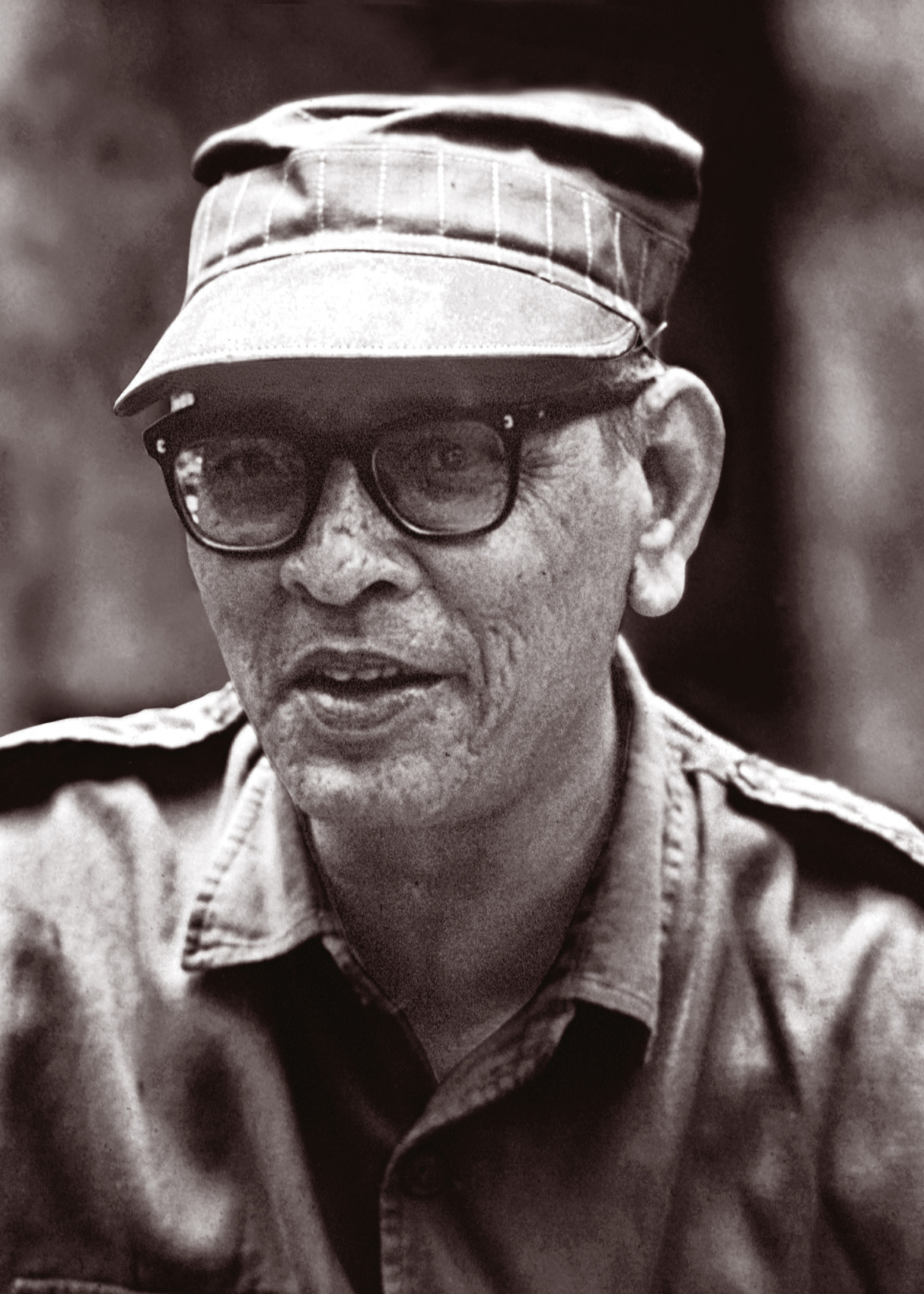

M. Krishnan - (June 30, 1912 - February 18, 1996)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 30

No. 8,

August 2010

A Tribute by Bittu Sahgal

The average educated adult knows little or nothing of the teeming plant and animal life of the country, and cares less. Livestock does not interest him, and the world is to him a place which holds only human beings. He can never make friends with a hill or a dog, and if he has no one to talk to, no book to read, and no gadget to turn and unturn, he is quite lost. School education is solidly to blame for all this. - M. Krishnan

I first met him in early 1981. After a quiet, forest-morning drive through Ranthambhore, I was sitting alone at Jogi Mahal, picking at my breakfast, looking out across the exquisite Padam Talao lake, when Madhaviah Krishnan, naturalist, writer and god of photography, walked over to my table and sat down.

Keen naturalist and a stellar writer, M. Krishnan was known for his popular column ‘Country Notebook’ in The Statesman. His work earned him a Fellowship from the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund to study the mammals of Peninsular India. He was one of India’s finest conservationists, dedicating a lifetime of passion and energy to studying, photographing and writing about wildlife.

Photo: T.N.A. Perumal

Before me were spread 40 or 50 very average, full colour, wildlife images that I had taken on a previous trip to Ranthambhore. Embarrassed, I tried nonchalantly to shove the images back into my bag, but heard him gently ask: “Yours?" as he began to flip casually through them. Five minutes later, he picked one out, handed it to me and placed the rest face down on the table. It was a pair of back-lit langur infants I had caught mid-leap as one tried to grab the others tail under a low-hanging branch of Jogi Mahals famous banyan tree.

Always economical with words, Krishnan said: “One in 50 is not a bad average. You should try shooting in black and white." He then proceeded to ignore me for the next couple of hours as he sat, writing notes, checking equipment and generally making sure I did not breach the wall of isolation he created around himself. He had an eye for the image. The one he selected was used by me to launch Sanctuary Asia a few months later and down the years, in his unique, minimalistic way he helped the magazine to set the bar for content, including texts and photographs.

Born in Tirunelveli, M. Krishnan was a product of the Hindu High School and Presidency College. Not best known for his academic brilliance, he nevertheless notched up a BA and a law degree, but eventually carved a secure niche for himself where his heart took him - as a freelance writer and artist. A keen naturalist, Krishnan had a more than a casual interest in botany, mastered in the course of field visits to the Nilgiri Hills in the company of a scientist called Professor P.F Fyson. After running through several jobs, none of which really interested him (Public Relations Officer for All India Radio, Political Secretary to the Maharaja of Sandur!), he honed in on a writing career that was to span several decades. Recognising his immense potential, Krishnan was awarded a Fellowship from the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund in the mid-1960s for an ecological survey of the mammals of peninsular India. A prolific writer, I cannot understand to this day why just two (utterly brilliant) collections of his writings were published in his lifetime - Jungle and Backyard and Nights and Days. Some say he wrote best in his native Tamil, but to readers such as I, who grew up reading Krishnans ‘Country Notebook, in The Statesman, Kolkata (published for 45 years from the 1950s), he was a magician who could cast nature-spells in the English language.

Inside the compartment it was crowded and close, and outside too the afternoon was muggy. I bought a ‘sweet-lime at Jalarpet Junction to assuage thirst and lassitude, and balanced it speculatively on my bent knee. Would it be bitter, would it be weak and watery, or would it be sharply satisfying? A hairy grey arm slid over my shoulder, lifted the fruit off my knees, and disappeared, all in one slick, unerring movement. I jumped out of the compartment, and there, perched on the roof of the carriage, was the new owner of the sweet-lime - a trim, pink-and-grey she-monkey, eating it. (Monkey Versus Man, Natures Spokesman, M. Krishnan, Oxford, Edited by Ramchandra Guha)

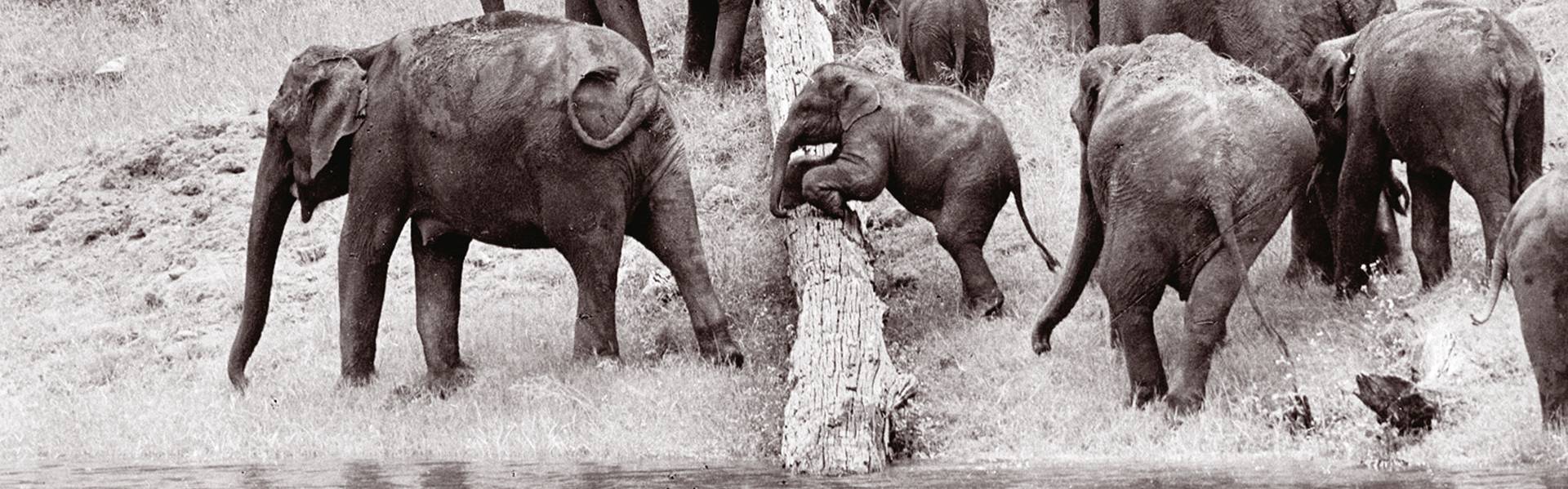

At dinner around a fire that evening, Fateh Singh Rathore suggested I ask M. Krishnan to write for Sanctuary Asia, the magazine I had decided to publish. Unsure whether the magazine would even see the light of day, it took three days of gentle, but persistent cajoling to get Krishnan to even agree to write: “I will do it, provided you understand that an Editors job is to get good writers to write, not to try and improve them. Nothing gets cut and nothing gets added." Awestruck, I agreed. Curious about how I had hoped to finance a wildlife magazine, he asked some straight forward questions not out of curiosity, but concern - “Are you a rich man? Have you any experience with publishing? Is this a whim, or will you stay the course over the years?" This done, he went on to underscore the vital need for a magazine of the kind I described, written for the ordinary reader, but imbued with the accuracy that comes with both science and field experience. The one piece he wrote for Sanctuary in January 1982, simply titled ‘The Indian Elephant, Elephas maximus, remains one of the finest I have ever had the pleasure of publishing (not editing!). An extract:

Given sufficient lebensraum to suit their habit of ranging far along elephant-walks, and freedom from human disturbance and predation, elephants have no problems and will create none for us, but this desirable state just does not obtain at present and seems unlikely of attainment in the future. When they find their familiar trek routes blocked by men and are confined to an inadequate tract, the disturbed animals become nervy and panic and consequently wander about aimlessly, often turning hostile to men. Further, though they have been long protected by legislation, poaching for ivory has taken a heavy toll on them and has added considerably to their sense of insecurity and their aggressive response to humanity.

M. Krishnan's prophetic words, written three decades ago in Sanctuary ring even more true today as elephants are running out of space: Given sufficient lebensraum to suit their habit of ranging far along elephant-walks, and freedom from human disturbance and predation, elephants have no problems and will create none for us, but this desirable state just does not obtain at present and seems unlikely of attainment in the future.

Photo Courtesy:The Estate Of M. Krishnan

Krishnan was an original thinker with a great respect for history and natural history. A loner in many ways, he never hesitated to share his knowledge or experiences with those less informed, provided he was assured that their interest in wildlife was genuine. One of his simplest lessons to me, offered I suspect only after he was convinced of my undiluted interest in wildlife, remains central to my enjoyment of nature three decades after I first met him. “If you want to enjoy wildlife, then look and listen. Observe behaviour. Do not rely merely on books and other peoples narratives. Try to understand why an animal does what it does. Over time natures ways will become familiar." He practiced what he preached. He wrote in Sanctuary from first-hand observation:

Elephants feed on renewable and periodically renewed plant parts, which get replenished by fresh growth. They consume a wide variety of fodder (the aerial shoots of grasses and bamboos, foliage and green twigs, herbaceous stems and bark, aerial roots, fruits and even some flowers) and need extensive, varied terrain to suit their far-ranging habit and seasonal variations of vegetation. This is why, although they are the largest land animals and need about 200 kg. of green fodder each day; no plot of vegetation anywhere in India has so far been destroyed by wild elephants.

About Krishnan it could rightly be said that “he was a legend in his lifetime." He served for years on the Indian Board for Wildlife and the Steering Committee of Project Tiger, he wrote letters to Editors of newspapers, even though he had scant respect for them (“Yes it is a mugs game all right, writing letters to the Editor. Sometimes I wonder why I play it), he wrote passionately about “ecological patriotism" and was more scathing and pungent in his attack on the ecological illiteracy of the Planning Commission than any of todays critics. He fought with all the power in his pen against those who introduced exotic plants such as Croton bonplandianum (water hyacinth) and Prosopis juliflora (what he called the pestilent mesquite) into India. And he had nothing good to say about those who described the Himalaya as the ‘Himalayas. Was he opinionated? Yes. Strongly so. Was he brusque and ascerbic? Yes. He found it impossible to suffer fools. But was he mean and vicious? Never.

All I have done above is provide Sanctuary readers the briefest glimpse into my perception of M. Krishnan. Others including Ramchandra Guha and Gopal Gandhi have written handsomely about him in great detail. Yet, few can aspire to fully encapsulate the immense canvas of this intellectual giant. Because he was such a meticulous chronicler of his truths, long after he has departed, he continues to guide those who have the wisdom to look into the past to chalk a way through future ecological minefields.

It would be fitting to let M. Krishnan have the last word. This is what he writes in an essay on ‘Ecological Patriotism:

At times a profound truth is embodied in a jocular saying, and the classic definition of a virgin forest as a tract where the hand of man has never set foot is such a saying. Provided they are of adequate area, all manner of wildlife tracts in our country have the potential to recoup if left strictly alone, even if now heavily depleted.