In Memory of P.K. Sen Saheb

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 6,

June 2021

(August 4, 1941 – May 2, 2021)

By S.E.H. Kazmi

This perhaps is the most difficult assignment of my life. Writing the obituary of Prashant Kumar Sen or Sen saheb – my mentor, my hero. His journey onwards to happier hunting grounds has shattered so many of us. I am still coming to terms with his departure. I wonder, do men like Sen saheb truly die? Perhaps not. Perhaps they live on through their work, and in the hearts of all those lucky enough to have known them.

I first got to know Sen saheb way back in 1987 when I was a young probationer, fresh out of the Forest Research Institute (FRI), Dehradun and staying at the Bhalua Forest Rest House in then undivided Bihar’s Gautam Buddha Wildlife Sanctuary. One bright morning, the Assistant Conservator of Forests (ACF) of the Gaya Forest Division – the controlling division of the sanctuary – came to the forest bungalow and told me that a senior forest officer would be halting for lunch at the rest house on his way back to Ranchi from Patna. I was intrigued. It was very rare for any officer to visit this secluded bungalow in those days due to the raging Maoist insurgency in the area. Out of curiosity, I asked the ACF about this guest. He reverentially informed me that the gentleman was a towering personality within our department, very fond of wildlife, extremely protective of his juniors and subordinate staff. “Bas daant te bohot hain (He scolds a lot though), but his anger is superficial,” he chuckled and added that he never harms anybody using his ‘pen’. Immediately I knew that there was something very different about this officer. Eventually, our guest arrived – a tall, well-built man immaculately dressed in crisp white trousers and a shirt. He got down from the vehicle at the gate of the bungalow campus, received our salutes and greetings and walked. Oh! What a walk – quiet, leisurely and yet commanding respect. It reminded me of the walk of a tiger in his jungle. I have no qualms in admitting that I was absolutely overawed by his presence. After my initial introduction, he asked me if I stayed in this bungalow. “Yes,” I said. “Darr nahin lagta akele?” (Aren’t you scared all by yourself here?). I said no, and that in fact I really liked it here given the abundant wildlife around the bungalow and the quiet. He looked at me and just smiled.

Born in 1941 in Kolkata, P.K. Sen moved to Bihar in his youth. After a lifetime of protecting the forests of Bihar, he was appointed as Director of Project Tiger until he retired. He was honoured with the Padma Shri by President Pratibha Patil in 2011. A Sanctuary Lifetime Service Award was presented to him in 2002. Photo Courtesy: Richa Prasant.

Born in 1941 in Kolkata, P.K. Sen moved to Bihar in his youth. After a lifetime of protecting the forests of Bihar, he was appointed as Director of Project Tiger until he retired. He was honoured with the Padma Shri by President Pratibha Patil in 2011. A Sanctuary Lifetime Service Award was presented to him in 2002. Photo Courtesy: Richa Prasant.

I had a few more interactions with Sen saheb in the next few years, but I really got to know the officer and the man himself from 1992 when he became the Field Director of the Palamau Tiger Reserve (PTR). I had taken over the charge of Daltonganj (South) Division (now renamed as the tiger reserve’s Buffer Division) just a year earlier, and my batchmate A.K. Pandey was the Deputy Director, Project Tiger Division (now renamed as the tiger reserve’s Core Division). In fact, there is a funny little incident related to his becoming my boss. In late 1991, the transfer of the Field Director at PTR – the very accomplished R.C. Sahay saheb – was due. I met Sen saheb in Ranchi – he was the Conservator Headquarters there at the time. I casually mentioned another officer’s name and said that if the said officer were posted as FD of Palamau it would be good. He frowned and in his typical mock-scolding andaaz asked me, “Do you think that is the best boss you can get?” I was puzzled but he didn’t elaborate. About a month later, he joined as Field Director, PTR.

Sen saheb was the finest conservationist I ever knew, and used to often buy trouble with the highest and mightiest. Let me narrate the story of Mandal Dam, now much in the news. When the irrigation department wanted to close the dam’s sluice gates, we initiated field operations to stop the illegality. However, it was Sen saheb who not only gave his DFOs administrative cover but also defended our case at every possible forum. In fact, when the pressure became too much, he advised me to go on leave but not succumb to the pressure. He had perfected the art of ‘working the system’ for conservation goals, and would often shoot explanatory letters to me as was instructed by the senior bureaucratic apparatus. However, as soon as the letters had been dispatched to me, he would call me to his chamber and tell me, “Whatever letters I have sent you, you just ignore them and stick to the law.” He would even go on to defend our case in front of the Chief Minister himself and that is how we eventually managed to obtain a moratorium against the closing of sluice gates until all the clearances were granted by the Government of India.

Sen saheb gave his DFOs free reign to go after poachers, and consequently we busted a number of poaching rackets under his tenure. If it was not for Sen saheb’s unstinting support and leadership, a large part of Kutku range forests would have been sacrificed to mining, while another large portion of Palamau would perhaps have become an Army Firing Range – a proposal mooted in the 1990s which would have become a reality had it not been for him giving his DFOs a free hand to stop it and take care of all the necessary administrative manoeuvrings.

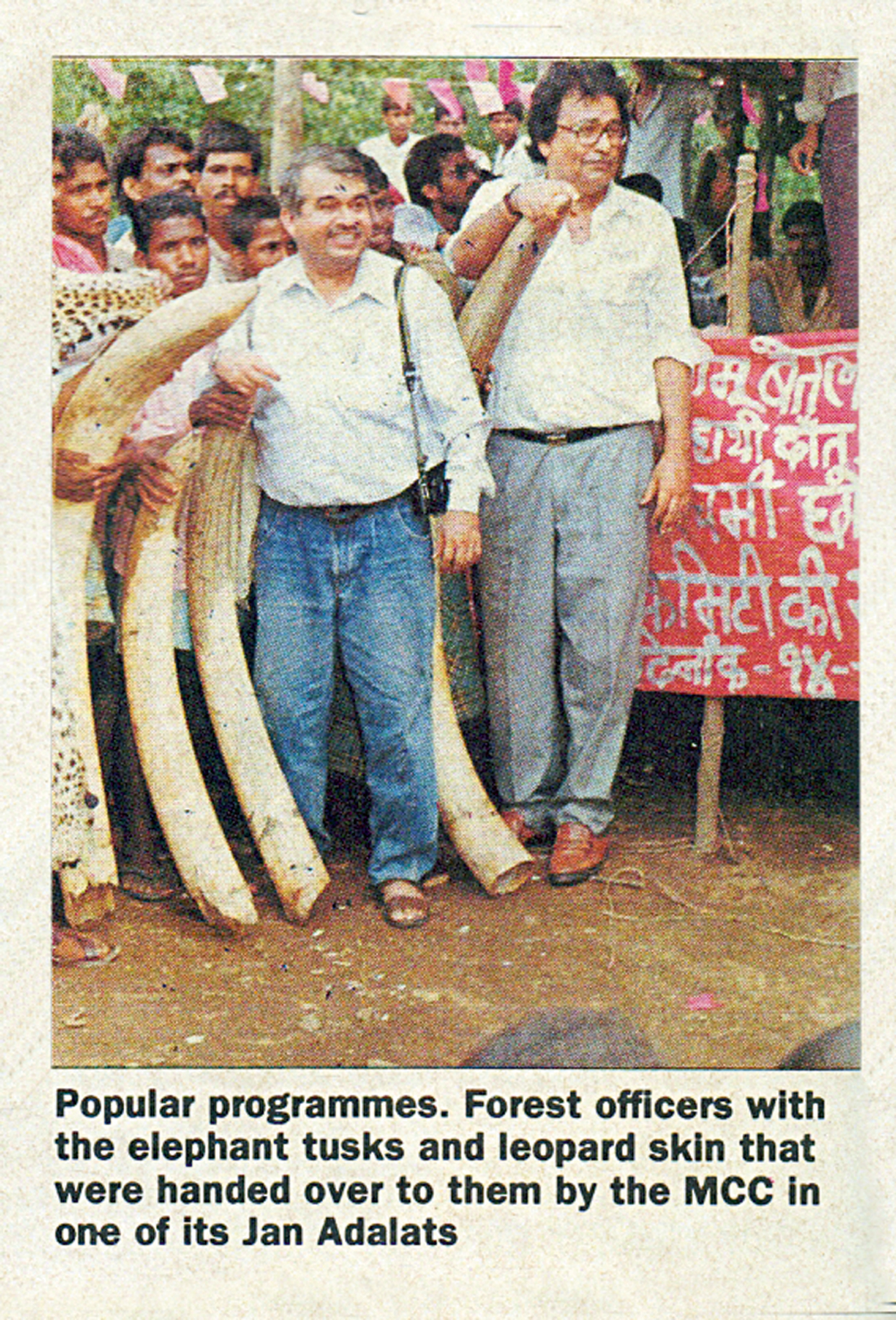

The author S.E.H. Kazmi and P.K. Sen with massive elephant tusks and a leopard skin that they retrieved from the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) in 1995 at great risk to their lives. Photo Courtesy: Raza Kazmi.

The author S.E.H. Kazmi and P.K. Sen with massive elephant tusks and a leopard skin that they retrieved from the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) in 1995 at great risk to their lives. Photo Courtesy: Raza Kazmi.

I shall narrate one more remarkable instance demonstrative of his fearless and protective nature – almost paternal in a sense – that I had first heard of all those years ago at Bhalua from the ACF. On the night of July 27-28, 1995, four tusks and one leopard skin were stolen from the Nature Interpretation Centre at Betla in PTR. Betla, the base range of the Project Tiger Division, was under Sen saheb’s direct control, though by that time he had been promoted to hold the additional charge of CCF in Ranchi and thus had to shuffle between Palamau and Ranchi. When he came to know about the robbery, he came to Betla and after the initial round of severe tongue lashing, he sat down on the stairs of the tourist canteen, called me and said, “Kazmi, dekho budhauti mein ye sab saala humre munh par kaalikh mal diya hai, isko theek karna hai,” (Kazmi, I have been embarrassed in my last years as an officer, we have to rectify this) and formed a crack team led by me (despite Betla not being under my jurisdiction) to recover the material. We later found out that the aforementioned stolen government property had been confiscated from the robbers by the outlawed Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) who were running a parallel insurgent government across the hinterlands of Chotanagpur plateau. In my initial meeting with them for negotiations, they wanted a senior officer and me to meet them on a certain date at a certain place to get the contraband back. When I informed Sen saheb of this demand, he did not even flinch and immediately agreed. And so the two of us went to a huge Jan Adalat called by the Maoist rebels where they handed over the four stolen tusks (137 kg.) and leopard skin. Sen saheb was worried that the police would come after me once this news became public. He instructed me to tell the police that I knew nothing about this entire affair and ask them to talk to the Field Director – as he was the one who had informed the government and police about this recovery – and he would handle it from there. He ensured that no harm came to us from the police.

Then there was also the lighter side of his personality that brings a smile to my face even to this day. Once, me and A.K. Pandey were chatting when we were summoned by Sen saheb. After the routine instruction he asked us what were we doing. Before Ashok Pandey could speak, I blurted out “sir, aapki buraai kar rahe the” (sir we were backbiting about you). He just gave us a look and did not respond but later, whenever he would meet us in the presence of other officers, he would always introduce us saying “these are my DFOs, they have no work except abusing me. And see the temerity of this joker [pointing at me] that he even tells me that they were backbiting.” My standard response would be “Sir, ab do gunaah ek saath thodi na kar sakte the, ek toh aapki burai aur dusra aapse jhoot bolna” (Sir, now we could not commit two sins on that day, could we – backbiting and lying to you about it). Everyone would have a good laugh. Sen saheb was such a great person that he never took anything to his heart. I also got to know during my time with him that his one weakness was a nice paan. So, whenever he summoned me and I knew I was about to get in trouble, I would ask my peon to place this special paan I knew Sen saheb liked on saheb’s table. I would then wait for a while, knowing he wouldn’t be able to resist eating the paan, and then go into his office. As expected, he would be enjoying the paan and after a few muffled words would dismiss me and by the time he was done with his paan his anger would dissipate. He eventually realised this trick however. So the next time the peon would come calling for me, I’d ask him, “has saheb begun having his paan?” to which he would reply, “hum diye toh table mein side mein rakh diye sahab jab bataaye ki aap bheje hain ye paan aur bole pehle Kazmi ko bolo report karne ko idhar uske baad paan khaenge!” [When I gave your paan to him he kept it on the side of his table as soon as I told him that you had sent it, and told me that I should ask you to report to his chamber right away and only then he would start having that paan!].

The author and P.K. Sen contributed tremendously to the conservation of the Palamau Tiger Reserve, one of the first nine to be declared in India. In a 2002 interview with Sanctuary, he said: “I was posted at Palamau in 1967. Anyone who has been there will understand why I fell in love with the tiger. These forests, made famous by Dunbar Brander, Sanderson and Captain Forsyth, did not merely seed my passion, they injected in me a desire to protect nature.” Photo: Aditya Chandra Panda.

The author and P.K. Sen contributed tremendously to the conservation of the Palamau Tiger Reserve, one of the first nine to be declared in India. In a 2002 interview with Sanctuary, he said: “I was posted at Palamau in 1967. Anyone who has been there will understand why I fell in love with the tiger. These forests, made famous by Dunbar Brander, Sanderson and Captain Forsyth, did not merely seed my passion, they injected in me a desire to protect nature.” Photo: Aditya Chandra Panda.

I have purposefully focussed on my memories with Sen saheb as I got to know him, for there are people who know of his many battles for conservation in Bihar before I joined the state in 1987, and of his herculean work during his tenure in Delhi as Director, Project Tiger, after he left Palamau.

As I remember my time with the great man, so many memories come flooding. How Sen saheb would go out of the way to help the frontline staff, how he would personally check on their welfare, how if anyone was sick, he would not only personally enquire of their wellbeing but always give them some money for treatment, and so much more. His ever-abiding love for good food was infectious and he was famed as a very generous host. He was such a larger-than-life figure for me, I could fill pages after pages writing about him. I have learnt so much from him, and the officer that I became was in no small measure due to his support, guidance and teachings during the formative first decade of my career. And so, while Sen saheb might not physically be around me anymore, he will continue to live on in my heart and his legacy will live on through the work of countless people he inspired and guided during his lifetime.

.png)