Meet S.E.H. Kazmi and Raza Kazmi

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 4,

April 2021

Sanctuary’s Lifetime Service Award winner of 2016 S.E.H. Kazmi, spent much of his life protecting the forests of Palamau and Hazaribagh. His son, Jharkhand-based conservationist, wildlife historian, storyteller, and consultant at Ashoka Archives of Contemporary India, Ashoka University, Raza Kazmi grew up in the lush forests of eastern India. He was witness to the trials and tribulations of a forest officer’s life and saw how his father, bravely stood up to insurgency and bureaucratic challenges in Jharkhand (then in Bihar) to resurrect the Palamau Tiger Reserve. In this informal interview, Bittu Sahgal speaks to the father-son duo about their inspirations, influences, the dismal situation in Hazaribagh and their hopes for the future.

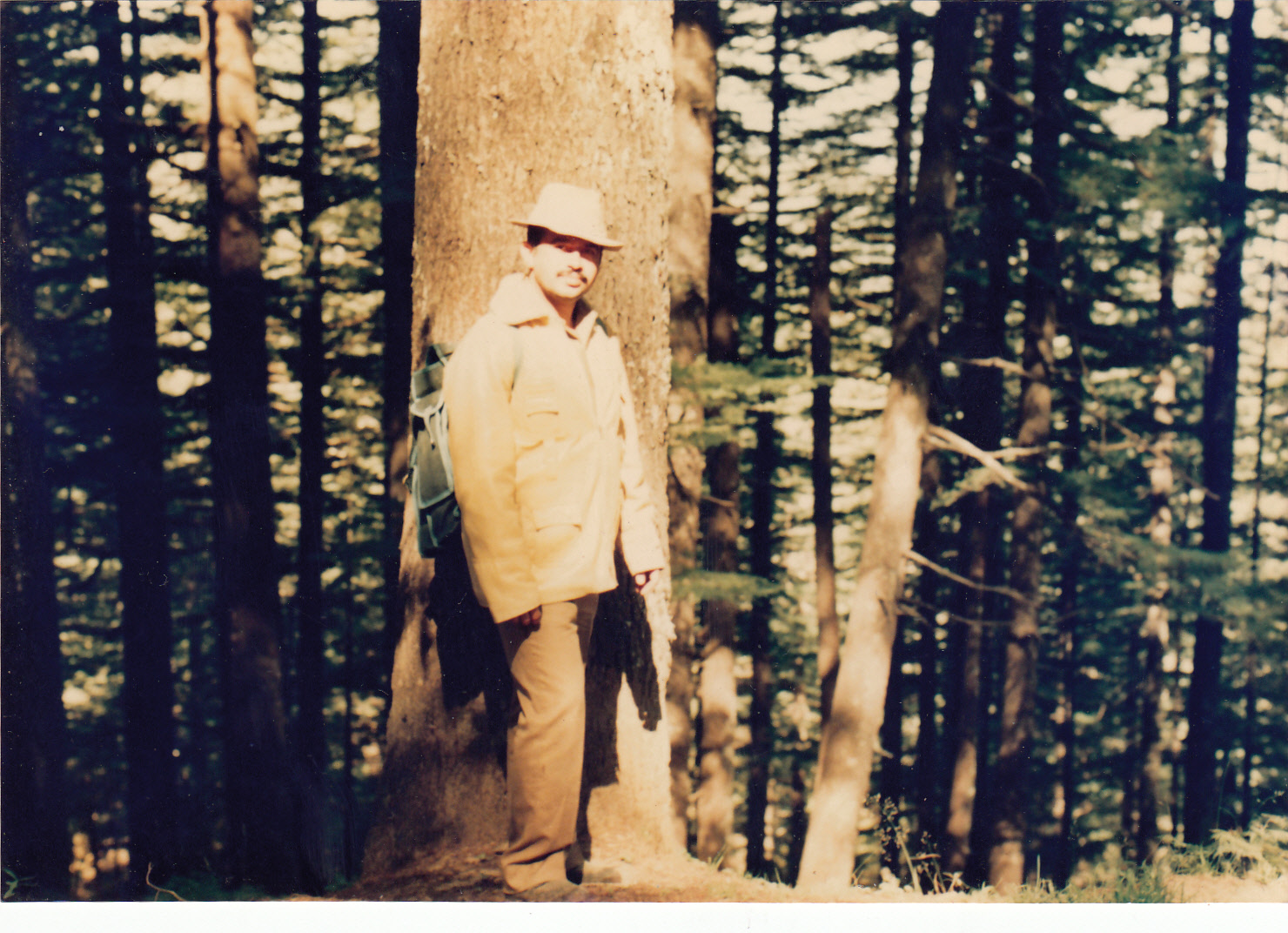

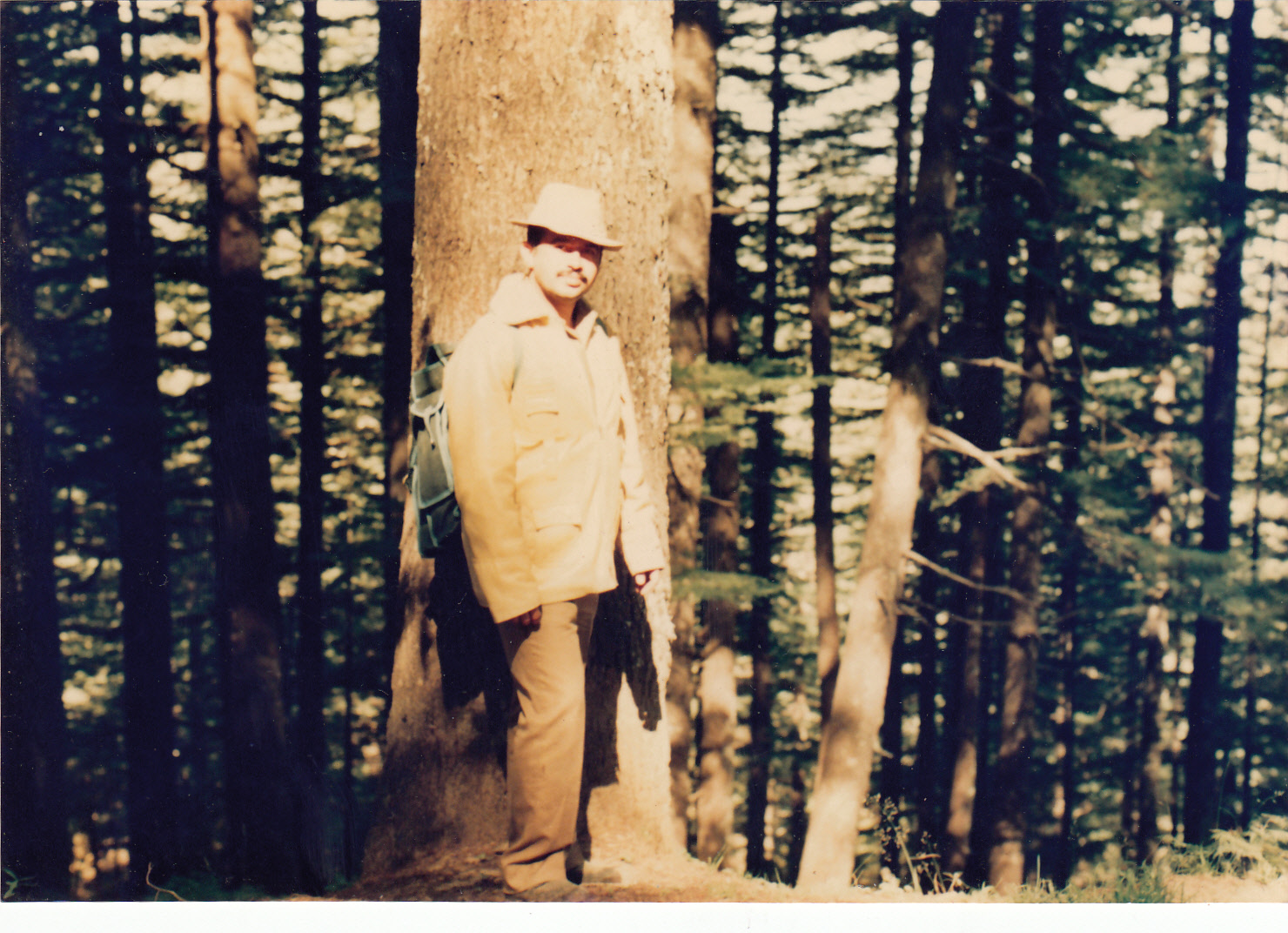

S.E.H. Kazmi at Kanasar, Uttarakhand during the ‘Hill Tour’ of his IFS Training Years, in 1985. Photo courtesy: S.E.H. Kazmi

What in your formative years prompted you to care for and struggle to protect wild nature?

Raza: That is an easy one. Undoubtedly, the forests of the Palamau Tiger Reserve and my parents, especially my father, influenced my love for the wild. One of my earliest memories is when I was around four years old, tagging along with my father and his team to douse a forest fire in a hilly part of the tiger reserve. I have distinct memories from that day. It was searingly hot, smoke billowing from the hill slope and charred vegetation. I remember a smoldering tree with its hollow still burning red, perhaps the nesting place of some animal. I had walked the entire day with Abba and his staff. Nobody carried potable water back then, so I remember drinking water from a drying pool in a forest nullah by digging the moist sand to make a chuaan (you dig a small saucer-like shape in the sand and water percolates from below to collect, a method used by locals and wild animals alike, especially elephants, in Palamau). I did get the runs afterward due to that

not-so-clean water, but that was all part of the adventure. That entire event had a profound effect on me. Abba would take me along in the forest whenever he could. My mother loved the forests too, so the entire family usually spent the weekend (and sometimes longer) together in some remote Forest Rest House. Abba not only instilled in me a love for the forests and wildlife of the region, but also the people who lived in and around here. He would encourage me to mingle with the villagers and our daily wage forest staff, and observe and understand their lives, hardships, struggles, joys, and sorrows. I would get to hear plenty of stories from villagers and our trackers who were quite happy to share these tales with a curious kid barely six or seven years old. Of course, later years at Hazaribagh and elsewhere had their impact as well, but nothing will match up to those memorable years in Palamau until 1998. This is what sealed my life’s goals for me, to work towards the conservation of these natural spaces, and wildlife. Observing wildlife has given me endless hours of joy, and the well-being of people who depend on them is vital for me. Perhaps that is why, even more than two decades later, I keep returning to Palamau as my forest home.

S.E.H. Kazmi: I was born in old Lucknow city where there were a lot of open spaces near the Jama Masjid. Every day I had to walk two to three kilometres to my school and along the way, there were agricultural fields and a nullah, which led to the Gomti river. My four-year-old mind run amok and spun wild imaginative stories of how I was a great explorer and hunter and the agricultural fields and Narkul grass Phragmites karka was a jungle with all kinds of exotic wildlife. In reality, there would be an occasional jackal, mongoose, hare, snake or small fish and frogs in the nullah. I would also eagerly await the summers for our annual visits to my ancestral village Rasoolpur in Barabanki District. My father, a teacher, retired when I was 10 years old and I was delighted when the family decided to shift to Rasoolpur. Then, the village had 60-70 households. There were old orchards of mango, guava and fallow land covered with pataavar grass Saccharum munja and bushy clumps of ber. I would roam around with the village boys grazing their goats and look out for wolves, which were quite common around Rasoolpur back then (in fact I distinctly remember seeing a wolf from the window of our house once). I was often scolded for not studying and roaming with the charwahas (grazers). “Tumko charwaha banna hai kya?” I was admonished. I collected quills of porcupine and kenchul (shed skin) of snakes. Then there would be bichkhopad (monitor lizard) jungli teetar (Grey Francolin) and bater (Jungle Bush Quail), and their chicks as well as chaugda/kharha (Indian hare), which were aplenty. A fox used to den in the outhouse and often teased and fooled around with our house pet dog. Blue bulls were around often. That is how I grew up.

During S.E.H. Kazmi’s tenure at the Palamau Tiger Reserve, it saw a tremendous revival, mainly on account of his involvement of local communities in conservation efforts and his persevering spirit to save this wilderness. Photo: Raza Kazmi

Who were your primary inspirations and what drew you to them?

Raza: Oh, there are many. Obviously, Abba is right up there at the top and I could write pages upon pages on his qualities and accomplishments that have inspired me. But to sum it up, it would be his honesty, integrity, politeness, compassion for people, especially those from the marginalised sections of the society, love for forests and wildlife, humility, and the fact that despite all his work he never took himself too seriously. Amma shared his love for forests and wildlife and made sure that all my formative days in the forest were spent together as a family. She encouraged me to follow my heart and was always my biggest cheerleader. Apart from family, I have been lucky to have received the guidance, mentorship, and friendship of some amazing people such as Prosenjit Das Gupta sir, Divyabhanusinh sir, Professor Mahesh Rangarajan, M.K. Ranjitsinh sir, A.J.T. Johnsingh sir, Bulu Imam, Anne Wright, Aparajita Dutta, Nandu ji (a daily wage forest tracker in Palamau, my friend, guide and teacher) and so many more. You, Bittu sir, gave me my first break at writing and have always encouraged me and I can never repay that debt. And then there are so many incredible people from the past whom I never met but have inspired me from F.W. Champion to S.P. Shahi, J.W. Best to Sálim Ali, S.R. Choudhury to Kailash Sankhala. I wish I had more space, I could name so many amazing people both from the past and present who have inspired and influenced me.

S.E.H. Kazmi: A turning point for me was after I passed 10th grade. My elder sister took me to Jaipur. I was not very academically inclined and once while having lunch I casually bemoaned that had I studied in an English medium school or received proper education, I would have tried for the Indian Forest Service. My brother-in-law, S.H.H. Kazmi, caught my hand and said that if I had the courage to study and take the exam, he would support and fund my expenses. He did not allow me to eat my “newala” (the food in my hand) until I promised to do so. It took three attempts and seven years and doing all kinds of jobs in between before I succeeded. After failing my second attempt, it was a do or die situation for me. In that last year of preparation, I was once studying in the University of Rajasthan’s library and came across an issue of Sanctuary magazine where I found the late Director of Project Tiger Kailash Sankhala’s address. It was a hot afternoon in April and I cycled about seven to eight kilometres to reach his house in 20 Dhuleshwar Bagh. He was surprised to see me and after gulping down a glass of water, I told him my story. He listened patiently, and said that I was the kind of person the Forest Department needed. He added, “Go and study and you will get through this time.” He assured me that even if I didn’t make it he will take me in as his field assistant in a project at the Desert National Park. His encouraging words were what I needed and in my last attempt, I passed through the written exam and interview in which to the question on what I had been doing all these years, I honestly replied that I had been trying to get through this exam.

Ultimately, it was my love for outdoors and adventure and sense of duty, which prompted me to compete for IFS and perform my mandated duties in letter and spirit.

I also enjoyed reading wildlife books. I really liked The Wild Life of India by E.P. Gee, Bwana Game by George Adamson, Born Free and Forever Free by Joy Adamson. And of course, Jim Corbett’s books. The work and life of these people impressed and influenced me.

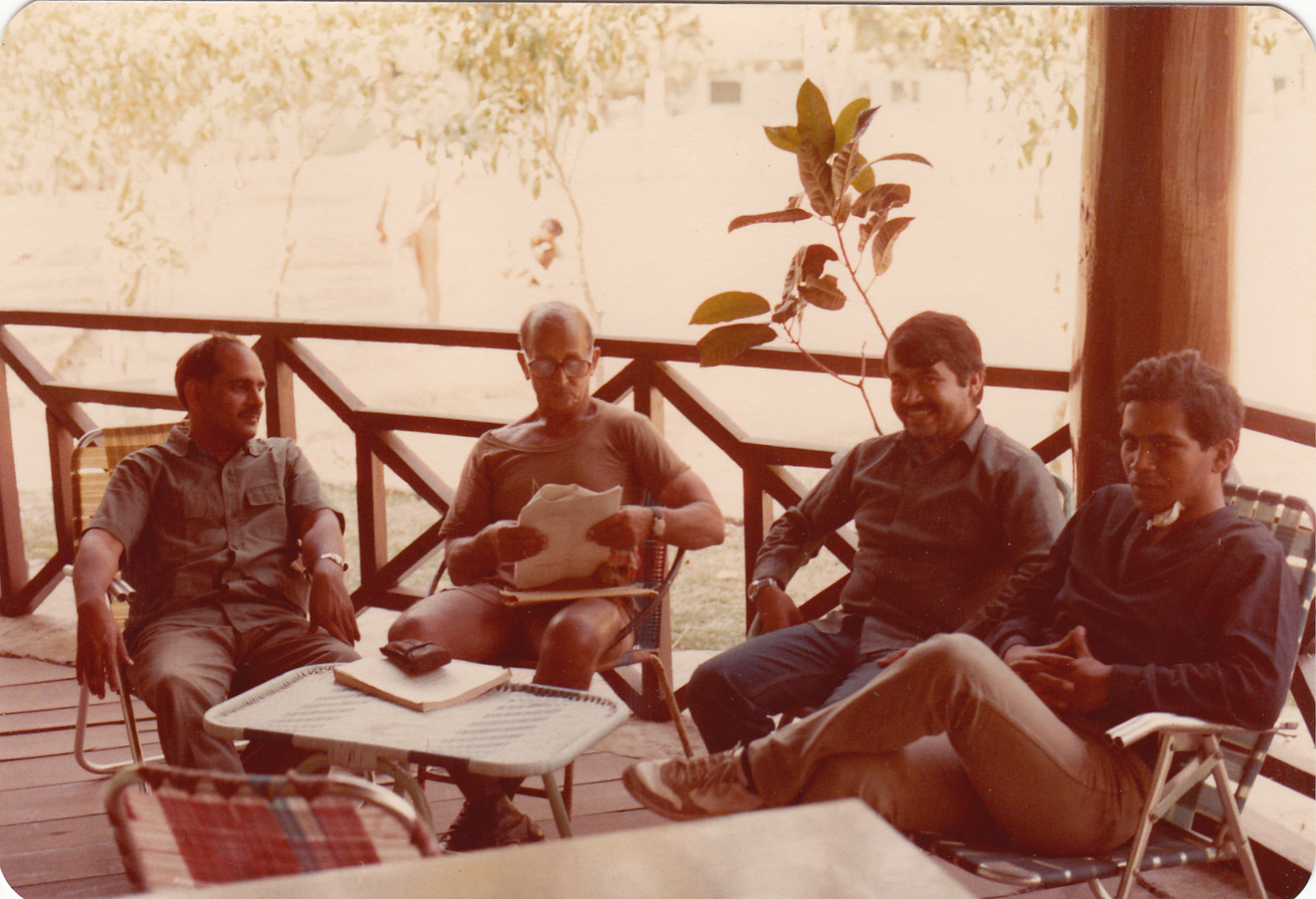

(Left to right) Gyan Chand Mishra (Field Director, Dudhwa Tiger Reserve), Billy Arjan Singh, S.E.H. Kazmi and R.K. Srivastava (retired as Director of Project Elephant) at Tiger Haven, Dudhwa, in 1986. Kazmi and some of his batchmates had taken off from the IFS training academy (then IFC) at Forest Research Institute of India, Dehradun on an unsanctioned leave to meet Billy. Photo courtesy: S.E.H. Kazmi.

What is the state of the Hazaribagh ecosystem and what will it take to protect it from coal and apathy?

Raza: I would be lying if I say that I see things changing for the good anytime soon. There seems to be no end to this insatiable hunger for mining anything and everything without considering alternative sustainable utilisation of resources that lie above the land which everyone wants to upturn and destroy to get to the minerals below. The forests are degrading; impoverished and displaced people have no choice but to depend on these fast-depleting forests, which degrade them further. All large mammals and predators except elephants are gone, whatever medium-sized and smaller wildlife survives is hunted down, elephant-human conflict is at an all-time high as bewildered herds move unpredictably with their historic forest corridors gone, and above all, the sheer level of administrative apathy towards all this can sink the hearts of even the most optimistic people. The only possibility of revival lies if conservationists and social scientists, upright officers and villagers, can come together and set our differences aside to face the common adversaries that seek to destroy the world of both humans and wildlife.

S.E.H. Kazmi: The “Hazaribagh ecosystem” is over. There is no hope. You will see the worst consequences of “development”. Coal mining and linear developmental projects have severely affected the connectivity. There is a mad rush for acquiring coal and other minerals and of roads and railway lines to transport the minerals. The development lobby can bulldoze or buy all the law enforcement agencies. There is not much hope.

The Forest Rights Act, 2006 has supporters and detractors, but what is your take on the grant of individual rights as against community rights?

Raza: I think the main reason behind the contestations over FRA is something very basic – the law has rarely been implemented in letter and spirit, and this works both ways. There are plenty of cases where genuine rights have not been settled and there are cases where there have been encroachments under the misguided notion that clearing a patch of forest and cultivating on it will automatically result in the grant of a patta. The former of the two failures makes rights activists suspicious of conservationists and Forest Departments across India, the latter failure makes many conservationists blame FRA for forest loss. However, I personally feel that the law in itself can be an incredible aid to conservation if only the two sides could come together and ensure that the law is implemented, both vis a vis individual rights and community rights, honestly. If we started using FRA and conservation legislation such as the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 and Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 to complement each other in the bigger fight against the destructive projects, it could be a game-changer in conservation efforts in India. However, for that, both sides of the divide will have to shun their ideological dogmas and try learning about each other. I find many rights activists often woefully ignorant of even the basics of wildlife ecology and many conservationists clueless about socio-cultural aspects of communities that live in or are dependent on our forests. We need to change this tendency to work in silos and often against each other rather than the common adversaries that seek to destroy the lands that sustain both wildlife and forest dwellers.

S.E.H. Kazmi: I will prefer to follow both laws in letter and spirit. Unfortunately, both sides treat each other as enemies. It is time to sit together, reconcile our differences and hold each other’s hands and confront the “wrong notions” of development. I do wish and hope that the younger generation will put their improved communication skills to use, and do better than our generation.

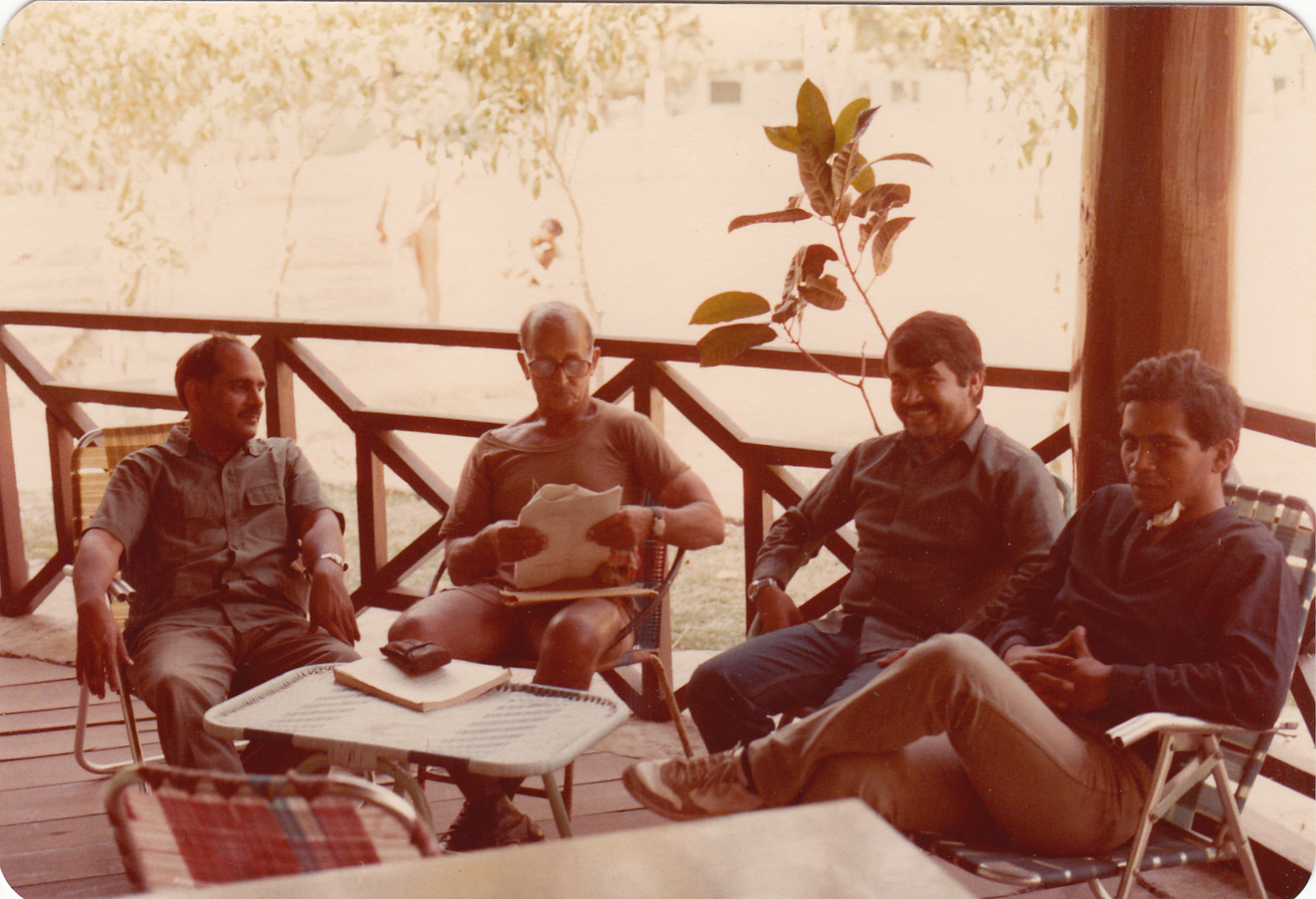

(Left to right) Vijay Singh (retired forester), S.E.H. Kazmi, Shyam Vyas Rai (retired forester) and Mr. Haq, Range Forest Officer (Chhipadohar) in the verandah of the Mundu Forest Rest House – one of the Kazmi family’s favourite haunts – in 2009. The Mundu Forest Rest House was blown up by maoists on January 30, 2006, after security forces began using the Forest Rest House as a camping ground during anti-naxal operations. Photo: Raza Kazmi.

In light of the Dasgupta Review and IPBES are you hopeful that policy makers will wake to the fact that the economy is wholly dependent on natural ecosystems and that a U-turn might be on the horizon?

Raza: I might sound cynical, but I am not very hopeful. At least not right now. In our country, all studies and recommendations usually come to naught if the politicians calling the shots are ecologically illiterate. Our legislators need to be given mandatory ecological education, and perhaps some novel schemes can be tried out where politicians must adopt a forest or a PA in their constituency on the lines of the Prime Minister’s ‘Adopt a Village’ scheme. Under such a scheme, they can be mandated to not only undertake a certain number of field visits to forests and PAs in their constituency but also make presentations on their learnings and vision for their constituency’s forests at the end of every session in their respective legislatures.

S.E.H. Kazmi: The policy makers toe the line of their political masters. They will ignore all such reports. I do not see any turn but a straight road to abyss.

Are young people today aware of the connections between coal mining, ecosystem destruction and climate change?

Raza: Yes. I can’t remember as much public engagement, especially from youngsters, over issues of mining, ecosystem destruction, and climate change at any other point of time in history. Even a decade ago, when I first started writing, I would have never imagined as many people engaging on these issues as they do today. So that gives me hope. But we need to harness this potential and convert it into substantive action. Perhaps we could take lessons from grassroots movements like Chipko Andolan or the more recent Niyamgiri movement by the Dongria Kondh adivasis.

S.E.H. Kazmi: Yes they are but their number is few in comparison to those who want to make a fast buck at the cost of environmental destruction.

If you had a magic wand what three wishes would you give the planet.

Raza: Aah, well that is a tough one, but let me give it a go:

1. Every child gets some days every year to just sit by a gurgling river, marvel at a beautiful bird fritter around in trees, watch a colourful butterfly sit on a flower, gaze at a deer quietly grazing about, get to see a pugmark of a tiger on the forest floor, observe an elephant family, experience the morning mist wafting over a forest canopy, breathe in and play around in the rejuvenating air of a forest, smell that distinct ‘jungle ki khushbu’ as I call it, and see a clear night sky twinkling with a million stars.

2. Local communities who sacrifice the most for conservation become not just the first but prime beneficiaries of all economic, ecological, and social benefits that accrue out of a wildlife-rich, healthy and biodiverse ecosystem.

3. Kindness, compassion, and tolerance, towards each other, for our flora and fauna and all those places where they dwell.

S.E.H. Kazmi: It’s truly wishful thinking but I would use the wand to ensure:

1. Zero population growth of Homo sapiens sapiens.

2. Zero corruption.

3. 100 per cent environmentally-sensitive egalitarian society.