One Million Snakebites

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 37

No. 6,

June 2017

By Janaki Lenin

If you are a young farmer in India, your chances of succumbing to snakebite are greater than anywhere else in the world. The country has made impressive strides in several fields, including putting satellites in orbit, but in the case of snakebite casualties, we appear to be mired in the Dark Ages.

According to earlier reports from the World Health Organisation (WHO), between 35,000 to 50,000 Indians die of snakebite every year, but in 2008, the government reported a dramatically low 1,400 snakebite mortalities. In 2015, the number plummeted even further to less than 1,100.

A path-breaking project code-named ‘The Million Death Study’ (see box) provides the first realistic handle on the impact of venomous snakes. By a process of extensive interviews called ‘verbal autopsies’, the study found that snakes bite as many as a million Indians every year while almost 50,000 people die, a third of globally-estimated snakebite deaths. In other words, for every two people who succumb to AIDS, there is one snakebite victim!

Snakebite Prone?

Indians seem quixotically prone to high snakebite-risk behaviour such as walking barefoot without a torchlight at night, sleeping on the floor, and creating ideal cover for rodents and snakes in their midst. Once bitten, they further reduce their chances of survival by going to a witch doctor first, rather than seeking the only cure, antivenom, from a hospital. There is very little understanding that a snake injects its virulent muscle-eating, nerve-damaging, blood-destroying venom deep into body tissue that no amount of superficially-applied ‘black stones’, herbal poultices, or eating bitter roots can hope to counter. For decades, Indian herpetologist Rom Whitaker has evangelised that only an injection can counter the snake’s injection, but clearly vast areas of the country remain to be educated. Rom is now the Project Manager (India) of the Global Snakebite Initiative.

Across south Asia, picture-perfect rice fields are highly-productive food bowls of nations. Whitaker, however, sees them as ideal snake-rich landscapes. The flooded fields demarcated by raised embankments create perfect conditions for much higher densities of rodents and snakes to thrive compared with natural forest landscapes. For nocturnal, rodent-eating, farm-living snakes, life can get no better. At dusk, cobras emerge from the rat burrows to bask in the setting sun when barefoot farm workers are likely to step on them. This, plus walking in the dark without lights is when the bulk of snakebites occur.

In his film for BBC Natural World One Million Snakebites (now dubbed in Tamil, Hindi, Bengali, Kannada and Marathi), Whitaker used high-speed photography to demonstrate that despite the bad rap, the cobra doesn’t bite most of the time. It first tries to avoid confrontation by making a quick getaway. When cornered, the defensive snake sits with its hood spread, looking beautifully dangerous. In take after slow-motion take, every cobra strikes with its mouth closed, its dangerous toolkit sheathed, ‘punching’ a warning but not biting. Now you know why Rikki Tikki Tavi, the mongoose, always wins its bouts with Kipling’s hooded death. It is surmised that the cobra is reluctant to bite because producing venom demands a lot of energy, and no snake in its right mind would want to physically tangle with an animal as deadly as a human.

Even the small, feisty saw-scaled vipers and the larger, stout Russell’s vipers are prone to swift departure in some cases. But in others, they open their jaws wide and sink their fangs up to the hilt.

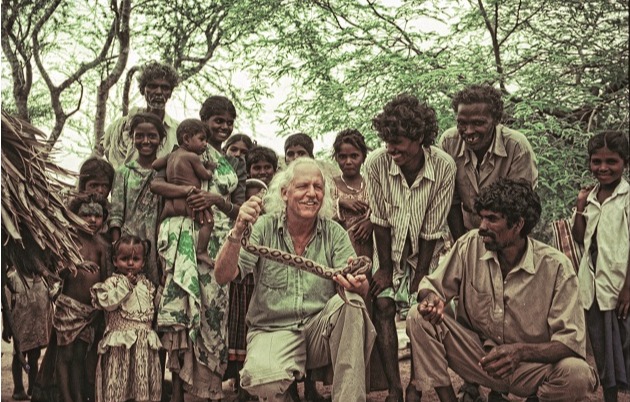

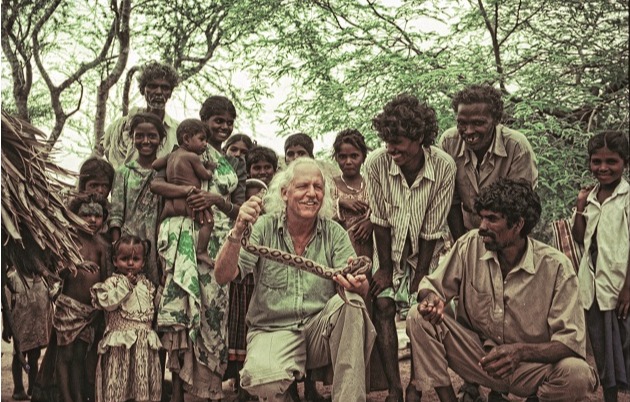

Herpetologist Rom Whitaker has worked with Tamil Nadu’s snake-tracking Irula tribals for more than four decades. He currently serves as Country Project Manager, Global Snakebite Initiative. Photo Courtesy: Janaki Lenin

Herpetologist Rom Whitaker has worked with Tamil Nadu’s snake-tracking Irula tribals for more than four decades. He currently serves as Country Project Manager, Global Snakebite Initiative. Photo Courtesy: Janaki Lenin

Healthcare Quality

The Million Death Study found that rural Indians suffer 97 per cent bites but only 23 per cent of the deaths occurred in a hospital – another reason for the very low, official snakebite toll figures. Even the Irula tribals, with whom Whitaker has had a long collaboration, set great store in their native treatments. In one gory episode in the film, the swollen finger of an elderly Irula lady, who had been bitten by a saw-scaled viper, is sliced with a broken piece of glass and the whole hand packed with green plant material. Had it been a lethal dose of venom, the outcome would not have been happy. Belief in herbal medicine and magic is high in rural India and when the condition of such a patient takes a turn for the worse, he or she is belatedly rushed to a hospital. Doctors have a hard time distinguishing the symptoms of snakebite from complications caused by local treatment, thereby losing critical time. This is compounded by people’s poor knowledge of appropriate first-aid measures. For instance, wrapping tight tourniquets causes more harm than good.

The antivenom that is manufactured in India is of low potency and only made from the venom of four common species... though the country is home to several other venomous snakes. Photo Courtesy: Rom Whitaker.

Even if snakebite victims and their families choose to seek treatment from a hospital, not all of them stock antivenom. The patient may have to be transported over long distances to reach one that can treat him or her, and unfortunately, ambulances only service a small part of our rural areas. Some doctors rely on anecdotal mumbo jumbo such as the pattern of the bite mark and number of fang punctures to differentiate between venomous and non-venomous bites. Other problems include administration of insufficient doses of antivenom and lack of supportive care — such as ventilators to counter nerve-paralysing krait and cobra venom and dialysis machines to treat kidney breakdown from Russell’s viper bites. On top of this, antivenom manufactured in India is of low potency and huge doses may be required to neutralise the effects of venom. Whitaker collected a venom sample from one black cobra in Rajasthan that yielded 198 milligrams, while one 10-millilitre vial of antivenom can only neutralise six milligrams of venom.

There is an additional whammy: the venom of some species of snakes varies from one region to another. For instance, the venom of Russell’s vipers of east and south India are nerve-affecting in addition to the blood-deranging effects elsewhere in its range. This might mean that the antivenom made using the venom of south Indian Russell’s vipers is less effective against a bite from the same species in parts of north India.

Besides, antivenom is made from the venom of four of the most common snake species: spectacled cobra, common krait, Russell’s viper and saw-scaled viper. However, India has four species of cobras, eight species of kraits, two sub-species of saw-scaled vipers and one species of Russell’s viper. We do not know how effective the available antivenom is against the venom of all these species. Whitaker travels across India collecting venom samples from different species of snakes. Collaborating with toxinologists who work in the laboratory, he hopes to answer these complicated questions to produce a truly life-saving antivenom that is widely available and is effective throughout the country.

Why do Snakes Especially Target Indians?

Cobras, kraits, and vipers are common to most south Asian countries. Surely our neighbours who share the same farming patterns, lifestyles, and medical practices are equally doomed? Or could it be that there are just too many of us crammed on a land where agriculture is still the majority occupation?

Both India and Sri Lanka have about 300 people per square kilometre, while Pakistan has 214 and Nepal 200. But Bangladesh blows us all off the south Asian density chart with 1,100 people compressed into every square kilometre. It stands to reason that Bangladeshis are more likely to trip over snakes than Indians. And they do. A recent survey reported 700,000 snakebites and 6,000 deaths a year.

The best way of comparing these figures is to look at bites in units of 100,000 people. India’s five deaths per 100,000 people a year is high compared to the south Asian average of one to two per 100,000. Despite its high human density, Bangladesh suffers 3.85 snakebite deaths per 100,000 people per year. In Pakistan and Nepal, relatively low population-density countries, 4.5 and 3.7 per 100,000 people die because of snakes. Surprisingly, Sri Lanka’s human density figures are almost the same as India’s but it suffers a mere 2.3 deaths per 100,000 people. This kind of back-of-the-envelope comparison is interesting but needs fine-tuning when better snakebite statistics become available.

The Million Death Study provided another clue to India’s snakebite problem: religion. A Hindu has a higher chance of dying from snakebite because his or her reverence for cobras has fostered a higher degree of tolerance toward the presence of snakes as well as a belief system that sets great store in village cures. To add a pinch of salt to that theory, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ranks second in severity in south Asia, not the Hindu nation of Nepal. More than religion, perhaps cultural practices doom people of the subcontinent.

At every turn, a poor snake-bitten farmer is conspired against – by his own occupation and behaviour, the snake’s potent venom, and the insufficient medical care delivery system. Solving this, the worst public health crisis caused by a vertebrate animal, needs a radical change: large-scale public awareness campaigns, clinical training and good quality antivenom freely available to all. Adequately covering the feet and ankles where most bites are inflicted, sleeping on cots and under mosquito nets will also greatly reduce the incidence of snakebite. Keeping the immediate surroundings clear of garbage, firewood piles, and straw heaps will discourage both rodents and snakes. Using a torch and being aware of snakes when walking at night would probably halve snakebite mortality.

In Madurai, a group of voluntary snake rescuers provide rapid transport to a hospital for snakebite victims. They also counsel patients and help in obtaining prosthetic limbs when a snakebite victim is disabled. In the Nepal terai, where the road network is rudimentary, volunteer village-based motorcyclists have proved effective in transporting snakebite victims to medical care. Programmes like this must be scaled up to enable victims to live as full a life as possible.

On the medical side, monitoring of incidence, mortality, and disability rates is important so improvements in dealing with the problem can be tracked. Rural health workers and doctors not only need training to adequately diagnose and treat snakebites, they also need access to antivenom and a range of basic resources such as ventilators and dialysis machines. Of course, venom and antivenom manufacturers need to work to WHO standards.

We have the knowledge and the technology to make all this happen; all the government needs do is push the concerned departments into high gear. A public awareness campaign that employs the best techniques of the advertising industry should educate people on how to avoid snakes and highlight that antivenom is the only antidote to a venomous snakebite. The Madras Crocodile Bank has begun an ambitious project, headed by Whitaker, with CSR support from USV Pvt. Ltd., Infosys Foundation and Deshpande Foundation. He has roped in key stakeholders in education, herpetology, medicine, toxinology, venom collection and antivenom manufacture under the banner ‘Living with Snakes’, so there is light at the end of this horrendous tunnel.

The Irula Snake Catchers’ Industrial Cooperative Society harnesses the skills of the Irulas to catch snakes, and extract venom to supply to antivenom-producing laboratories. Their facility is hosted within the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust. Photo Courtesy: Rom Whitaker

The Irula Snake Catchers’ Industrial Cooperative Society harnesses the skills of the Irulas to catch snakes, and extract venom to supply to antivenom-producing laboratories. Their facility is hosted within the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust. Photo Courtesy: Rom Whitaker

The Million Death Stud

The path-breaking project ‘The Million Death Study’ is providing key information on the impact of venomous snakes. Based on interviews, the study has uncovered that death due to snakebites is no small matter – with close to 50,000 people dying each year. Check this link for details:

Snakebite Mortality in India: A Nationally Representative Mortality Survey

The research team behind ‘The Million Death Study’ comprises clinicians from institutions in Canada (the Centre for Global Health Research at St. Michael’s Hospital and University of Toronto), U.K. (Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford) and India (the Registrar-General of India (Delhi), S.C.B Medical College (Odisha), Indian Institute of Health and Family Welfare (Hyderabad), St. John’s Research Institute (Bengaluru), National AIDS Control Organisation (Delhi) and herpetologists at Madras Crocodile Bank Trust (Tamil Nadu).

The videos produced by the Madras Crocodile Bank in English, Hindi and Tamil (so far) with the support of the Infosys Foundation, VINS and Bharat Serums are already available on YouTube. Check these links:

Four Deadliest Snakes of India,

Snakebite