State vs Elephas Maximus

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 38

No. 12,

December 2018

By Cara Tejpal

Status of Asian Elephants in India

India holds the largest population of wild Asian elephants in the world and in 2010, the Indian elephant Elephas maximus indicus was declared the country’s National Heritage Animal. An estimated 27,000 individuals survive in less than two per cent of the country’s geographical area and there is a declining trend in this population, according to a government report from 2017. Asian elephants are globally endangered and come under Schedule I of India’s Wild Life Protection Act, 1972, which accords them the highest degree of protection available to a wild animal species. Elephants are wide-ranging, herd-living mammals but their habitats are under duress, with 72 of the documented 88 elephant corridors in the country having national highways, roads or railway lines slicing through them. To compound matters, elephant reserves have no legal sanctity and a measly 22 per cent of elephant habitats fall under India’s Protected Area network. Consequently, there has been a tragic rise in human-elephant conflict, and mitigation measures have, for the most part, been kneejerk reactions – unscientific and inadequate. Death by poisoning, electrocution, starvation or under the wheels of a train/vehicle are now commonplace occurences.

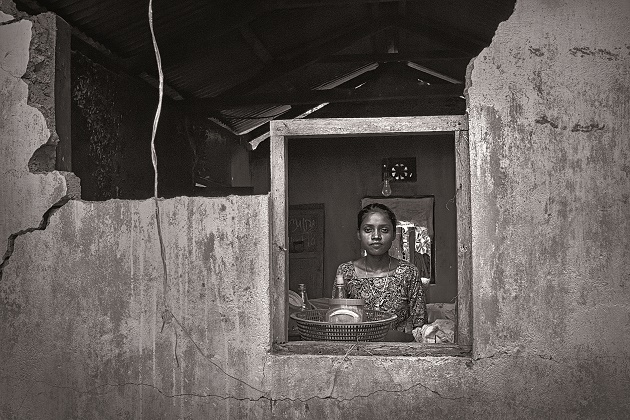

A wild elephant entered Mysuru city in the wee hours of the morning, panicking citizens and killing one. The terrified pachyderm was then tranquilised and carted off to the Bandipur National Park. Photo courtesy: Nagesh Panathale

Who Are the Petitioners?

There are three petitioners in this case.

Prerna Singh Bindra: The primary petitioner is an award-winning wildlife conservationist and writer. She has served as an independent member on the Standing Committee of India’s National Board for Wildlife and been on Uttarakhand’s State Board for Wildlife. In her capacity as a journalist, Bindra has written innumerable hard-hitting conservation reports and is the author of three books, including the recently-published non-fiction chronicle of India’s wildlife crisis, The Vanishing (see "Book Review: The Vanishing" of this December Issue).

Priyanka Bala Rajaram: A student pursuing a Bachelors degree in law from Queen Mary University of London, Rajaram is interested in social work and volunteers her time and skills to various causes.

Pallavi Bala Rajaram: A passionate advocate for animal rights and welfare, Rajaram actively assists various NGOs and government bodies on projects initiated in the interest of the differently abled and economically challenged sections of society.

Who Are the Respondents?

There are currently five respondents that have been named in the PIL.

The primary respondent is the Union of India, through the Secretary of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). The MoEFCC is the nodal agency of the central government for the planning and implementation of India’s environment programmes and policies.

The other four respondents are the states of Karnataka, West Bengal, Jharkhand and Odisha through their respective Principle Chief Conservators of Forest.

Madhya Pradesh Too?

The traumatic capture of a herd of five wild elephants, including a calf, that ventured into the Sidhi district of Madhya Pradesh from neighbouring Chhattisgarh in September 2018 has made M.P. a hot contender to be included in the list of respondents to the PIL. Tragically, the young calf died the day after the ordeal, though the reason for death has not been ascertained. The four adult elephants are now doomed to a life in captivity, ferrying tourists around the Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve. This herd had not caused any damage, but merely crossed state borders.

Key Claims

The petitioners have accused the respondents of “appalling, heart-wrenching acts being undertaken by the Forest Departments…”, going against their “moral and legal mandate to prevent the infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering on animals…” and for “adopting brutal methods which harm, injure and even kill wild animals in the name of wildlife conservation”.

Karnataka has been called out for frittering huge sums of money on the installation of crude metal spikes on the forest floor and boundary walls to restrict the movement of elephants.

Barbaric ‘anti-elephant’ metal spikes installed on forest floors in Karnataka are known to grievously injure animals. Photo Courtesy: Divya Vasudev

These rusty spikes can both injure and kill wild animals and incidents of blood being found on these installations have been recorded. Such an intervention has not been supported by any scientific or expert recommendation as revealed by an RTI application.

West Bengal has been listed as a respondent for supporting and deploying hulla parties to chase elephants. Hulla parties essentially comprise mobs of men brandishing oil-soaked, burning gunny sacks tied to wooden sticks or metal rods. Elephants that venture out of desired areas have these lit gunny bags flung at them and are harassed and chased by the mob in unregulated scenes of complete chaos. Members of these hulla parties are usually employed on a daily-wage basis from local villages and receive no training, sensitisation or orientation for their own or the animals’ safety. Both humans and elephants have died as a result of this ill-advised intervention measure. Though the PCCF of the state issued a directive againt hulla parties in 2016, the practice continues.

A hulla party comprising mobs of men brandishing oil-soaked, burning gunny sacks tied to wooden sticks and metal rods is photographed chasing a herd of elephants in Bankura, West Bengal. Elephants that venture out of desired areas have these lit gunny bags flung at them and are harassed in unregulated scenes of complete chaos. Photo courtesy: Biplap Hazra

Odisha and Jharkhand are named in the PIL for their knee-jerk strategy of chasing wild elephants across state borders with a bizarre “not my state, not my problem” attitude. Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Goa and Madhya Pradesh are also known to indulge in such ill-advised actions. The traditional migratory routes of herds in central-eastern India have been obstructed by barriers, barbed wire and trenches along the Bengal, Odisha and Jharkhand borders, leaving them stranded in human-dominated landscapes.

The acts described and denounced by the petitioners contradict the spirit of the Constitution of India, and are in contravention of the Wild Life Protection Act (1972), and the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (1960).

The Vision

“The elephant in the room – literally – is the relentless destruction and fragmentation of habitat, squeezing these gentle giants into small islands,” explains Bindra in The Vanishing. “… What is the elephant to do, where does it go, what does it eat, with humans having flattened and invaded its forests?” she asks.

The vision that Bindra has for this PIL is not just the cessation of illegal activities by the mentioned Forest Departments, but also formulating strict retributive action for activities that are detrimental to wildlife, the deployment of public participatory methods for conflict mitigation, the implementation of scientifically-sound mitigation measures and, most importantly, the prevention of further fragmentation of elephant habitats. Toward this end, she recommends the declaration of all elephant reserves and corridors as Eco Sensitive Zones, with all proposed development projects in these areas coming under the ambit of the NBWL. She also suggests that each state draft a master plan that identifies elephant habitats outside Protected Areas and allocate funds to acquire these in a time-bound and strategic manner.

Sanctuary’s Take

It is crystal clear that neither the central government nor elephant-range states have taken cognisance of the desperate status of wild elephants in India. Central programmes such as Project Elephant have provided little more than lip service and the commissioning of reports, and state Forest Departments have been left to their own devices to tackle the escalating conflict.

It is particularly distressing that despite being home to some of the world’s foremost authorities on Asian elephants and a battalion of razor-sharp scientists, the Indian government has failed to formulate customised strategies for conflict mitigation in each elephant-range state, while continuing to allow the devastation of the country’s forests. Further, the capture of wild elephants for commercial use is an outdated practice and the deployment of CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority) funds for the purchase and trading of elephants for tourism flirts with illegality.

The respondents to this PIL are not the only states that are guilty of criminal neglect/action when it comes to human-elephant conflict. Sanctuary has recently alerted the environment ministry to the human-elephant conflict crisis in Chhattisgarh and is aware of rising conflict in other states as well.

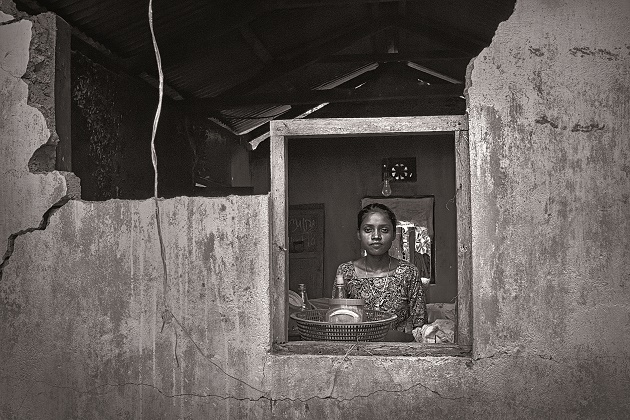

A tea garden labourer from Hantupara, Assam, stands in the window of her broken house, which was damaged by an elephant, as she awaits acknowledgement of the conflict from the tea garden authority. Photo Courtesy: Avijan Saha

The valiant and occasionally successful conservation efforts of individuals and NGOs must be applauded, but in the long run they will prove toothless without the backing of the state. This PIL initiated by the three petitioners should serve as a jarring wake-up call to the country, and deserves wide public support. It is in the interest of both elephants and the thousands of humans who are bearing the tragic brunt of the conflict.

Author: Cara Tejpal