Bhigwan: The Story Of A Wetland

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 6,

June 2023

By Dr. Erach Bharucha

The Early Days

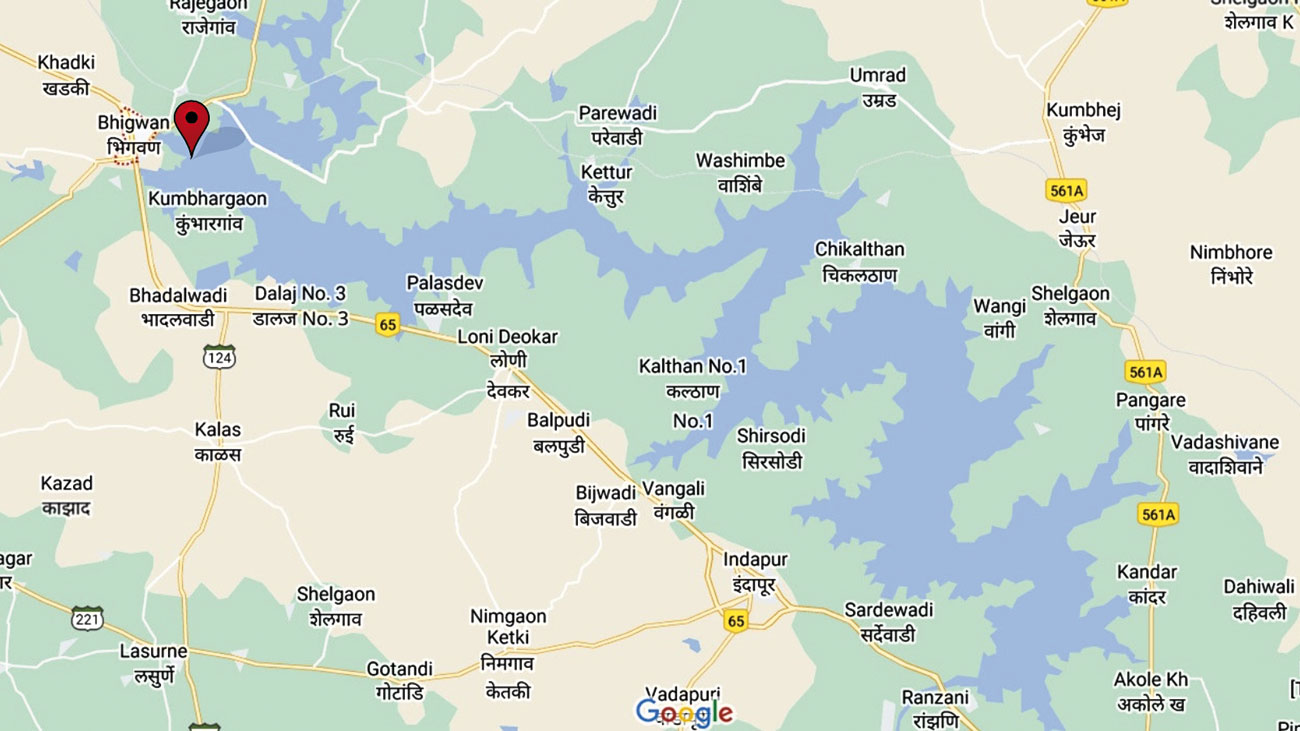

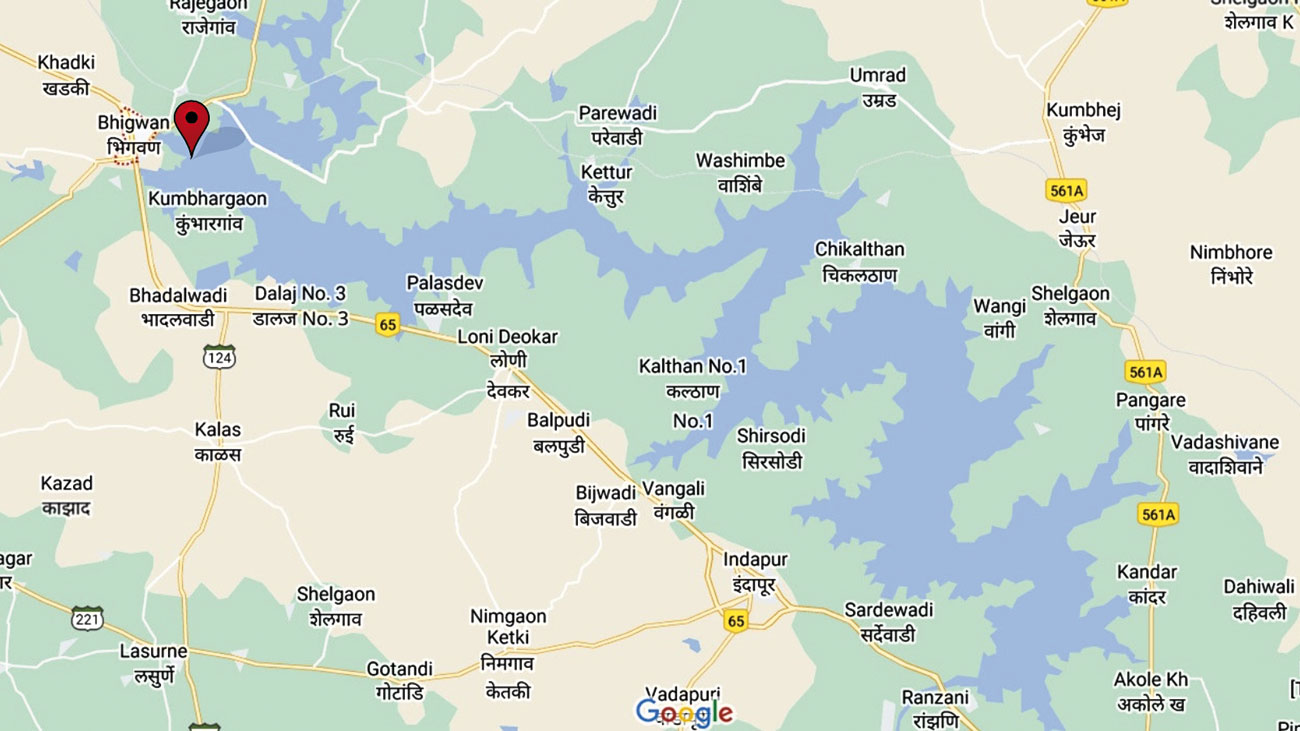

In the mid-1980s, a surgeon colleague driving from Pune to Solapur in Maharashtra called me about a sighting of a flock of ‘pink birds’ at the edge of the spreading backwaters of the newly completed dam at Ujani on the Bhima river. My sceptical guess was flamingos, because they had not been seen in this area. We travelled together the following weekend to the village of Bhigwan, and sure enough, at the edge of the waterbody was a flock of around 50 Greater Flamingos Phoenicopterus roseus. These brilliantly-plumaged birds are filter feeders, and get their colour from carotenoid pigments in algae and the zooplankton and small aquatic animals they consume from the mudbanks at the fringe of the water. Watching them croaking and feeding, I was hooked! The flamingo, after all, belongs to the oldest bird groups alive today, and here they were, barely three hours from the bustle of the city. The Bhigwan wetland at Kumbhargaon became a regular Sunday visit for the doctor and I to go ‘birdwatching’. Subsequent winters brought with them spectacular congregations of migrant waterfowl – ducks, waders, ibis, and storks gathered as the drawdown of water left large tracts of open mudbanks and aquatic grasses, where the birds could feed undisturbed. I realised that the Ujani dam had given birth to a new ecosystem for migratory birds, a welcome (wholly unintended) effect of a human-made structure.

As a committee member of the fledgling Pune branch of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), I decided to conduct an ecological monitoring project and regular winter waterfowl counts in the backwaters of Ujani dam, 108 km. from Pune. The small grant was just enough to fund Pradyumna Gogte, an M.Sc. Environment student of Pune University, allowing him to visit the wetland once or twice a month, conduct bird counts, and analyse the water quality.

A flock of Greater Flamingos feeds in the shallow waters of Bhigwan, Pune. The largest and most widespread species of flamingo, Greater Flamingos are distributed in Africa, the Indian subcontinent and parts of the Middle East and southern Europe. A 2021 study brought up a surprising find as scientists discovered that the closest living relatives of flamingos are grebes – a species of diving piscivore birds. Photo: Surendra Walke/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

Community Participation

My regular birdwatching trips continued, leading to fascinating new finds. One evening I identified a large number of juvenile Gull-billed Terns Gelochelidon nilotica on Pune’s Mula Mutha river. They had to have a breeding colony nearby! Pradyumna Gogte, my field scientist, located the colony in the backwaters at Bhigwan, scattered on the emerging mudbank islands, where the terns, pratincoles and plovers were all nesting after the monsoons ended year after year. I interacted with local fisherfolk and convinced them to protect the islands and avoid using it for drying fish nets. They complied – the Pune doctor was considered a useful visitor to the Kumbhargaon and Dalaj villages, as he was happy to treat local patients at Sassoon General Hospital, and even operated on them on occasion. Several local village folk became great friends of ours. The school students were excited and gathered around the odd little Triumph Herald car that bumped over the cart track on weekends. They were given the task of making birds fly off if urban shikaris with guns attempted to shoot water birds, a job they fulfilled with glee. They sometimes confused large telephoto lenses with guns and chased the birds away just as I had teed up the perfect photograph, but it was a small albeit frustrating price to pay for the birds’ protection.

‘Bird curiosity’ was growing among a few citizens in Pune. WWF conducted visits on Sundays. I organised urban school visits. The arrival of the ‘agnipankh’ (the Marathi term for flamingos) was heralded in the local Pune and Solapur press. A local tea shop owner guided birdwatchers to the most likely spot to see the flamingos – and the partially submerged old Pune-Solapur highway became a birdwatchers’ vantage point.

Local villagers continue to practice traditional fishing methods but also increasingly rent out their boats to birdwatchers flocking to Bhigwan for a glimpse of flamingos, storks, herons, gulls, waders and other water birds. Photo: Dr. Erach Bharucha.

One Sunday I realised that there was a succession of changes in the wetland habitat. The UGC had a centre in Pune University that was working on making educational films. The team agreed to make a documentary on the ‘Changing Nature of the Wetland’. The video was quite a hit with college students in those days, with underwater images that were made by placing the camera in a fish tank and lowering it into the lake so the aquatic system could be depicted, from algae to macrophytes and fauna that lived underwater. The video outgrew itself, from a flamingo story to a wetland story.

Conservation Efforts

One day I observed pairs of flamingos interacting with each other, croaking, spreading their scarlet wings and raising their powder-puff-like dorsal feathers. I showed pictures of this display to Dr. Sálim Ali, my guru on such matters. He viewed the slides and asked if I had been to the Great Rann. “These birds are forming pairs,” he said. I asked if they would nest in Bhigwan and he said that was unlikely to happen. “But you never know,” he quipped. He told me that in Camargue in France, a nesting colony of flamingos had been disturbed and had stopped breeding. He had heard that the ornithologists made artificial nests and this led to re-established breeding the next season. I tried to convince my Forest Department friend K.A. Shaikh to make artificial nests at Bhigwan. He laughed and called it a crazy idea – but when I casually said this was

Dr. Sálim Ali’s suggestion, he promptly agreed. Some school kids helped in the activity. The local farmers and fisherfolk thought the surgeon/birdwatcher had lost it. The flamingos investigated the nests, but decided not to use them. We made clay flamingo-sized eggs from a local potter and laid them in the nests. The flamingos were still not convinced, but a confused juvenile did sit regularly on one of the nests. The rains finally washed the artificial nests away.

I managed to induce the Government of Maharashtra to set up a State Wetland Board, and I presented the Bhigwan study to the board. However, creating a Protected Area there was ruled out as the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) had plans for the site. Vijay Pranjapye and I took B.G Deshmukh, the then Chief Secretary of Maharashtra, to see the flamingos, and notify a Protected Area. This did not work either. The site remains unprotected to this day. A study by Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON) on inland wetlands of India was undertaken for Maharashtra by the Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Environment Education and Research (BVIEER). Bhigwan was rated the best wetland in the state. The study also identified Jaikwadi and Nandur as good sites, and these were given sanctuary status.

In face of the growing threats from insensitive tourists, there is a great need to develop a sustainable tourism strategy for Bhigwan that generates income for locals and does not exclude them from wetland access. Photo: Dr. Erach Bharucha.

Publicity through the press gave rise to an increasing number of flamingo-focused Sunday visitors. Some of the local fisherfolk began taking people for boat rides. Over the last two decades, Pune has seen a great rise in the number of bird photographers with giant telephoto lenses descending on the backwaters where the aquatic avifauna winter in their favoured feeding zones. A local school boy, Sandip Nagare became an ardent bird enthusiast. He began using his fishing boat to take visitors birdwatching regularly. The two Nagare brothers, trained other local boys as guides. The team at Kumbhargaon became serious ‘citizen scientists’ all on their own. They now identify all the birds by scientific and local Marathi names. They identified the habitat mosaic types certain birds favoured and observed the breeding behaviour of all the local birds.

Encouraged by NGOs, people made regular visits to the wetland for wildlife-related nature studies. The growing number of tourists and regular visits by college students from BVIEER encouraged the Nagare family to develop a small homestay facility. The family supplied a fabulous local meal and freshly-caught fish. Students would return from the wetland field study, ecstatic, and with a heightened sensitivity to preserving wetlands and their wildlife. The Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) conducts a study on migratory avifauna through a formal bird-ringing programme annually.

The Pros And Cons Of Tourism

Tourism through the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC) is growing rapidly at Bhigwan, and is expanding beyond the carrying capacity of the wetland. On weekends, birdwatchers wish to get closer to the flamingos in the fishing boats to see the spectacular birds and make them fly and show off their scarlet wings. Cameras click and whirr as the birds take flight. Tourists frequently ask to see the nesting islands, which causes a chaotic disturbance to the terns, pratincoles and Black-winged Stilts that have an active nesting colony on the island. The parent birds are frantic as the nests have eggs, chicks and juveniles. These ground nesters camouflage their nests and eggs so perfectly that a single false step can crush them. Trampling of nests by cattle and humans has been a major cause of nest mortality of River Terns, pratincoles and Black-winged Stilts at Bhigwan.

Getting up close to the thousands of winter migrants makes the flocks fly to an alternate feeding zone. As tourism grows further, this will drive birds away from one site to another repeatedly and disturb their feeding behaviour. Migrant birds require continuous feeding to build energy reserves before their long and arduous flight across the high passes of the Himalaya to their summer nesting ground in the tundra. Disturbing feeding at Bhigwan may well be a cause of trans-Himalayan mortality. In face of the growing threats from insensitive tourists, there is a great need to develop a sustainable tourism strategy. Besides, flamingos have been known to change their migratory patterns suddenly; one of the defining factors is the availability of their highly specialised food. Sustainable ecotourism that benefits local people will be a source of revenue for the local landless farming community, and a supplementary income for fisherfolk.

A Grey Heron pair tends to its downy and rather grumpy-looking chicks. Apart from herons, the author has recorded River Terns, pratincoles and Black-winged Stilts nesting in and around Bhigwan. Photo: Xerxes adrianwalla/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

There are several options that will not cause conflicts with local fisherfolk or the draw-down farmers, which would be sustainable and satisfy the needs of long-term biodiversity conservation and sustainable local development. Creating a sustainable plan of action as suggested in ‘Other Effective (area-based) Conservation Measures’ is suggested under Sustainable Development Goal 15 (Life on Land) for such areas, instead of creating a wildlife sanctuary, which would exclude locals from accessing the wetland. Notifying a conservation reserve would deliver the best conservation success without conflicting with local people’s interests. A third option is to build capacity in the local Biodiversity Management Committee and create a Biodiversity Heritage Site under the Biological Diversity Act, 2002. It is already on the list of Important Bird Areas listed by the BNHS, and is a potential Ramsar Site.

Beyond Flamingos

The Bhigwan wetland is not only a migratory transit zone, hosting migrants but is also a breeding colony for a large number of waders, fish-dependant avifauna such as storks, and ibis that depend on shellfish, snails and crabs, all of which make up a fantastically rich aquatic fresh water ecosystem. In addition to providing a habitat for wild birds, it recharges groundwater stores, and provides drinking water for local people year-round. Farmers around the waterbody should be encouraged to switch from sugarcane, which requires heavy use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, to traditional health food like bajra (pearl millet) and jowar (sorghum) that can be grown with safe, organic fertilisers. This would reduce the chemical run-off during monsoons, which leads to eutrophication and disruption of the food chain. The wetland is a great site for nature orientation for school students and college youth through direct observations of the rich ecosystem.

Oriental Pratincole Glareola maldivarum. Photo: Dr. Erach Bharucha.

The Bhigwan Model

Bhigwan is a super ecotourism model that is a key conservation area for Maharashtra, and a site fit to be a UNESCO Natural World Heritage Site as well as a Cultural Heritage Site, where local fishing techniques are part of local people’s traditions. The Bhigwan model can be emulated in several other sites. Sustainable tourism improves local peoples’ income generation potential, retains their sensitivity and closeness to nature conservation, and furthers the conservation of biological diversity as part of India’s commitment to the Convention on Biological Diversity among the world of nations that believe that conservation of natural resources is the only pathway to a better future for our children.

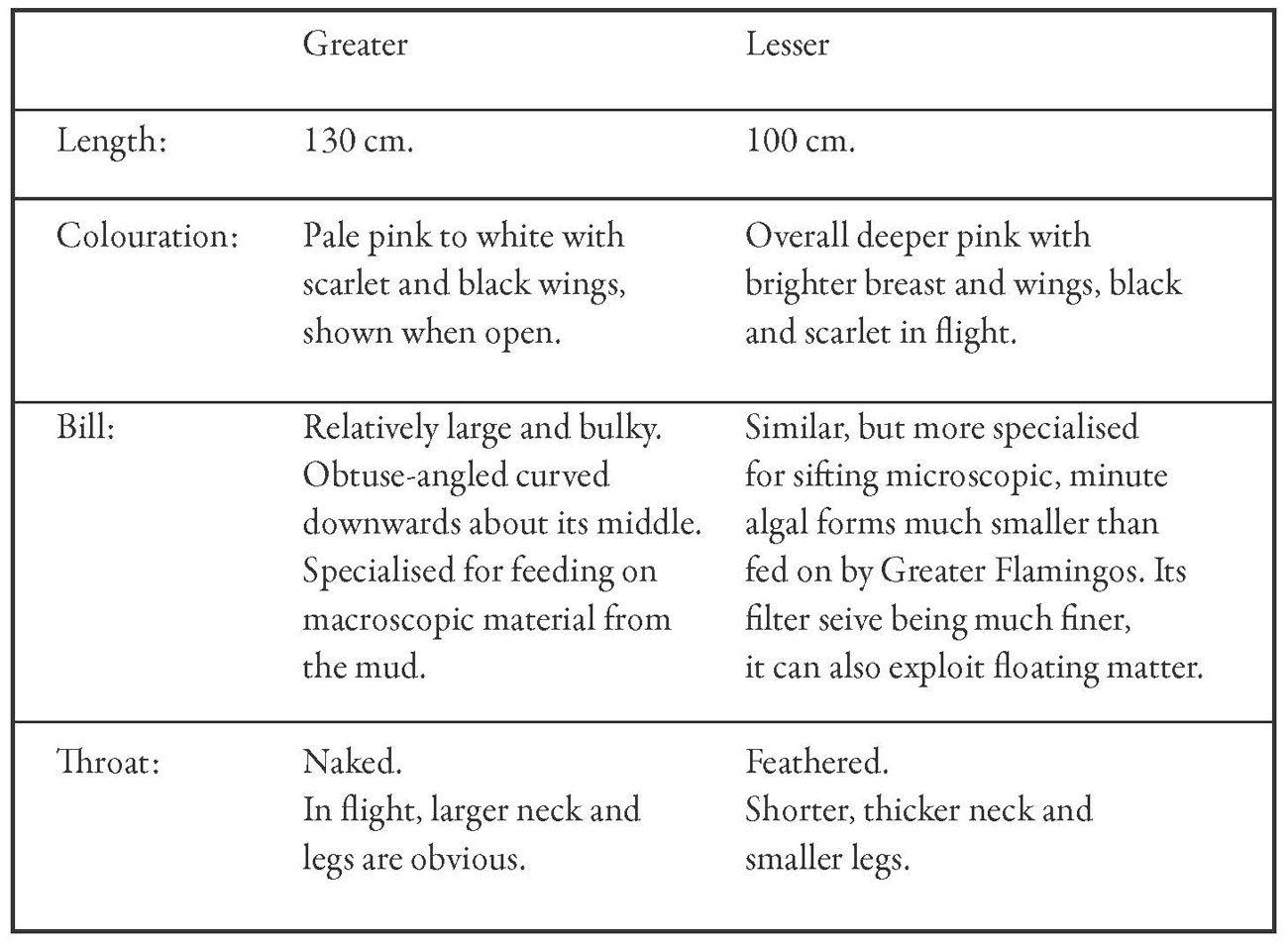

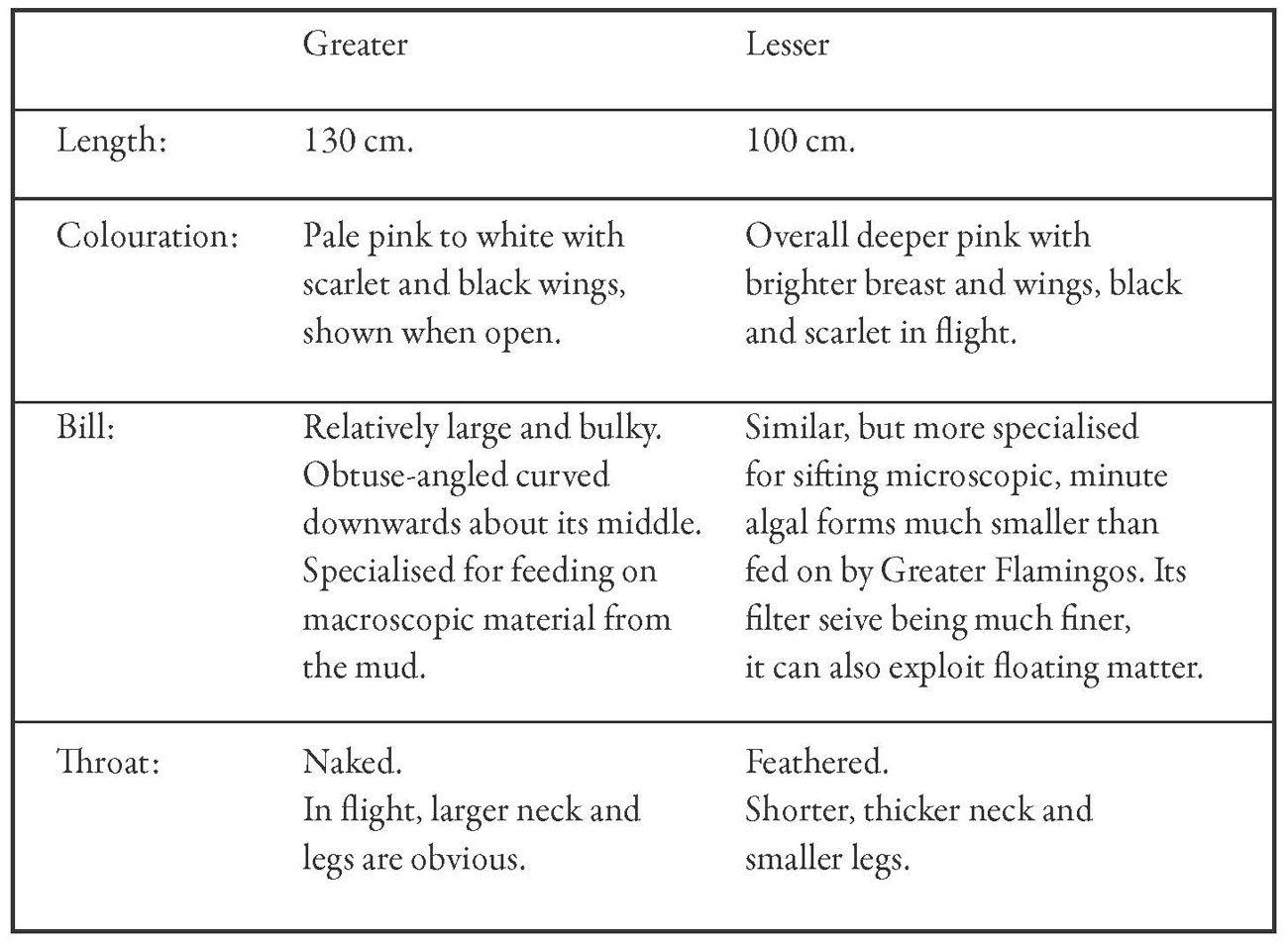

The four living species of flamingo have an irregular, patchy distribution in Southern Eurasia, Africa, Madagascar, the Caribbean and South America. Fossil finds indicate that flamingoes were once common all over Europe, North America and even Australia. Now they are to be seen only in isolated pockets, generally in the warmer tropics. The Greater Flamingo is the best known and most widespread of the flamingo family. It is a whitish bird with pink wings and is found in Kenya, along the shores of the Mediterranean, the Khirghiz steppes and in Western India and Sri Lanka. Another population of the Greater Flamingo, greatly reduced in numbers over the years, is the bright red breed, found in the West Indies and the Galapagos Islands. The third group of Greater Flamingos is the smaller, lighter-coloured Chilean Flamingo found in temperate South America, from Peru stretching down to Uruguay and Tierra del Fuego. The Lesser Flamingo, a distinct species, is found to nest in the great rift valleys of Zambia, Kenya and Tanzania. Africa has perhaps the highest density of these birds; I have watched great flocks in a tightly-packed mass, at Lake Naivasha and Nakuru in Kenya. Two other species, the Andean and the James’ are found only in the Andean highlands of South Peru, Bolivia and Chile. – Excerpt, Sanctuary Vol. VI No. 2, April/June 1986

Dr. Erach Bharucha Surgeon by profession, conservationist and teacher in environment, biodiversity and ecology by calling, he is the Director of the Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Environment Education and Research in Pune, Maharashtra.