leeches. Suddenly, as is usually the way of the jungle, out of the darkness appeared the largest crimson eye shine I had ever seen. Forgetting all the rules I leapt into the air screaming, ‘Lajwanti banor! Lajwanti banor!’ (which means slow loris in the local language, Bangla) stunning the poor creature and the rest alike. Finally, there it was, all that I had been longing for – a slow loris and pin-drop silence. We gaped at the tiny ball of fur gaping back at us from the canopy for a wonderful 60 seconds before it made its way deeper into the foliage and out of our view. We went on to have eight more encounters during our short survey. They were brief, but important, as they fuelled in me a strong desire to learn more about the loris and its way of life.

Thus, began the first ecological study on the elusive Bengal slow loris Nycticebus bengalensis.

The Bengal slow loris can often be seen upside down, firmly anchored to a tree trunk while gouging for exudates. It is perfectly adapted for such a diet with unique grasping hands and strong hind limbs. Photo Courtesy: Swapna Nelaballi

Deep gouges created on the trunk of a Sterculia villosa allow the Bengal slow loris to obtain valuable exudates. The animals remember productive sites and visit them often. Photo Courtesy: Swapna Nelaballi

Uncovering a Secret Life

If the word ‘first’ comes as a surprise, let me then clarify that there is a paucity of knowledge on nocturnal primates. Nocturnal primates, especially the Lorisidae family to which the slow loris belongs, have received little attention worldwide. Among the slow lorises there are five recognised species and until recently most of them featured as data deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List (a comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of species). Four of the five species fall under the category ‘vulnerable’, while the fifth is ‘critically endangered’ and the population of all five is listed as declining. This is not surprising as these species face several threats across their range. Despite this, their ecology remains largely unknown. The only information on the Bengal slow loris despite its large geographic range spanning from Northeast India, Myanmar, Cambodia, southern China, Laos and Thailand to Vietnam, comes from observations in captivity, reconnaissance surveys and opportunistic sightings, which have served to merely provide information on occurrence.

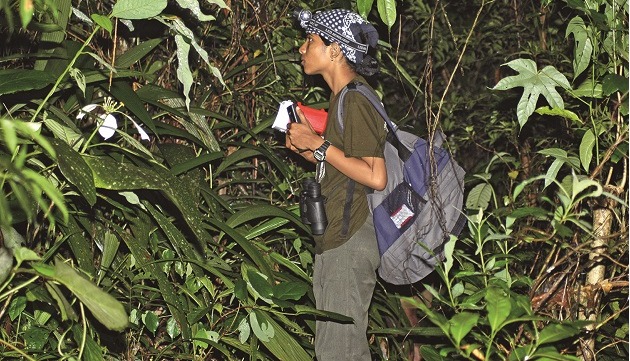

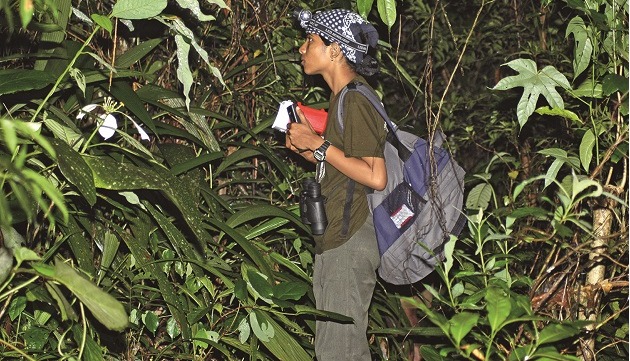

The author’s study on the Bengal slow loris was based in Tripura’s Trishna Wildlife Sanctuary. Habitat loss and capture to cater to the illegal, exotic pet trade combine to gravely threaten this arboreal primate. Photo Courtesy: Ramki Sreenivasan

Determined to change the picture (at least to some extent), I returned to Tripura and set out on my Masters’ degree dissertation project armed with scant information, heavy-duty headlamps, and my only experience of working at night – a one-and-a-half-month stint at a call centre. I studied their feeding behaviour across the cool, dry winter months of December, January and February and hot, humid summer months of March, April and May. Every minute of the six months that I spent following and studying slow lorises was an absolute delight.

I watched lorises navigate through leafy jungle, gouge out gums,

devour floral nectar, trap flying moths, steal bird eggs, sleep, groom, get stuck among climbers, fall off trees, almost head-butt a civet and be bitten by mosquitoes!

True Gougers

I also looked at their dietary habits, which is a vital conservation aspect in terms of habitat protection. I found that lorises spend nearly 85 per cent of their overall feeding time eating plant exudates such as gums and saps. Their diet was dominated by plant exudates even when the trees began to fruit and flower in the summer months and more floral nectar and fruits were available to them. Eating plant exudates can be challenging. Although they are rich in energy, they are knotted in long chains of polysaccharides and are often laced with toxic compounds, and never abundant.

The Bengal loris is, in fact, perfectly physically adapted for such a diet, literally from head to toe. Their unique grasping hands and strong hind limbs have evolved to hold on to tree trunks for extended periods of time. And while doing so, they gouge trees and scrape out gum with their incisors that are modified into toothcombs. Their long tongues help in lapping up sap from deeper tree wounds and their large intestines have a sizeable pouch (caecum) that helps breakdown complex exudates. Other slow loris species have similar adaptations, placing them amongst a select category of ‘true gougers’. This category includes primates ranging from marmosets and tamarins in South America, to lemurs from Madagascar.

The author spent six months studying slow lorises for her Masters’ degree dissertation project, designed to better understand the behaviour and food habits of the species. Photo Courtesy: Vicky Lakshman

Night after night, Bengal slow lorises followed the same foraging routes, going from one exudate site to another. They also visited the same exudate site more than once during the same night, indicative of their exudate harvesting capabilities. Exudate trees, often riddled with hundreds of gouged holes, may be characterised as patchily distributed, clumped resources. Thus, once a loris locates a valuable exudate site, it is well remembered and revisited time and again.

So what were these plant species that were remembered and revisited? I discovered that lorises didn’t use all plant species equally. Of the 73 plant species I recorded in vegetation plots, they selectively fed from 10, and this varied from one season to another. Among the 10, a substantial proportion of feeding occurred only on a couple of species. They not only spent most of their time feeding on few species but preferentially selected certain individual trees of those species! I am yet to know the basis of this choice, but perhaps they chose certain trees based on their chemical composition, moisture content, and productivity.

This extreme selectivity for individual plants can be a problem when people target the same plant species. This is especially of concern in states such as Tripura, where all that remains are fragmented forests, which also house several marginalised forest-dependent human communities. Understandably, apart from economic and subsistence values, seldom are other values attached to natural resources. Thus, anthropogenic pressures are unfortunately extremely high.

Threats to Survival

While most primates are indisputably affected by habitat loss, a more serious threat to this species in particular is the extremely lucrative illegal wildlife trade. Slow lorises are one of the most commonly-seen primate species in markets across their range to meet the demand for the species as pets. This extensive trade resulted in slow lorises being moved from Appendix II (where international trade is regulated and monitored) to Appendix I (all international trade is banned) of the CITES in 2007. A thriving trade exists not only in local markets across Southeast Asia but also over the Internet, where illegally-acquired slow lorises feature in some of the most-viewed ‘viral’ videos. While enforcement authorities can use the Internet as a tool to monitor and police some of the trade, there are markedly greater negative ramifications. These videos portraying a round-faced, large-eyed, fuzzy-furred, docile and seemingly friendly pet are highly misleading given what we know of their ecology and behaviour. Such imagery elicits a strong desire to acquire similar pets among uninformed potential buyers and is a matter of grave concern.

Even more troublesome, these highly-specialised primates are known to fare poorly in captivity, even at well-informed breeding centres, where they show low mating success and high levels of aggression toward one another. Yet, lorises are commonly seen packed by the dozen into unventilated bins or cages at noisy, bustling, dusty and hot markets. To make them more ‘people-friendly’, their specialised toothcombs and molars are inhumanely extracted using pliers without anaesthesia. An unknown number of animals die before they are traded - from blood loss and infection due to tooth extractions, from toxic bites obtained from other lorises housed in these cramped spaces, and yet more from unhygienic conditions, unsuitable diets, dehydration, transport stress, and manhandling. The few that survive these torture chambers are then shipped far and wide, destined to live in brightly lit homes, to be fed on boiled rice or bananas and to be tickled until their deaths.

As a nocturnal primate, loris eyes are not adapted for continued exposure to bright light, and are severely damaged by a diurnal lifestyle. Their natural defence to freeze or raise their arms when threatened is often misconstrued as an invitation to be petted. Slow lorises in the wild lift their arms to mix a secretion from a gland near their elbow with their saliva before rendering a toxic bite in defence. Finally, provisioning them with an appropriate diet is difficult. Even well-informed rescue/rehabilitation centres find it a difficult task to provide slow lorises with an appropriate diet given their specialised requirements and the sheer paucity of information from the wild, let alone trying to match these requirements at someone’s home. Even if one were to try, given that the specialised teeth required for their special diet have been removed makes this impossible. In the wild, lorises range far and wide to fulfil their nutritional requirements, thus the physiological and psychological stress of prolonged solitary confinement is unimaginable.

Another serious consideration is their notoriously-slow reproductive rates. Even among primates, they have far fewer offspring in their lifetime for their body size. This is because they take comparatively longer to reach sexual maturity and they have long inter-birth intervals with prolonged periods of parental care. Considering the large number of individuals that are most likely extracted from the wild to ensure at least a few make it into homes as pets, population densities are, without doubt, dramatically impacted. Add to this the effects of widespread and rapid deforestation that is significantly reducing available habitat giving little or no chance for populations to recover.

Today, the Bengal slow loris, one of our most primitive ancestors, is trying to hold on. I realise that those who do not seem to share my fascination with this creature (and thus despair at their current plight) may have not had the good fortune to experience what I did. Rachel Carson eloquently stated: “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.” This is a small attempt to share that sense of wonder when I first saw the red eyes of a slow loris and then went on to discover its fascinating life in the wild.