Rhythms Of Coexistence

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 6,

June 2025

By Mohd. Shahnawaz Khan

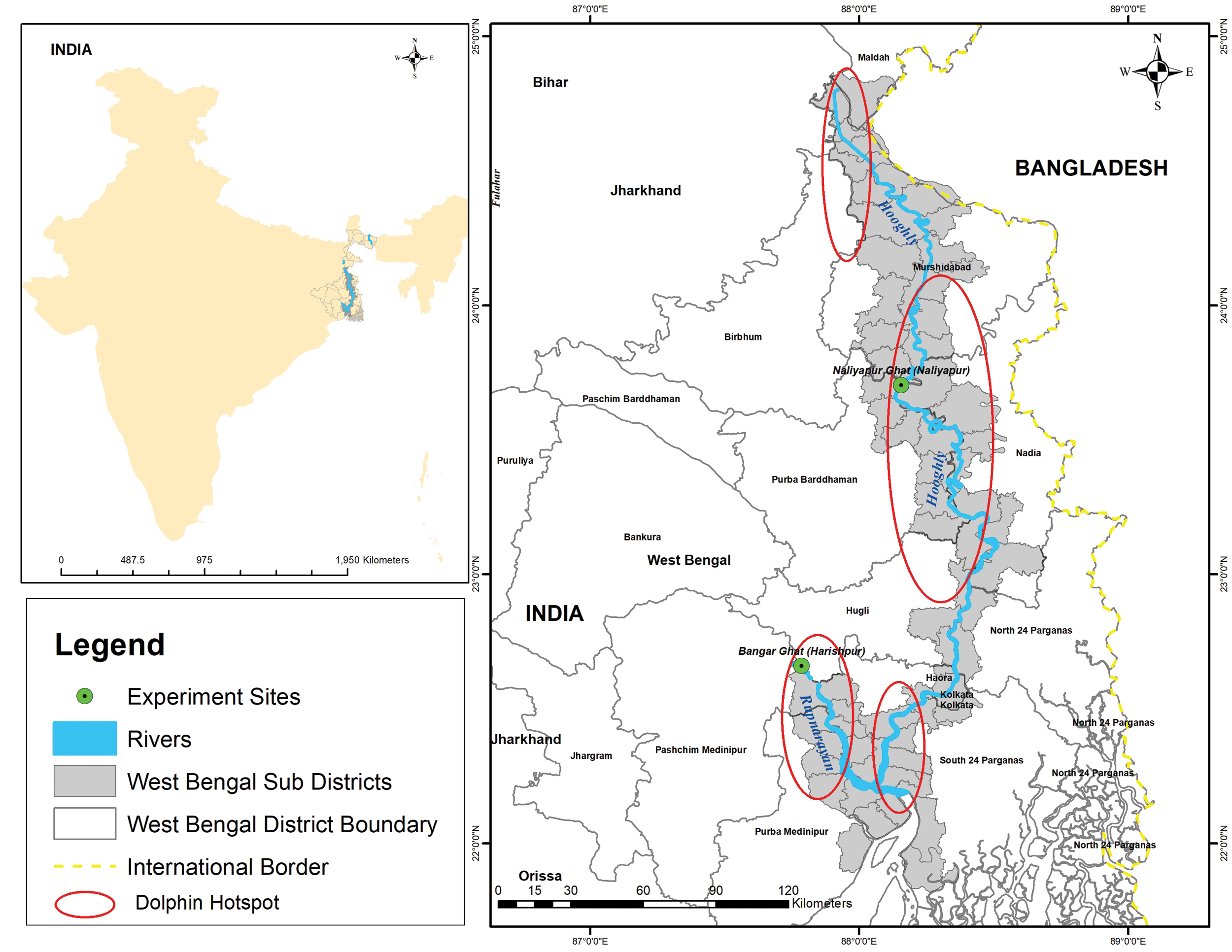

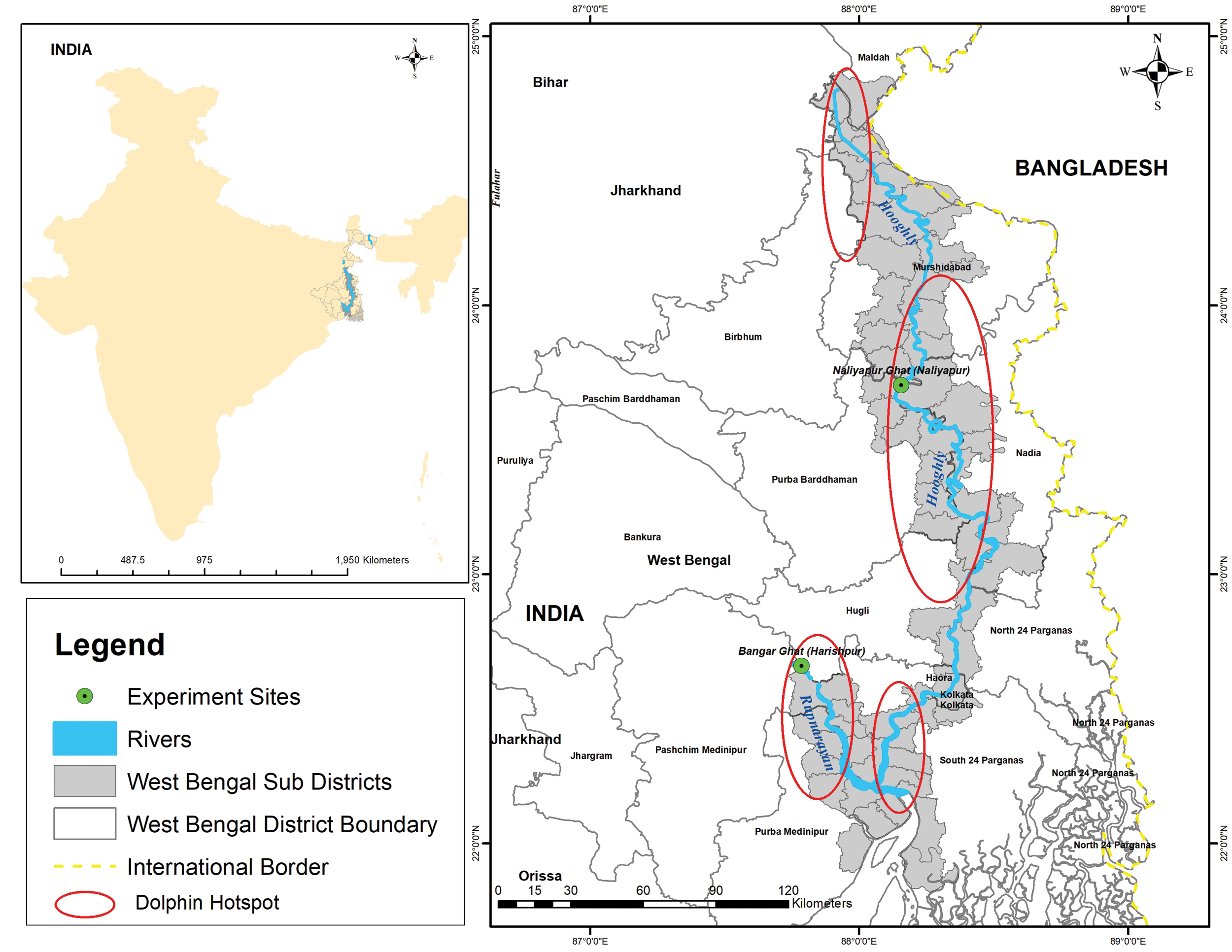

In the gentle flow of West Bengal’s Hugli (Hooghly) and Roopnarayan rivers, a quiet change is underway for Ganges river dolphins and local fishers.

I’ve always been drawn to rivers – their quiet power, their life-giving flow, and the secrets they carry beneath the surface. One of those secrets, known to only a few, is the Ganges river dolphin Platanista gangetica. This remarkable, nearly blind creature once thrived in great numbers across the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna system. But today, their world is shrinking. Their habitats are fragmented, and their numbers dwindling. Most troubling of all, fishing nets – especially gillnets – have become silent killers, claiming dolphins one by one.

But I’ve also seen hope glimmering below the surface.

Between 2022 and 2024, I had the chance to be part of something meaningful. Alongside colleagues from WWF-India, the West Bengal Forest Department, and the Wildlife Institute of India, we launched a long-term study to test a ‘pinger’. It is a small, unassuming device – just a cylinder that emits high-frequency sound pulses underwater. The idea is simple: alert the dolphins before they get too close to fishing nets.

In the stillness of the river, the Ganges river dolphin emerges – an ancient inhabitant of Indian rivers. This remarkable, nearly blind creature once thrived in great numbers across the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna system. Photo: Soumen Bakshi/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

If you know anything about Ganges river dolphins, you know they 'see' with sound. Their echolocation is extraordinary. But sadly, it doesn’t help them detect modern monofilament gillnets. The nets are invisible to their sonar, and entanglement often leads to drowning. For local fishers, these nets are a livelihood – cheap, effective, accessible and widely used. But they’ve also become a flashpoint between conservation and community needs. Additionally, dolphins are negatively impacted by rising noise in rivers and net entanglement can also damage nets, causing economic losses.

That’s where pingers come in.

Mridul Kanti Kar, field researcher at WWF-India, deploys the F-POD – an underwater hydrophone that is used for acoustic monitoring of the Ganges river dolphin – at Harishpur on the Roopnarayan river. Photo: Mohd. Shahnawaz Khan.

A Sound Solution

The idea behind pingers is simple, yet well-designed: create a sound that dolphins can hear and instinctively avoid. These sounds – often in the range of 50 kHz to 120 kHz, are above the hearing threshold of most fish and humans but well within the sensitive hearing range of dolphins. We ran our pilot along the Hugli and Roopnarayan rivers in West Bengal, waterbodies that are still blessed with pockets of Ganges river dolphin activity. We carefully monitored the dolphin behaviour over two years using a combination of methods, including visual observations, passive acoustic monitoring, and tracking fish catch data.

The results gave us reason to hope. Nets equipped with pingers saw a significant reduction in dolphin interactions. Dolphins began to avoid the pinger-equipped nets. In fact, sightings within 20 m. of these nets dropped significantly – down to 21.56 per cent in the Hugli, and 68.70 per cent in the Roopnarayan.

Even better, the fishers didn’t suffer. In fact, catches stayed steady – if anything, there was a slight increase. We’re talking 10 grams of fish per day – nothing dramatic, but enough to show that the pingers weren’t driving the fish away. And fewer dolphins near the nets meant less damage to the gear.

Uttam Dolai, a local fisher on the Roopnarayan river, secures a pinger – an acoustic exclusion device – to the headrope of his fishing net as part of an ongoing experimental trial. Photo: Mridul Kanti Kar.

That, to me, is what meaningful conservation looks like: a solution that helps both species and people. We weren’t just trying to save dolphins. We were trying to rewrite the story so that everyone wins – fisherfolk, wildlife, and the rivers that bind us all together.

While there’s still work ahead, I’ve never felt more certain: sound can carry more than warnings. It can carry the future.

Community Voices: From Skepticism To Support

Initial reactions from the fishing community were mixed. No one had heard of pingers before. Some were skeptical and concerned that the devices would interfere with their catch or that they were being asked to shoulder the burden of conservation without any clear benefit. But over time, perceptions began to shift.

Through a combination of hands-on demonstrations and community engagements, the fishers began to see the value of the technology. As the dolphin-fisheries interface dropped, so did the chances of fish-catch depredation by dolphins and conflict with authorities. Fishers expressed increased pride in being part of a conservation initiative that respected both the dolphins and their knowledge of the river.

In the quiet village of Naliapur, nestled in West Bengal’s East Bardhaman district, lives Nimai Rajbanshi, a seasoned, 70-year-old fisherman whose life has been entwined with the waters of the river Hugli for over six decades. A veteran of the river fisheries, Nimai Da (as locals call him fondly) has seen the river change, not just in its flow, but in the balance of life it sustains.

"For us, it's a good thing if dolphins don’t die in our nets," he says. Interactions with river dolphins, he recalls, have always been part of daily life – a coexistence that once thrived in harmony.

About a decade ago, Nimai Da and his fellow fishers cast large, multifilament nets into the river. But as fish stocks began to dwindle, they shifted to smaller, cheaper, monofilament gillnets, a necessary adaptation to declining yields. Fishing, once a dependable source of income, no longer provides the same security. "There was a time," he said, "when the river had enough for all, the fishers and the dolphins alike." Dolphins, being natural predators, even helped improve catch quality by feeding on the weak and sick, a silent but valuable service.

But today, with fish becoming increasingly scarce, a subtle conflict has intensified. Both fishers and dolphins find themselves chasing the same shrinking resource. "Dolphins now often approach our nets, trying to snatch the fish caught in them," Nimai Da explained." This not only leads to accidental dolphin entanglements but also damages our gear and reduces our catch."

Yet, in the face of this growing friction, there might still be hope. Nimai Da and many from his community have participated in trials to test the effectiveness of pingers. "During the trials, we noticed that dolphins avoided the fishing nets with pingers," he shared. "That never used to happen before."

The promise of this technology is undeniable. The pingers could drastically reduce dolphin entanglements and protect both the fishers' livelihoods and the precious dolphins. But there’s a catch. The devices are expensive and hard to come by. "We’re eager to use them," said Nimai Da, "but making them affordable is key if we want to see wider adoption."

Towards A Scalable Model

The success of this pilot study has opened the doors to a larger conversation: Can pingers be implemented at scale across the distribution range of the Ganges river dolphin in the country?

The promise of pingers comes with its own set of challenges. Scientists still need to determine how many can be used without altering dolphin behaviour. Cost remains a barrier, these devices must become more affordable and locally manufactured to ensure wider access. Equally important is training fishers and recognising that every river and every community is different. We also need to conduct cost-benefit analyses to understand how pingers can lead to savings on net damage and how they impact fish catch. One solution won’t fit all, it must be tailored, thoughtful, and rooted in local realities.

Yet, the benefits are compelling. By reducing bycatch and preventing net damage, pingers help protect the endangered Ganges river dolphin. At the same time, by allowing fishers to maintain their livelihoods, they ensure that conservation does not come at the cost of economic hardship. This approach sets a precedent for how technology, traditional knowledge, and community partnership can work together to solve some of the most pressing environmental issues of our time.

Pingers are no silver bullet, but they’re an important part of a broader solution, alongside stronger policies, protection, sustainable fishing, science, conservation and community action. As their gentle pulses echo through Bengal’s rivers, they carry a message of hope: that fishers and dolphins can thrive together. In that sound, perhaps, lies a new rhythm for conservation in India.

Mohd. Shahnawaz Khan is Lead – Aquatic Habitats and Species, WWF-India. He has over 15 years of experience in aquatic biodiversity, specialising in integrating ecological research with community participation and protecting livelihoods. His work focuses on bridging scientific conservation with grassroots engagement, involving riparian communities as active partners in safeguarding key freshwater mammalian and reptilian species in the Ganga River System.