Loss and Hope

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 40

No. 4,

April 2020

By David Quammen

This is a small essay on the subject of birds, and loss, uncertainty and hope. I intend it to be helpful but not delusive; my goal is candor, but not gloom. To enliven it, I’ll insert a beautiful snake. And I will bring in a few words from a brave, forceful woman – all right, my wife – as a sort of contrapuntal line, because she disagrees with me so usefully on some of this, and because somewhere between the two of us, Betsy and me, perhaps you’ll see the intellectual and psychological terrain that you occupy yourself.

Vanishing Birds

We live, as you well know, in an age of staggering losses: losses of species, losses of populations, losses of biological diversity within populations, losses of habitat, losses of resilience within degraded ecosystems, losses of ice, losses of the climatic conditions necessary for biological communities and individual creatures to survive in place, losses of the connectedness that would allow them to move and losses of beetles, salamanders and whales. Losses of many thousands of koalas and wombats and other creatures in a single season of Australian fi res – the latest estimate, in fact, runs to one billion dead animals, counting insects. In this time of crisis, it’s essential that we help one another think about such losses in a way that doesn’t induce fatalistic paralysis. I’ll make my little attempt here, with a focus on birds.

Let’s look for a moment at North America, for which there are also some recently gathered numbers. A study by a team of scientists including Kenneth V. Rosenberg, of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, at Cornell University in the state of New York, has charted population changes among 529 species of birds in the continental United States and Canada, since 1970. Most of those species declined in abundance, some of them drastically. Category by category, it’s a gloomy drumbeat. Grassland birds declined. Migratory species declined. Warblers, blackbirds and finches declined. Shorebirds declined. Swallows and swifts declined. (Ducks and geese increased, thanks to the lobbying efforts of bird hunters and the hospitality of golf courses.) Tyrant flycatchers declined. The changes in half a century amount to a net loss in abundance of roughly 2.9 billion birds. The authors of this study remind us that such vast quantitative losses – not just the absolute losses of species to extinction – may have larger consequences. “Declines in abundance,” they write, “can degrade ecosystem integrity, reducing vital ecological, evolutionary, economic, and social services that organisms provide to their environment.”

Another study from last year conducted by the National Audubon Society found that 389 species of North American birds, amounting to two-thirds of the continent’s avifauna, are “at risk of extinction” due to climate change. Elsewhere in the world – India, Africa, the Amazon, Southeast Asia, and the Arctic – similar losses are occurring because of the same pressures, trends, and changes.

Studies have shown that bird species, such as this rare Yucatan Wren – and swallows, blackbirds, and swifts – have declined drastically in North America. They warn that 389 species, amounting to two-thirds of the continent’s avifauna, are “at risk of extinction” at the hands of climate change. Photo by: Shashank Dalvi

I’m no ornithologist myself, just a writer who reads the tea leaves of scientific publications and follows biologists through forests around the world. I suspect that many Sanctuary readers know their birds better than I do. (I’m a little stronger on-field identifications of insects and reptiles. I can tell a fritillary from a painted lady, and a skink from a gecko, much better than I can tell a tanager from a bunting.) But there are a few birds about which I do know a thing or two, and some of those birds represent stories of wonder and loss that resonate broadly through the whole network of dire problems and discouragements we’re currently facing – as conservationists, and as citizens of planet Earth.

One of the birds that I know about is the dodo, Raphus cucullatus. It was a gigantised and flightless member of the pigeon family, endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It went extinct in the late 17th century from a combination of causes. Those causes included sailors killing it for food, as well as rats, pigs, and monkeys eating its eggs. In other words, humanity arriving at Mauritius, for the first time, by way of European sailing ships, had doomed it. A giant flightless pigeon that had lived fine for perhaps a million years, eating fruit, laying its eggs on the ground, bothering nobody – not stupid in any sense, so far as we know, despite that “dodo” reputation – was exterminated quickly by the advent of people and our pestiferous camp-following invasive species and livestock.

A painting of the now extinct Dodo bird. Photo: John Keulemans after Roelant Savery/ Public Domain

What Extinction Looks Like

Twenty-four years ago, in 1996, I published a book on the subject of evolution and extinction, entitled The Song of the Dodo. It focused especially on islands and island-like fragments of protected landscape – such as national parks and reserves. As the title suggests, I used the dodo as an icon for the big themes I was exploring. Those themes included biological diversity, losses of biological diversity, and hope in the face of loss. The dodo itself wasn’t my main subject, just a representation, but at one point I did describe the history and natural history of this creature Raphus cucullatus – its life, its song, and its death.

Nobody knows exactly when the last dodo died in the wild. The proximate cause, and the exact place and time of the final death, are uncertain. We only have record of the last known killing of dodos by people, which occurred in 1662 on a small islet just offshore from Mauritius and reachable at low tide, where a group of marooned Dutch sailors including one Volquard Iversen (who later told the tale) caught, killed, and ate several dodos. No living dodo was ever seen again, but that doesn’t mean that those few on Iversen’s islet were the very last. Mauritius at the time still had regions of unsettled forest, in the Black River Gorges (seen in the banner image above) and elsewhere. That’s the way it is with most extinctions. At the very end comes dearth of evidence, sadness, and uncertainty.

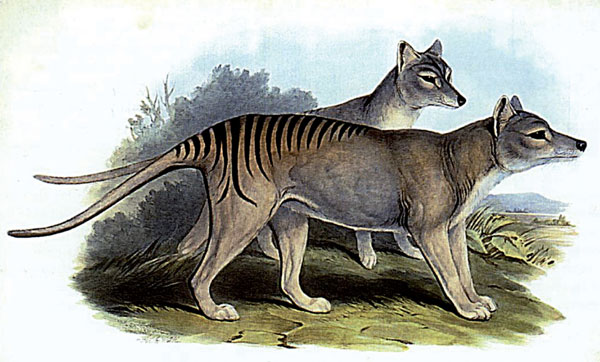

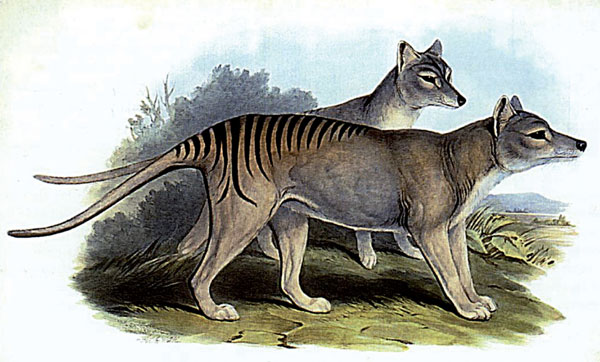

We don’t know the fate of the very last Tasmanian tiger – a carnivorous marsupial, more accurately known as the thylacine. Its end, like the dodo’s, is veiled in uncertainty. We just know that the last captive thylacine died on September 7, 1936, in the Hobart Zoo. We don’t know when the last passenger pigeon died in the wild – we just know that the last captive individual (her name was Martha, and she was likely the last individual, decades having passed since the last sighting in the wild) died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. And we don’t know the end of the story of the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker, a large and vibrantly coloured bird native to bottomland forests around the perimeter of the American South, until it seemingly disappeared in the 1940s.

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was declared extinct in the wild around 1936; reported ‘sightings’ in recent years have been inconclusive. Photo: John Gould/ Public domain.

To compensate for such gaps in knowledge, to clarify that final extinction usually results from multiple factors, and to try to make the loss of a species feel more real, I wrote a hypothetical scenario about the dodo itself in my book. The last bit of it goes like this:

Imagine a single survivor, a lonely figure at large on mainland Mauritius at the end of the seventeenth century. Imagine this fugitive as a female. She would have been bulky and flightless and befuddled – but resourceful enough to have escaped and endured when the other birds didn’t. Or else she was lucky.

Maybe she had spent all her years in the Bambous Mountains along the southeastern coast, where the various forms of human-brought menace were slow to penetrate. Or she might have lurked in a creek drainage of the Black River Gorges. Time and trouble had finally caught up with her. Imagine that her last hatchling had been snarfed by a feral pig. That her last fertile egg had been eaten by a monkey. That her mate was dead, clubbed by a hungry Dutch sailor, and that she had no hope of finding another. During the past half-dozen years, longer than a bird could remember, she had not even set eyes on a member of her own species.

Raphus cucullatus had become rare unto death. But this one flesh-and-blood individual still lived. Imagine that she was thirty years old, or thirty-five, an ancient age for most sorts of bird but not impossible for a member of such a large-bodied species. She no longer ran, she waddled. Lately she was going blind. Her digestive system was balky. In the dark of an early morning in 1667, say, during a rainstorm, she took cover beneath a cold stone ledge at the base of one of the Black River cliffs. She drew her head down against her body, fluffed her feathers for warmth, squinted in patient misery. She waited. She didn’t know it, nor did anyone else, but she was the only dodo on Earth. When the storm passed, she never opened her eyes. This is extinction.

So Much For Loss. What About Hope?

Hope is crucial to everything we care about – every battle we fight, every rescue we engineer, every act of mitigation we perform. It’s not a psychological condition, hope. It’s a courageous act of will. It’s a resolution. If we have children and grandchildren - or even If we don’t have offspring, but we do have love and concern for our younger fellow humans – then we bear a severe responsibility to find and convey hope.

I once wrote another dire prognosis on the state of our planet, which appeared as an essay in Harper’s Magazine, back in 1998, and the first sentence of that piece said: “Hope is a duty from which palaeontologists are exempt.” What I meant was that palaeontologists study the fossil record to learn of life forms, evolutionary transitions, catastrophes, and extinctions that have already occurred. They are the coroners of biological diversity. Hope is a duty from which they are exempt because all those losses have already happened. But of course I was exaggerating for effect. When a palaeontologist finishes work for the day and heads home, she or he has every bit as much duty to be hopeful as the rest of us.

Why? Because without hope, there is no useful action. There is no determination to save what can be saved. There is no last-ditch effort to turn the trend, to resist the seemingly inevitable, to make the impacts of climate change and habitat loss and conflict between humans and predators – and all the other forms of degradation of life on our planet – turn out just a wee bit, or more than a wee bit, less ugly than they might be.

But hope is just a word, too, and I am fully aware that others may interpret its meaning – its value, its necessity – in ways different from mine. My own wife and I discuss this in deep, earnest conversation around the virtual campfire in our living room, as we share cocktails and the quiet company of three large dogs and a cat each evening before dinner. (The snake that I’ve promised? That’s our ball python, named Boots, who lives in a tank in my office and doesn’t attend cocktail hour. But his sinuous movements around the tank, or climbing the bookshelves when I let him wander, keep me mindful of the ineffable beauty of wild creatures.) Betsy is 20 years younger than I am, so we both expect that she will see and experience losses that I don’t. She will likely witness dire and horrific consequences of the current trends that I will be spared by my timely, or untimely, death. That prospect makes her scared, angry, sad, and yes, hopeless. She also has written eloquently, in View from the Gazebo about what she sees as the dichotomy of hope and clarity. “To blithely hope is to ignore the reality of this moment,” she has written. And this:

To stop saying “hope” isn’t a bad thing. Hope is just a word that makes us feel better, like “thoughts and prayers.” It’s an abstraction at a time when we need action. We need to be more muscular than hope and we need to be clear-eyed. The world and its inhabitants deserve this.

She’s a fierce, smart, passionate, opinionated woman. Luckily for me, this difference in viewpoint on hope and “hope” is a matter of definitions and emphasis, not outright disagreement, or the conversations at our little campfire might set the house ablaze.

Hope is Where the Heart Is

However you define it, hope is where you find it – in the forests of Tasmania, if you’re a diehard on the thylacine and believe it has survived – or in the schools where you teach, the organisations you support, the rare leaders (Greta Thunberg comes to mind) who inspire you, the community of neighbours among whom you live.

Or you find it in other, unexpected sources. For instance: I recently got an email from a man named Michael D. Collins. He’s a mathematician at the United States Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC. He’s also a bird lover. In particular, he’s in love with the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker Campephilus principalis, a species presumed extinct since the 1940s. (There was also a Cuban Ivorybilled Woodpecker Campephilus bairdii, now also believed to be extinct.) The precise date and immediate cause of extinction of the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker is uncertain – as it is for the dodo. That similarity was more than coincidental for Mr. Collins: He was writing to me, he said, because he had read The Song of the Dodo, and it helped him develop a passion for conservation. So, I felt responsible to give him, at least, a fair hearing.

One of the rarest birds of America, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, has not been seen since 1944, yet

some ardent optimists believe that these large woodpeckers still survive deep within the forests of

Louisiana, Florida and Arkansas. John James Audobon/ Public domain.

Mr. Collins is possessed by a fervent and stubborn belief that the American Ivory-billed Woodpecker is still alive – surviving, a discreet and elusive population of big, black, white and red birds, in the Pearl River swamp of southern Louisiana, just east of the delta where the Mississippi river empties into the sea. It might also abide in certain remote, bottomland forests of Florida and Arkansas. He has many hours and days of observation, from his specially outfitted kayak. He has the echo of ivory-bill calls, or what he thinks were ivory-bill calls, in his head. He has, as you’ll see, hope.

This is all a new chapter to an old story; there have been “rediscoveries” of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker before, none of which has been proved. Nobody has a good recent photo. Nobody has ironclad evidence. I remembered all that when I got this recent email from Collins. He was frustrated. He had published his findings in an obscure journal – obscure to bird people and conservationists, anyway – called Statistics and Public Policy. He made, in that paper, an argument from probability theory: that the existing evidence of sightings fits the ivory-bill better than any other bird, and that the absence of evidence (a clear photo) is unsurprising given its admitted rarity. But he was having little luck persuading biological journals to publish his results, nor academic ornithologists to accept them. What he said to me, at the end of his first email, was this:

"Other scientists have studied the data and found it convincing, but there is a need for a high-profile scientist to take an interest in this bird and convince the right people to open their eyes. That is the only hope I can see for putting an end to the folly and politics that have undermined this conservation issue for several decades."

Then he asked, “Would you be willing to have a chat? I am hoping that you might have some ideas about what can be done in the interest of this magnificent bird.”

The italics are mine, but the hopes were his. I told him: I’ll mention it when I can.

And so, I mention it here. Do I think that the Ivory-billed Woodpecker has survived? I don’t know. Do I consider it one of the pre-eminent conservation issues of the present moment? No. Not while climate change and habitat loss and the other destructive factors are putting thousands of other species and whole ecosystems at immediate risk. Not after we’ve lost those 2.9 billion American birds since 1970, and while 389 avian species are at risk on the North American continent, plus many more in India and still more around the world. Not while the black rhino, orangutan, hawksbill turtle, Javan rhino, Sumatran elephant, eastern lowland gorilla and Bengal tiger are indisputably alive but critically endangered. We’ve got lots of concerns more tangible than the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. We’ve got lots of species, lots of diverse fauna and flora, and ecosystems that definitely can be preserved.

But Michael D. Collins is a valuable reminder and exemplar to all of us. It takes hope – fierce, obdurate hope, against the odds, against the winds of convention and complacency – to save these precious life forms we want to save. We should be aware of his fight and honour his zeal.

And as we face these difficult, dispiriting challenges, we might remember too a famous stanza from the American poet Emily Dickinson, written in 1862 and never published during her lifetime: “Hope” is the thing with feathers – That perches in the soul – And sings the tune without the words – And never stops – at all.

(Adapted from: New York Audubon Awards Talk, November 6, 2019)

David Quammen is an award-winning writer, he is a contributing editor at National Geographic and has authored several fiction and non-fiction books. His writings on science, nature, and travel intelligently weave hard facts with delightful wit.