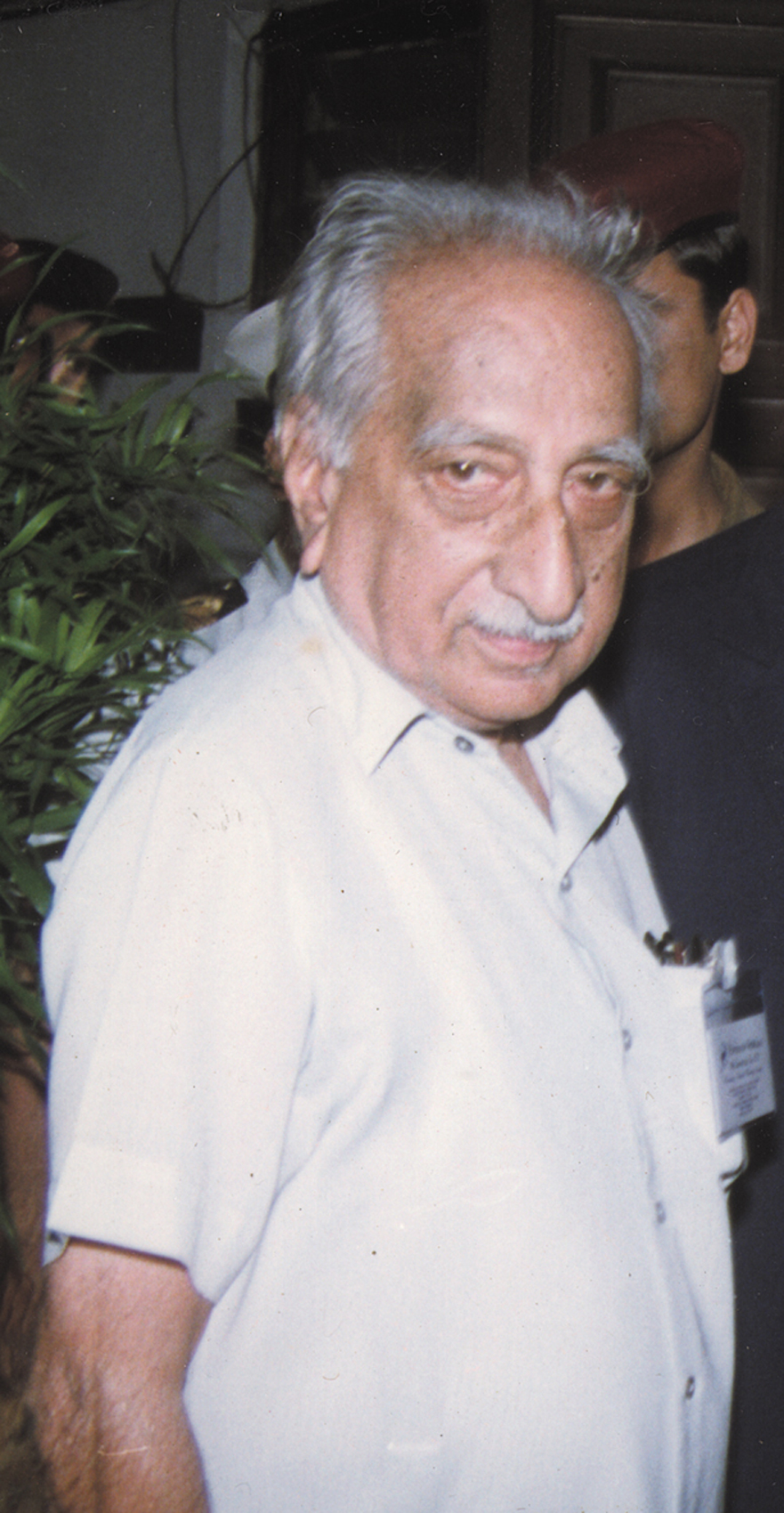

Humayun Abdulali (1914-2001)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 31

No. 6,

June 2011

By Bittu Sahgal

In the pitch of night, in the 1970s, deep in a paddy field in the Western Ghats, an ornithologist who might well be mistaken for Albert Einstein, searches in vain for frogs. Brow furrowed, he realises that Hoplobatrachus tigerina numbers have fallen drastically. Not one to take things lying down, he returns to his headquarters in the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and dashes off several letters to the Indian Board for Wildlife, the Chief Minister and the editors of the most respected national newspapers.

To cut a long story short, after his team made 158 field trips, mostly at night, Humayun Abdulali managed to roll out one of the most skillful conservation campaigns that drew support from thousands of people including students, scientists and the members of the BHNS. Using field biology, statistics and sheer tenacity he proved that the export of 4,000 tonnes of frogs’ legs would result in a potential annual increase of 200,000 tonnes of insects and crop-destroying pests. He linked this to the monetary costs and environmental consequences of a rise in pesticide use. The export of frogs’ legs was banned. A landmark victory had been won.

Humayun Abdulali was one of India's finest ornithologists, a prolific writer and an integral part of the Bombay Natural History Society.

Photo Courtesy:BNHS

ACID TONGUE, GOLDEN HEART

“Andamans? You are going to the Andamans? Lucky fellow. I wish I could go but I am too old to make such trips any longer. You must go to Chiriya Tapu. Only Port Blair or are you also going to Narcondam? What about Cinque? But what will you do there? You don't even have a gun and no one can collect anything anymore anyway." This was just prior to the commencement of a BNHS Executive Committee meeting ‘around the long table’ and Humayun was communicative and personable in his own very special, very endearing way. "How are you going? Who is organising everything for you. Why are you going?” The questions came quick and fast. When he learned that I would be scuba diving in places no one ever had before, even Kamorta, he spent 10 minutes asking how long one could stay underwater, whether I could at least bring back some rare corals and then… whether I intended to search for megapodes.

I could see the longing in his demeanour. He loved the remoteness, the uniqueness and the sheer adventure of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. After having made several collection trips, he really knew the archipelago's natural history better than most. He wanted to be the one going. "I hope you make detailed notes. Show me your photographs when you return," he said, just as the other Executive Committee members began to troop into the room and the day's business began.

I can say this now that he is no more (he probably would have shot me had I said it to his face) – I loved Humayun Abdulali. And I have admired him all my life. He lived life on his own terms, preferring truth to political correctness… always! The quintessential ornithologist, he was anything but sentimental about wildlife. He travelled the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent throughout his life with his trusty shotgun by his side and added specimen after specimen to the invaluable Bombay Natural History Society Collections. A prolific writer, the BNHS eventually published over 300 papers, articles, book reviews and notes authored by him. Together with the specimens he collected, these texts serve as an archival natural history foundation for the modern science of conservation biology and natural history.

AS ACTIVIST AS THEY COME

Of course he was much more than a writer, hunter and ornithologist. He was a fighter and a visionary too. He understood something that eludes India’s planners even today; that without protecting habitats, wild species had no future in a land whose human population was expanding exponentially. So he put together the provisions for some of the toughest protective wildlife laws including the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, based significantly on the Bombay Wild Birds and Wild Animals Protection Act, 1951, which he had earlier drafted. This when the ‘establishment’ believed that the loftiest purpose served by wild species was to entertain humans.

Humayun Abdulali stands out in sharp contrast to many modern ‘scientists’ who believe that fighting for the species and habitats they study amounts to ‘activism’ and is best left to ‘activists’. Humayun scoffed at all that. In 1975, a highway was to be built right through the Borivili National Park (now the Sanjay Gandhi National Park or SGNP). Humayun would have none of that. He filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) petition against the highway and had it stopped. But he was pragmatic, not dogmatic. He later personally oversaw the construction of a road built to the highest point in the park because he was convinced this was vital to an Air Force radar installation.

Humayun Abdulali and his more celebrated cousin Sálim Ali (with whom he shared a close but rocky relationship) worked over a lifetime to turn the BNHS from a shikari’s club into a modern scientific institution. They studied decades of amateur pre-Independence observations made by legends such as S. H. Prater, Colonel R.W. Burton, J.W. Best and F.W. Champion. They also catalogued the BNHS’ bird, insect, reptile and mammal collections. And I can personally vouch for the fact that they did this for the sheer joy of being out in the wilds, a joy that sustained them to the end of their days.

I got to know Humayun very well over the two decades I spent with him at the BNHS. This included many one-sided shouting matches (no prizes for guessing who was doing the shouting!) in the course of several BNHS Executive Committee meetings. Once when I seemed particularly quiet he called in the peon, and said, “Bittu saheb ke liye chai lao. Bahut chup ho gaye.”

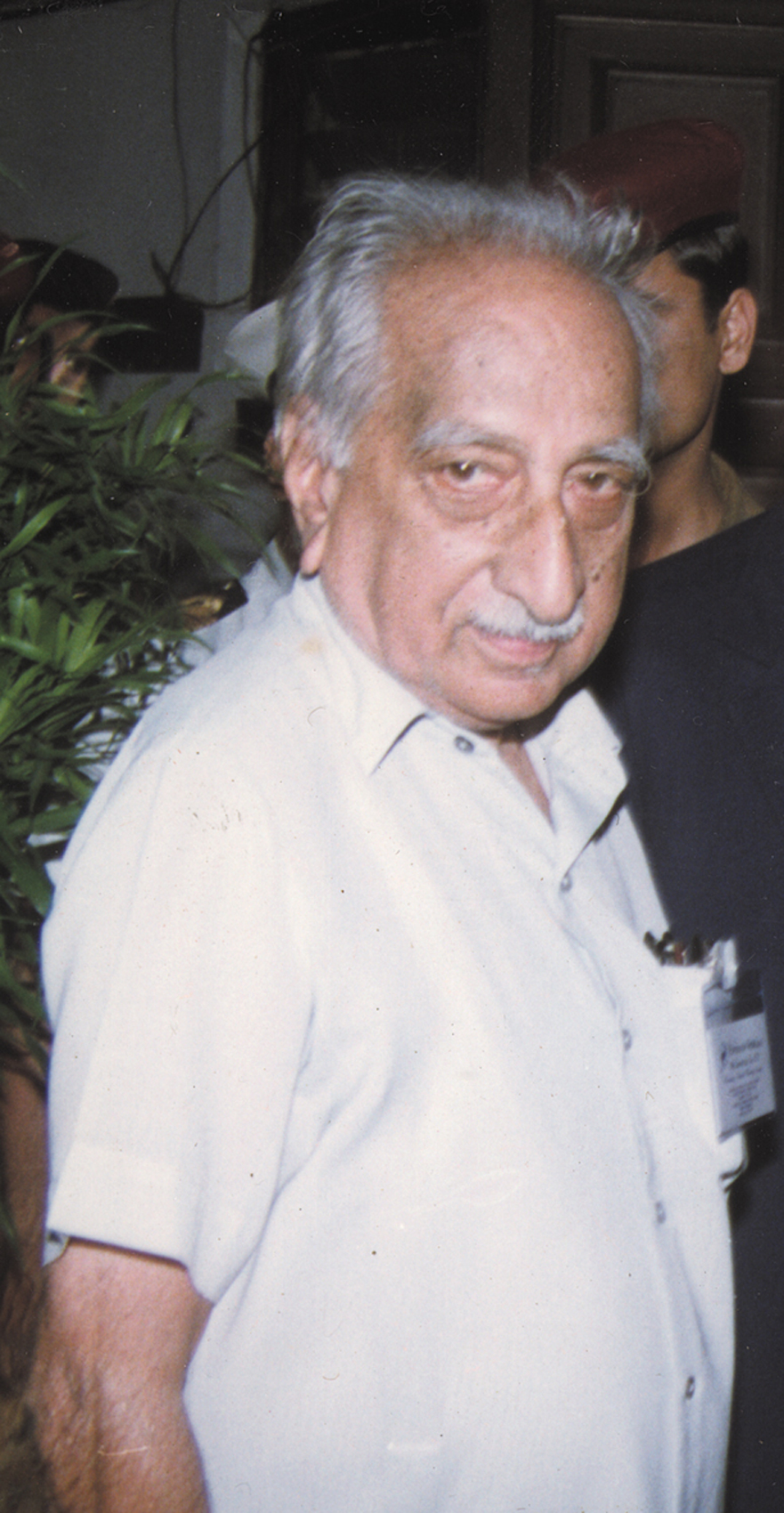

Seen with Indira Gandhi, he was actively involved in the drafting of India's wildlife laws. He had something that is singularly lacking in many of our largest environmental organisations – the gift of the fight.

Photo Courtesy:BNHS

I even went out to SGNP searching for frogs with him a couple of times. But I could never call him a friend (much as I would have liked to). If anything, from the very start he sort of tolerated me. In mid-1981, on the suggestion of J. S. Serrao, I walked up to Humayun unannounced as he was examining a tray of stuffed, brown birds in the Collection Room of the BNHS.

“I am thinking of starting a wildlife magazine and would like some help from you,” I said to him. To which, after a very short pause he replied, "What do you know about wildlife? What makes you think you can run a wildlife magazine? You will probably fill it with rubbish." And, as an afterthought, "Though I suppose if you hang around here long enough you might learn something." That was so typical of the good-natured, acerbic, twinkle-in-the-eye responses I became accustomed to from Humayun Abdulali down the years.

The building in which we sat, Hornbill House, became part of the heritage of the BNHS thanks to Humayun. It was on his persistent urging that the Trustees of the Prince of Wales Museum agreed to rent the premises to the BNHS for the royal sum of Rs. 1/- per annum, primarily to house the Society's bird and animal collections. In the event, Humayun took a long time to warm to me, which he did on and off for decades to the day he died in 2001. But he never once agreed to write for Sanctuary though I must have asked him to scores of times. "Most of what you publish is fiction. Where are the references? Who peer reviews the rubbish you publish?" He never forgot and never forgave me for spelling mistakes of scientific names that he discovered in Sanctuary’s inaugural issue. But he would pour over issues from time to time, often sitting me down right next to him to answer his questions – where, who, when… never “what”.

I was there at the mosque when the prayers were read over his lifeless body. In him was a fire that I continue to feed from even now when I have to fight hard, lonely and thankless conservation battles.

Something very spirited left the BNHS when Humayun Abdulali died.

A CHRONOLOGY

1914: Born in Kobe, Japan.

1929: Family returns to Bombay.

1931: Joins the BNHS.

1942: Elected to the BNHS Executive Committee.

1946: Marries Rafia Tyabji.

1949: Elected Jt. Honourary Secretary, BNHS with Sálim Ali.

1953: The Bombay Wild Birds and Wild Animals Protection Act, 1951 that he played a key role in drafting comes into effect.

1954-62: Honourary Secretary, BNHS.

1963-77: Made eight trips to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

1965: BNHS moves into Hornbill House, the premises he organised for the Society from the Prince of Wales museum.

1968-1996: Publishes the Catalogue of Birds in 37 parts in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society.

1975: Files petition in the Bombay High Court and wins a stay on the construction of a road that would have destroyed the Borivili (now Sanjay Gandhi) National Park.

1985: Publication on the Export of Frog Legs from India, which led to a ban on the export.

1987: Appointed Vice President, BNHS.

1993: Appointed Emeritus Scientist.

2001: Passes away in Mumbai.