Securing the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 4,

April 2021

The Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) recently concluded a year-long occupancy survey for four large carnivores in the vital Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. Wildlife biologist Girish Punjabi, who is in charge of the project, speaks to WCT’s Conservation Writer Rizwan Mithawala about valuable insights from the survey, and WCT’s multi-pronged approach to help protect this corridor.

You have devoted around a decade, as a biologist, studying and trying to protect the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. Where is this corridor and why does it matter?

The Sahyadri-Konkan corridor, part of the north-central Western Ghats, is a linear montane habitat that connects the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve (STR) in Maharashtra to the Kali Tiger Reserve (KTR) in Karnataka. The Western Ghats is a crucial habitat for wildlife and biodiversity, and the Sahyadri-Konkan region is the northern range-limit for three of the four large carnivores found in the Western Ghats – the tiger, dhole and sloth bear. This is why this region matters, as chances of local extinction of these species are very high here. Tigers need targeted protection efforts for population recovery, and KTR and adjoining Protected Areas in Goa-Karnataka harbour the main source population for STR. The only way a dispersing tiger can colonise STR is through the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. In some parts, this corridor is narrower than one kilometre; therefore, saving these bottlenecks is crucial. Tillari, for example, is a critical bottleneck, which connects Maharashtra’s Western Ghats with that of Goa and Karnataka. The sloth bear and dhole fare relatively better in the region but are still threatened due to fragmentation. Neither of the species find it easy to traverse through large tracts of human-dominated habitat. Therefore, the forested corridor is crucial for both of these species as well.

Your study area is not a contiguous stretch of undisturbed forest. It is interspersed with agriculture, plantations and human settlements. What determines the occurrence of large carnivores here? What makes it work or not work for them?

The Sahyadri-Konkan corridor has high human density, and a lot of land is under private ownership. The forest on much of these private lands is long gone, and what remains is degraded or being transformed into cash crop plantations. In such fragmented landscapes, the occurrence of large carnivores must be examined at the landscape scale, and the responses of large predators to human pressures are species-specific. For example, from our studies, we have found that the tiger is largely found in forested regions closer to its source population (i.e. Kali Tiger Reserve). Therefore, the remnant habitat in the corridor is crucial for tiger movement and colonisation from the source. For the dhole and sloth bear, Protected Areas are important for their persistence in this landscape, and livestock presence negatively affects their occurrence. The leopard, on the other hand, occurs almost everywhere, including regions with high livestock densities.

WCT has recently completed an occupancy and distribution survey of large carnivores in this region. Since you first started research here in 2010, what has changed?

A lot has changed and interestingly, for the better! In a nutshell, after nearly 10 years, through our study that was ably supported by Vinati Organics Limited, we found that at a landscape-scale, large carnivore occupancy has either increased (for tiger and dhole) or remains more or less the same (for sloth bear and leopard). While ecological data is very noisy (i.e. the patterns are not very clear), for species that are low-density, our study still confirms that improvement in landscape management after the declaration of the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve in 2010 has definitely helped in the sustenance of large carnivores. What’s necessary now is to protect the corridor and improve the state of existing Protected Areas, such as the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and the newly-notified Tillari Conservation Reserve.

A view of the Radhanagari landscape with the backwaters of the Kalammawadi dam on the Dudhganga river. Radhanagari is a potential site for tiger recovery in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape. Photo: Anish Andheria.

Can you elaborate on how the declaration of the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve has helped large carnivores in this region?

The declaration of the tiger reserve in 2010 brought in more protection and funds from various quarters, including the State Forest Department, the National Tiger Conservation Authority and several NGOs. Also, the wider debate about declaring Ecologically-Sensitive Zones/Areas in the Western Ghats, after the centrally-commissioned Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel and High Level Working Group reports were published, gave the region much-needed attention. Protection efforts have also improved the quality of wildlife habitat in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve. Battles have been fought by activists over illegal mining, windmills and hydro-projects. Also, most importantly, several forested patches along the corridor are now being formally notified as Conservation Reserves. This makes it one of the few landscapes in the country where the corridor will almost entirely become a network of Protected Areas.

Tillari was finally declared a Conservation Reserve in June 2020. It’s quite small; how would it help tigers and other wildlife?

The Tillari Conservation Reserve (TCR) is approximately 30 sq.km. of protected land at the Maharashtra-Goa-Karnataka tri-junction. The reason that this small region is critical is that it is a pinch-point for tigers and other large wildlife movement from the source population in Karnataka into Maharashtra. More areas can be added to TCR, but that would require acquiring large parcels of private land. These lands are forested right now, with small holdings of cashew and some large rubber estates. Protecting the surrounding forest patches is of utmost importance for Tillari to serve the role of a long-term stepping stone tiger habitat for STR.

The endangered dhole, or Asiatic wild dog, has benefitted from protection of large parts of the Sahyadri-Konkan region. WCT’s survey reveals that the dhole occupies nearly 80 per cent of the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria.

The endangered dhole, or Asiatic wild dog, has benefitted from protection of large parts of the Sahyadri-Konkan region. WCT’s survey reveals that the dhole occupies nearly 80 per cent of the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria.

What factors determine whether tigers will colonise a forest patch?

Tigers are sensitive to human disturbance. We find evidence of tigers only in the most undisturbed habitats. From our 10 years of study, I have found that tigers occur largely where forest cover is high and in areas close to the source population in Karnataka, that is, the areas south of the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary seem to have the most individuals. This is not to say that there aren’t reports from STR further north, but these are usually male tigers that disperse large distances. There are no confirmed records of any tigress in STR until now. Protection of the forests in the corridor therefore seems the most crucial next step for natural colonisation to occur.

Is it possible to make these tiger populations viable? What would it take?

In the distant future, yes! But for now, protecting these few remaining individuals is the key. Currently, breeding tigresses are present only in the Tillari and Chandgad region, south of the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, based on all the evidence collected. Unless the corridor to the north of this area is strengthened, breeding females will find it difficult to stabilise in the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and STR. It would take long-term commitment and strategic action for protection levels to improve in the entire landscape, especially the corridor. Presently, political will seems to favour this.

What about dholes? How have they been faring and how are their needs different from tigers?

Dholes are faring relatively better than tigers in terms of area of occurrence in the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. They occupy close to 80 per cent of the landscape as compared to tigers, which occupy about 60. But dholes also suffer from the effects of fragmentation and prey depletion and we still understand little about their population dynamics. Dholes live in packs and only the alpha male and female are known to breed, so the breeding population is considerably lower than the total number of individuals. Also, since dholes live in a pack and feed on the kill together, sometimes the entire pack can get wiped out due to retaliatory poisoning or disease transmitted by domestic dogs. Although poisoning is rare in the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor, more common is the stealing of the kill by local people when they encounter a freshly hunted sambar in the forest. This can be resolved through awareness of the law and better protection measures.

Tiger pugmarks on river sand in one of the last remaining tiger habitats in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape. Photo: Amit Sutar.

And sloth bears?

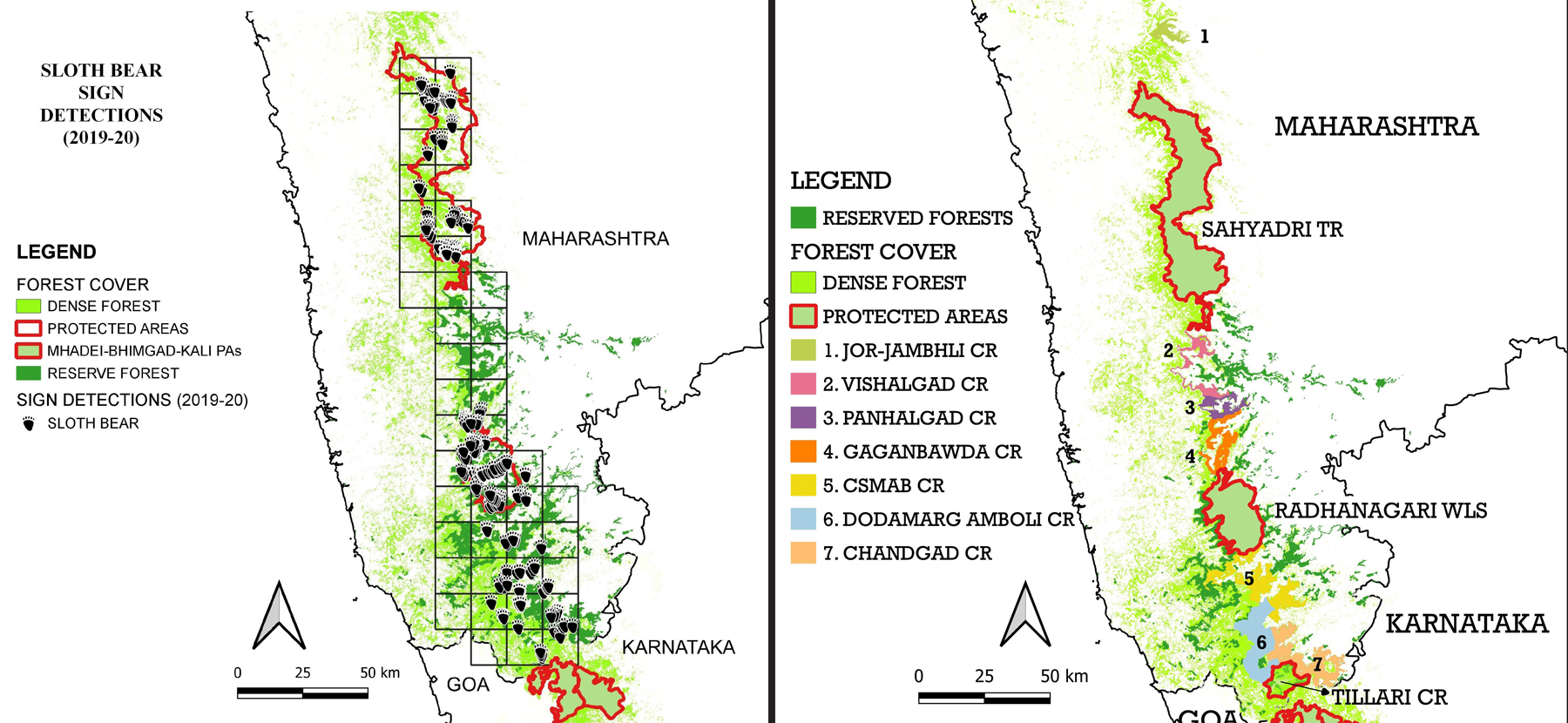

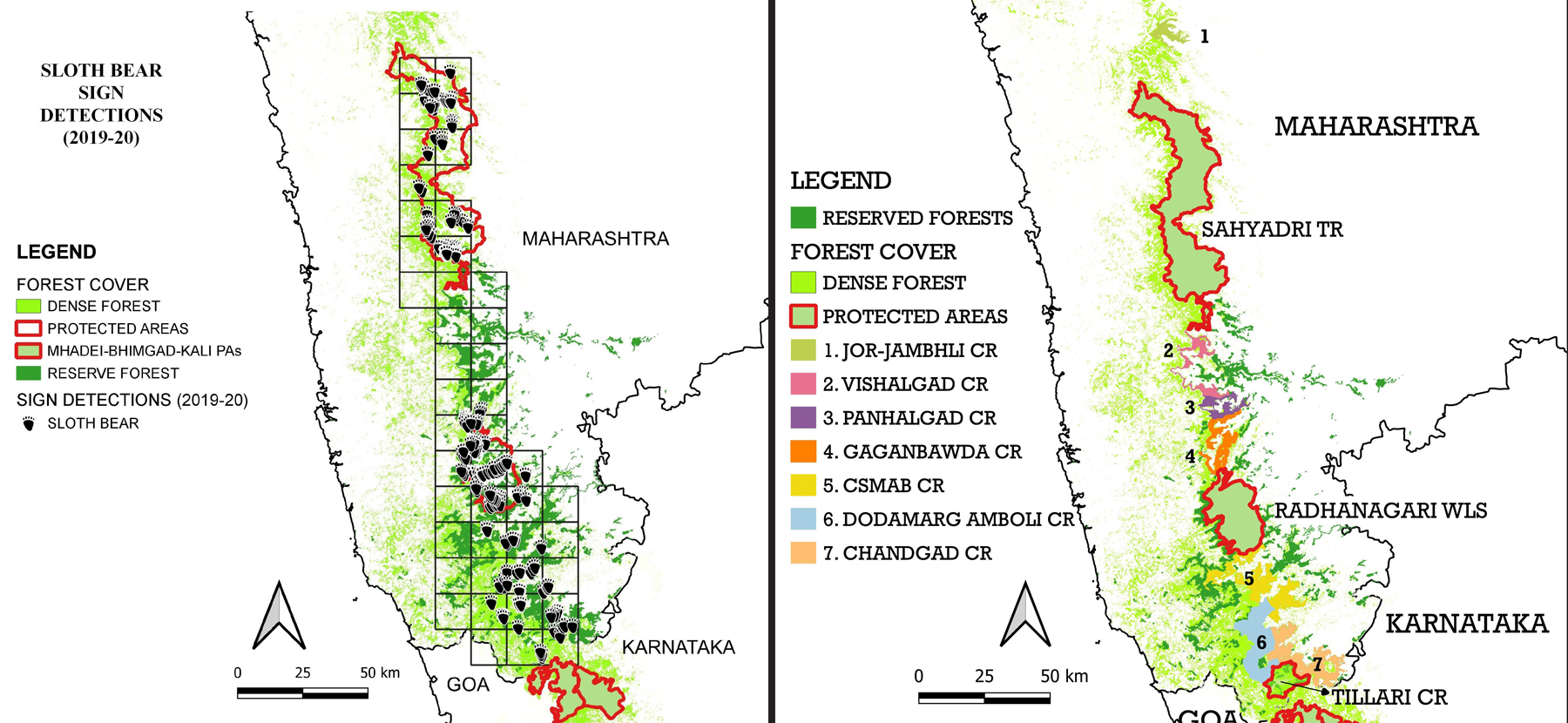

Sloth bears occur in two sub-populations in the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor – one in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and the other in the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and further south in the corridor. There are no sloth bears in the corridor between STR and Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, which is almost 50 km. in length (straight-line distance). We found these patterns to be consistent in our two landscape surveys over the last decade. This means that the STR sub-population is cut-off from the population further south. This will eventually have genetic consequences for the former and will likely need management interventions if bears fail to naturally colonise the corridor habitats between the two Protected Areas.

How are leopards different?

Leopards are doing significantly better than other predators in the northern-central Western Ghats, as would be expected of these highly adaptable carnivores. They occur in 96 per cent of the landscape and even in areas that have high livestock densities, demonstrating their ability to survive in human-dominated landscapes. Interestingly, the encounter rate of preferred wild prey (small and mid-sized species) and forest cover were found to be positive influences on leopard occupancy, indicating that wild prey and habitat are also important for leopards.

Since 2010, wildlife biologist Girish Punjabi has spent much of his waking hours trudging the Sahyadris, studying and working to protect this fragile ecosystem. Photo: Raman Kulkarni.

Since 2010, wildlife biologist Girish Punjabi has spent much of his waking hours trudging the Sahyadris, studying and working to protect this fragile ecosystem. Photo: Raman Kulkarni.

Do we need species-specific measures?

For large-bodied wildlife, yes. While the tiger is a suitable umbrella and flagship species, each predator has its own set of management requirements. This brings us to the importance of encouraging systematic long-term research studies, which are invaluable in guiding management action and shaping conservation outcomes.

Recently, seven new Conservation Reserves were proposed in this region. How will these improve connectivity?

After the declaration of the Tillari Conservation Reserve in June 2020, the State Forest Department proposed seven more Conservation Reserves in the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor, out of which five were notified in March 2021. This would protect an additional 870 sq. km. of forest habitat along the corridor and make this region one of the few in the country where the entire corridor is formally protected. Usually, corridors largely remain as Reserve Forests, under the control of the Territorial Wing of the Forest Department. Needless to say, such areas are easily threatened by large infrastructure projects.

The recent occupancy study by WCT can help build a roadmap for long-term conservation efforts and management action in and around the proposed CRs, and the entire Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. Where do we begin?

After their formal notification, efforts should be directed to improve the state of wildlife habitats in the new CRs. This can be done through trainings to build the capacity of frontline forest staff. We need to reorient the staff towards protection, as the Territorial wing of the Forest Department is generally not oriented towards wildlife protection. Wild prey densities will improve once livestock pressures on the forest reduce, but this would require innovative mechanisms to change the way local people look at forests. For now, the forest is a source of free fodder and firewood, but this needs to change. This can largely happen through awareness about better technologies for fuel, access to improved livestock breeds and husbandry, job security through eco-tourism, and other community-level interventions.

(Left) The sloth bear likely occurs in two sub-populations in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape: one sub-population in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and the other in the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and further south. No bear signs were detected in approximately 50 km. of the corridor between these two PAs in 2019-20. (Right) The newly proposed Conservation Reserves will protect almost 870 sq.km. of corridor habitat in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape, making it one of the few landscapes where the corridor is almost completely a network of PAs. Maps courtesy: WCT.

(Left) The sloth bear likely occurs in two sub-populations in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape: one sub-population in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and the other in the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and further south. No bear signs were detected in approximately 50 km. of the corridor between these two PAs in 2019-20. (Right) The newly proposed Conservation Reserves will protect almost 870 sq.km. of corridor habitat in the Sahyadri-Konkan landscape, making it one of the few landscapes where the corridor is almost completely a network of PAs. Maps courtesy: WCT.

How to secure, protect and manage the corridor in the long-term?

First and foremost, any major infrastructure through the corridor needs to be re-considered. We should avoid diverting any more forest land in the corridor for ‘development’, as what we have left now is the bare minimum. Existing infrastructure that is cutting the corridor should factor in strict mitigation measures at the time of upgradation, to facilitate animal movement. Secondly, scientifically and socially sound management plans should be drafted and followed, to provide protection and to manage the corridor habitats. Thirdly, local people need to become partners through innovative mechanisms that have tangible benefits for them. And lastly, frontline forest staff capacity and safety needs should be upgraded through training.

How can the support of local communities be secured and they be made a part of this?

We need to identify villages that suffer most due to human-wildlife conflict in the corridor. Conflict may be due to crop or livestock loss, or in extreme cases, loss of human life. This can have a serious impact on financially-weaker households. Once identified, these households should be engaged with to understand their grievances, aspirations, and suggestions. Government schemes should be brought to their doorsteps and a serious effort should be made to enhance their livelihood options. Social scientists should work closely with conservation biologists to study and suggest interventions that create win-win solutions for people and wildlife. Community-led or private eco-tourism ventures can create job opportunities for locals and improve local attitudes towards wildlife and forests.

A sloth bear dropping, containing the exoskeletons of ants and other insects, impregnated with large quantities of soil. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria.

A sloth bear dropping, containing the exoskeletons of ants and other insects, impregnated with large quantities of soil. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria.

What are WCT’s plans to secure these new PAs and the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor?

WCT plans to work with the Forest Department to build capacity and support conservation efforts in multiple ways. For now, our plans are to train frontline staff in law enforcement, forensics, trauma management and wildlife monitoring. At the same time, we will also support the Department in drafting Management Plans for the newly-approved Conservation Reserves and provide inputs for the Tiger Conservation Plan for STR. Targeted research projects may be taken up to understand specific issues such as human-wildlife conflict and measures to enhance livelihood opportunities for local people.