Exotic Aliens: The Lion And Cheetah In India

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 33

No. 4,

April 2013

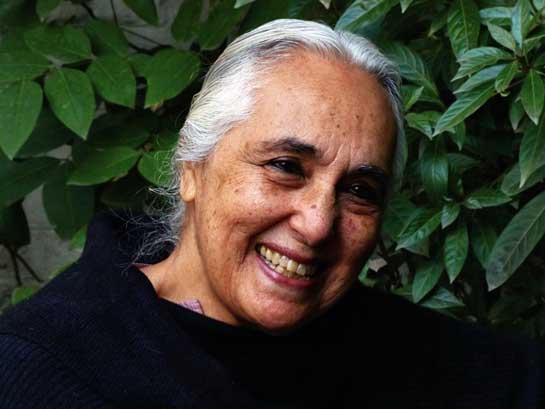

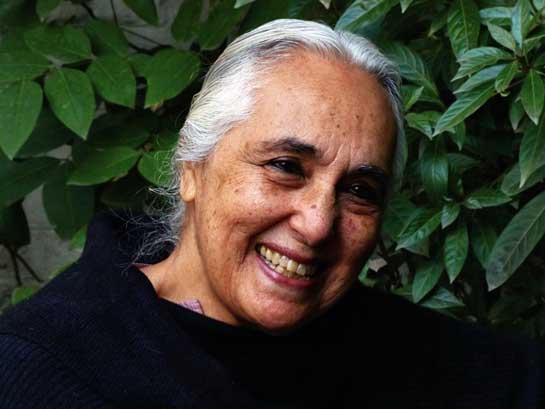

A Book Review by Bittu Sahgal

Exotic Aliens: The Lion and Cheetah in India

By Valmik Thapar, Romila Thapar and Yusuf Ansari

Published by Aleph Book Company

Hardcover, 304 pages, Price: Rs. 595/-

My first reaction was “Impossible!" The very suggestion that lions and cheetahs might have been imported into India by humans relatively recently, and had not trotted across the land bridge from North Africa, through Iran and into India, was, to put it mildly, preposterous.

I had heard about the work on this book from Valmik Thapar for months, and like any puzzle, the hypothesis was engaging, but sounded, on the face of it, far-fetched. And then I read the book. And re-read it. And the predominant feeling turned from preposterous to: “Could it be? Could it really be?"

This review makes no attempt to pre-judge the case. Nor does it hope to present evidence, clinching or otherwise. What it hopes to do is to stimulate people to read the carefully-constructed, hypnotically-argued manuscript for themselves and come to their own conclusions. It would be a grave error, I might add, to dismiss a book written by three leading thinkers in their disparate fields. Nevertheless, I fully anticipate a whole slew of internecine battles breaking loose over what some have already conveyed to me, is a sacrilegious postulation.

Triggered by curiosity about why there was comparatively so little literature about wild lions and cheetahs in the mountains of books published down the years, Thapar roped in two history experts to examine the historical antecedents of these two charismatic predators.

Romila Thapar, one of India's premier historians writes on 'The Lion: From Pride to Metaphor', and Yusuf Ansari, a Moghul history specialist, penned 'Animals of the Chase' and 'The Shahenshahs Shikar'. Valmik Thapar pulls the rest of the thesis together in a scholarly work that relies both on recorded ancient and modern history and interpretations.

Photo: Valmik Thapar.

The hypothesis is outlined in the prologue itself: “Captain Thomas Williamson, the author of the epic book about India's animals, Oriental Field Sports, says that in the 1780s, while pig-sticking, one was likely to encounter tigers that had strayed into the open, but never lions, or for that matter, cheetahs."

Such observations build a case for both animals to be categorised as exotic aliens: “As I researched into the prehistoric era (eight to 10 thousand years ago) through extraordinary books like Erwin Neumayers Lines on Stone: The Prehistoric Rock Art of India - which reveals the absence of ‘maned felines on rock - as well as through conversations with my aunt, Romila Thapar, and followed the thread of my argument through the pre-Christian, pre-Islamic, Mughal and colonial periods, my conclusion gradually began to coalesce."

As the book proceeds to build its case, we learn that Stephen J. OBrien had written in Tears of the Cheetah: The Genetic Secrets of Our Animal Ancestors that: “‘[The] physical traits in Asian lions are manifestations of extremely severe inbreeding in their very recent past. The evidence for our conclusions was encrypted in their genes… the bottleneck that compromised the Gir lions genetic variation dated back not just one century but three millennia!"

Romila Thapar adds variously: “If there were lions here (in Kutchh), why do they not occur on Indus seals, since the area had many Indus cities and settlements? It would seem that there were no lions in this area during the period of the Harappan cities… it must have been an exotic import all along as there is no gradual decline in the species. I believe that the lion came to India just before or with Alexander's invasion of India around the third or fourth century."

She goes on to piece together all possible facts from million-year-old fossil remains of lions in East Africa, to the Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in France, which depicted wall murals revealing lions, horses, mammoths and rhinoceroses.

Moving to India, Romila Thapar points out that: “Among the animals depicted on seals, on pottery and in three-dimensional forms in the Harappan cities, the lion is conspicuously absent, whereas the tiger, the bull, the rhinoceros and even the mythical unicorn are conspicuously present."

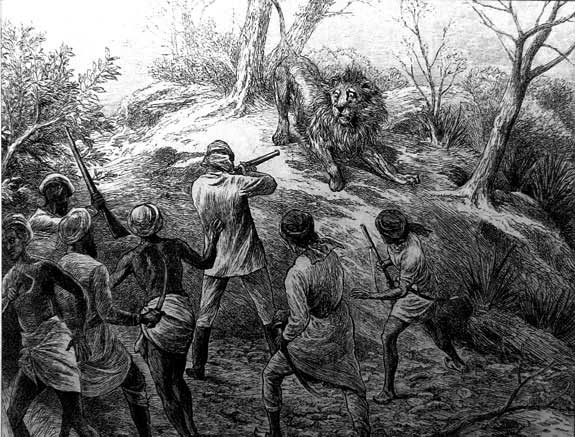

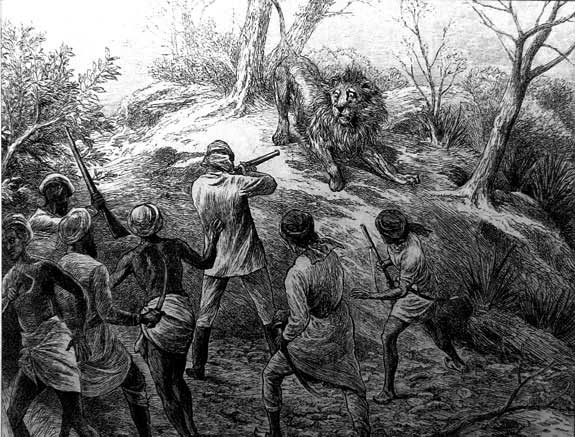

A lion in India ambushed by armed men on foot. Finding a lion in the wild was always a surprise. Photo Courtesy: Private Collection.

A lion in India ambushed by armed men on foot. Finding a lion in the wild was always a surprise. Photo Courtesy: Private Collection.

This is one of the best-referenced books anyone could hope to find on the history of the lion and cheetah in India. At a time when moves are afoot to reintroduce Namibia's cheetah into India, while simultaneously refusing to allow ‘Gujarat's lions to be reintroduced into any other part of India, Valmik Thapar concludes that neither lion nor cheetah was indigenous to India. He adds: “Where the small pride of docile Junagadh lions is concerned, the rulers of present-day Gujarat are no different from the Nawab of Junagadh. The state government regards these animals as the property of the state, just as the nawab did, and has blocked all attempts by other states, like Madhya Pradesh, to propagate the lion."

This is one of the most intriguing books I have read in recent times. It challenges conventional belief. It marshals its thesis brilliantly. It does not take either its own readers or past experts for granted. Every library should have one. Sanctuary will certainly recommend it as compulsory reading for teachers of biology, natural history and human history, and we intend to use the hypothesis to organise academic debates on the subject across India.

Behind Exotic Aliens

To do justice to a book that turns history on its head, it was vital that a touch more than ‘evidence be looked into. This background Q&A between Sanctuary's Editor, Bittu Sahgal and the authors should help Sanctuary readers understand some of the ‘why, where, when, which and who' that triggered this remarkable search into the origins of the lion and the cheetah, which have been presumed indigenous to India for all of recorded history.

VALMIK THAPAR

What would you consider to be ‘clinching evidence' of your thesis that lions and cheetahs were neither indigenous to India, nor a distinctive subspecies?

I do not look at my book as having ‘clinching evidence' since, if it did, I would have established this fact a few years ago. To collect information and then have a very logical and compelling argument that reflects the alien nature of lions and cheetahs in India has been my focus, and I personally believe entirely in the thesis I have spelt out. I think that this book has the maximum amount of information ever on the subject of lions and cheetahs and I am happy to be corrected if someone in the future finds information to the contrary.

In an enormous research endeavour, I discovered that lions were sent to India from Balkh on land routes as early as the sixth century, then by sea from Mozambique in the 17th century and then from many parts of Africa in the 20th century - all to stock the forests of the Maharajas. And with cheetahs, there are endless tributes and gifts during the Mughal period and literally hundreds from Africa early in the 20th century. Both lions and cheetahs, therefore, have African connections in their history in India. I reached my conclusions because the numbers of lion and cheetah were never sufficient for them to have been a distinct species. As I read more and more, my encounter rate with them in the pages of history declined. I believe the lion was bred by Indian kings because it was considered the ‘royal' animal of Planet Earth and was then also hunted in private hunting parks on special occasions, as the Nawab of Junagadh did from late in the 19th century. Cheetahs roamed across India on leashes… and in their thousands. This was an imported royal pet and many escaped during their training and on sport hunts with human handlers. Some lions also escaped from the men who managed them in private parks, which were enormous in size. These escapees created small feral populations. I have gathered in this book as much as I could to reflect on the above.

Are you going to follow through the meticulous work you have done on the history of these ‘exotic' animals, or, having raised the issue, do you intend to leave it to geneticists and academics to debate what you refer to as the lion's khichdi (Hindi for a mashed rice and lentil dish, used as slang for a confused mess) of genes?

I will not pursue my theory further. This must be the task of young scholars across the world, who must probe deeper to discover more. My job was to open up some new and exciting windows of information and I have done that.

A heavily stylised lion rearing over an elephant at the Surya Temple at Konark. Courtesy: Private collection.

A heavily stylised lion rearing over an elephant at the Surya Temple at Konark. Courtesy: Private collection.

Given what Stephen J. O'Brien has to say about the dangerous inbreeding, including malformed sperm, that has taken place in recent times, would you support the revitalisation of lion genes by importing animals into India from North Africa at some point?

I basically have no problems with strengthening the genetic health of lions by North African inputs since so much of this was definitely done in the past.

What is your view on the cheetah reintroduction proposal put forward by the Ministry of Environment and Forests?

I have no problems with the import of Namibian cheetahs since I believe that in the last few hundred years, most of the cheetahs that roamed India on leashes and the few escapees all had largely African origins and so no harm would come from importing any animals today. What should happen at a practical level is a different question... I believe no cheetahs should be imported until we have a new system of wildlife management - otherwise all the cheetahs that are so very fragile in nature will perish in the course of these experiments. Wildlife governance is at such a low that such experiments are doomed to failure.

ROMILA THAPAR

What actually triggered your suspicion that the lion was an import into ancient India?

In the course of studying the ancient world, I was familiar with the depiction of the lion in the sculptures of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia, all of which are earlier than those found in India. Some depictions are symbolic, but those that show the hunting of the lion depict the cat as a powerful, muscular animal that could easily be associated with majesty. The earliest depictions found so far are those of the Ashokan capitals. These appear to be symbolic as they are not of the lion-hunt and hardly represent a powerful predator. Also, their association was initially with royalty and in this, they were following the association of the kingdoms that had existed in West Asia and Africa. This is a contrast to the frequency with which tigers are depicted a couple of millennia earlier on the Harappan seals. This made me suspect that the tiger was the more familiar animal and therefore indigenous, whereas the lion may have entered the scene later.

Are the Ashoka pillars the first-ever depiction of lion art in India when so many countries in the world that never had lions are replete with lion art?

The Ashokan capitals are so far the earliest depiction of lions in a material form in India. Elsewhere lions were either commonly known and the most frequently hunted animal, or they were known as imports, or by reputation and introduced as a decorative motif in various objects, as in parts of Europe in the first millennium B.C. and especially in areas contiguous to or in close contact with Egypt, Mesopotamia and later Persia. In yet other areas such as China and other parts of Southeast Asia, the representation of the lion is later than in India.

Is reliance on history misplaced, given that it is written by the powerful to praise the powerful? How could history have missed the fact that lions and cheetahs were never indigenous to India?

Ancient writers and even historians were not necessarily concerned with whether an animal was indigenous or not. They generally described what they saw or what was told to them. References to the roar of the lion go back to the Rigveda of the late second millennium B.C., but the Rigveda was the text of the particular area of the borderlands in the north-west towards Bactria and of the Punjab. It was not a text referring to all of India. The composers of the hymns or their forefathers could have met the lion or heard about it from its presence in the adjoining Oxus valley. There is one fierce animal that is clearly said to be indigenous to India and is described by Ktesias who lived at the Persian court in the sixth century B.C. This animal is neither a lion, by any stretch of the imagination, nor a cheetah, and most scholars who have studied the text tend to identify it as the tiger.

Even after the lion is referred to together with the tiger and other animals in the forests, or in hunting parks in India, it is curious that it is not depicted as the hunted animal until quite late.

YUSUF ANSARI

In your view, how did the Mughals actually regard lions, and why are scholars so convinced that Akbar had as many as 1,000 cheetahs in his stable? Does this figure sound exaggerated?

The symbol of the lion has been inherited by ruling elites across the world. The case of the Mughals was no different and the lion was a symbol of their Timurid heritage. They attached a degree of mysticism to the lion and tremendous prestige to the killing of this ‘royal' beast. While the lion was a worthy adversary in the field; a royal competitor, the cheetah was perceived to be a fit royal companion. Some accounts credit Akbar with collecting 9,000 cheetahs, which is certainly an exaggeration, even 1,000 cheetahs is a high number given the enormous strain feeding them would have put on the comptroller of the royal household! I don't believe that the imperial stable ever held 1,000 cheetahs at a particular time. If indeed the emperor had a collection of 1,000, these must have included numbers that ranged in the imperial hunting grounds and royal parks as well.

As a history scholar, do you feel that Exotic Aliens might trigger other scholars to focus on the history of animals as a way of filling in gaps or finding fresh clues to events that transpired in bygone days?

That is something we all hope will happen. In the examination of historical documents, the natural history perspective deserves more analysis and study. The focus has been on socio-political, economic and military aspects, generally. Nevertheless, examining the historical evidence available with an aim to better understand what transpired in the history of species, their conservation (or indeed extinction), their behavioural patterns and so on, is both an exciting as well as a necessary requisite. Theories require questioning and examination to determine a degree of certitude about the natural world and there is copious material in the historical record to aid this quest. The Emperor Jehangir, for example, kept detailed records of his observations of animal behaviour and appearances, which form a valuable archive for further research and examination.