Sinharaja - The Heart Of South Asian Biodiversity

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 4,

April 2020

Text, Photographs and Maps by Ian Lockwood

It is early morning in the heart of the forest, a resplendent South Asian tropical rainforest in Sri Lanka, and I am mesmerised by the richness of life around me. Towering dipterocarp trees rise from a thicket of lianas, tree ferns and spiked rattan climbers. The branches of the trees are dripping with epiphytes and the remains of a morning shower. I breathe in the dampness and the rich scent of decomposing leaf litter. A cacophony of a mixed species feeding flock is approaching with a pair of normally reclusive Red-faced Malkohas Phaenicophaeus pyrrhocephalus leading the frenzy. A short while ago, a small group of us was spellbound by a Sri Lanka green pitviper Trimeresurus trigonocephalus that was perched motionless over a rivulet. The deep calls of purple-faced langurs Semnopithecus vetulus vetulus, recently split from other similar primates, are reverberating from the canopy. And yet, none of this was here 50 years ago when the very same region was being aggressively logged for the short-term gains of manufacturing plywood. From a ravaged landscape to being a world heritage site and one of Asia’s premier rainforests, this is the remarkable legacy of Sinharaja (Sanctuary Vol. 2 No. 3, July/September 1982).

Part of what has made Sinharaja so successful is that visitors interested in the experience must forsake ideas of speed and quick gratification. In Sinharaja, a visitor does not rush; for when one does, they miss what makes it so special. The beauty of the rainforest must be experienced slowly, on foot and under one’s own steam. There are few guarantees on what you see and so each visit offers an opportunity for a new personal discovery. Of course, there are nuisances like leeches, frequent rain showers, rough trails and damp conditions. Serendipity, the idea of unexpected good fortune, so associated with the island of Sri Lanka, is modus operandi on the trails of Sinharaja.

(B_W)(01_17)_C-1700_1631873105.jpg)

The distinction between Sinharaja’s primary and secondary forest types is unrecognisable after several decades of protection, recovery and restoration. The ridge forest in this panoramic image was never logged but the valley’s trees were felled in the early 1970s.

Sri Lanka’s three principal mountainous areas – the Knuckles, Central Highlands and Rakwana Hills – were isolated from destructive land uses until the rise of European colonial rule. Areas in Sri Lanka’s wet zone located in the southwest of the country still host relic plants, birds, and animals that had very ancient affinities – some even stretching back to Gondwanaland. The biogeography of these species and how they are linked to Madagascar, South India and Southeast Asia is a fascinating story that is only now just being better understood.

(12_18)_C-1700_1631873222.jpg)

Students on a birdwatching and adventure course cross a stream fed by Sinharaja’s forest. Ecotourism has played an important and largely positive role in the conservation success of Sinharaja.

BIRDWATCHING AT THE FORE

There is a long history of visitors from afar being drawn to Taprobane or Ceylon as Sri Lanka was known earlier. Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta, and Mark Twain all wrote glowing descriptions and just last year the island was ranked by Lonely Planet as the “World’s #1 travel destination.” Beyond the beaches and ancient cities of the cultural triangle, Sri Lanka has a special pull on wildlife tourists. Generally speaking, these individuals are attracted by the large charismatic species, namely the leopards and herds of elephants in the grand Protected Areas of Yala, Minneriya and Wilpattu. Those are worthy parks, albeit a bit over-visited and crowded with vehicular traffic. The visitor’s experience in Sinharaja is quite different and the site offers a different model for conservation.'

Creatures with wings are what brought Sinharaja into focus amongst conservationists and wildlife enthusiasts on a national, regional and now global scale. From being a specialised destination that was hard to get to, Sinharaja is now a premier birdwatching site that is visited by thousands of visitors spread over 12 months. The growth of Sinharaja as a top birding site has been organic as it evolved from being a recovering forest to a long-term research site and now a destination for birders and other ecotourists.

_C-1700_1631873473.jpg)

A home garden in the shadow of Sinharaja’s northwestern boundary near Kudawa. Some of Sinharaja’s best birding can be experienced in areas between protected forest and home gardens.

Sinharaja’s tourists buy entrance tickets from the Forest Department and many stay in locally-run homestays located in or near the buffer zone. Martin Wijesinghe’s Forest Lodge on the Kudawa entrance side of Sinharaja was the first place to cater to birders. With the support of friends in Colombo University, Martin has played a pivotal role in promoting birdwatching (and thus ecotourism) in Sinharaja and his approach has been mimicked by numerous other places.

Serious birders are in Sinharaja to see, photograph and/or tick off as many of Sri Lanka’s 33 endemic bird species. They walk, rather than drive, in fossil fuel-powered vehicles, to experience the rainforest. Each group entering the forest from the two principal entrances is required to take a local guide. These men and women are recruited from neighbouring villages and undergo training with the Forest Department. While there are veterans with over 20 years’ experience amongst them, Sinharaja’s guides include young, energetic members in the team. The result is that these are highly sought-after positions and families living in the vicinity of the park entrances have become stakeholders in the success of the Protected Area.

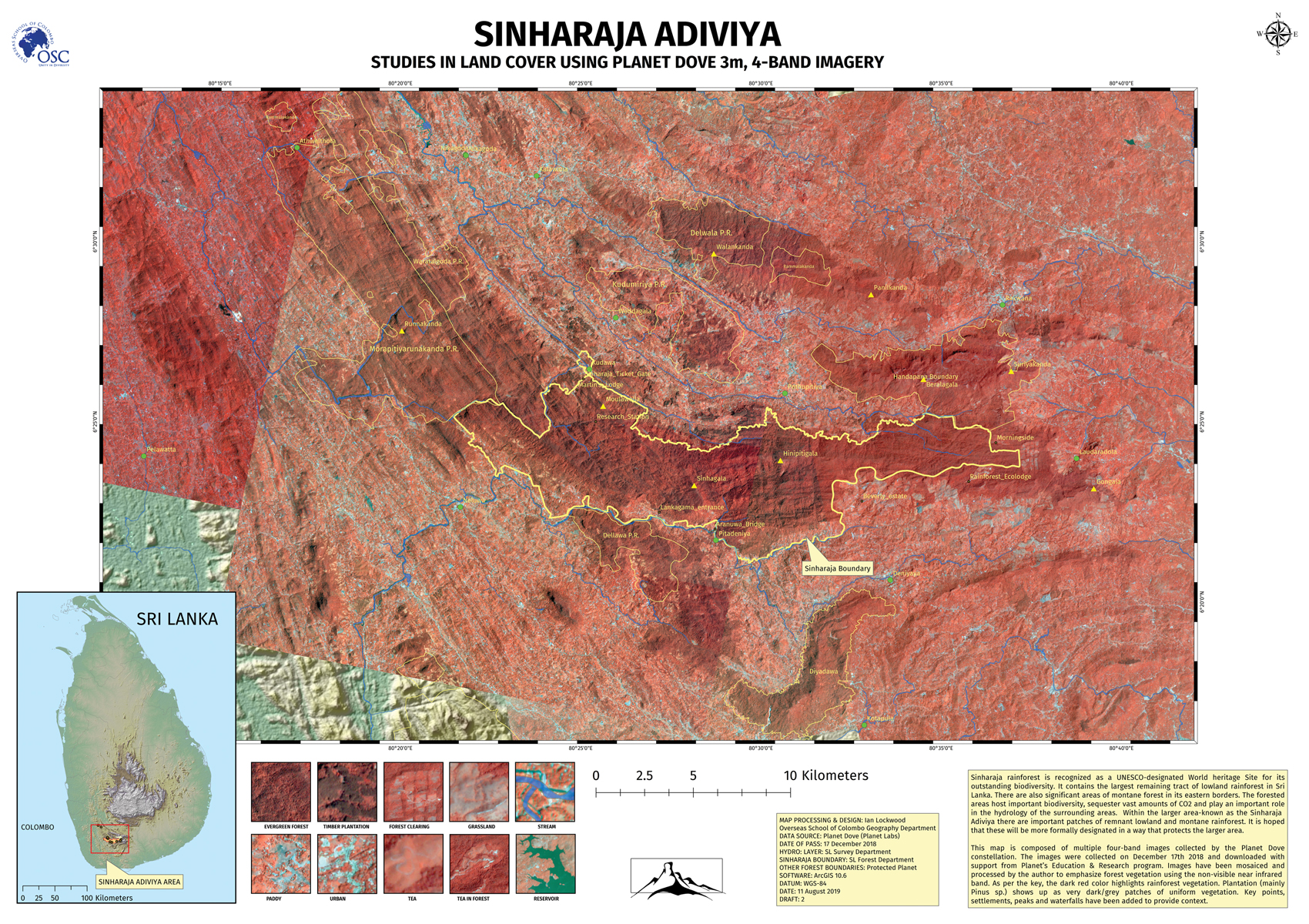

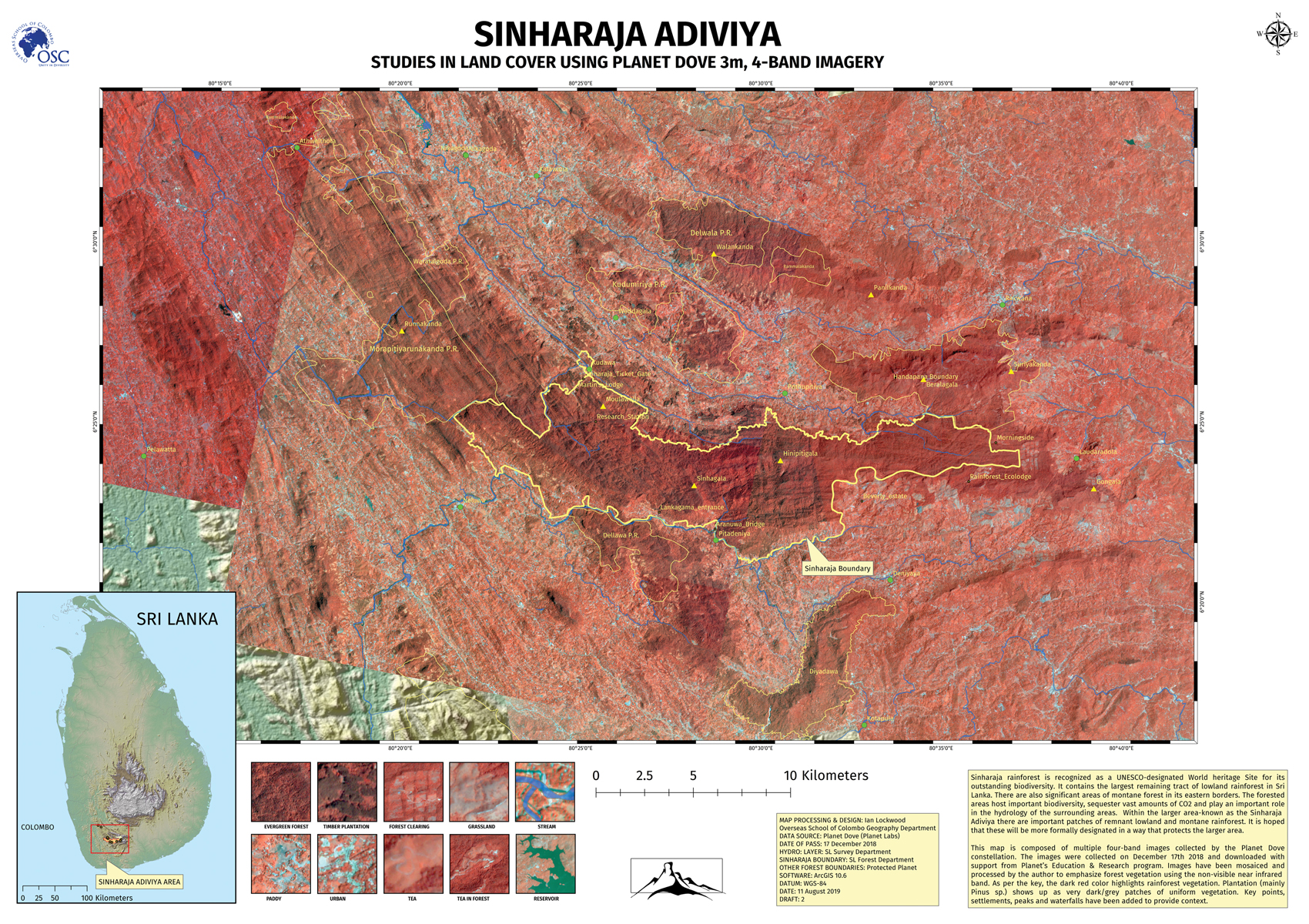

-Sinharaja-Index-Map-(2019_04)_C-1700_1631873685.jpg)

SHARED LESSONS

There are fascinating parallels in Sinharaja and Silent Valley in Kerala that are worth highlighting. Both have recent histories that started in controversy, elicited a ground swelling of public support and resulted in their protection. Both Protected Areas demonstrate effective management strategies. Silent Valley is blessed with a team of enthusiastic and committed personnel who love what they do. This stretches from the top level, who are more often in the field than office, to the forest guards manning remote posts. The Kerala Wildlife Department runs a tight operation and on a visit a few years ago, I was impressed by the commitment and love for their rainforest that they espoused. In Sinharaja, a similar pride in the Protected Area is evident in the forest guides that take tourists along trails at the Kudawa and Deniyaya entrances. Their livelihoods are closely connected to the protected forest. Ecological succession is happening in both places and the recovery of the rainforest is remarkable. There have been important studies conducted on this recovery as well as other aspects of the forest areas but there are opportunities to delve deeper. Both case studies demonstrate the power of protecting South Asian rainforests for ecological, aesthetic and even economic reasons.

EXPLOITATION, AWARENESS & PROTECTION

Sinharaja’s status as a Protected Area has mythological origins, but the modern site was born from controversy and exploitation. The lore associated with the forest stretches back to a time before recorded history. There are stories of a lion king living in the forest and the name Sinharaja evokes a sense of great pride amongst the Sinhalese. In the 19th and 20th centuries, much of Sri Lanka’s mountainous areas were converted into plantation agriculture and human populations surged southwest of the island. The Rakwana Hills and the area that is known as the Sinharaja Adiviya was an exception and enjoyed natural protection because of the rugged topography of its boundaries. However, in the 1960s, roads were built into the heart of Sinharaja for the first time. Mechanical logging was started to feed a large plywood mill located in the town of Avissawella. It was a time when this sort of project elicited praise for improving the prospect for “development.” Awareness about ecological matters – concepts like biodiversity, deforestation, ecosystem services and watershed management – were not in the public discourse of the age. Sinharaja’s living creatures, which were hardly catalogued at this stage, seemed to be on a course to destruction.

(09_19)_C-1700_1631874498.jpg)

The Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni was discovered by Sri Lankan ornithologist Deepal Warakagoda as recently as 2001. It is an endemic species found in the southern rainforests of Sri Lanka.

The 1970s were a time of uncertainty, being a period of political and economic turmoil across the world and in Sri Lanka. The nationalisation of private estates, the JVP insurrection and its forceful suppression as well as the simmering but soon-to-boil-over conflict with Tamils and their position in Sri Lankan society set the stage for uncertain times and tensions. Amongst all this, environmental movements began from nascent sparks. Groups of citizens, university professors and students started to raise awareness about the deforestation and the need to protect the Sinharaja forest. The March for Conservation group was a key player in raising public awareness. They recognised the area to be one of exceptional biodiversity (a term that was not widely used yet). It took politicisation of the issue and Julius Jayewardene’s 1977 election for that to happen. The logging soon stopped and Sinharaja was protected first as a sanctuary in 1978 and then as a UNESCO-designated World Heritage site in 1988. Responsibility for its protection went to the Forest Department rather than the Department of Wildlife Conservation. Since then, Sinharaja has become one of the most studied rainforests in Asia. The Smithsonian Institute and Yale University collaborated with Peradeniya University to launch a forest dynamics plot study where they studied 25 hectares of Sinharaja’s lowland rainforest in great detail over the course of several decades. Numerous studies of bird species have been conducted and published in a host of reputable scientific journals. Colombo University’s Zoology Department, Professor Sarath Kotagama and the affiliated Field Ornithology Department (FOGSL) were key players in this.

(05_18)_C-1700_1631874637.jpg)

The call of the endemic Sri Lanka Grey Hornbill Ocyceros gingalensis is unmistakable – it emits a series of clucks that gradually develop into what sounds like manic laughter.

(02_18)_C-1700_1631874740.jpg)

The resplendent Sri Lanka Blue Magpie Urocissa ornata is an endemic species that birdwatchers often seek in Sinharaja. It is restricted to lowland and montane evergreen forests in Sri Lanka’s wet zone.

RECOVERY & RESTORATION

Interestingly, the logged areas at the heart of Sinharaja experienced very little formal restoration efforts. Rather, the area was left alone and the neighbouring species were able to successfully recolonise the degraded slopes and valleys. Cleared forest areas are often vulnerable to invasion by fast growing non-native species. This happened to some extent, but native species were more successful in recolonisation. Visitors experience these areas as the “secondary forests” that line the old logging road (now a broken track that is difficult to walk on and impossible to drive on). When I first started visiting Sinharaja in 1999, the secondary forests were easy to identify with their thickets of growth and tall Calamus vines reaching up to the canopy. Today, the girth of the trees has increased, the Calamus is dying again and processes of ecological succession have taken these areas closer to climax vegetation. Nearby primary forest – areas that were never logged – are still distinguished by their climax species. That includes large buttressed trees like Shorea trapezifolia and Mesua nagassarium as well as a relatively less-crowded understory (simply because relatively little light reaches the forest floor).

wiegmanni_(m)_at_Sinharaja_1a(MMR)(05_17)_C-1700_1631875172.jpg)

The Sri Lankan kangaroo lizard Otocryptis weigmanni is frequently encountered in the forest.

The boundary of Sinharaja had originally been cleared and the Forest Department had planted fast growing Pinus caribaea (originally from Central America) to make a clear demarcation. The species is used in other areas in the Rakwana Hills for timber plantation purposes. In recent years, as ecologists realised the problems of reduced biodiversity and water retention in non-native plantations, efforts have been made to restore these zones with native plantations. Some natural succession was slowly taking place in these plantations but it was slow. A study by Nimal and Savitri Gunatilleke (Peradeniya) and Mark Ashton (Yale) showed that with careful thinning of the plantation and then the planting of site-appropriate species, processes of ecological succession could be accelerated. Today, most of this pine forest near the Kudawa entrance is on its last legs and a secondary forest, dominated by native species is on its way to taking over.

(05_18)_C-1700_1631875313.jpg)

The Sri Lanka green pit viper Trimeresurus trigonocephalus is an endemic found mostly in the wet and intermediate zones of Sri Lanka. Its close cousins – the large-scaled T. macrolepis and Malabar T. malabaricush pit vipers are found in the Western Ghats of India.

_C-1700_1631875425.jpg)

The extremely rare golden palm civet cat Paradoxurus zeylonensis photographed looking for food near a lodge on the boundary of Sinharaja.

SERENDIB SCOPS SENDOFF

On my last sojourn in Sinharaja, I was wrapping up a four-day field study with my students when we had an encounter with a shy and rarely seen species that is representative of endemism, scientific discovery and forest recovery in Sinharaja. My students had been investigating the impact of tourism on surrounding villages using face-to-face surveys in the home gardens of the Kudawa area. Daily routines had included going house-to-house, running the surveys. We were accompanied by some of the talented guides that normally work inside the park boundaries. Just as we were about to leave for Colombo, Wasala, our guide Thandula’s brother, came up breathlessly and said that he had seen a Serendib Scops Owl Otus thilohoffmanni roosting. He wanted to share it with us and my group was elated! A few of the students and my colleague Desline joined me as we took a short, strenuous hike that brought us face-to-face with this enigmatic species. It was only 20 years ago that Deepal Warakagoda discovered its mysterious existence and brought the Serendib Scops Owl to the world’s attention. Lying in a tangle of bamboo and pine needles we discretely gazed at it, took a few pictures and withdrew.

(05_17)_C-1700_1631875611.jpg)

Sinharaja’s rainforest canopy under the Milky Way – an unusual sight given that high humidity often prevents a clear view of the sky.

Leaving Sinharaja, I marveled at how one of the most difficult to see endemic bird species had found a home in a former plantation of Mexican pine trees outside of the original Sinharaja border. The sighting seemed to confirm the cautious lessons and optimism of Sinharaja, a once ravaged tropical rainforest that has been brought back from the brink.

WHAT WE CAN LEARN FROM SINHARAJA

l Citizen-based movements that push for protecting areas of ecological value are some of the most important initiators of authentic conservation success.

l Long-term scientific studies are vital to better understand the full value of tropical rainforest systems; there is still a great deal that we don’t know.

l Low-impact ecotourism can provide livelihoods for families living in the buffer zone of a Protected Area through employment as guides (both under the Forest Department or as private guides) and providers of services, including homestays.

l Ecotourism on foot, rather than jeep, offers a low-impact way to experience biodiversity beyond large charismatic species.

l Former tropical rainforest ecosystems that have been cleared and badly damaged by anthropogenic causes are resilient and have the ability to recover largely on their own, though active restoration efforts can accelerate the process.

WESTERN GHATS SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT DIFFERENCES

A defining aspect of the Conservation International-designated Western Ghats Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot is the idea of heterodox. This applies to the landscapes and abiotic aspects that determine what life forms and biomes/ecosystems each of its disparate zones support. The hotspot, in fact, stretches 1,800 km. from the basaltic Sahyadris, down through Goa and western Karnataka to the granite horsts of the southern Western Ghats. Sri Lanka and its dry, intermediate and wet zones is included in its entirety. The south western belt of Sri Lanka, where Sinharaja is located, is distinguished by its high rainfall. It’s not just that the wet zone has high rainfall but that it is a wet biome throughout the whole year. Some of the wettest areas in the Western Ghats may have equal or higher rainfall (think of Agumbe) but it is seasonal and falls for a few months, while being relatively dry for the remaining months of the year. Rohan Pethiyagoda and other researchers have drawn attention to this feature as a defining aspect that has given rise to the high levels of endemism in plants and animals in Sri Lanka’s wet zone. There are other factors of course, but Sinharaja straddles a key, relatively undisturbed area of this biodiverse wet zone.

(B_W)(01_17)_C-1920.jpg)

(B_W)(01_17)_C-1700_1631873105.jpg)

(12_18)_C-1700_1631873222.jpg)

_C-1700_1631873473.jpg)

-Sinharaja-Index-Map-(2019_04)_C-1700_1631873685.jpg)

(09_19)_C-1700_1631874498.jpg)

(05_18)_C-1700_1631874637.jpg)

(02_18)_C-1700_1631874740.jpg)

wiegmanni_(m)_at_Sinharaja_1a(MMR)(05_17)_C-1700_1631875172.jpg)

(05_18)_C-1700_1631875313.jpg)

_C-1700_1631875425.jpg)

(05_17)_C-1700_1631875611.jpg)