Remembering Patai Takaru - The Big Island

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 4,

April 2023

Dr. Manish Chandi has been associated with the Nicobar Islands for over 20 years now. He has closely observed and interacted first hand with the two Indigenous communities of Great Nicobar over many yearly visits for his research on their resource sharing and management strategies. In this essay, he takes us on a journey across the island, giving us glimpses of its people, forests and rivers, and all that is at stake just as ‘the big island’ is set to change forever.

Patai Takaru means ‘the big island’ in the southern Nicobarese language. Known to most of us as Great Nicobar, it is the largest among the more forgotten and marginalised islands in the Nicobar district of the Andaman Nicobar archipelago. Of all the attributes and unique features of Great Nicobar Island, the least studied and therefore the most misunderstood are its two Indigenous and aboriginal tribal communities – the Shompen and the Great Nicobarese. The Shompen are forest dwellers, said to have first arrived in Great Nicobar more than 10,000 years ago, and the Nicobarese, who live along the coast of the island, are a more plural community than the Shompen.

Like many adivasi people, these communities have engineered a self-sufficient and sustainable way of living, one that is perfectly suited to a tropical island. Newer generations are guided by their traditional values, rooted in the managing and sharing of natural resources; their belief systems that transfer their knowledge of the limits to the island resources; and their social structures, built to avoid conflict over those resources. I have been to their villages and settlements and seen them thrive. I have also seen their lives get upturned after the tsunami and worked with them to rehabilitate their new villages. I have been a witness to the slow transformations their traditions have been subjected to and the impoverishment their younger generations continue to suffer. As I write this piece, I am aware that 10 entities have shown interest in building a commercial transhipment port at Galathea, and I am taken back to where it all began for me. I am sharing my memories of my visits to the islands in the hope that these recollections will fill in some of the gaps left blank in the ‘holistic’ development proposal for the islands.

This outrigger canoe, referred to as reuii in the southern Nicobarese language, is made out of light wood, with a mast to fit a lateen sail; a distinct decorative frontispiece; and a tail that can distinguish one canoe from another. Photo: Dr. Manish Chandi.

The Beginning Of My Association

I arrived in the Andaman Islands mid-1995 as a conservation corps volunteer with WWF-India working alongside the Andaman Nicobar Environment Team (ANET), a former division of the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust. I visited Great Nicobar Island in 1996, to both witness the arrival of female leatherback sea turtles at Galathea Bay beach and to meet Dr. Ravi Sankaran, who had been studying the Nicobar Megapode. Accompanied by my friends Sohan Shetty and Arjun Shivsundar from the Pondicherry School of Ecology, we boarded the MV Sentinel, a rusty and slow-moving ship, and she chugged away over the beautiful blue waters, stopping at every island port that had a jetty to offload cargo and passengers. We reached Great Nicobar after a four-day long journey with fellow passengers and roaches for company, and the bracing sea breeze for comfort. Having secured our Tribal Area Permit from the Assistant Commissioner’s office, we headed to the Galathea river, the last stop of the State transport bus service. At point 41 (the number referring to the distance in kilometres by road from Campbell Bay), there was a narrow opening into the forest towards the creek, opposite to which was a signboard that read ‘Galathea Wildlife Sanctuary’. A makeshift bridge made of logs, tied with old steel cable and nylon ropes was laid across the calmly flowing river. A marshy littoral forest took us towards a pump house adjacent to the creek, with a small well where we would bathe and wash clothes over the next weeks. Beyond the creek was a patch of mangroves dominated by Nypa palms and Rhizhophora strands, and further ahead was the dense evergreen jungle. The small board along the path led to the beach where the Forest Department sea turtle monitoring camp was located. Thatched huts and one wooden building on stilts made up the camp, which was fringed by lush Barringtonia trees. The camp was in a clearing – clean, quiet and sheltered, or so it seemed (the tsunami of 2004 showed us how naïve we were).

The Nicobarese And Shompen Villages

The next day, we crossed the rickety bridge and walked till the 43rd km. to reach Chingenh – the only Great Nicobarese village that was situated on the east coast on the other bank of the Galathea river mouth. As we entered, we were met by the village Chief, or the ‘Captain,’ Mr. Sitaram. He took on this name beyond his own Nicobarese name about two decades ago through the acculturation process. He said that he wanted to be seen as an Indian, with a name easy for ‘sahibs’ to use. Captain Sitaram was an articulate and savvy man, well known among senior officers at Campbell Bay; they would always come to Chingenh when they wanted to see a Nicobarese village and Sitaram would show them around. His younger son Kimoss, a young boy then in 1996, went on to become the village Captain after the tsunami of 2004. We also met Mr. Mathew, a gentleman with severe filariasis, which impaired his mobility, who was skilled in carving model Nicobarese canoes and huts to earn an income. I bought my first Nicobarese canoe from him and it survived 20 long years. Referred to as reuii in the southern Nicobarese language, it is an outrigger canoe made out of light wood, with a mast to fit a lateen sail, distinct decorative frontispiece and a tail that can distinguish one canoe from another, which are often quite creatively named. These canoes are also revered and celebrated as cohorts in community and spiritual life among some of the Nicobar Islanders.

The village of Chingenh was a beautiful settlement of 15-20 huts along the Galathea beach, spread under the shade of coconut and a few areca palms. It sat between the forest and the coast, a pattern seen in nearly all Nicobarese villages across the entire archipelago. Captain Sitaram showed us around and took us into a home to have tea and a breakfast of barbecued fish and tender coconuts, cut into long strips. We were introduced to Kagaz and Rose, then young Shompen children who, I later learnt, belonged to the Kurshinom and Kirasis Shompen settlements (these Shompen villages are located in the forests, which are to be cleared for the associated infrastructure of the transhipment terminal). Captain Sitaram had adopted the children, though he did not claim any ownership over them. Sometimes Kagaz and Rose would go back to visit their bands in the jungle and return to Chingenh when they wished. Adoption of children is common among the Nicobarese community and not just for childless couples, but also as an inclusive means to help poorer families feed their children, and raise a village together.

Late Captain Sitaram of Chingenh village, at the 7th km. Campbell Bay, now called New Chingenh. He built this house despite being given a ‘permanent shelter’ by the government in the interior. A preference to live by the seaside is ubiquitous across the Nicobar. Photo: Dr. Manish Chandi.

Re Kayil – The Galathea River

We spent three days shuttling between Chingenh and the Forest Camp at Galathea Bay, where we witnessed the fascinating arrival of huge female leatherback sea turtles at night. The effort, strength and instinctive behaviour of these massive, but passive, wild animals that visit the shores only to lay their eggs is like a supernatural phenomenon we were lucky to witness. We decided to explore Re Kayil – the Nicobarese name for the Galathea river. We learned from Captain Sitaram that one can only go upstream to a certain length, after which there are rocky overhangs as the evergreen forest takes over from the estuarine mangrove regions. The three of us – Sohan, Arjun and I accompanied by one forest guard set out in a small fibreglass boat owned by the Forest Department. As we rowed up the river, dense thickets of the Nypa palm growing all over the banks obscured our view of the forest beyond. At several places, we could see gaps among the thickets that were the openings to the paths used by the Shompen to come to the river for fishing, and for Nicobarese as hunting paths into the forest. As we looked out for birds and wildlife, we were lucky to spot a few saltwater crocodiles – the largest predators of these dense riparian forests – before they vanished underwater. Being oblivious to their presence was better than knowing that their huge, strong bodies lay somewhere beneath our little row boat’s path.

We finally did meet with Dr. Ravi Sankaran, the first Indian to have studied the endemic Nicobar Megapode. He had set up camp further from Chingenh at the 47th km. along the coastal forest, in a space he called the den of megapodes. Ravi, gave us many pieces of advice, of which the first was, to introduce ourselves and take permission from each village Captain before conducting any work in the area. He said, “Remember, this is their land; their space and their rights matter more than ours”.

_C-1300_1680600124.jpg)

Kohoi, a Shompen man, who Manish met along the East-West Road. Men like Kohoi frequent the Tribal Welfare Department to collect rice, which they use as a supplement to their diet and also share amongst each other. The rainforests and water courses of Great Nicobar Island provide all their nutritional needs, which are hunted and gathered, as do small cultivation plots the Shompen maintain. Photo: Dr. Manish Chandi.

The East-West Road – A Walk To Remember

My second and one of the most memorable visits to Great Nicobar was later that same year. I took up the task of profiling the coastal vegetation of the island for a project under the United Nations Development Programme. Partly owing to the requirement of the task but mostly driven by my own desire to explore the forests of the island, I decided to walk. Armed with a red backpack with essentials such as a machete, umbrella, torch light, match box, water, rations and a few cooking vessels, I planned to walk along the East-West Road that passes through the centre of the island bisecting it into two halves and reach Kopenheat, a Nicobarese village.

I walked past labourers who were repairing the road, on to a path that cut through the jungle. I can still remember how green everything looked and how wet everything felt. I was enamoured by the sights and sounds around me. There were tree ferns all along the path and intriguing bird calls filled the otherwise silent surroundings. From time to time, the Nicobar long-tailed macaques sounded alarm calls, alerting other troop members of my presence. As I walked along the curvy road, I noticed the lajwanti (touch-me-nots) everywhere, growing so thick at some places that it poked my feet through the gaps in my sandals. I filled my bottle with pure, cool water from the brooks and streams along the culverts. I reached my first stop along the East-West Road – the Shompen ashram complex, which was meant for facilitating the exchange of items between people. I spent my night in the hall-cum-kitchen of the complex with the labourers who also ate and slept there. As I was about to start again the next morning after having breakfast, four Shompen men came in with some freshly caught shrimps and ate it with some rice and kukdi bhaji – the local name for an edible variety of ferns. The Tribal Welfare Officer, a lady called Shabnam, insisted that the Shompen men take me, their tamyon (the Shompen word for big brother), to Kopenheat to meet Makkan Buddhi and Mr. Vishwanath, leaders of the village. As we started, it became apparent that they were not keen to walk with me. Besides, I could barely keep up with their quick pace, with my luggage further slowing me down. By the time I trekked up the valley and came out onto the road, they had disappeared deep inside the forest and I was on my own again. As I walked on, I came across two to three bands of Shompen men, some returning with freshly caught eel, carrying fishing spears and others heading to the ashram for tobacco. All the groups would stop to examine my backpack and ask me if I had any tobacco. They were not interested in any of my belongings – some of which even made them laugh at me, for reasons I will never know. Upon not finding tobacco, they would leave and I would repack my stuff and continue walking. My comfortable walk along the cool shady road was interrupted at several places as the roads were washed out by landslides and rain that forced me to trek down the valley through the forest and trek up the road again where it was intact. Hours later that evening I could hear the sea and was happy to be reaching Kopenheat. But the path would still continue for a couple of kilometres, with no end in sight. Finally, I caught sight of the narrow beach. I was finally on the West coast.

Late Kagaz weaving a thatch roof to replace the tin roof of his permanent shelter at New Chingenh. Kagaz was a young Shompen man, who was partly raised by Captain Sitaram at old Chingenh from 1993. He lived both in the forest and at the settlement of Chingenh, illustrative of the fluidity among the two Indigenous communities of Great Nicobar Island– the Shompen and Great Nicobarese. Photo: Dr. Manish Chandi.

Kopenheat To Chingenh

My arrival at the beach startled two little girls who were playing in the sand, who ran towards their settlement. I was received by Mr. Vishwanath, who introduced me to others and took me to meet Makkan Buddhi. I stayed with them for a couple of days and collected information on the coastal vegetation. I did the same along each of the Nicobarese villages on the south west coast as I passed them – meeting people, noting names of the plants that were growing naturally as well as the ones that were being cultivated by the Nicobarese… and asking them for what purpose the plants were used. Moving southwards, I passed the villages of Koshindoun, Tenlet and Pulo Bhabi, which roughly translates to ‘the place with many pigs’. Pigs have a special place in Nicobarese culture. They are reared with great care, kept in designated places under the huts and only fed the choicest of coconuts. They are exchanged as gifts, used as barter and feasted upon during festivals and ceremonies. Pigs are a symbol of prosperity. Thus the village of Pulo Bhabi was considered prosperous as more pigs meant a lot of coconut trees and many able-minded people who would help in rearing the pigs.

Further down from Pulo Bhabi, I passed Kokeon and Pulo pukka, situated along Nanjappa Bay. Next, I walked through the Nicobarese villages of In Haeng loi, Pulo bha and Hingloi, located around Pemmaya Bay. Both villages are now demarcated for coastal tourism, institutions and port logistics. Next, I crossed Pygmalion point, better known as Indira Point, situated on the southernmost tip of Great Nicobar Island. The Nicobarese call the area Ku. According to their belief system, Ku is an unsafe place where an evil spirit and its cohorts reside and cause harm to whoever crosses by. Determined, I continued walking and finally reached Chingenh.

Great Nicobar is the only island in the entire archipelago with five perennial rivers. Both the communities use the river streams as sources of water and food. The forests and water courses have a special place in the cultural rituals relating to celebration, identity, births and deaths of both the communities. Photo: Dr. Manish Chandi.

The Southern And The Northern Great Nicobarese

After the two visits to Great Nicobar in 1996, I spent the next couple of years working in the Andamans. In 2000, I revisited Nicobar, driven this time, to understand how the Nicobarese utilise resources on the island and how they differ from one island to another. As I started mapping the settlements and place names used in various villages, it became apparent that there are not one but two linguistically and culturally distinct groups of Nicobarese living in Great Nicobar. Beginning from the village of Pulo kunji located almost on the centre of the West coast till the southernmost village including Chingenh on the East coast, where the Nicobarese language was in use, the people can be grouped as the Great (southern) Nicobarese or Payuh patai takaru. While northwards from the village of Pulo Bed, Rekoret, Renhong, Re maun, Afra Bay, Kondul and Pulomilo islands and all of Little Nicobar Island, where the language of the Little Nicobarese is in use, the people can be grouped as the Little Nicobarese of Patai ta-bhi (Little Nicobar). Both have their unique dialects of the Nicobarese language, and variations in their social and cultural practices. They do intermarry and some also identify common ancestors from both groups. Despite this, their territories and land ownership are unique to each group.

The Indigenous people of Patai Takaru

The Shompen, approximately 250 in number, are nomadic hunter-gatherers and horticulturists who live in groups or bands of 20-50 persons in the interior forests and along water courses. They harvest wild pandanus fruits; hunt animals, various fish and saltwater crocodiles; and grow chillies, lemons, taro and tubers. The Great Nicobarese are a coastal islander community who herded pigs and chicken, whilst cultivating coconuts, areca nuts and a few tuber crops too. A large part of their diet includes pandanus and sea food and they are expert craftsmen, their skill visible through the type and variety of huts they build from natural materials that are perfectly suited to the local climate.

Before the 2004 tsunami, they were distributed along the southern and south western coast of Great Nicobar Island across 11 villages. Today, they are an internally displaced community, about 420 in number, making them the smallest of all the Nicobarese sub-groups of the Nicobar Islands. The nine survivors of the tsunami along the west coast were united with the rest of their community members, some who were in hospital or visiting friends, or working, studying elsewhere beyond their homes. They are the last of their once larger islander community.

Many families of retired military personnel were settled here by the government; other mainlanders followed over the years for farming, business, construction, etc. They look forward eagerly for a better livelihood and employment opportunities. The Indigenous tribes and settlers are very distant from each other culturally in their desires, needs and outlook for a future on the Big Island.

The 2004 Tsunami And Its

AftermathOn the day of the tsunami, December 26, 2004, close to 250 members of the Nicobarese tribe living along the west coast perished. Only nine survived. Those nine people, four men and five women survived on their own for 35 days, after which they reached and crossed the Galathea river. A team of us who were looking for survivors found them there and got them to Campbell Bay for treatment and to begin life anew. These surviving members of the Great Nicobarese tribe were relocated by the Andaman administration after the tsunami to ‘safe ground’ at Campbell Bay, the headquarters of Great Nicobar Island and the Southern Nicobar administrative division. They continue to live in two settlements in Campbell Bay – Rajiv Nagar and New Chingenh, that were supposed to be temporary, as they wished to go back to their ancestral lands. But the Andaman administration wishes to make them permanent settlements for their administrative convenience. Their appeal of 18 years to be resettled in their pre-tsunami villages has been ignored and shaded by unkept promises of the Andaman Nicobar Administration. They have lived in desperation for nearly two decades, working as manual labourers to earn an income in the shanty town of Campbell Bay – in many ways, they are strangers in their own land of Patai Takaru. Their distress and discomfort can be seen in many fighting alcoholism, traumatic stress from their displacement, and a lack of acceptance by the mainlander population who have no sensibilities of their island life and just identify them derogatorily as ‘holchu (Nicobarese word for friend) tribal’. Many in the remnant community suffer from depression due to being displaced, and from various other ailments on account of changed diets and sources of nutrition, and an inability to perform what they see as their normal duties, which would lead to a peaceful, happy livelihood. The despair can be seen in the cemented pathways leading to the ‘shelters’ built for them by the government after the tsunami. Cracked, broken and washed away by incessant rain, slush and litter of the high ground and a lifestyle eked out from ration supplies and snack shop goods in Campbell Bay. They don’t own their own coconut, areca or banana plantations and are forced to be dependent on the cash economy rather than their own, which was a mixture of barter, their own labour and of sharing of natural resources and produce amongst kinship groups and friends. At Campbell Bay, they indeed are strangers in their own land.

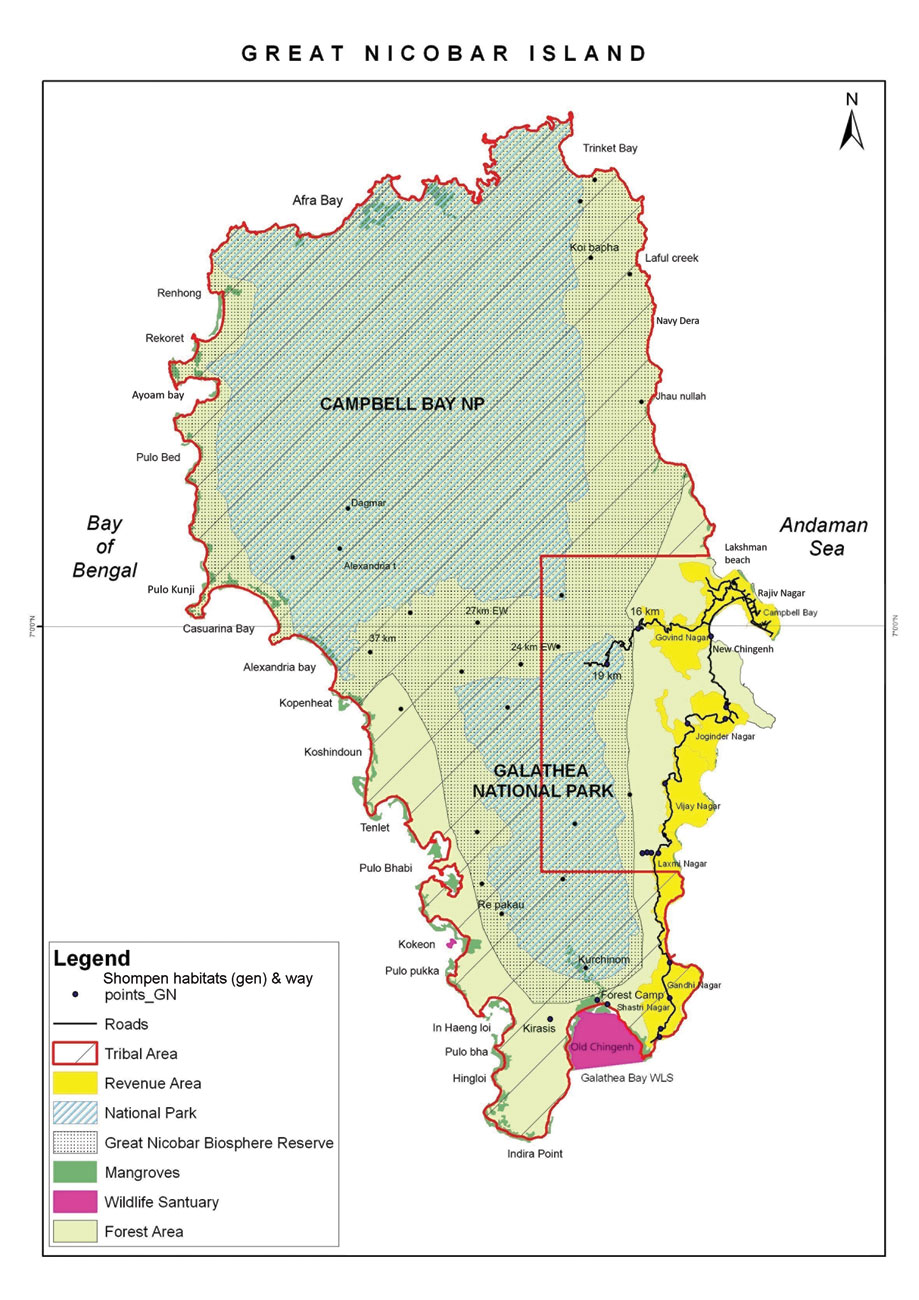

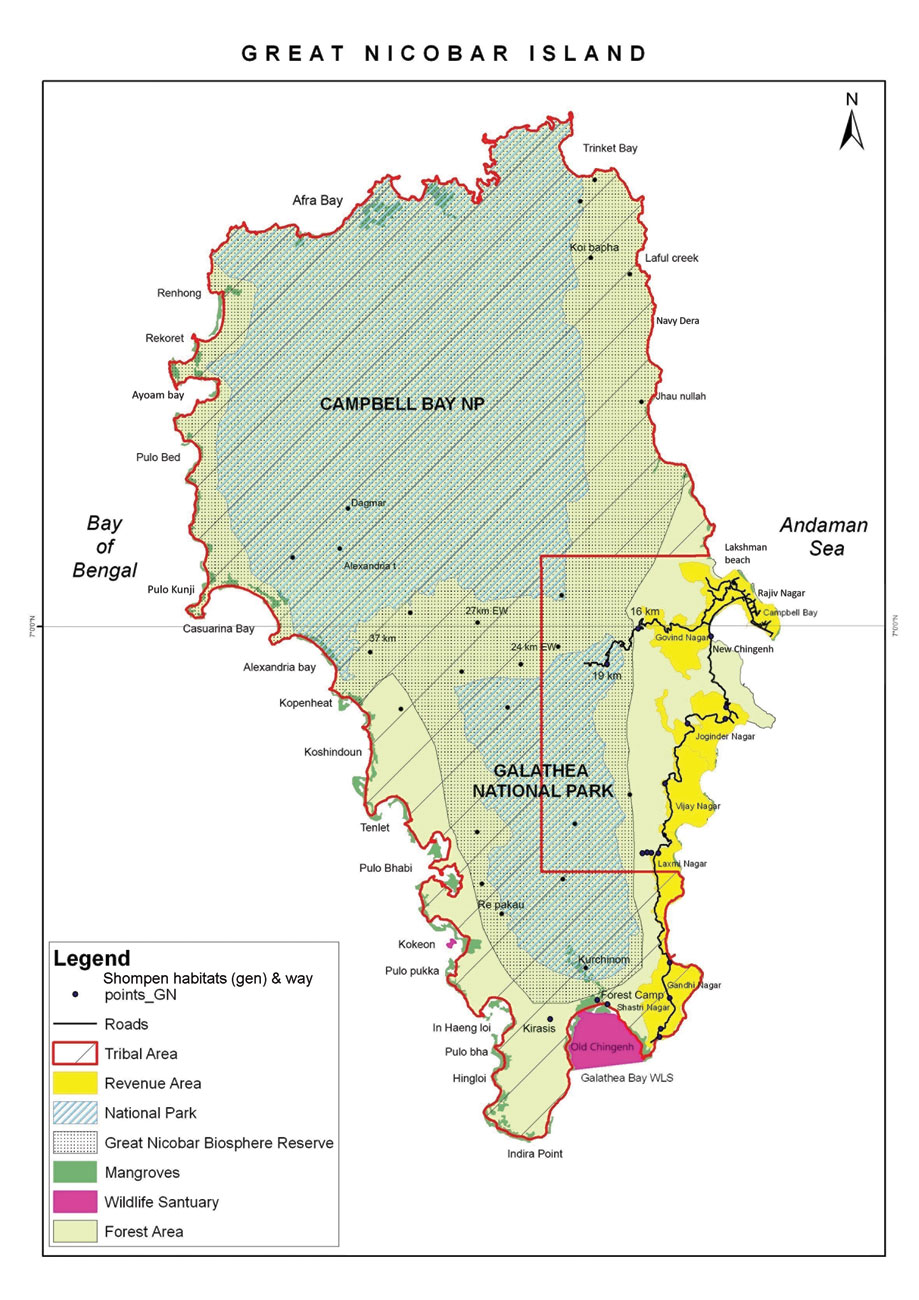

Map of Great Nicobar Island showing the prevalent land use pattern. The coast from Galathea Bay (south-east), along the entire western, northern and part of the north-east coast close to Campbell Bay, was originally reserved for the Indigenous communities. Photo Courtesy: Dr. Manish Chandi.

Spirits of the forests and friends of the sea

According to a belief, there is a black stone in the forest which is alive – they call it tirah. Making sounds near the tirah by cutting trees or shouting leads to high fever, bloody vomit and eventually, death. There is a tree called chat-mat in which a spirit resides, and anyone who tries to chop its branches or cut it gets swollen eyes and chicken pox-like spots all over their body.

The Indigenous islanders have many stories featuring various animals they share spaces with. According to one story, a wild pig and a girl got trapped underground and continue to live there. When the spirit of the pig cries or gets angry, it causes the ground to shake and earthquakes are caused.

They have many beliefs involving marine species. For instance, hunting a hipot (dugong) causes storms and cyclones. Hunting a kapoaak (dolphin) is a sin. They are equated to human beings as they are very smart. It is said that in earlier times, when someone was lost at sea, dolphins would bring them back to the shore. The hikunth (leatherback turtle) is only consumed by elders as its meat is believed to have anti-ageing properties. The meat of the kao kayil (hawksbill turtle) is to be eaten with great care as it may be poisonous, depending on the algae it feeds on. It is believed that if a pregnant woman or a member of her family consumes it, the child will be born with a deformity.

What The Port Project Gets Wrong About The Tribes

My most recent visit to the island in 2018 was to prepare a report on the stakeholders’ opinion about the development project, which was commissioned by NITI Aayog. Together with anthropologist Dr. Vishwajit Pandya and film-maker Anirban Dutta Gupta and members of the Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), we visited and interacted with members from all communities on the island. While the Little Nicobarese were not in opposition to the development plan, they were clear that they did not want tourism as they enjoy their peace and quiet on their own terms and were not in need of income by selling their culture and vistas to outsiders. The Great Nicobarese on the other hand were despondent. They were looking for a better life after the devastating tsunami of 2004, and hoped that despite the enormity of loss in lives of their kin, their traditional coastal lands and resources, they would one day return to their ancestral lands and the sound of waves washing their shores, to grow coconuts, rear pigs and chickens, and find fresh fish from the reefs off their village coasts.

Though, the administration and project proponents have assured that the Great Nicobarese will be relocated once the roads are built, crucial information regarding the locations of the proposed projects have been withheld. The Nicobarese still believe they will return home. Their ancestral spirits guard those lands in their absence, and they await the time when they can return and walk those sandy beaches without having to live a life that has been forced upon them. The government should listen to and learn from the Great Nicobarese about Great Nicobar, Patai Takaru, which is more than its naturally occurring deep drafts, and proximity to a trade route. It is the last among the few places left on the planet where people are not separated from nature, but are a part of it. It is the only home of two cultures who have mastered sustainable living before it became a catchphrase for development projects. But would the voices of the payuh of Patai Takaru matter? Or will the Great Nicobar Transhipment Port be built over the ashes of their ancestors?

Dr. Manish Chandi completed his doctoral thesis on understanding how resource sharing mechanisms are an integral part of natural resource management in the Nicobar Islands from the Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysuru. He has worked for long with the Andaman Nicobar Environmental Team as a researcher in Human Ecology and as Field Director.

_C-1300_1680600124.jpg)