Meet Marilyn Hoyt And Dan Wharton

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 8,

August 2022

By Bittu Sahgal

I first met Marilyn Hoyt and Dan Wharton way back in 1986 when my wife Madhu and I were delegates at the first International Snow Leopard Conference held in Srinagar, J&K, India. Both professional, both warm and extremely personable. The four of us had no idea how that single four-day wildlife meeting would set up a lifetime’s friendship involving all our children. The late Dr. Helen Freeman, Founder of the Snow Leopard Trust, had organised the conference, with the help of the late Chief Wildlife Warden, Mir Inayatullah and the very first book on the snow leopard was designed and printed by Sanctuary Asia, under the eagle eye of the inimitable Dr. Freeman.

We all met again in July 2022 in Toronto, where I had come to discuss partnerships for a solar festival in Mumbai in the first quarter of 2023. What follows turned out to be a fill-in-blanks session for us, where we got to know them even better than we thought we did.

Marilyn and Dan, tell us about your childhood. Your families?

Marilyn: My parent’s world was shaped by two signature events: World War II and the Great Depression. The value placed on hard work and the sense of great potential coming out of these events informed everything about my upbringing.

I was born in Camas, Washington, home to the world’s largest diversified paper mill and where my father was part of a small group of chemists who founded the Chemical Research and Products Division. Gestated and born in the sulfur air, growing up in a polluted town, left me with lifelong asthma and an immunity disorder. We lived in a home near forests and a lake outside town and my grandparents, too, lived near a stream in the woods. So, nature was a large part of my childhood…

By the time I was 16, federal clean air and water regulations reduced the paper mill’s air and water pollution. My father secured more patents than any other chemist in the company… particularly in the use of waste products from paper manufacturing for the growing field of oil drilling. In his lab, the long steel counters covered with test tubes and equipment that used to tease apart the components of trees were also a part of my informal education about the complexity of the natural world.

Meanwhile, my mother raised my younger brother and me, canned and froze vegetables and fruit from the large garden we kept, and volunteered at local schools, our church, and various women’s organisations. My parents were mightily committed to providing us with education, the arts, religious and character-building activities. We were expected to excel in schoolwork and activities, do home chores, and spend time with our grandparents, family and friends. We both had jobs… me as a babysitter and berry picker, and later in a drug store and department store. Vacation camping, hiking, and night canoeing after work defined the natural world as a source of beauty and respite. My undergraduate college years were in a city surrounded by gorgeous rocky prairies, and hikes in piney mountains or wildflower outcrops competed with final exams every year.

Graduate school in Cleveland, Ohio was counterpoint to these early years. In the early 1970s, it featured a river and the Great Lake shoreline that periodically caught fire and pristine snowfall was tinged with black, two days after it fell. It was my first encounter with unchecked industrial pollution and coal-dominated energy resources.

Dan was the chairman of the Snow Leopard and Western Lowland Gorilla programmes at the Bronx Zoo, New York, and also of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). He was particularly interested in the application of population biology to the small populations of threatened and endangered species in zoos that would dwindle away if not scientifically managed. Photo: Thomas Rajan.

Dan: I was born a third-generation Oregonian, descended from great-grandparents who migrated to the western United States from New York, Virginia, North Carolina and Missouri. My childhood was wonderful, guided by parents who appreciated my intense interest in animals, nature and science. That said, I couldn’t wait to grow up and get on with being much more involved in the things I loved. My maternal grandparents were also very much a part of my life; my grandfather and I always planning various domestic animal projects whenever we were together. The whole family was close to the land, being farmers and commercial beekeepers. Honeybee colonies might be the best childhood laboratory there is, and I was very much engaged with the biology of the bees, even if somewhat less interested in the business side. My father, both of my grandfathers and several of my uncles were commercial beekeepers with literally thousands of honeybee colonies managed across several states. My brother and I had almost 50 first cousins, many of whom became life-long friends.

How did you lovely people meet?

Dan: We met through a mutual friend, one of my fellow Peace Corps volunteers in Ecuador who was a Whitworth College classmate of Marilyn’s. After Peace Corps, those of us living in the western states decided to have a “camping reunion” on the Clearwater river near Kooskia, Idaho. Marilyn came along with our mutual friend and invited me to come work in Olympia, Washington while I was planning to go to graduate school in Vermont to prepare for an international career in endangered species management. And I did, helping pay rent with Marilyn who was running education and grant programmes for the State Arts Commission and her roommate. After I left for Vermont, we had a robust correspondence and when next we got together, a year after we met, we decided to get married right away in my grandparents’ house in Harper, Oregon.

What led you to choose the careers that drove you to the top of your professions?

Marilyn: During my college years, and graduate work in a conservatory, I realised that I enjoyed the management side of the arts much more than the performance side. I continued work with the Washington State Arts Commission until we relocated to New York when Danny moved into management and conservation science at the Bronx Zoo.

In New York, there were so many opportunities… first a national job in arts in education, then a return to arts grantmaking with the nation’s largest community arts council grants programme, and then the opportunity to lead fundraising for the establishment of New York’s first science and technology museum.

At the New York Hall of Science, I was introduced to the National Council of Science Museums in India with its rapidly growing system of science centres in large and small cities. We were the first in the new world to replicate their initiative in building science playgrounds to teach the fundamental principles of physics and engineering.

National and international consulting, leadership in nonprofit professional societies, conference presentations and professional writing were sidebars to these positions. Even in retirement, the rich web of professional contacts continues.

We also raised three daughters and a son, all with robust careers, and invested in their own families and friends. One son-in-law is engaged in conserving nearly 2,000 acres of marshland in southern New Jersey, so we have a chance to continue following the evolution of conservation policy. And, as always, nature is a source of respite, interesting informal discovery and beauty. At the same time, we support nonprofit organisations engaged in conservation and science education.

Dan: I always knew I wanted to work with animals. A television show featuring San Diego Zoo curators really set the wheels in motion, even though I was only six years old. Peace Corps and time in Ecuador led me to apply to a master’s programme in International Administration where I emphasised international conservation and the emerging new role of zoos in wildlife conservation. After Marilyn and I were married, I interned at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington where I gained experience in the workings of animal care and zoo programme administration. I was fortunate during this time to win a one-year Fulbright Scholarship to Germany with the objective of studying zoology and working as an intern in the Allwetter Zoo in Munster. After Germany, I began my career at the Bronx Zoo and the New York Zoological Society (later renamed the Wildlife Conservation Society), pursuing a Ph.D. in Biology at Fordham University at the same time.

Marilyn as research assistant in Santiago, Galapagos in 2008. Over the course of her illustrious, decades-long career, she has had the opportunity to work on education, grantmaking and fundraising in the arts and sciences. She has also been involved in national and international consulting, leadership in nonprofit professional societies, conference presentations and professional writing. Photo Courtesy: Dan Wharton.

What did science, a part of both your lives, do for you and what do you think you did for science?

Marilyn: My grandparents and great grandparents homesteaded, so my childhood was full of stories of their making farms in wild lands. The natural world was embedded in our lives. The competition between forest, water and fish preservation and their harvest to increase prosperity were constants. I think the best introduction to science is the informal learning that comes with growing food, observing bugs and mushrooms and fish in the wild. The occasional chemistry set with its growing crystals and stained fingers is a worthy adjunct.

My parents were both chemists. The material world was accessed and understood via the language of science in my home. Habits of asking questions, forming a theoretical answer, and then testing its veracity continue to inform my adult life. Married to a scientist and later working with scientists in a museum, I have had opportunities to encourage research on how the public engages with science and technology.

Dan: I loved the mind-set that you need to develop to understand the line between what you know and what you don’t and how assumptions are just that until they are tested scientifically. Animal care, especially that which has a conservation impact, requires a lot of questions and some reasonable answers. I enjoyed being both driver and consumer of science for animal care success and its conservation outcomes. There was an interesting and stimulating cohort of zoo scientists I had the pleasure of working with in the early days. We were primarily focused on the application of population biology to the small populations of threatened and endangered species in zoos that would dwindle away if not scientifically managed. I became the chairman of the Snow Leopard and Western Lowland Gorilla programmes. As Executive Editor of the zoo profession’s peer-reviewed science journal Zoo Biology, I had a birds-eye view of the scientific work taking place in zoos for over 12 years.

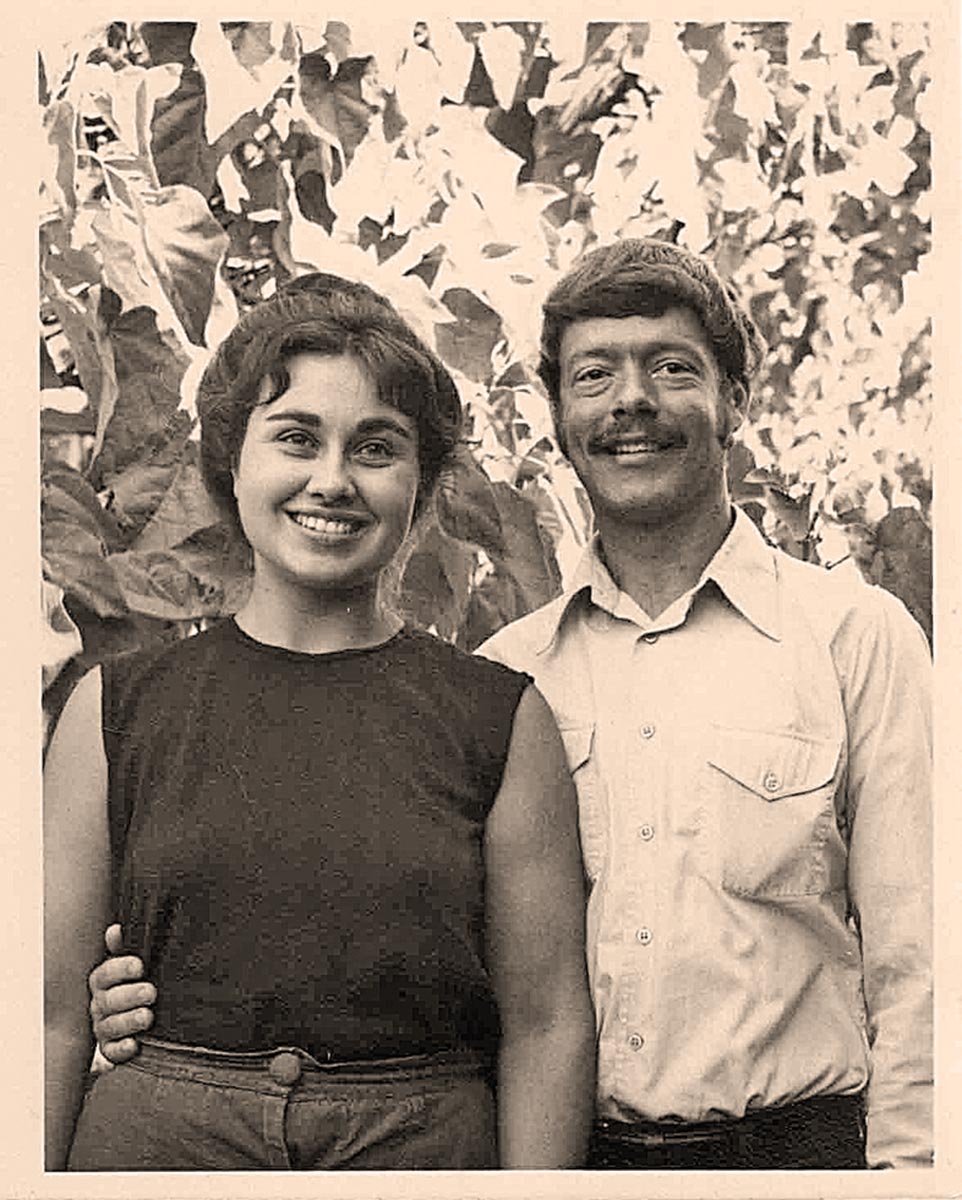

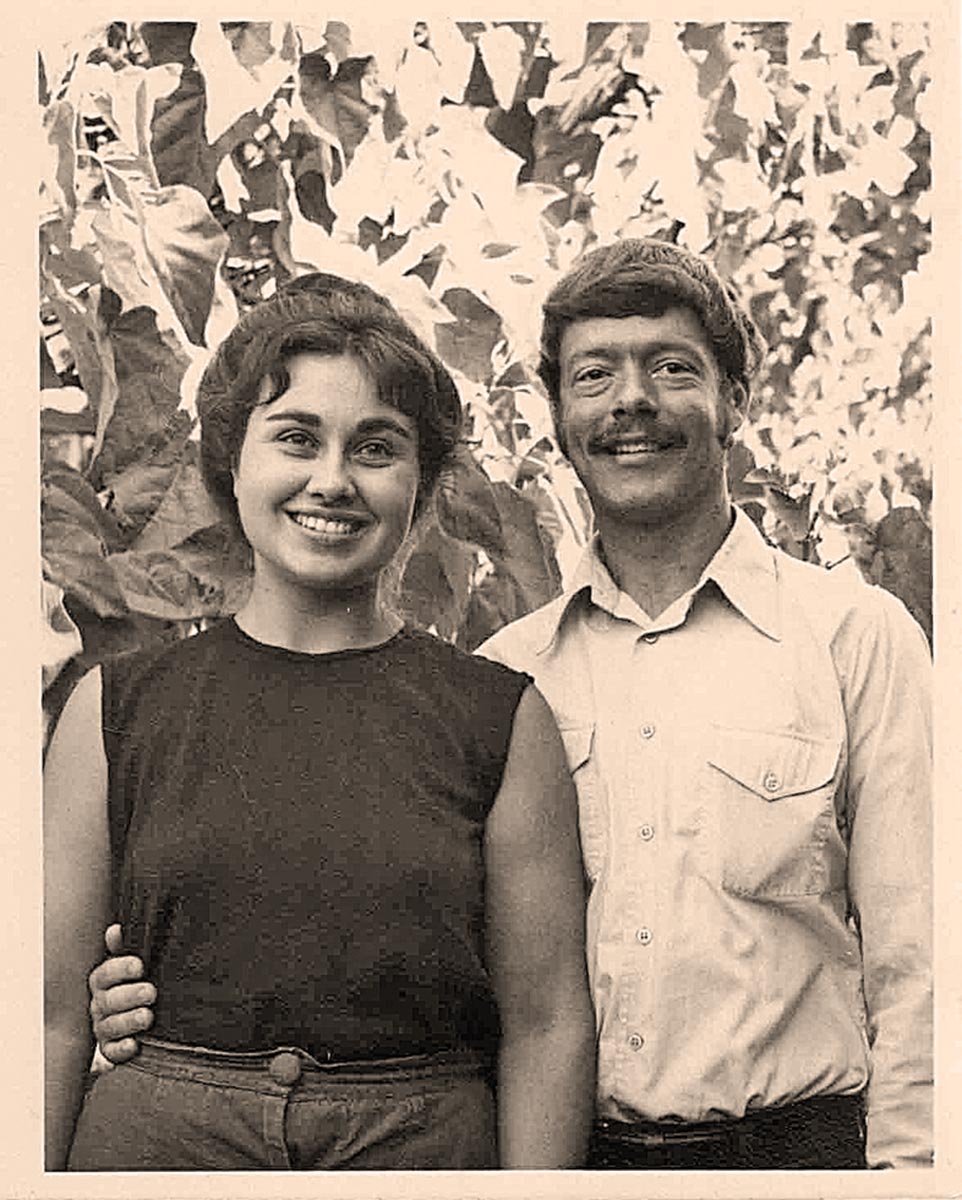

Dan Wharton and Marilyn Hoyt in Tanzania in 1986. Successful in their respective careers, the duo have also enjoyed travelling across the world – including India, which they first visited in 1986 to attend the first Snow Leopard Conservation Conference. Nature, says Marilyn, has been a constant source of respite, interesting informal discovery and beauty. Photo Courtesy: Dan Wharton.

India has been a part of both your lives in more ways than one. Your take on India today?

Marilyn: We are now entering our fourth decade of engagement with India. One lifetime is not enough time to truly know and understand this amazing country and its extraordinary history and culture. My knowledge of India is like slices of a very rich cake: conservation of the natural world and the communities that depend upon it; the launching of the first cell tower networks opening remote communities to ideas, markets and opportunities never before accessible; and the growing network of science centres and a youth organisation increasing the public understanding and engagement with science, science education and informed environmental action. Through personal relationships, conferences and professional education, I have had opportunities to engage with and learn from these activities in India.

Dan: My window on India is narrow and largely sentimental and so I can’t speak with great authority. To me, India is a country of the “big tent,” a place where people find foreigners as they are, something that seems rare among nations. Certainly, India’s history has been one of many peoples coming together, often clashing or disagreeing, and yet a large quotient of mutual understanding happening at the same time. This is remarkable. We all know how the British Empire changed the world but in a narrow on-British-terms kind of way. I like to think that the Indian diaspora will also change the world but in a smarter, kinder and much more poetic fashion, perhaps the realisation of Gandhi’s good idea about Western civilisation.

Dan Wharton in Galapagos in 2008, for research on Nesoryzomys swarthi, an endemic species of rodent from the island. From a young age, he found fulfilment in studying animals and the natural world and felt like the best use of his enthusiasm would be to learn as much as he could and try to make a difference in the field of wildlife conservation. Photo Courtesy: Dan Wharton.

You visited India for the first Snow Leopard Conference. What memories and associations have stayed with you?

Marilyn: No one ever forgets their first encounter with India. Talk about drinking from a fire hose... especially when the first contact is in the political complexity, beauty and challenges of Kashmir.

The 1986 Snow Leopard Conference brought together senior officials, field biologists, zoo professionals and conservationists responsible for conserving and propagating snow leopards. This was a first in the world… professionals from diverse fields meeting to address snow leopard conservation. Many of those at the conference had never seen a snow leopard in the wild. The role of snow leopards as an apex species whose population health reflects that of every other species in their range (including humans!) fascinated me. Following this conference, efforts to camera trap and inform both local populations and conservation officials about the species were expanded. Local communities in snow leopard ranges have formally undertaken protection initiatives. In Mongolia, for instance, national law gives villagers authority to protect the species… including a say on mining permits. Public monies are available for herders who lose stock to predation. Discussions of cross-border protection efforts were also undertaken at the conference and now, formal and informal cross-border corridors protecting its migration are in place.

Dan: New friends and colleagues were discovered that have enriched both our personal and professional lives. And then there was India itself, so beautiful, so unique and unforgettable, and a country I would return to again and again. The Conference itself was an experiment in bolstering local conservationists’ work and calling attention to the snow leopard as a national wildlife treasure. The evidence that it was successful in its objectives gave rise to more conferences in other countries, namely China and Kazakhstan. This many years later, it is gratifying to see that snow leopard numbers in India are holding, perhaps increasing, an outcome we all wished for.

You have both been recognised and awarded several honours. What have these meant to you?

Marilyn: Now that I am older and retired, what I enjoy most about the honours I’ve received is the degree to which they remind me of the many opportunities I have enjoyed across many fields of endeavour… from scholastic honours in state music and science as a young student and winning a Metropolitan Opera Audition, to professional recognitions in grantmaking and fundraising and those wonderful little hand-painted clay tablets gifted by my children for Mother’s Day.

Though I treasure the many honours related to being a “first woman” or “leading woman”, I yearn for a period when being an “accomplished woman” in any field is not particularly noteworthy because it is so very common.

More than the awards and certificates, I have valued the honour that attends being invited to join or head significant committees… to consult… to present at conferences… to write for professional publications and to teach. Towards the end of my career, I most particularly enjoyed teaching in the National Council of Science Museums summer professional workshop and a (U.S.) National Science Foundation-sponsored advancement course for biologists and environmental professionals. Working with wonderful colleagues to advance the field is the highest honour.

All of these represent the richness of a period in history when education, professional advancement and travel became more accessible. And all of these represent investments made in me as much as investments I have made.

Dan: Any honours along the way have been much appreciated but were never the point. I was blessed at any early age to find meaning in studying animals and the natural world. It seemed like the right thing to use this enthusiasm to see if I could learn as much as I could and try to make a difference, to help zoological gardens take a bigger role in wildlife conservation. I would do all of it again.

As Executive Editor of the peer-reviewed science journal Zoo Biology, Dan had a bird’s-eye view of the scientific work in zoos.

What do you make of the state of our biosphere today?

Marilyn: Our planet is in trouble. There is no doubt about it. And some of the advances we have made in regulating for clean water, clean air, ozone and other pollutant reductions are being rolled back even as others move ahead. That said, populations worldwide are much more aware of the dangers to themselves and their homelands from environmental degradation. And they are increasingly demanding change. As a result, there may be more potential for resolution than there has ever been.

Dan: It is somewhat axiomatic that to be a conservationist, one must be an optimist. Yes, the beauty of an intact nature is under intense threat and over the last 50 years, there has been a steady erosion of habitats, wildlife populations and even whole species. But some things are better, primary among them is the human awareness of nature and its vital importance to the planet and human existence. That is not enough, of course, so the trick is to turn this positive awareness into unbreakable political will to protect what we have left, expand it and make it thrive.

What dominates your life... hope or despair? Is the Anthropocene going to be the undoing of Homo sapiens?

Marilyn: For all the current and looming disasters, this period in history has accomplished so much. A smaller percentage of our global population is at war, enslaved, malnourished, or dying at birth or at an early age than ever in the history of mankind. Because we can see further than the “man with a hoe” who has dominated the millennia of our existence, our obligation to press for the health of ourselves and our planet is greater.

And whether in the end, we destroy ourselves and our planet, or win a healthier, more whole existence hangs in the balance during the current century or two. On any issue there can be cause for despair… but there is no reason whatsoever to drop the tools of sincere dedication, science and technology and the culture that encourages search for ever better ways to develop each of our talents and unite our efforts for the common good.

Dan: There are two ways to look at this. Will humans and their domination of the earth eventually lead to literal human extinction, or will it just be the end of the Anthropocene? Like all successful species that have managed to attain worldwide distribution, humans are unlikely to disappear entirely anytime soon; however, there are many scenarios in which a breakdown of modern systems might set us back to some other age. However, I see tools emerging that might be the key to human salvation on both fronts. It all boils down to whether, or not, we can use these tools to make truth dominate human discourse. Virtually all the human-made problems in this world are traceable to lies by those who have too much to gain by selling those lies.

Dan Wharton and Marilyn Hoyt and Madhu and Bittu Sahgal in Toronto, 2022. The four first met in 1986 as delegates at the first International Snow Leopard Conference in Srinagar, J&K, India. That single, four-day wildlife meeting has expanded into a lifetime’s friendship. Photo Courtesy: Bittu Sahgal.

If you had a magic wand, what three wishes would you ask for the planet?

Marilyn: “Get crackin’ capitalists! Our wealth model built on increased consumption by increased population is coming to an end. What’s our next engine to drive prosperity?”

“Hang on, plankton! We are abusing you mightily but since you are the source of most of the oxygen we breathe, we need you to prosper. We are so hopeful that you are persistent while we think of how to get our act together on global warming.”

“Get a grip, people! When we get anxious, we tend to turn on each other. This is no way forward. Every little bit of uniting on any topic whatsoever increases our capacity to ultimately save the planet.”

Dan: That truth will dominate human discourse; that human commerce will heavily support nature conservation in recognition that most of the blueprints for human commerce came from nature, and that the peace sciences will have budgets larger than all the military budgets.

Dan and Marilyn in 1973 after their engagement. Then as now, the couple believe that there is cause for hope and encourage young people to find a place where their voice and talents can make a difference. Photo Courtesy: Dan Wharton.

What would your one message to youth be today?

Marilyn: Join the work of the world! Find the place where your talents can make a difference and press forward. Your life must count for something or the suffering you are bound to endure at times makes no sense. And even as you move ahead, become knowledgeable about what came before… it’ll save you the trouble of repeating things that don’t work and set you in the great arc of history.

Engage with science to understand the material world. It leads to true understanding of our existence and the fundamentals of what is happening to us and how we can change it for the better.

Engage with your culture to understand the world beyond the material. This effort can lead to wisdom, or some approximation of it. Ground yourself in some... whether it’s “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” or “Transcend the bullshit.”

Dan: Remember that there is no mystery to what humanity needs to do to restore a healthy planet. The scientists and the educators have done their jobs well, yet progress is slow, often non-existent. As you enter the adult world, ask why and seek the truth. Put your voices and talents together, invent new tools for honest discourse and insist that the leaders of state and industry work for the planet and not against it.