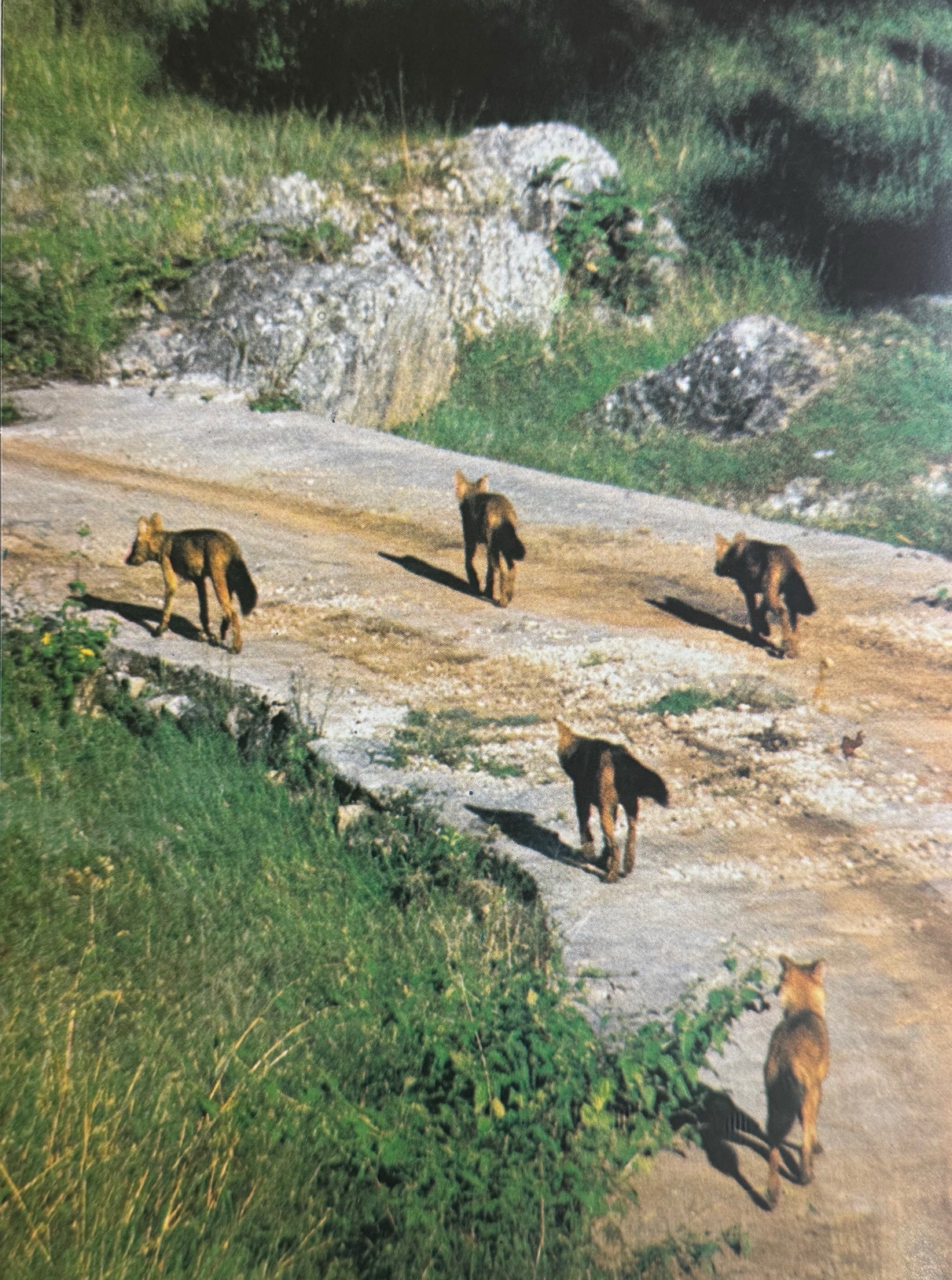

Dhole Dog Of The Indian Jungle

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 4

No. 7,

July 1984

Text and photographs by A.J.T. Johnsingh

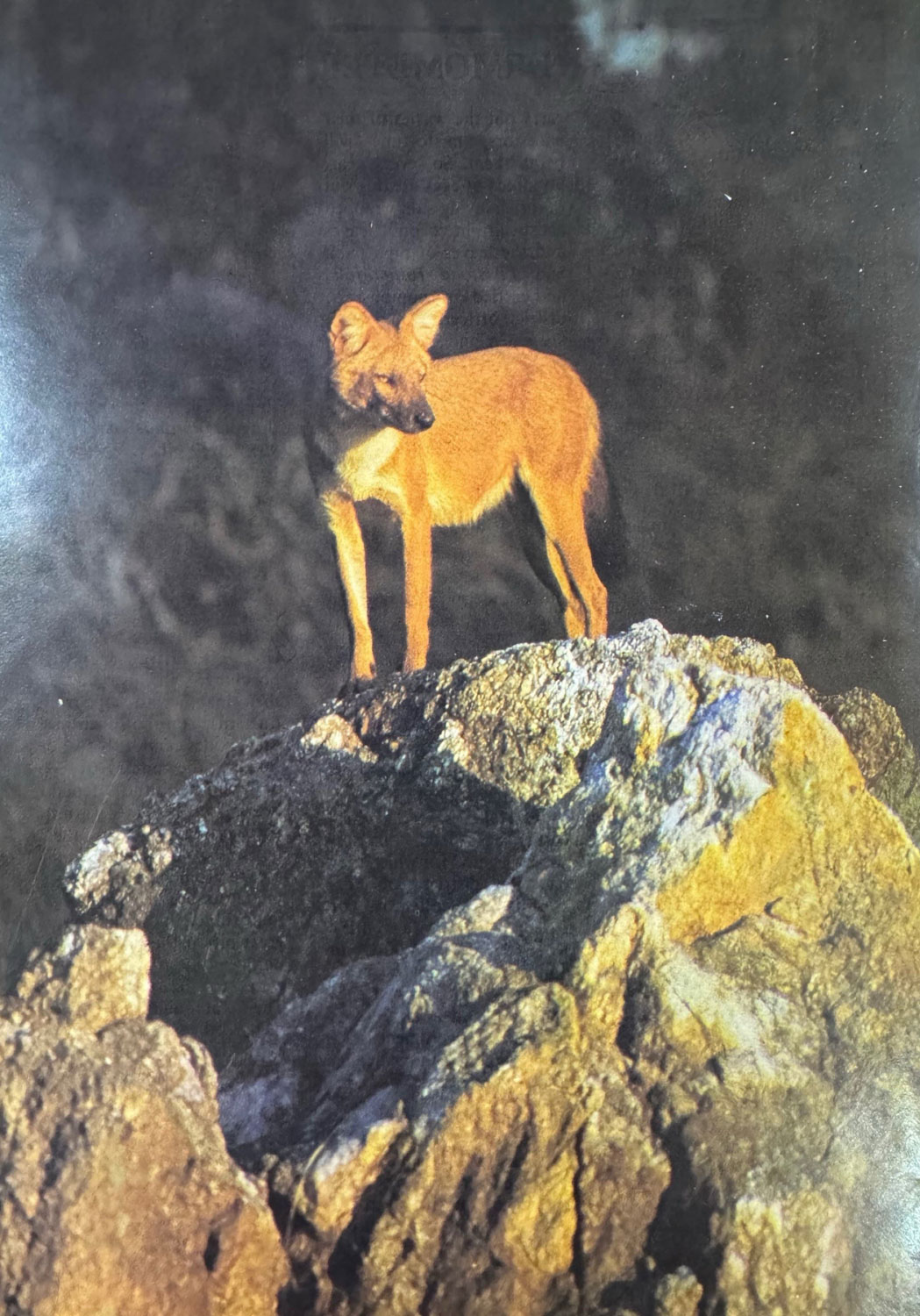

Ka ka khroo... ka ka khroo... A troop of common langurs, on their early morning foraging trip, mistook me, seated eight metres up in a tree, for a leopard and raised an alarm. A dhole bitch shot out from a rock shelter on a near-by hillock. I froze. Although it stood hardly 15 metres away, the dhole failed to notice me as there was no wind to carry my scent. Having verified that no potential danger lurked around the den site, and that the members of the pack had not returned from their hunt, she went back to the den and her new litter of eight pups. I relaxed. My fear stemmed not from any possibility of aggressiveness on the part of the dholes, but from the fact that they, being extremely shy, would move their pups to another den at the first sign of any disturbance. At around 11.00 a.m. the resting langurs again raised an alarm. This time it was a male dhole returning to the den to regurgitate meat for the nursing female and, as I watched, she ran after him through the rocks and dense thickets whining and wagging her tail.

We were a kilometre and a half from Bandipur, the major tourist centre in the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in South India which lies adjacent to the Mudumalai and Wynad Sanctuaries of Tamil Nadu and Kerala respectively. Gently undulating hills covered with dry deciduous forests and teeming with wildlife, are a constant source of delight to both wildlife enthusiasts and tourists. This area has a long history of conservation behind it dating back to the early half of this century, when the Raja of Mysore, a keen sportsman, photographer and naturalist, passed the Game and Forest Preservation Regulation and paved the way for its protection. Today, Bandipur encompasses most of Venugopal Wildlife Park, and covers a rough area of 690 square km. During my two-year study here as a biologist, my major concern was to assess the role of the dhole as a predator and estimate the effect of dhole predation on the deer population. Many Indian forest officials and naturalists continue to blame the dhole for the decreasing deer population. They conveniently forget that poaching is still prevalent in many areas, habitat destruction, in the form of firewood collection, is rampant and that cattle grazing in many of our jungles has increased dramatically. I also wanted to put to rest some of the many myths that surround dhole biology.

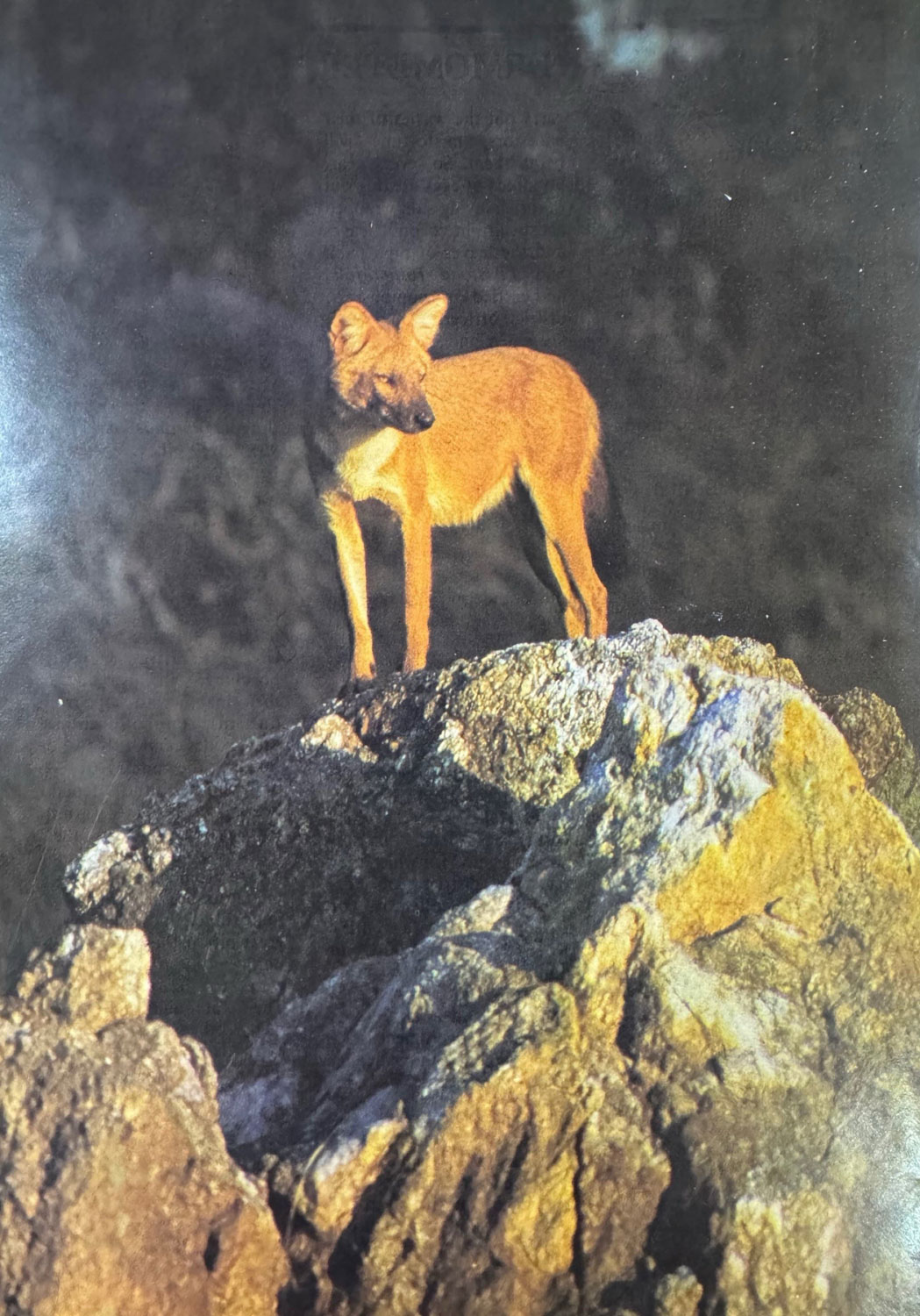

Dholes, or Asiatic wild dogs as they are known, are rust-sand coloured, weigh around 18 kg. and stand approximately 50 cm. at the shoulder. Their length – including a long, black, bushy tail, is about 135 cm. Females are somewhat slighter of build but cannot easily be differentiated from males at a distance. The distribution of dholes extends from Saghalien Amurland and the Atlai mountains (about latitude 500 north) over the whole of continental Asia (east of longitude 700east). They occur on the islands of Sumatra and Java but not in Japan, Sri Lanka or Borneo. Of the nine sub-species recognised by Ellerman and Morrison Scott three sub-species definitely occur in India. They are Cuon alpinus laniger in Kashmir and Lhasa, Cuon alpinus primaevus in Kumaon, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan and Cuon alpinus dukhunensis south of the Ganges. The dholes found in the Namdapha area in Arunachal Pradesh could well be the Cuon alpinus adjustus from North Burma.

Scent is an important means of communication amongst dholes.

Despite numerous first-hand accounts, when compared to other pack hunting canids such as the wolf and the African wild dog, the dhole remains little studied and much misunderstood. Even now it carries a stigma with it and until 12 years ago a bounty on its head placed its worth at twenty rupees.

The field work I was doing, with support from the World Wildlife Fund and the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, England, was the first long-term study of the dhole. However, the facilities and equipment I had, when compared to those normally available to wildlife biologists from the West, were highly inadequate.

In fact all canines have a scent gland on the upper basal half of the tail. The jackal Canis aureus is the scavenger member of the dog family usually to be found hunting singly or in pairs.

I had neither a vehicle nor radio-telemetry equipment at my disposal. Only two tribals assisted me in locating the dholes and searching for the kills of other predators -- the leopard and the tiger. Another major limitation was that elephants prevented me from working at night, at dawn and at dusk. So, early in the morning and evening, the two tribals and I, used to hike in different directions in an attempt to locate our subjects, with the help of the alarm calls of prey such as chital, sambar, langur and peafowl. We systematically combed the scrub on foot and often located the kills by the raucous calls of the ever-present jungle crows. Over a period of time, we assessed the abundance of such cover-seeking animals as sambar, barking deer and wild pig and were thus able to understand more about the predator-prey balance in the jungle. Life in the jungle, inevitably had its moments of danger -- especially when in the excitement of following dholes, caution sometimes got thrown to the winds. Once in a dense lantana scrub, I almost walked into a sleeping cow elephant which I mistook for dead! To verify the cow's condition I gently threw some hard earth at her only to have her come charging out at me with her calf in tow. Another cow elephant once opted to chase the forest department van as I descended from it and in the melee the driver drove off leaving me to deal with the cow! Only my familiarity with the area helped me escape as I jumped into a near-by stream-bed. On yet another occasion a tigress with two cubs remonstrated with a terrifying roar as I met them. Less dramatic, but infinitely more irritating, was the problem of ticks in the jungle. After the first few months my body was so completely covered with black itching dots that I looked as if I had had a severe attack of small-pox. All through my stay at Bandipur, much to my dismay, I was unable to develop any kind of antidote to tick-bites! When I started my study in August 1976, it took me six full days to just sight my study pack. During those six days I had walked nearly 90 km. through Bandipur, criss-crossing my study area of 32 square km. and finding nothing more than the tracks of five dholes which had unsuccessfully chased a sambar across a shallow pool. With so little progress, desperation began to set in. My colleagues and the local officials suggested that I had perhaps chosen the wrong animal for my Ph.D! On the morning of the seventh day however, the tension was relieved when one of my field assistants brought in the lower jaw of a chital stag which had been killed by dholes. That drizzly evening while I was routinely observing sambar from a tree, I suddenly spied my pack in action, 15 dholes in all, killing a chital doe which they had cornered after a chase. The long and slow process of gathering data had begun.

One of the benefits of pack life for dholes is the efficiency with which kills are consumed.

To a casual observer almost all dholes look alike. Nevertheless, there are variations in the rusty, sand-coloured fur and black bushy tail which makes the identification of a few individuals possible. `Bent Ear' was one such individual I grew to recognise. Old, with a loose hanging scrotum, a bent right pinna (which gave him his name) and a bend in his tail, he appeared to be the leader of the pack. In typical dog-fashion he occasionally showed his dominance by raising one hind leg and urinating onto tree trunks in the presence of the other dholes. However, he never bullied them. On the contrary, the pack members often greeted him, sometimes even to the extent of crawling under his belly, forcing him to jump aside. `Bent Ear' was extremely fond of pups and when the pack had made only a small kill the pups would run to him pestering him to regurgitate some extra meat. Like the African wild dog, `Bent Ear' would oblige them even six or seven hours after he had eaten. I soon developed a strange affection for this aged hunter who flitted freely through the forest. He led a daring life. Alone and unafraid, he slipped easily through the thickets, which I entered with hesitation and, occasionally, fear. When he suddenly disappeared in April 1978, I felt a pang of sadness which stayed with me for a long time. I had lost a friend.

From the study certain interesting results emerged. I was surprised in the first year when, in the month of November, just prior to the birth of eight pups the pack of 15 was suddenly reduced to seven or eight animals. (Though there were three females only one gave birth to pups.) Later I realised that emigration of a part of the pack before the arrival of the pups, and also breeding by only one female, might be the major means of regulating pack size. Also, at no time were two packs seen operating in the same area; which suggested that dholes may be territorial. The focal area of my study pack was nearly twenty square km., an area I grew to know better each time I traversed it on foot.

Many people blame the dhole for the decrease in the Bandipur deer population but they forget that a combination of poaching, habitat destruction and cattle grazing have all contributed to this decline.

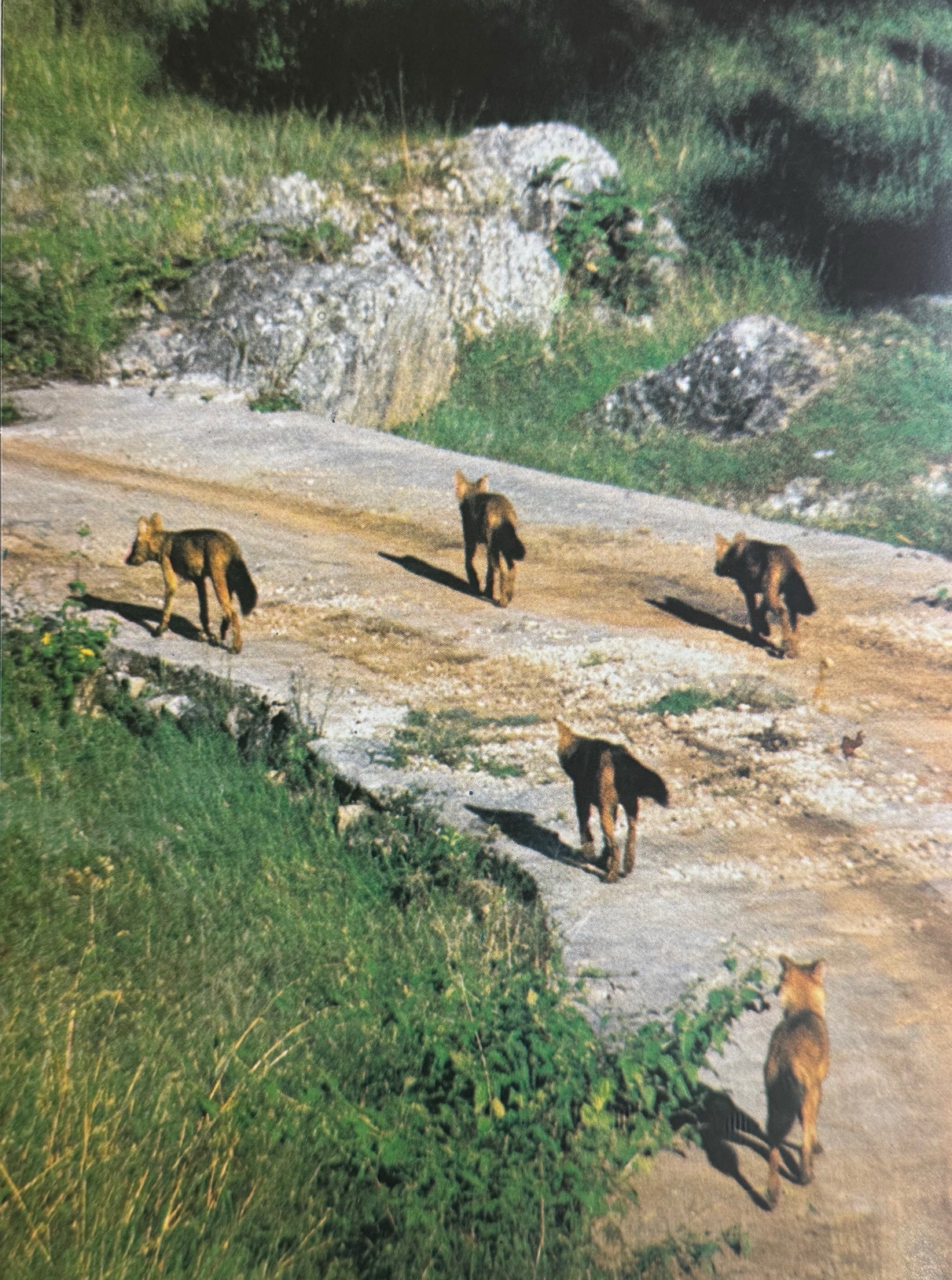

The pups remained in the den until they were 70-80 days old and during this time did not visit the near-by water-holes. Pack life manifested itself not only in group hunting but also by the participation of all the pace members in feeding the pups. It was a thrill to watch Nature's miraculous learning process at work as the seven-to-eight-month-old pups first began to take an active part in hunting chital and sambar. The dholes' hunting strategies displayed perfect team-work. There seemed to be two basic manoeuvres to flush and kill prey -- one by moving through the scrub in an extended line formation and the other by having some of the pack remain on the periphery of the scrub to intercept the fleeing prey disturbed by other members of the pack.

The pack cared for the pups even after they had left the den and until they were four-to five-months-old, the adults treated them with special concern and solicitude. They would hunt either very early in the morning or late in the evening to avoid both the presence of man and the heat of the day. The pups were left in hiding during these hunts and the absence of a couple of adults in the hunting pack even suggested that some animals may have stayed behind to guard them. Eventually, even when the pups started following the pack on hunts, young stragglers were escorted by one or two adults. Pups were permitted to monopolise small kills like chital and, when food was insufficient, the adults who had eaten earlier even regurgitated meat for them. At larger kills like sambar which are over twice as large as chital, pups and adults often ate together. When they were seven months old however, and the food was inadequate, adults began to be reluctant to regurgitate food despite the fact that the pups were hungry. Often however, the young ones chased them and appealingly nibbled the corners of their mouths until the elders obliged.

The elephants at Bandipur prevented the author from working at night, at dawn and at dusk.

During my many months in Bandipur I made many observations which clearly showed that dholes seldom hunt by relay. During the rush stage of the hunt, dholes are faster than their prey and with their speed and team-work most chases do not last long. Of the 48 chases I witnessed, 44 ended within 500 metres and only twice did the chase go beyond 500 metres. This data disproves the popular theory that dholes chase their prey over great distances in relays thus tiring the quarry but not the pack.

Dholes are not always the super efficient killers they are made out to be. One dry summer evening, while making my way back to Bandipur, a sambar doe trotted across my path followed by a dhole, trailing 70 to 80 metres behind. The dhole, however, appeared to have lost the direction of its prey's movements. I then heard other members of the pack, which had obviously lost sight of both prey and pack member, trying to renew contact with their leader, by their high-pitched whistling calls. The next day, with the help of some tribals, I combed the area thoroughly but found no kill. Neither did I see any jungle crows, which are good indicators of a kill. All this told me that the hunt had been a failure.

Dholes hunt either very early in the morning or late in the evening to avoid meeting man and also to escape the heat of the day.

One March evening my attention was abruptly drawn to a silent struggle between a chital stag -- with well-developed, hard antlers -- and a group of seven dholes. Two or three dholes were biting and hanging on to the rump of the stag, thereby rendering it completely immobile, while the others worried the flanks. The stag was trying to fight off the dholes by swinging its great antlers which never once, however, came in contact with the dogs. Throughout the struggle the dholes remained silent although the deer vocalised its agony three times. Suddenly one dhole caught the snout of the stag and pulled it forward while those at the rump continued to bite and pull it backwards. Eventually, the helpless stag, was dragged down and the dholes started eating it even before it had died! Although predation is as much a biological process as grazing is, such incidents are often gory and repugnant. However, in defence of the dhole, I recount the opinion of Michael Fox, with whom I first studied this animal. He felt that since dholes lack the killing bite of the large cats, they can best kill prey, larger than themselves, by biting off chunks of meat. An animal thus weakened obviously became easier to overcome as massive blood loss and shock progressively lowered its resistance. Close examination of fresh kills clearly showed that dholes are particular about holding on to the nose of stags sporting hard antlers probably to prevent themselves from being struck by these potential weapons.

An amazing fact about the dhole is its ability to consume large quantities of meat. A pack of 15 could easily eat a yearling sambar male of about 90-100 kg., each animal consuming about five kg. After such a meal the dholes do not hunt for quite some time (even a two kg. morning meal would keep the animals away from another hunt till the next day). This capacity to gorge themselves is believed to enable them to live without food for a few days although this is yet to be verified in the field. One of the benefits of pack life is the efficiency with which kills are eaten. Even the bones and skin of a young deer are swallowed and when larger kills are made, the dholes may even come back to scavenge on the dry stiff skin. Such scavenging makes it possible for the dhole to appropriate kills of leopards and tigers and on many occasions leopards have actually lost their kills to dholes. This stealing of kills from other animals, however, may be dangerous; and I once saw a dhole pup, nearly six months old, killed and partly eaten by a leopard in Bandipur -- the potential robber had become the prey.

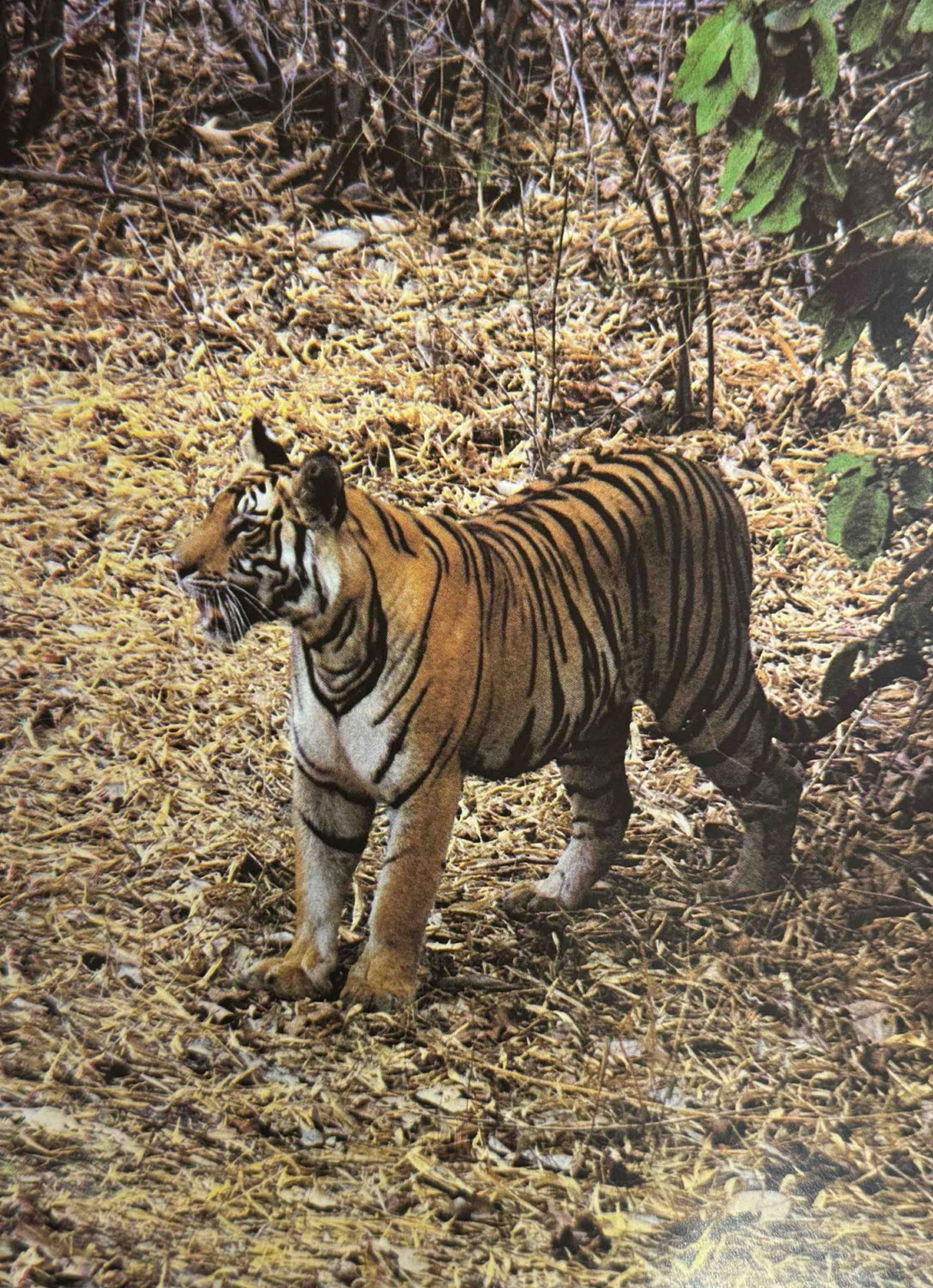

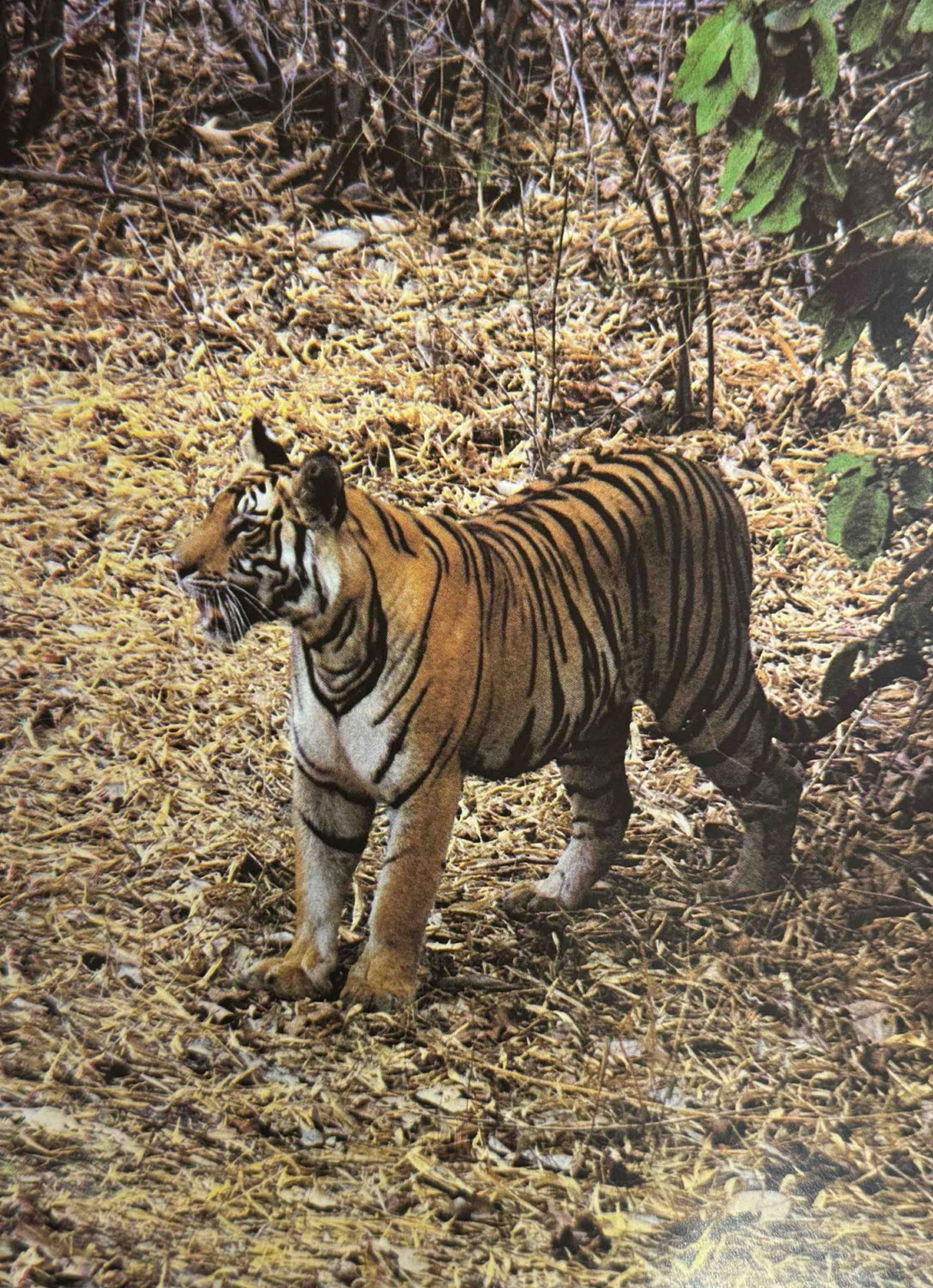

In Bandipur there was no evidence, however, of either tigers or leopards regularly competing with dholes over a kill. The ability of each to kill prey of different ages, sex and size enables dholes and the larger predators to co-exist. Over 42 per cent of the 19 tiger kills I counted, for instance, were above 100 kg., whereas out of 302 dhole kills only one per cent were of that weight. The obvious deduction is that the tiger prefers larger food items. Dholes also seem to show a preference for male sambar. Out of 10 dhole kills, seven were males. Tigers on the other hand seem to prefer attacking female sambar (this, however, was based on a small sample and before any real conclusions are drawn much more research is necessary). Young chital, being alert and agile, often escaped from dholes. They, however, seemed to fall easy prey to leopards which hunt by stealth and surprise. Another factor that seems to reduce hunting conflicts between the dogs and the great cats, is the fact that dholes are diurnal and prefer relatively open areas, while tigers and leopards are nocturnal and use dense cover from which to launch their attacks.

The dhole's whistle call (which can be imitated by blowing into a medium-bore empty rifle cartridge) would fascinate anyone who heard it in the jungle. How the dhole produces this sound is a complete mystery. Dholes separated from the rest of their pack whistle to reassemble after an unsuccessful hunt and even lone dholes may whistle occasionally to discover the position of other pack members. I have never, however, observed dholes whistling to maintain the cohesiveness of their pack while a hunt was in progress. Sounds play an important role in the lives of dholes and I found that they could be alerted, not only by imitating their whistle, but also by blowing air out through a leaf thus producing a shrill note similar to the distress call of a fawn.

The dholes' hunting strategies display perfect teamwork. They seem to operate by two basic manoeuvres -- one is by moving through the scrub in an extended line formation and the other by having some members of the pack remain on the periphery of the scrub to intercept the fleeing prey.

Of the many unusual dhole behaviour patterns I observed, one was the use of communal latrines. One particularly eventful evening (I had the good fortune to spot both a leopard and a magnificent tusker that day) as I sat atop a tree close to a well-frequented jungle trail, I spotted two dholes which came out of the jungle followed by 14 more and they all lay at the crossing nudging one another and whining. Nine of them defecated at the crossing before they left the place in single file led by `Bent Ear'. This feature of a communal latrine is peculiar to dholes and anyone walking in a jungle, frequented by dholes, will often come across their communal latrines on roads and animal trail crossings. This habit is not seen in the African wild dog and rarely in wolves; and may well be a display, warning neighbouring packs of the presence of the resident pack. Further, the scats probably aid pack members in tracking their fellow members as also in determining whether an area has been hunted in recently.

During the months of December 1976 and January 1977 I regularly watched `my' pack caring for the pups and their mother. As February progressed the pups became stronger and their speed and agility increased. I thoroughly enjoyed stalking the playful pups and would freeze for minutes when I felt that the adults had become aware of me. On such occasions I would silently climb a tree to allow the wind to disperse my scent.

Until the evening of February 14, 1977, the dry weather held out and the sound of the pups running and playing over the dry leaves could be heard even 200 metres away. A good evening shower three days later made the leaves soft and damp and the next day I was able to crawl as close as 30 metres to the den to observe the pups, both in the morning and evening, without alerting the sharp-eared pack.

That evening, however, half an hour after my first `visit' to the den, instead of the anticipated squeaks and whines of the pups and the soft growls of the adults, I was confronted with an ominous silence. I knew that the time had come for the pups to leave the den but such a sudden departure took me by surprise. In spite of the many common langurs, chital and grey jungle fowl feeding around the den site, I felt quite alone, almost abandoned in fact. Some alarm calls in the distance, however, suggested that the pack had not gone too far (their home range was around 40 square km.) and I was subsequently able to observe them several times before my departure.

In Bandipur there is no evidence of the tiger coming into conflict with the dhole over a kill. Unlike the dhole, tigers are nocturnal hunters and seem to prefer larger game.

Now, when I think back, I realise that my study, when compared to the magnitude of work done by others on pack-hunting canids, has merely scratched the surface of the vast potential information on dhole biology. Many questions still remain unanswered. Why do dhole populations periodically decline even when there is an adequate supply of prey as in the case of Kanha National Park? What happened to those members of the pack that had emigrated? What was the social status of the emigrant? Does the same dominant female breed every year? What explanation can there be for sambar chasing dholes (I actually saw this happen on more than four occasions) when dholes are capable of killing adult sambar?

The creation of Tiger Reserves has done much to protect the dhole as well, and we can be sure therefore, that like most wild animals, dholes too will do well if left undisturbed. However, a long-term study of two or three neighbouring packs, with each individual tagged and some radio-collared, is necessary to learn more about the social and physical characteristics of these, one of the world's most efficient predators. When I conducted my study, neither was I conversant with modern techniques like radio telemetry nor did Park `rules' permit such vitally necessary know-how. Still I hope that the day for such research, which alone can answer the questions raised above, is not far off in India.