Stories of Human Wildlife Relationships from the Eastern Himalaya

First published on

December 08, 2022

By Manisha Kumari, Pemba Tsering Romo and Dechin Pema Saingmo

The journey begins

As part of WWF-India’s conservation programme that aims to reduce the economic losses local communities incur due to human-wildlife conflicts over livestock loss, we set out in February 2022 to examine the nature and extent of Human-Wildlife Conflicts (HWC) in snow leopard habitats of West Kameng and Tawang districts.

We travelled across western Arunachal Pradesh for 45 days, visiting villages, meeting Brokpas (yak and dzomo herders from the Monpa region), GBs (Gaon Burahs – village headmen) and other key resource people to collect stories of human-wildlife interactions. The villages were in the region stretching from Jemeithang valley in the east to Mago valley in the west, Tawang monastery in the north to Chander village in the south. The 15 villages were Kharman-Kyalengteng, Socksten, Mago, Thingbu, Luguthang, Jang, Jangda, Rho, Seru, Mukto, Tawang monastery, Sengedzong, Nyukmadung, Lubrang and Chander.

_1670499447.jpg)

Alpine and mixed coniferous forests dominate Tawang, which is home to the snow leopard, musk deer and Asiatic black bear. Photo: Pemba Romo

Brokpas migrate seasonally in summer in search of pastures for their livestock. They cross village and international boundaries 3,000 m. above sea level and are continuously on the move for five to six months in a year.

New learnings at every turn

Reaching the villages was not easy – the roads were covered with snow and streams, making them treacherous and harsh; however, the mesmerising monsoon landscape of rhododendrons made the journey worthwhile.

Most people we met were positive and had a welcoming attitude. In some villages, especially those relatively new to interactions with Community Based Organisations and NGOs, people were apprehensive about meeting outsiders seeking information. For example, sharing livestock (yak and dzomo) numbers is often difficult for Brokpas because they pay taxes to their own village and neighbouring villages based on these numbers. These taxes are paid in cash and kind (ghee (clarified butter), chhurpi (local cheese), chir pine leaves, livestock) to the village councils.

To overcome the language barrier, a local guide acted as our translator. We would try to break the ice by interacting with village leaders first, explaining our work and snow balling to meet Brokpa families. We were patient and took an effort to understand and interact respectfully, which helped us gain their trust.

_1670499505.jpg)

Pemba and Dechin interviewing Brokpas of Jemeithang valley. Photo: Pemba Romo

For a gentle start, we began our tour from Jemeithang, as two of our teammates Pemba and Dechin hail from there. We wanted to collect information on human-wildlife conflict: the overall frequency and nature of livestock depredation, people’s perception towards snow leopards and dhole, types of conflict, conflict management measures and major issues related to livestock herding. Apart from this, we also tried to collect information on the history of the Brokpa villages, the migration route of Brokpas and the socio-cultural significance of their livelihood.

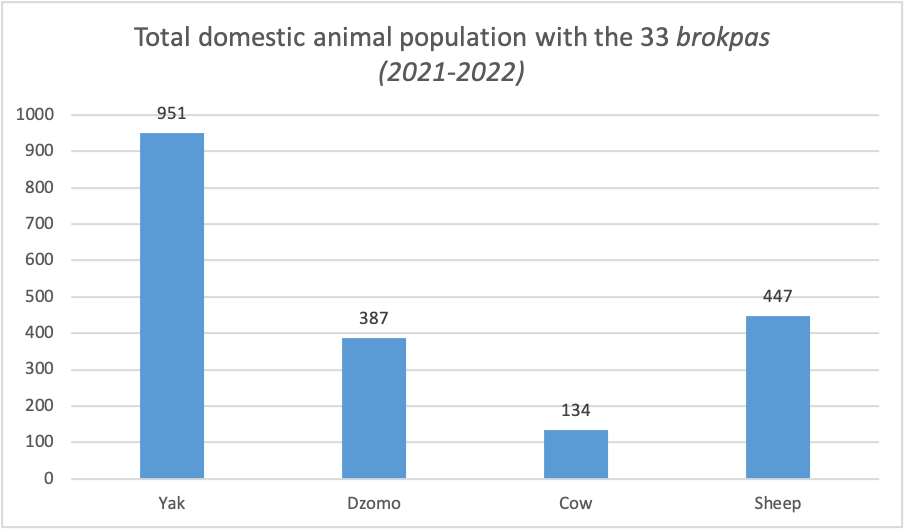

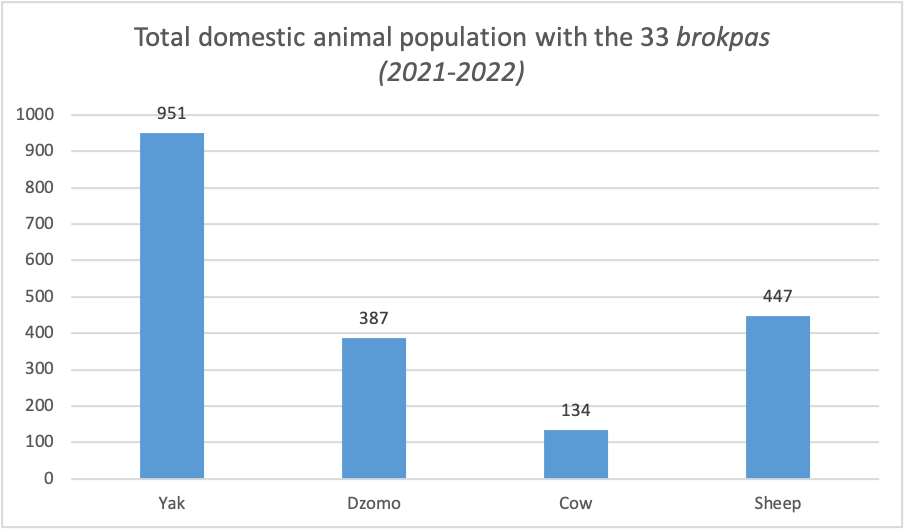

Human-wildlife conflict in the Eastern Himalaya

We interviewed 12 village leaders and 33 Brokpas. They had a total yak population of 951; and dzomo, cow, and sheep populations of 387, 134 and 447 respectively. The villages of Mago, Thingbu, and Luguthang had the highest number of yaks owned by a Brokpa family. The number of yak owned by a Brokpa family can vary from one to more than 100. Families with a few yak or even many frequently leave them in the care of other families.

_1670499628.JPG)

Grazing grounds for yak in eastern Tawang. Photo: Manisha Kumari

The Brokpas revealed the different reasons for livestock deaths in the Eastern Himalaya. Most of the villagers told us about livestock diseases that cause heavy casualties every year. The major health concerns for livestock in these areas are diarrhoea, malaria, tick, flea and mite infection, dehydration, and death due to dirty water consumption.

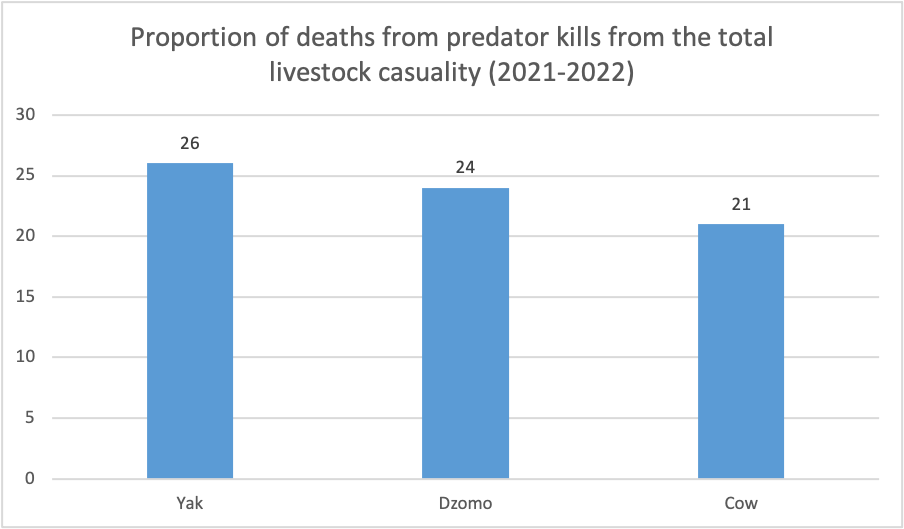

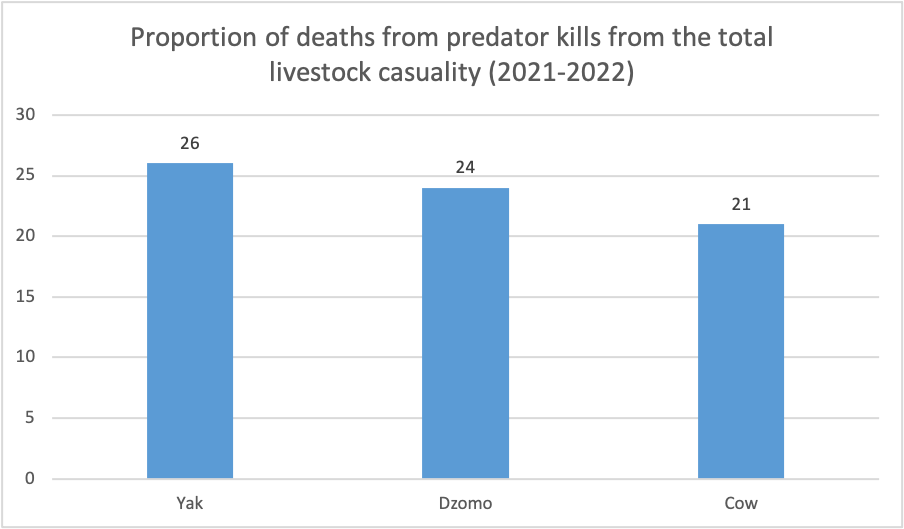

From our assessment we found that in 2021-2022, the largest proportion of deaths in the yak, cow and dzomo populations were caused by diseases, followed by predator attacks. Dhole and snow leopard attacks were responsible for 26 per cent of the total yak deaths in these 15 villages. Dzomo and cow figures were also comparable at 24 per cent and 21 per cent respectively. Other reasons for fatalities were from natural calamities (excessive heat or cold) and accidents. Interestingly, seventy-seven per cent of the total livestock (yak, dzomo and cow) deaths by predator kills were of calves. Calves are more susceptible to predators because of their inability to defend themselves.

_1670499708.jpg)

Seventy-seven per cent of the total livestock (yak, dzomo and cow only) deaths by predator kills were of calves, which are more vulnerable to attacks from dhole and snow leopards. Photo: Manisha Kumari

We attempted to probe a little more into the nature of these predator attacks. All the Brokpas said that dhole cause the highest casualties and are the main predators responsible for livestock kills, followed by snow leopards and Asiatic black bears. Dhole kills are generally during the day. Calves are usually kept inside makeshift bamboo enclosures present at camping sites in the grazing grounds. Brokpas change their location often to reach different grazing grounds. However, even if confined to a single grazing area, it is difficult for a Brokpa to keep watch over tens of livestock grazing freely across acres of land. They even take help from the lama (religious leaders) – they perform rituals and receive gau (a Tibetan amulet) for their livestock. Some Brokpas also use fire to clear forests around grazing grounds for better visibility of wildlife to prevent predator kills. A few Brokpas also engage in retaliatory killings of dhole and snow leopards, such as killing cubs of these predators, carcass poisoning, and rewarding hunters/Brokpas who have killed them.

We found that huge livestock losses due to predator kills have created a negative perception of the dhole. The reaction of Brokpas towards snow leopards was mixed, with most of them having no feelings (angry or happy) towards them. But still, a majority of them considered the presence of snow leopards in their forests a good sign. This was not the case for dholes. There was also a glimmer of faith in their perception towards dhole; few villages believe the dhole is the protector of their deity, and keeping the fireplace in grazing huts unclean angers the deity, which causes dhole to attack their livestock. It was interesting to know that Brokpas knew a few things about the dhole, for instance that it lives and hunts in packs. This can be linked to high encounter rates with dhole compared to almost none with snow leopards.

_1670499812.jpg)

Talking to Brokpas of Tawang revealed the dhole as the major conflict animal, followed by the snow leopard. Photo: Manisha Kumari

Exploring innovative solutions

It is essential to explore measures to offset the cost of livestock depredation. The Department of Animal Husbandry, Veterinary and Dairy Development has been strongly promoting cattle vaccination and insurance in the landscape. Despite hesitation in accepting cattle vaccination, the department has been successful in gradually improving the number of livestock vaccinated. There are a few instances in which Brokpas working in the department have insured their livestock. However, in the villages we visited, the Brokpas or village leaders didn’t know how to avail the insurance and many were unaware of its purpose. This highlights the need to create greater awareness about the scheme and its benefits. It is very difficult to completely meet the costs incurred from livestock loss, but every effort towards the same can be helpful for the Brokpas.

WWF-India, with support from WWF-UK and Pureplay, has been exploring innovative solutions to address livestock depredation. While providing compensation is a common way to mitigate the impact of predator kills, WWF-India is focusing on bringing more preventive measures to address the issue. Apart from organising cattle health camps in partnership with the department and NRC-Yak Dirang; the WWF-India team is piloting the use of fox lights with a few Brokpa families. Fox lights are solar powered LED lights that flash with three bright colours projecting in 360 degrees and visible from one kilometre. This non-lethal method to control predators at night has been implemented across the globe and in India. As this is the first time they are being used in the high-altitude terrain of the Eastern Himalaya, WWF-India distributed six fox lights in Thingbu in Tawang to test their effectiveness. There are six grazing routes in Thingbu and each is used by five to six families. One fox light was disseminated to a Brokpa family of the designated grazing route elected in the community meeting. All families were taught how to handle and use the fox light so it could be shared. The team also collected data on the number of deaths from predator kills along every grazing route. This would be required to assess the success of fox lights. The Brokpas have been taking the lights with them during the summer migration, which began from June.

Explaining the use of fox lights to the Brokpas of Thingbu village. Photo: Dechin Saingmo

More creative solutions like these needs to be explored in Arunachal Pradesh. While the state has seen an increase in the yak population since 2012 and has more than 40 per cent of India’s total yak population, the number of Brokpa families has been decreasing gradually, threatening the long-term sustainability of this livelihood. Yak herding and its products are associated with Monpa food, culture and identity.

Human-wildlife conflict is not only causing huge economic losses but also leading to negative perceptions towards wildlife. More efforts need to be undertaken to understand the complexities attached to such changes in attitudes. Addressing HWC will not only reduce negative impacts but will also help in protecting high altitude habitats and the vulnerable species that call it home.

Manisha Kumari is a Senior Project Officer at the Western Arunachal Landscape team of WWF-India. She is a researcher working on strengthening community-based conservation initiatives, natural resource management, forest-based livelihoods and conservation education.

Dechin Pema Saingmo and Pemba Tsering Romo have been working with WWF-India as research assistants. With the support of Sanctuary's Mud on Boots Project, they are helping develop strategies for the long-term conservation of snow leopards and other high-altitude wildlife of Mago-chu valley in Arunachal Pradesh. Both of them are alumni of Green Hub, a video-documentation centre in Tezpur, Assam. Dechin and Pemba intend to use their photo and video documentation skills to record the flora and fauna of their home valley and use it to advocate for biodiversity conservation in the region.

_1670499447.jpg)

_1670499505.jpg)

_1670499708.jpg)

_1670499812.jpg)