Seeding Conservation through Community Action

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 6,

June 2021

By Ajay Bijoor

The sun was up but I could barely stop shivering. Winter winds that cut through the valley can be felt in your bones irrespective of your layers of clothes. We were in Tsaba, one of several small valleys in the region of Gya-Miru in Ladakh at 4,200 masl. We had walked some hours to reach a rickety hut deep inside the valley. “Time for butter tea,” announced Karma Sonam, as he led us in. Karma le, our Field Manager, who lives in Rumtse village soon ushered us to a fire around which we huddled. Tashi Phuntsog, our host and local herder, answered our barrage of questions as he prepared our tea. Much of the conversation was in Ladakhi, but when he got around to Hindi he said that we were a touch late this year. The argali had already moved higher up. We would need to head to Kyamar to sight them.

While the prospect sounded exciting, it would involve more walking! We camped at Kyamar and when we left to survey our surrounds the following morning, it took little time for us to get our first look at a herd of Tibetan argali. The rams of this species of mountain sheep are a sight to behold, especially in their fine winter coat. We were there towards the end of their rut and noticed hectic activity in the herd, which we scanned through our binoculars. Amazingly, Tashi Phuntsog knew their movement and habits. We felt good to know that there were more like him in these valleys who cared for the majestic animals even though their own domestic herds grazed in the same pastures.

Ladakh – One of a kind

Geographically, Ladakh is a trans-Himalayan cold desert located between the Karakoram range to the north-west, the Zanskar range to the south-west, with the Ladakh range running along the north bank of the Indus river, which enters at Demchok at Ladakh’s southeastern tip.

Its unique geographical location makes it the distribution limit for several species found across the wider mountain habitats of the Hindu Kush, Himalaya, in Central Asia. This includes carnivores including the snow leopard, Tibetan wolf, Eurasian lynx, brown bear and Pallas’s cat, and ungulates such as bharal, Himalayan ibex, Tibetan argali, Tibetan gazelle, Tibetan antelope, Ladakh urial and kiang. Additionally, the landscape is home to over 300 species of birds, including the charismatic Black-necked Crane. Not surprisingly, the region has always interested ecologists. Our own efforts began with staff training and joint surveys carried out with the Department of Wildlife Protection.

Initial field surveys in Changthang and Nubra regions in the early 2000s were followed by species-specific surveys for Tibetan gazelle (2001-03), Ladakh urial (2003-04), kiang (2001-06) and Tibetan argali (2005-09). Much of this work was initiated and led by Yash Veer Bhatnagar first as a scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and later with the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF). Such surveys also provided opportunities for Ladakhi youth and young researchers to participate in systematic field studies. These surveys, along with concurrent work from other snow leopard landscapes in Himachal Pradesh and the newly formed Uttarakhand, laid the foundation for Project Snow Leopard (see more in box below).

Snow leopard landscapes in India share typical characteristics. They constitute a continuum of habitats from Kashmir in the west, to Arunachal Pradesh in the east. The fact that they are sparsely populated (two to five people per square kilometre) probably enables both people and wildlife to co-exist at low densities. These regions are traditionally inhabited by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities dependent on high-altitude pastures that also support much of the wildlife. Clearly any attempts to conserve wildlife must involve the active participation of local communities and this means looking beyond the conventional approach of Protected Area management. Such insights were built into Project Snow Leopard, which advocates a participatory approach to the conservation of rare high-altitude wildlife… even as it adopts a landscape-level strategy to manage this fragile ecosystem. Towards this end, the first national workshop for Project Snow Leopard, convened in Leh in 2006, was officially launched by the Ministry of Environment and Forests in 2009.

Photo: Udayan Rao Pawar

Project Snow Leopard and Union Territory-Wide Snow Leopard Monitoring

Photo: Udayan Rao Pawar

Project Snow Leopard and Union Territory-Wide Snow Leopard Monitoring

The MoEFCC initiated Project Snow Leopard (PSL) in 2009 to enable scientific, participatory and landscape-level conservation of the high-altitude areas of the Himalaya, a programme catalysed by NCF and other partners. However, with little credible information on snow leopards in Jammu and Kashmir, the programme primarily remained focused in Ladakh. With the designation of the new union territory, J&K Department of Wildlife Protection (JKDWP) is now keen to benefit from this national programme for the conservation of the high-altitude areas that cover over 12,000 sq. km. NCF will support the Wildlife Department to identify the best candidate for their PSL landscape and, with other local institutions, also assist in preparing its management plan with the PSL management planning guidelines.

Understanding the population status of any species, especially a flagship such as the snow leopard, is crucial to plan and monitor conservation programmes in any area. The inhospitable habitat of this elusive cat made it even more difficult to estimate its numbers. Till about a decade ago, a reliable estimate of its population was not available for even Protected Areas, but advances in camera trapping, molecular methods and statistical analyses, have changed this. Using the best knowledge developed in studies across many countries, the Global Snow Leopard Ecosystem Programme, a joint initiative of the 12 range countries and conservation partners, put together a protocol – the Populations Assessment of World’s Snow Leopards (PAWS) in 2019. NCF facilitated the adaptation of this protocol by the MoEFCC, in partnership with other scientific organisations and the state forest departments in what was called the ‘Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India’ or SPAI. This protocol has a two-step sampling approach to cover a bulk of the snow leopard’s range in each of the six states and union territories in the country. The first step is estimating the occupancy of snow leopard and prey species across the state, stratifying the region as per habitat quality, and then estimating abundance of species in a reasonable area within each strata using camera trapping based analyses. This is a massive exercise, and the Himachal Pradesh Forest Department has recently completed it for their state in collaboration with NCF. We are now assisting JKDWP to design and implement SPAI. Since many areas within J&K have restrictions, we plan to have concerted fieldwork by well-trained forest staff and volunteers so that the occupancy and abundance surveys can be completed in one go. For abundance, together with national and state-level institutions, we plan to rely on genetic tools that can be more effective in this situation.

Making conservation participatory

Field surveys carried out through the 2000s helped identify areas of high wildlife value in parts of Ladakh. Among these was Kalak Tartar near the remote settlement of Hanle in Changthang. This rolling plateau was home to a small population (c. 50) of Tibetan gazelle (the largest in Ladakh) with another smaller population reported from Sikkim. Proximity to international borders added to the risk faced by the species, as it witnessed a precipitous fall in numbers at the hands of hunters across the border.

The Changpa herders of the region, however, maintained an uneasy truce with the species that compete for sparse forage with their livestock. In 2007, a dialogue with the herders led to the setting up of a socially-fenced reserve – a small area to be kept free from livestock grazing in exchange of monetary support – in the hope that this might provide forage and refuge to the gazelle when it was most needed in the harsh winter months. What is more, the herders agreed to keep watch on the endangered gazelle and report their presence at regular intervals. This idea was built on our successful work in neighbouring Spiti, where work led by Charudutt Mishra had succeeded in augmenting ungulate populations. Soon after, a similar arrangement was worked out in the Gya-Miru region, which was home to a population of Tibetan argali. Here it was herders such as Tashi Phuntsog that served as the argali’s guardians.

For the herders themselves, such efforts were not a significant departure from their traditions. Petroglyphs found across Ladakh that date back c. 5,000 years generously depict scenes involving herders, livestock and wild animals. Local folklore is rich with references of wildlife, even describing them as having humanlike attributes of intelligence, fairness and guile. However, the possibility of negative interactions with wildlife always persists. Livestock depredation by carnivores is a reality that herding communities live with across the snow leopard range. Incidents of ‘surplus killing’ of livestock by carnivores though rare do take place. Such incidents can wipe out a large part of a herder’s stock in a single event. When such unfortunate incidents occur, the risk of retaliatory killing, or at least, highly negative attitudes, are inevitable.

Petroglyphs, carved c. 5,000 years ago in Ladakh, depict scenes of humans, wildlife and livestock. Photo: Prasenjeet Yadav.

Ungulates, on the other hand, are often seen as direct competition for livestock forage, as exemplified by herder perceptions of the kiang. Interestingly, our studies revealed that the conflict was primarily for the scarce moist sedge meadows near lakes and valley bottoms where kiang congregated in autumn for their annual rut, when the forage they consume is badly needed by herders as winter-reserve pasture.

The herder’s life is challenging from braving harsh weather to protecting their herds against unforeseen risks. Expecting them to also support conservation is unreasonable, unless these measures also secure their livelihoods. Most of our wildlife conservation efforts over the past decade has been concentrated on creating conditions that enhance their incomes, thus allowing traditional pastoral communities to participate and benefit from conservation.

In Eastern Ladakh, home to pastoral communities including the famous Changpa, our initial attempts sought to minimise the risk of conflict and to set up mechanisms for financial relief if and when conflicts took place. This led to the first community-based livestock security programme in 2005, whereby herders contributed a mutually agreed amount to insure their livestock. The planning and running of the programme were undertaken by the herders themselves, who received matching contributions to their collections to make the programme partially sustainable. Such programmes allowed herders to avail financial relief when livestock losses occurred and since the programme was fully administered by locals – and involved a financial cost for participation – there was a lower risk of false claims and attempts to ‘game the system’. Other efforts that started in 2011 involved predator-proofing night time corrals to prevent carnivores from entering them, thus preventing incidents of surplus killing. Under such arrangements, herders with vulnerable corrals received support to refurbish them.

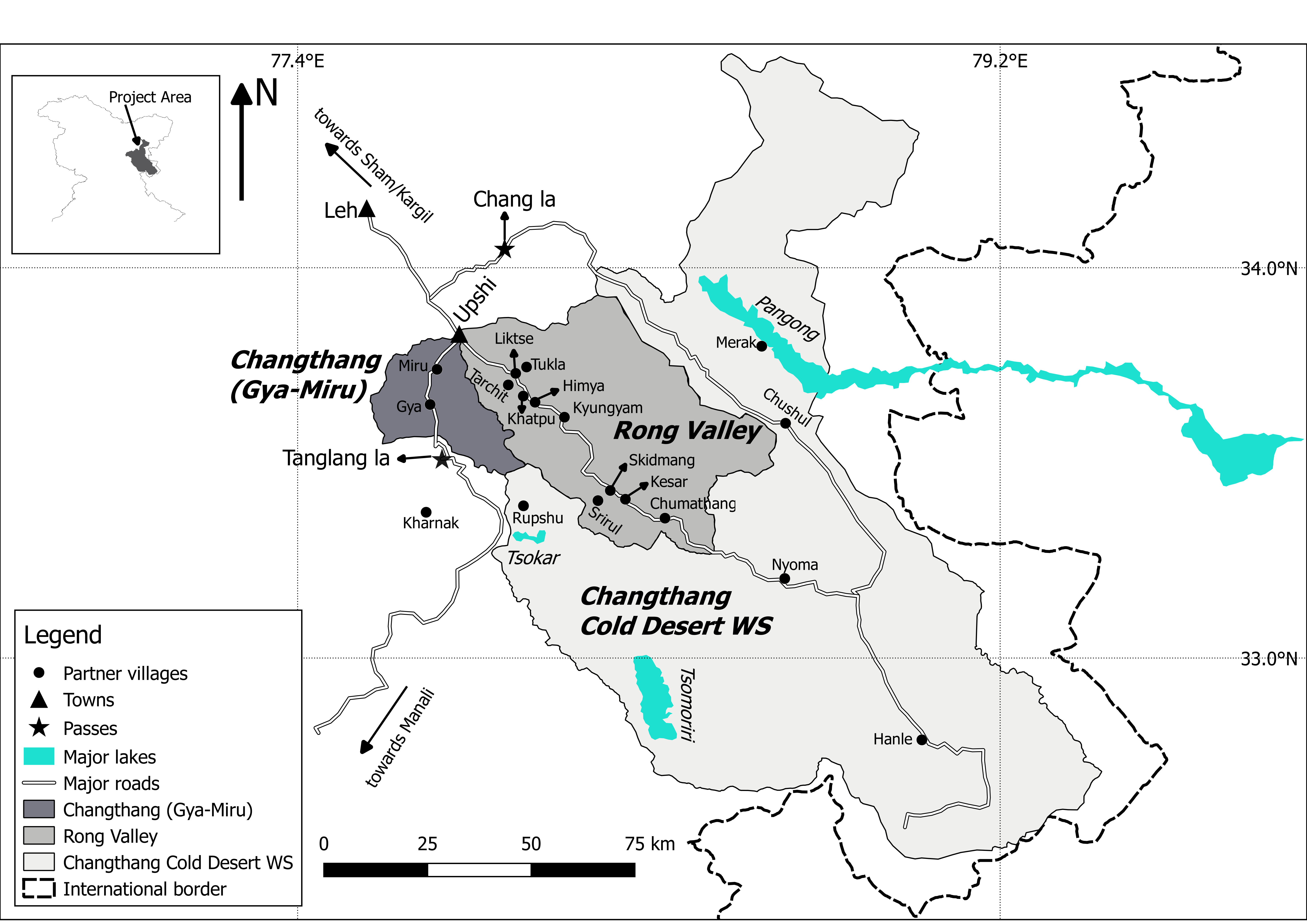

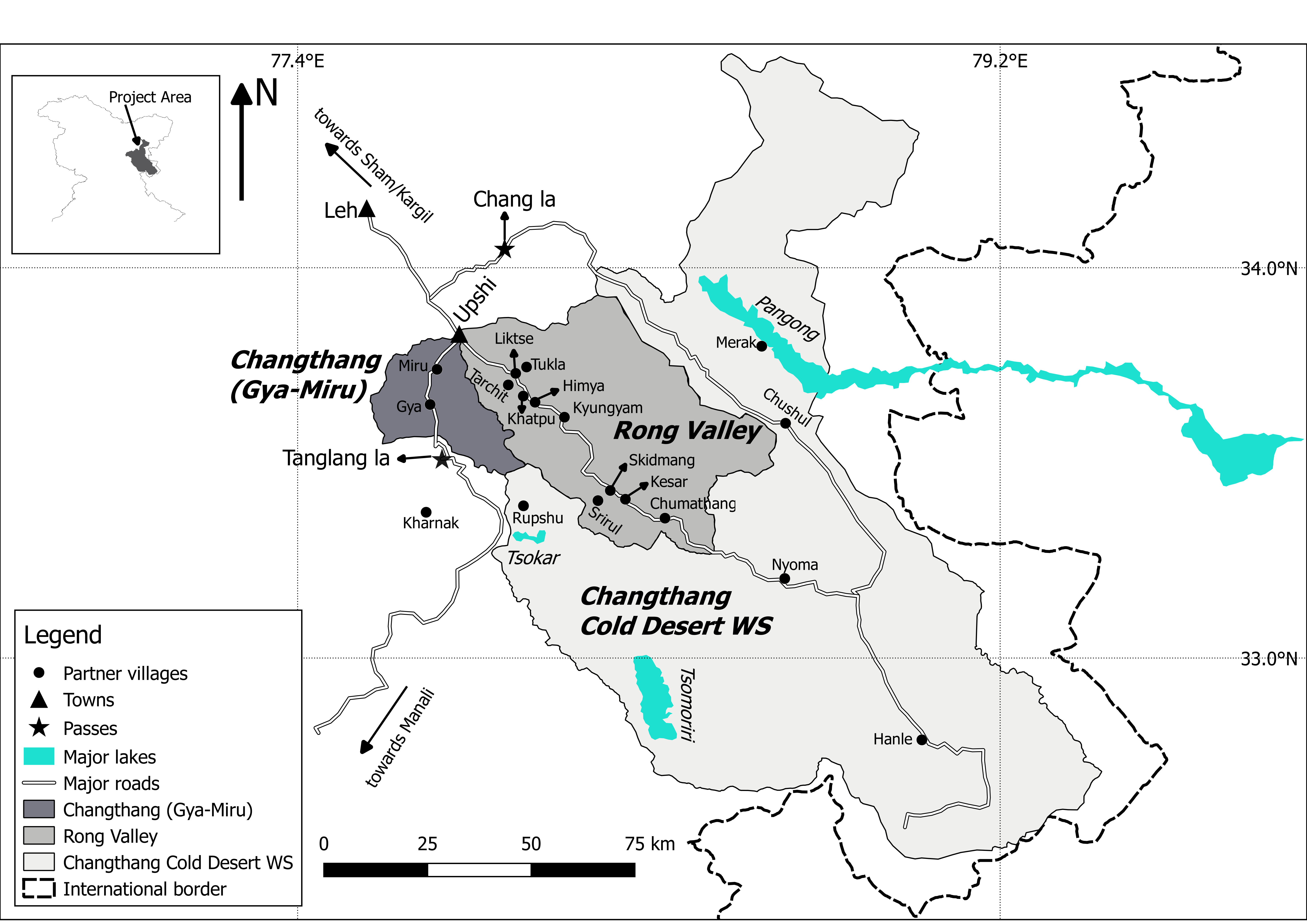

A map of the trans-Himalayan cold desert that is Ladakh, highlighting the Nature Conservation Foundation’s project survey areas to assess species density. Map Courtesy: NCF.

Soon more herding communities agreed to set up grazing-free reserves within their pastures and this helped revive pastures and ungulate populations. Our role was restricted to seeding the idea and offering technical and financial support when conservation interventions were required. The process was entirely managed by the community, which helped because each community faces unique challenges and the interventions became locally relevant and fair to all.

All this was made possible on the ground, thanks to a small but strong local team we were able to build over the years. Led by individuals like Karma Sonam, our frontline team became the first point of contact for herders with whom we initiated all of our efforts. Pari passu, the team led field surveys with various researchers who have supported our work down the years.

NCF focusses on building alliances for conservation, and partners with the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council to boost the pashmina wool sector, to benefit herding communities. Photo: Sonam Tsering.

Adapting to Change

Over the past decade, Ladakh has witnessed enormous change. Tourism has grown exponentially, and communities in even the remotest corners seek to benefit from the influx. This led us to partner with local Ladakhi organisations like the Snow Leopard Conservancy - India Trust, to expand their popular Himalayan homestays into Eastern Ladakh. Local homestay owners were provided support and training to sensitively host travellers. This period also saw a rise in urban migration to Leh, especially among the younger Ladakhis in search of better education and livelihood prospects.

An environmental education programme started in 2010 targeting local school students of Leh and government schools of Eastern Ladakh helped us introduce education activities to reinforce the connection of children with nature and the outdoors. The nature education camp saw children camping outdoors, which almost always left them with a greater and lasting appreciation for their own local flora and fauna. The emphasis was on inculcating appreciation and values using all their senses… not entirely on knowledge.

In 2010, NCF began conducting interactive outdoor nature education camps for young students in Leh and Eastern Ladakh, focused on creating knowledge and an appreciation for flora and fauna. Photo courtesy: NCF HAP.

Throughout the years, we have worked with local communities to set up interventions that address a range of conservation threats. Such partnerships provided opportunities for local ingenuity to surface. For example, the prevalence of traditional wolf traps, or shangdong, across Ladakh was a key conservation challenge. These structures were once used by herders to trap and kill wolves to protect against livestock losses. Such traps are rarely used now, because local communities have become the beneficiaries of biodiversity, including wolves and other species. Consultations with local herders led to the idea of building a stupa (an auspicious Buddhist structure) alongside the shangdong to reaffirm their commitment to respectfully coexist with wildlife and cause no further harm. This led to the Shangdong to Stupa initiative in 2018 that saw herders from Chushul neutralising their traditional wolf traps without destroying the structure. The stupa thus built was consecrated by local religious heads who backed this idea and encouraged more communities to adopt such proactive conservation measures.

A traditional shangdong, built to trap wolves. Local communities whose livelihoods are affected by livestock depredation often set up traps to capture wild predators. Here is a neutralised shangdong and stupa at Tsaba valley. Photo: Rigzen Dorjay.

As a wildlife research and conservation organisation, field research laid the basis for identifying threats and initiating conservation efforts. What followed was an attempt to build a long-term engagement with pastoral communities, who have remained our strongest allies. Despite the challenges faced by them, these communities persist in sharing space with rare, high-altitude wildlife. More recently, our efforts have been to try and synergise alliances for conservation that can have a scalable impact. Working with the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council we are working to boost Ladakh’s pashmina wool sector to provide livelihood benefits for Changpa herders and Tibetan Refugees (TRs) engaged in herding across the Changthang region of Ladakh.

A look back at the past two decades reiterates the fact that conservation threats evolve over time. Even a region as remote as Eastern Ladakh has seen dramatic change in this period. Even as you read, several parts of Eastern Ladakh are facing a new challenge from the increasing tensions at the Indo-Chinese border. While these have severe geo-political impacts, they also affect the daily lives of the herders, their livestock and the wildlife that co-inhabit this space. One clear impact is the loss of precious pastures due to such disputes. The safest bet to preserve these unique ecosystems is to back local communities by empowering them to address their own conservation concerns.

Acknowledgements: Our work has hugely benefitted from the continuous support and guidance of various officers in the Department of Wildlife Protection. We also acknowledge the support of officers in the Sheep Husbandry Department and elected representatives of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council. Our work was also made possible by the generous support of the NatWest India Foundation (previously RBS Foundation India), and the Snow Leopard Trust.

Species Surveys In J&K

Kashmir valley is nestled between Zanskar range in the north and Pir Panjal in the south. North of the Zanskar range is the Gurez valley formed by the Kishenganga river and south of the Pir Panjal, the mountains taper down to the subtropical Shiwalik hills of Jammu. This diverse region harbours the hangul, musk deer, Himalayan tahr, goral, brown and black bear, snow leopard, common leopard and other species. While there was some information on the state animal, hangul, even basic information on the occurrence of the other species was mostly lacking.

There was almost no information available on the markhor either. In the mid 2000s, with the Wildlife Trust of India and the J&K Department of Wildlife Protection (JKDWP), NCF scientists initiated a survey of the potential range of the markhor. This survey was conducted in partnership with the Indian Army and confirmed a reduction of 60 per cent in its range since India’s independence and barely 300 animals surviving in the state, most of these in the Kazinag Mountains in the Uri sector, on the Line of Control with Pakistan. Other populations seem to have perished to hunting and developmental pressures; a small population that survived in the Hirpora Wildlife Sanctuary is under threat from the blacktopping of the Mughal Road (first carved out by emperor Akbar’s invading army) set up to connect Rajouri to Srinagar. Aided by this study, the JKDWP designated a 160 sq. km. area as the Kazinag National Park in 2007 to strengthen markhor conservation. We soon followed this with another collaborative project on markhor ecology led by a researcher from WTI, Riyaz Ahmad. It studied the seasonal habitat use and diets of markhor and highlighted the tremendous threat being posed by the increasing livestock of the transhumant herders that visit the area during the short summer season.

In partnership with the State Forest Research Institute, we conducted pioneering surveys in little-known areas in Gurez and Jammu, and Bani-Sarthal region in Kathura District, adjoining Chamba in Himachal Pradesh. In Sarthal, we focused on confirming the occurrence of the Himalayan tahr. The Sarthal area is a stunning alpine meadow leading over the Chattar Pass into the Chenab Valley and was recommended as a site suitable for developing responsible tourism. In Gurez, we documented the presence of snow leopard, ibex and musk deer with the possibility of hangul venturing in some of the upper valleys along the southern banks.

A young researcher from Kashmir, Munib Khanyari, is now planning more detailed work in Gurez and other areas of Kashmir that should lead to more interesting conservation initiatives in the region.

Ajay Bijoor works with local communities and government agencies to plan and implement conservation action in parts of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh. He also supports research activities. He is Assistant Programme Head of the High Altitude Programme in NCF and hails from Mumbai.