Jivanayakam Cyril Daniel (July 9, 1927 - August 23, 2011)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 31

No. 10,

October 2011

By Bittu Sahgal

As with most of the stalwarts of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), when I approached J.C. Daniel with my hare-brained idea of starting a full-colour, wildlife magazine way back in 1980, he gave me a polite hearing, proffered advice about how difficult the task would be and then politely waited for me to finish the cup of sweet tea and biscuits he had ordered for me before suggesting that he needed to return to his pile of papers. “Just be sure you have enough cash available,” he cautioned, adding that “popular wildlife writing was difficult enough to publish in black and white and colour might just be asking for too much.” I left his room, quieter than when I entered, and on an impulse he walked me to the stairs, genuinely anxious that a young and inexperienced man’s enthusiasm was getting ahead of him. “You must always feel free to seek my help,” he called out to me as I looked up at him from half-a-floor down and nodded.

Assailed by doubt, I left Hornbill House, wondering what I had let myself in for and whether I would end up pauperising myself for what everyone felt was a ‘worthy’ but lost cause (publishing a magazine, not protecting wildlife!). In the event, J.C. was among those such as Dr. Sálim Ali and R.E. Hawkins (Jim Corbett’s editor), who generously gave of their time and their knowledge, holding Sanctuary’s hand through the decades.

The BNHS soon became my second home and one thing led to another until I began to serve on the Executive Committee of the BNHS. This brought me still closer to the greats who I held in such high esteem and whenever a new Sanctuary issue emerged, I would troop in with copies fresh off the press for J.C., the Old Man, Humayun, Hawk and, of course, the customary two copies for the Society’s library.

J.C. never ever mentioned it, but I am almost certain that he and the Old Man had spoken to each other about Sanctuary and had taken it upon themselves to help me navigate the initial quicksand of publication. Both were always at the end of the line, offering advice, suggesting stories, pointing to books I should refer to from the library.

As the years passed and Sanctuary became firmly established, J.C. and I would spend time discussing Darwin and evolution, or the rationale for shikar and the imperative of collecting skins for posterity. One constant refrain of his, and Dr. Sálim Ali’s and Humayun Abdulali’s and K.S. Dharmakumarsinhji’s was the pathological need to stay accurate, something they all believed was at a discount where most Indian wildlife texts were concerned.

A LIFE WELL LIVED

J.C. joined the BNHS as a research assistant in 1950 and within a year he found himself accompanying Dr. Sálim Ali on an ornithological trip in search of the White-bellied Tree Pie to Chikaldhara (now the Melghat Tiger Reserve). He never looked back. For six decades, it is doubtful that much transpired within the hallowed walls of the Society without J.C.’s knowledge. It would be equally doubtful that anyone who passed through the Society, as a member, staff member or researcher remained uninfluenced by this dignified, unbending man whose life was governed by the principles of altruism and service.

When someone like J.C. dies, he takes an entire library of knowledge and experience with him. Fortunately, a great deal of this he did put down for posterity in print and it lies there waiting to be discovered by those who have the inclination and the patience to pour over thousands of pages.

When I was little more than an enthusiastic, amateur-wildlifer in the mid-1970s, J.C. Daniel was already a robust pillar of the Bombay Natural History Society, where he rose to serve, first as Curator, then Director, between 1960 and 1991. He was a Vice President of the Society when he succumbed to cancer in Mumbai at the age of 84.

My earliest recollections of J.C. were of a man with perfectly-combed, jet-black hair, bent over one or other of the priceless tomes in the BNHS library. Courteous to a fault, and quick to smile, he was anything but a daunting figure, particularly since his ready wit and helpful demeanor would put visitors young or old at ease within seconds of walking into his book-lined room.

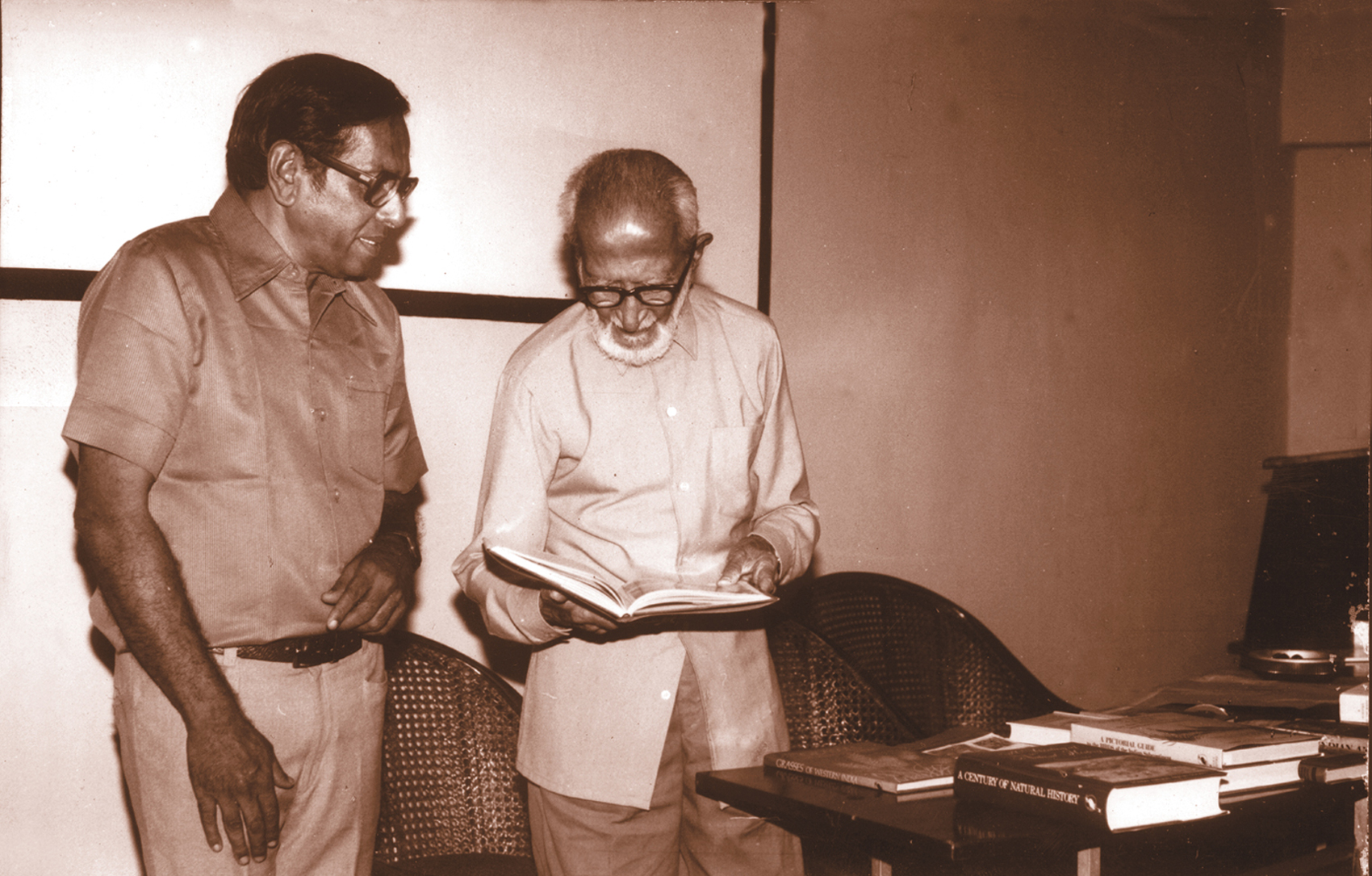

Dr. Sálim Ali releasing The Book of Indian Reptiles, which took J.C. 23 years to write!

Photo:J.C. Daniel

TRUE TO HIS CALLING

Erudite, learned, meticulous to a fault, J.C. was a guide for as many as 11 PhDs. and seven MScs when I interviewed him for Sanctuary way back in the year 2000. Ironically he never wrote a PhD thesis himself! This is what he said when I asked him why:

In my book a Ph.D. can only be earned if you dedicate 24 hours a day, seven days a week from start to finish. Considering as how it took me 23 years to finish my reptile book, I could not possibly have given it that kind of time priority. In more ways than one perhaps I consider myself to be a naturalist, rather than a scientist. I would say, for instance, that there are two or three elephants in a range, or one or two hatchlings in a clutch of five might survive. Modern scientists in search of elusive accuracy often suggest numbers like 2.39 elephants or an average of 1.65 hatchlings! Sometimes their reliance on sheer statistics is too literal for my liking.

That sums up the approach of the man whose attitudes and outlook were largely shaped by naturalists of yore such as ornithologist Dato Lok Wan Tho and Dr. Sálim Ali. In fact, even as he lauded science as the backbone of field biology, he remained critical of the blind adherence to it to the day he died.

He never tired of saying that the finest naturalists had what people might call ‘doubtful basic qualifications’. In this list he included Charles McCann, botanist, mammalogist, herpetologist and entomologist, the legendary S.H. Prater and even Dr. Sálim Ali (who was eventually awarded an honorary doctorate). But such people had a fine scientific temper J.C. hastened to add, and were the very backbone of the BNHS.

I don’t think I ever knew a time that J.C. was not either writing, or editing a manuscript. With his thick horn-rimmed glasses and focused concentration, he was the quintessential academic, pouring over two or three books at a time, note pad on the ready, scribbling away. Natural History and the Indian Army was a recent book he edited (together with Lt. Gen. Baljit Singh), which he called a tribute to the Indian army which added much to the natural history knowledge of the subcontinent and drew the attention of the government to the urgent need to protect vanishing species and their habitats. The very last book he midwifed was the BNHS Field Guide on Indian Birds, as recently as July 30, 2011.

I often wondered how J.C. managed to carve himself such an indelible niche in the BNHS, which in recent decades had been so dominated by ‘birdmen’. In my head J.C. was and will remain ‘an elephant man’ though there was no doubt at all that everything about nature interested him. Little wonder the books flowed thick and fast – Petronia, a commemorative collation of articles by Dr. Sálim Ali, which J.C. edited with Gayatri Ugra and which was published on the ‘Old Man’s’ 100th birth anniversary; A Week with Elephants, edited with Hemant Datye, from papers submitted for a seminar on elephants when Project Elephant came into being, his Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians, A Century of Natural History, The Leopard in India and one, interestingly titled Casandra that was culled from his writings on conservation issues published in Hornbill.

As the Editor of the Journal of the BNHS for 38 long years from 1965-2003, J.C. became one of the world’s best known experts on the natural history of the Indian subcontinent. Writers, fresh and established, wrote to him constantly seeking to be published in one of the world’s most respected scientific journals. He was called upon to opine on all manner of issues concerning natural history. Little known to most, he also played a key supporting role for both Dr. Sálim Ali and Zafar Futehally when they threw their considerable reputations behind the need to establish Project Tiger.

A RICH LEGACY

One day someone will sit and document the prodigious output of J.C. Daniel; the field projects he helped start to study animals like the wild buffalo, elephant, blackbuck, tiger, Nilgiri tahr, saltwater crocodile and the golden gecko which he was credited with rediscovering after it had been presumed extinct for over a century.

For several decades J.C. headed some of the BNHS’ most prestigious research projects, often with the support of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, one of the Society’s key funding sources. These took J.C. from Point Calimere, located to the extreme south of India, to distant Kashmir and from the arid Thar desert to the evergreen forests of the Northeast.

At the time of his death he was the Principal Investigator for an on-going study on the status of elephants in the Eastern Ghats of Karnataka. His service to wildlife was of that fashion. He was not your dyed-in-the-wool conservationist of the loud and garrulous kind. Soft spoken, yet firm, he in fact always advocated a sort of middle path that sought to avoid confrontation if possible. Not that he did not hold strong views. Consider his response when I asked him about the dams (then proposed, now underway) in the Northeast:

There cannot be a greater folly than the building of large dams in the Northeast. Quite apart from the impact of forests that are a treasure trove of biodiversity, the entire region is seismically active and the siltation rates would negate any imagined benefits in a few short years. The devastating Assam earthquake of 1952, which E.P. Gee then wrote about in the BNHS Journal, seems to have been conveniently forgotten.

To the day he died, his thoughts and dreams revolved around the BNHS whose scientific temper he tried to consolidate all through his life. I have no doubt that future historians will record his contribution to India’s wildlife as foundational.