Meet Anwaruddin Choudhury

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 12,

December 2021

In conservation circles, Anwaruddin Choudhury is a well-known name, with a resume that includes Divisional Commissioner of Barak valley, Development Commissioner for Hill Areas, Deputy Commissioner of Baksa and Lakhimpur districts in Assam and Commissioner and Secretary to the Government of Assam. Ornithologist, mammalogist, wildlife photographer, artist and author, his efforts saw the establishment of 13 sanctuaries and two elephant reserves in the Northeast, the notification of Dibru-Saikhowa as a national park, and the addition of Laokhowa and Burhachapori Sanctuaries to the Kaziranga Tiger Reserve. He also pushed to get the White-winged Wood Duck declared as a state bird of Assam. This guardian of India’s Northeast is now working on protecting two roosting sites of the Amur Falcon in Assam. Bittu Sahgal, uncovers the many layers of this year’s Sanctuary Lifetime Service Award 2021 winner.

Anwar, many of us know of your incredible, lifelong work but very few really know about your childhood!

No one has actually asked me this before Bittu! I was born and brought up in Shillong, then the capital of Assam, now of Meghalaya. My parents (Alauddin Choudhury and Hena Mazumder) were not naturalists or environmentalists, but they were extremely supportive of whatever I did during their lifetime. Back in those days shikar was as normal as going out on a jungle drive today is for many. My grandfathers and an uncle whose daughter was later to be my wife, were all fond of hunting and I once accompanied my uncle on his jungle jaunts way back in 1967. My maternal grandfather was Abdul Matlib Mazumdar, a Gandhian and freedom fighter. He was also a cabinet minister in undivided Assam between 1946 and 1970 and hence, he too was a hunter whose favourite haunts were what are now the buffer forests of Manas, and the Garo Hills and the wildlife-rich Barak valley.

So, who influenced your passion to protect wildlife?

I had no specific influencers as regard my passion and commitment to wildlife protection. Since my childhood, the forest and its denizens were my greatest influencers. But, yes, my parents and grandparents shaped me into the human being I am. My wife (Bilkis Begum Mazumder) and children (Zebian Farhin and Farhan Anwar) influenced me too. They supported my passion and allowed me the luxury of time away from them to be with, study and protect wild nature.

Anwaruddin (extreme right) with his parents in the early 1960s at Shillong. He was born and brought up in this hill station – then the capital of Assam, and now of Meghalaya.

And the transition from a childhood love to one of India’s finest, green-hearted scientists and administrators…

My childhood metamorphosed into scientific observations while I was still in school! At first it was the Children’s Encyclopedia of Knowledge: Book of Wild Life by Collins. And later E.P. Gee’s iconic book, The Wild Life of India, Das and Mookerji’s Textbook of Biology, and, of course, Sálim Ali and Laeeq Futehally’s Common Birds of India. It was an unplanned journey. The occasional wildlife issues of The Illustrated Weekly of India, piqued my interest. But it was only when I did my Masters in Geography that I came to understand maps, habitats, and wildlife distribution. Almost inevitably, wildlife study and identification of potential Protected Areas soon became an obsession of sorts.

Yet you chose to be a Civil Servant! Why did a dyed-in-the-wool wildlife man become a bureaucrat?

You must remember that back then wildlife protection was not a career option. I thank my stars I applied for, and was selected by, the Assam Civil Service (later on inducted into the Indian Administrative Service). Every single distant posting fed my insatiable research interests and conservation passion. Wherever I travelled, my cameras and journals would be the first to be packed. I was truly lucky. My job involved meeting diverse people living close to the land. Coming to grips with their problems, I learned more about human-nature relationships than any institute could possibly teach. Sometimes this helped me to enforce the law in the field, other times to create and implement policies that reduced negative human-animal interactions. This even during postings that involved me sitting in the Secretariat Office. But my greatest fortune was becoming a part of the Assam Forest Department. A very welcome life-opportunity for me.

You have certainly travelled more than most!

Yes, but I repeat, I could have done nothing if not for the family support I received and the long absences for which they would forgive me.

Anwaruddin with his wife Bilkis Begum Mazumder and children, Zebian Farhin and Farhan Anwar, in front of Salim Chishti’s tomb in Fatehpur Sikri, 2009.

Photo Courtesy:Anwaruddin Choudhury

Switching tracks… it’s been a quarter century since you joined the Rhino Foundation. What was that experience like? What kind of support did you get?

Yes, I was the founder Chief Executive, but the real hero was the legendary Mrs. Anne Wright. Some tea companies, notably the Tata Tea Company, headed by R.K. Krishna Kumar truly enabled me to do whatever it was I managed to do. When I ended my deputation, I continued as Honorary Chief Executive, a post I hold to date, with the intervention of Ranjit Barthakur, now of the Balipara Foundation.

Deputation? As a government servant you were allowed to join an NGO? That must have been rare?

That is putting it mildly. It was a path-breaking event in Assam. The very first time a Government to NGO deputation was formalised. This was thanks to Hiteswar Saikia, then the Chief Minister of Assam and Jatin Hazarika, bureaucrat-turned adviser to the Chief Minister.

Returning to your NGO experience? How did that go?

Very well I would say! The Rhino Foundation’s first project was support to patrolling staff, at a time when the Assam Government was in the grip of a severe financial crunch. Almost instantly, our patrolling was strengthened. And this was a huge boost for staff morale. We cannot take direct credit for it, but the renewed vigour of our field staff had a direct impact on reduced poaching incidents.

Who else helped?

Almost everyone. The marked improvement in relationships between Assam’s NGOs and the state government was palpable. In 1996, Dave Fergusson, Regional Head, US Fish & Wildlife Service, visited Assam on invitation from the Rhino Foundation. I arranged a meeting between him and the late Nagen Sharma, the wildlife-loving Forest Minister of Assam. This resulted in several local NGOs getting much needed direct support. This was also when an Assam Forest Department-sponsored NGO called Wildlife Areas Development and Welfare Trust was formed, which received considerable funding from the US Fish & Wildlife Service for their field projects. I have to say that however I wished more tea companies had the vision to support biodiversity protection.

With noted conservationists, Mrs. Anne Wright, late William Oliver and Bittu Sahgal at Guwahati in 2013.

Photo Courtesy:Anwaruddin Choudhury

What is it about the natural world that inspires and motivates you to fight on in the face of so many obstacles?

Yes, and the obstacles only seem to grow! People do not realise that it is not wildlife that need our support, it is we who need help from wild species for the survival of humankind. As you can imagine, it has not always been smooth going. At various stages we felt that all we were managing to do is delay the inevitable extirpation of our wilds. But somewhere within the core of those working with nature, is the knowledge that nature manages to survive and begins to repair itself, almost the moment we stop harming it. Working with communities I have witnessed many success stories. Also, we managed to divert roads and powerlines, using administrative powers. I am inspired by challenges, motivated by successes and perhaps even more by failures, which kickstart determination to protect what I love even more.

What is your take on the large dams being built in the Eastern Himalaya and what impact might climate change have on the projects?

Although I was a part of the government, I always expressed independent views, because I could see the extremely poor quality of EIA reports and a tendency of power companies to suppress the truth. Governments do not want their policies to be criticised by its officials, but it never stipulates that views should not be expressed if an officer sees something that could harm the public. Such harm is exemplified by the submission of poor EIA documents.

I know what you mean. I have seen my share of shoddy EIAs. As a member of the MoEF’s Infrastructure Expert Advisory Committee, the late Shyam Chainani of BEAG and I, incurred the wrath of a Minister looking to give a clean chit to an obviously doctored EIA document. It was in the early 1990s and when we were requested to take back our dissent, we refused, saying the EIA belonged in the fiction section of the MoEF’s library. The Minister quickly ‘reconstituted’ the Expert Committee without us being appointed! The project eventually proved to be an embarrassment and a financial and ecological disaster.

As you know, I have examined and commented on several EIAs. Virtually all were of very poor quality. I am not against power projects, but feel that we need quality not quantity. India’s hydro-electric projects generally operate at around half their installed capacity. Better efficiency, and strict monitoring of conditions, including the protection of catchment areas, would dramatically improve efficiency. Besides, small and medium dams are far better options to mega dams that submerge large, biodiverse valley forests, thus destroying the very biodiversity we know to be critical to moderating our climate. What is more, the downstream impacts on livelihoods and the natural habitats of riverine ecosystems are severe. A good EIA would diagnose problems to the advantage of the project promoters too, but so long as short-term objectives rule the day, ‘manufactured’ EIAs will be the norm. I know of decade-old unsettled compensation cases across the country.

Anwaruddin Choudhury in north Bengal, 1995. He thanks his stars that he applied for, and was selected by, the Assam Civil Service. Every single distant posting fed his insatiable research interests and passion for conservation. Wherever he travelled, his cameras and journals would be the first to be packed.

Photo Courtesy:Anwaruddin Choudhury

And then we have the issue of climate change!

The impact on climate change is palpable. Other ill-effects include carbon dioxide and methane emissions from tropical reservoirs. The recent COP26 meet underscored all these issues, stating unequivocally that natural ecosystem regeneration is vital to any hope we have of meeting the imperative of limiting global temperatures to a maximum level of 1.5 0C. As an administrator and a scientist, I know this is possible if we work in tandem with nature’s imperatives.

Talking about science, what is your take on the Bombay Natural History Society?

It is a venerable organisation with a critical role to play in India’s biodiversity recovery. I had only heard of the BNHS through its Journal, and the many lists and references and bibliographies I would refer to in the 1970s. It was back in 1981, that I first wrote to them, asking to become a member. Subsequently I began writing for the journal, my first article appearing in 1988. My list of published articles and papers now totals 85, with 10 more under review, or editing. My initial correspondence was with the late J.C. Daniel.

When Asad Rahmani took over as Director he extended BNHS’s activities to the Northeast in the true sense of the term. From that time, I started visiting BNHS frequently. The Director’s residence became my temporary camp on several occasions, especially when we were identifying sites and preparing to list India’s Important Bird Areas, or IBAs.

Anwaruddin Choudhury’s pioneering studies on the White-winged Wood Duck played a huge role in it being declared the state bird of Assam in 2003. This Endangered species resides in dense tropical evergreen forests.

Photo:Soham Das

You should visit and work more closely with the BNHS again.

I would like to. Asad Rahmani will confirm that virtually all the site accounts from the northeastern states were authored by me (in both the editions) with inputs from several other participants. Many sites had to be bifurcated or created at the last moment. For instance, the same site was somehow listed twice in the first edition’s proof as “Magu-Thingbu” and again as “Thingbu-Magu”. So, one site had to be changed keeping the IBA number intact and the alphabet “T” as well. After scratching my head while searching for a solution I coined a name “The chapories of the Lohit River” and wrote the site account. My library and files are enriched by photostat copies of old and rare books from the library of BNHS and I also worked at the museum.

You ended up describing three new species of giant flying squirrels, plus a subspecies of a hoolock gibbon. What went through your mind when your discoveries were confirmed?

My first description was six years after I first examined the specimen. I did not rush. I confirmed and reconfirmed my findings several times, visiting museums across the world including the Smithsonian, American Museum of Natural History, the Field Museum of Natural History, the Berkeley University Museum, the British Museum and our own Zoological Survey of India, ZSI. That time-gap wore me down but I gained much experience on flying squirrels that evolved differently because of river barriers.The hoolock subspecies I surmised was way back in 1989. Looking across the banks of the five to seven kilometre wide Lohit river, I thought to myself that if such a river created a barrier for squirrels, perhaps even hoolock gibbons living on opposite banks should be affected by the same barrier. I began to explore differences between hoolocks on either side of their watery divide. “They must be slightly different,” I said to myself. Ultimately, I could confirm my postulation in 2013 when severe habitat loss in Arunachal Pradesh’s plains area permitted me to more easily observe the hoolocks. A conservation breeding facility was established at the Itanagar zoo. Two of the flying squirrels and the hoolock were also assessed by the IUCN Redlist.

More than jubilation, I felt a sense of relief from the tiresome work that consumed years of my life!

There must be so many other species awaiting reclassification.

Well, I thought the Arunachal macaque, which I first sighted and photographed in 1997, was a subspecies of the Tibetan macaque. I now believe it was a subspecies of Assamese macaque. A full eight years later it was described as a species in 2005 by other authorities.

Tell me about Karbi Anglong. Have we lost this crucial NE battle?

No, I still have hope. But I am disappointed that the Protected Areas we had notified after being identified by me, with help from Jotson Bey, then Chief of the Autonomous Council in 1990s, are not being adequately managed. Bey was a nature-lover and said he was motivated by my book A Naturalist in Karbi Anglong. After inviting me to his home, and after much discussion, he gave the nod to the proposals made by me in the book. But sadly, Karbi Anglong’s forests are being lost to encroachment and rampant tree-felling in some areas. But our battle is by no means lost. We still have a chance to regenerate this biodiverse wonderland that is part of the culture of the Karbi people.

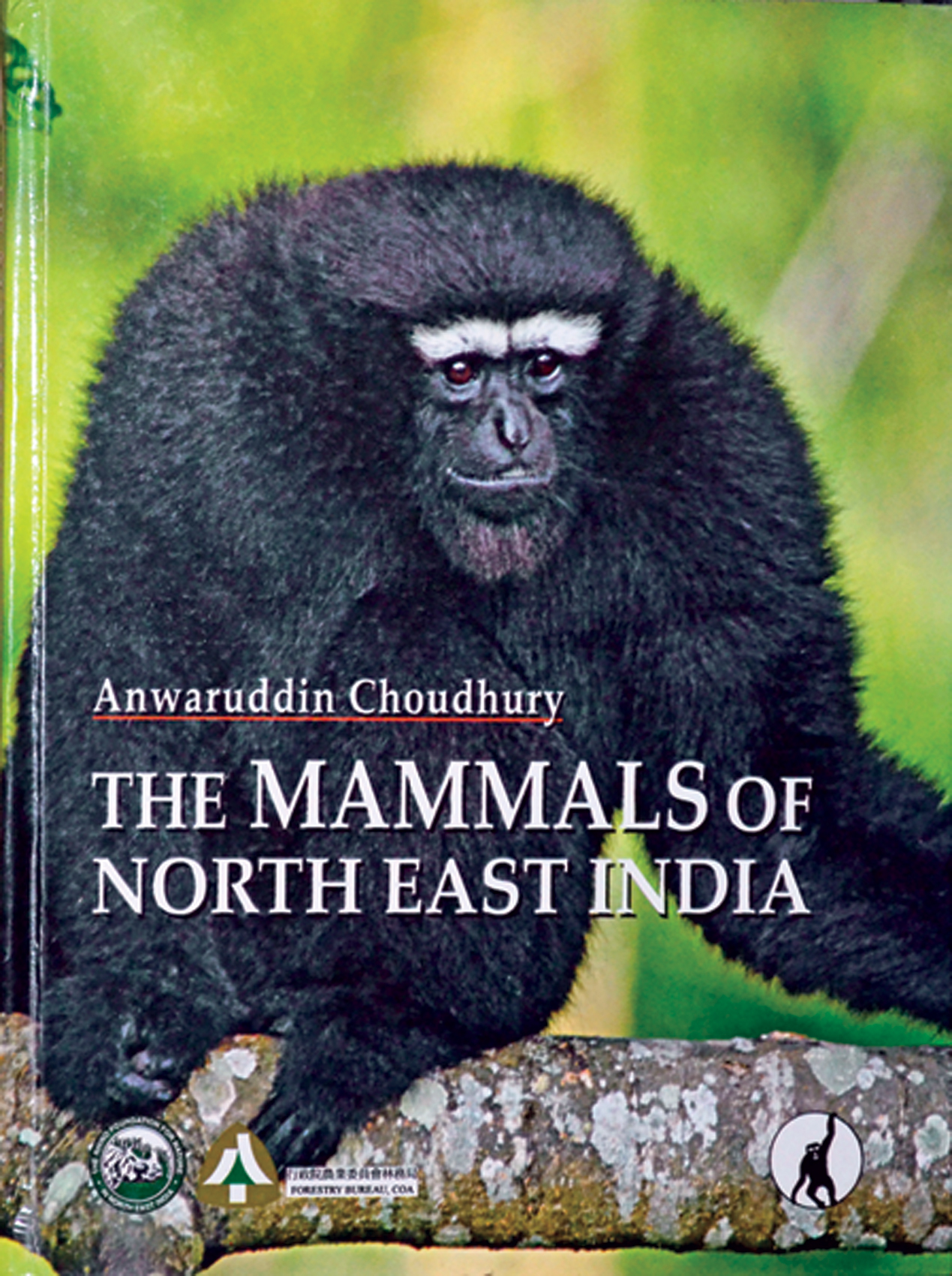

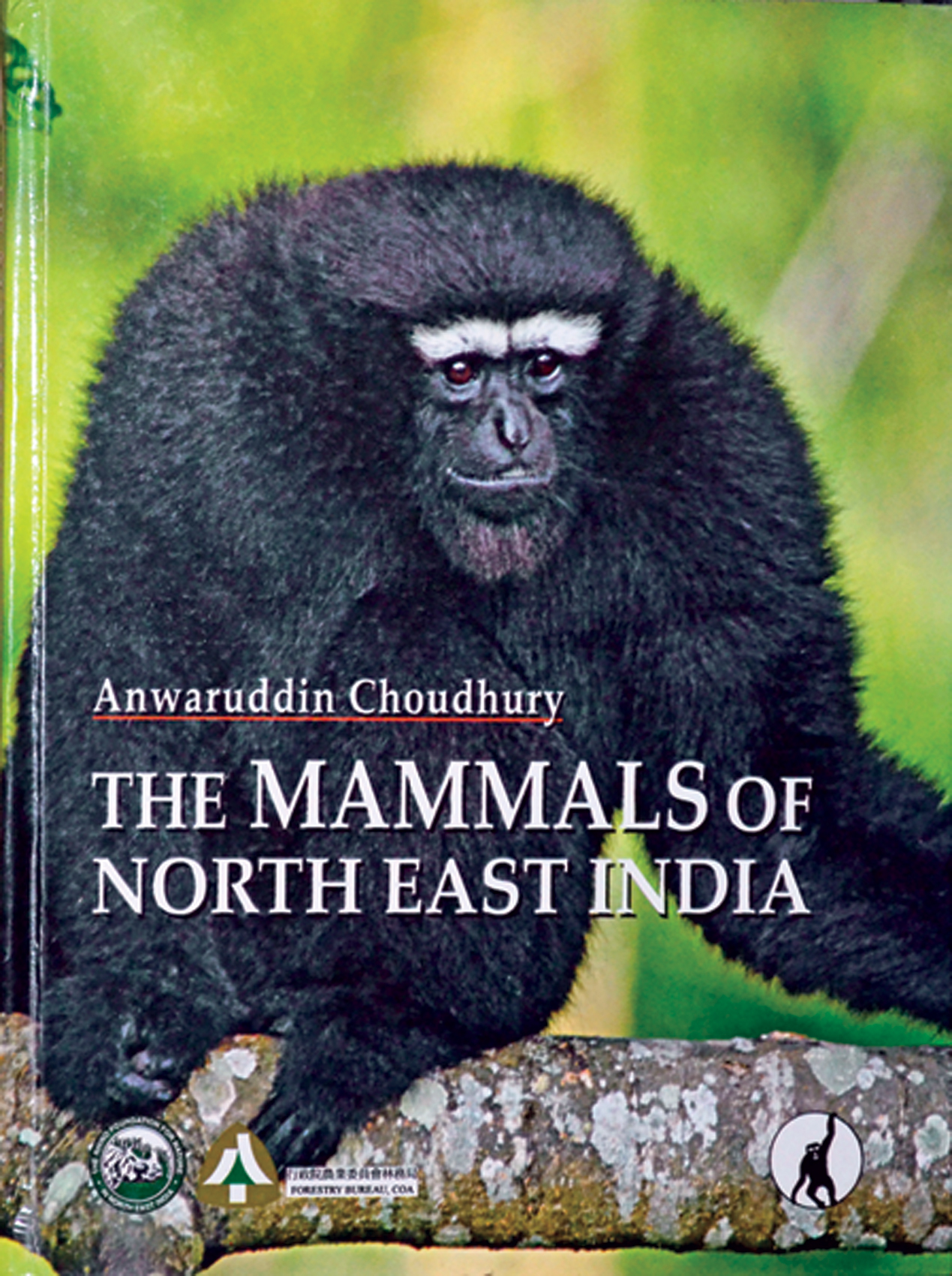

The Mammals of Northeast India is one of the several books authored by Anwaruddin Choudhury about wildlife in the region.

Photo Courtesy:Anwaruddin Choudhury

Awards have come your way for all the work you have done, but what is it that gives you the greatest satisfaction when you close your eyes, just before falling asleep?

It’s a very long list of dreams! First, the inner satisfaction of knowing that I have over four decades of research and conservation work under my belt! All the sanctuaries and national parks I managed to get declared. And the opportunity to implement my own recommendations, after convincing the Forest Ministers of Assam – late Nagen Sharma and Pradyut Bordoloi… and such exemplary senior bureaucrats as L. Rynjah.

I often retrace ‘lost trails’ walked in the most remote valleys of the Eastern Himalaya and Mishmi Hills. I replay the close shaves I have had with the wild elephants and buffaloes I live to protect. I love nights interrupted by local guides, guards, rangers, and others who live each day of their lives in the wild.

But worries too come to mind. The future of the many new species and subspecies of mammals that people like me have listed and many that may vanish without us even knowing they were there. I ponder the inevitability of being unable to walk tough trails up and down steep valleys in remote areas. Lots of memories and no regrets! But the darkest thoughts are those that force me to confront the reality that the leaders of our world, as evidenced from the outcomes of COP26 in Glasgow, just do not understand that their battles against nature are all doomed to fail. And that the heaviest price will be paid in innocent human and non-human lives lost.

Any advice for the young?

Stay curious, have faith and never give up. You will not lose until you give up, because nature has the ability to auto-repair the damage your elders are inflicting on our planet.